1. Main points

UK labour productivity, as measured by output per hour, grew by 0.6% from Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) of 2016 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016. As a result, productivity on this metric has now returned to its pre-downturn level and has slightly exceeded it for the first time since 2008.

Extrapolating from performance prior to the downturn, output per hour in Quarter 2 2016 was 17.4% lower than the pre-downturn trend.

Output per hour in the services industries grew by 0.6% in Quarter 2 2016 when compared with the previous quarter and was 1.1% higher than a year earlier. Output per hour in manufacturing rose by 2.2% on the previous quarter and was 1.0% higher than a year earlier.

Output per worker was 0.2% higher and output per job was unchanged in Quarter 2 2016 compared with the previous quarter. Average hours worked fell on the quarter, resulting in higher growth in output per hour than for output per worker and output per job.

Whole economy unit labour costs were 1.2% higher in the second quarter of 2016 compared with the previous quarter and 1.9% higher than the same quarter last year, as earnings and other labour costs have outpaced productivity. Unit wage costs in manufacturing grew by 0.6% on the previous quarter and by 2.0% compared with the same quarter last year.

This edition forms part of the ONS quarterly productivity bulletin which also includes an over-arching commentary, summaries of recently published estimates and quarterly estimates of public service productivity.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Interpreting these statistics

This release reports labour productivity estimates for the second quarter (Apr to June)1 of 2016 for the whole economy and a range of sub-industries, together with selected estimates of unit labour costs. Labour productivity measures the amount of real (inflation-adjusted) economic output that is produced by a unit of labour input (measured in this release in terms of workers, jobs and hours worked) and is an important indicator of economic performance.

Labour costs make up around two-thirds of the overall cost of production of UK economic output. Unit labour costs are therefore a closely watched indicator of inflationary pressures in the economy.

Output statistics in this release are consistent with the latest Quarterly National Accounts published on 30 September 2016. Labour input measures are consistent with the latest Labour Market Statistics as described further in the “General commentary” and “Quality and methodology” sections of this bulletin.

Whole economy output (measured by gross value added – GVA) increased by 0.7% in Quarter 2 2016, while the Labour Force Survey (LFS) shows that the number of workers increased by 0.5%, while the number of jobs increased by 0.6%. Total hours worked grew more slowly, by 0.1%. This combination of movements in outputs and labour inputs implies that labour productivity across the whole economy rose by 0.6% in terms of output per hour, 0.2% in terms of output per worker, but output per job remained unchanged (subject to rounding).

Differences between the growth rates of output per worker and output per job reflect changes in the ratio of jobs to workers. This ratio increased slightly in Quarter 2 2016. Differences between these measures and output per hour reflect movements in average hours per job and per worker. Between Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2016 and Quarter 2 2016, average hours per worker fell from 32.2 to 32.0. As output per hour accounts for changes in average hours worked it is a more comprehensive indicator of labour productivity and is the main focus of the commentary in this release.

Labour productivity equation

Source: Office for National Statisitcs

Download this image Labour productivity equation

.png (11.6 kB)This equation explains how labour productivity is calculated and how it can be derived using growth rates for GVA and labour inputs.

Unit labour costs (ULCs) reflect the full labour costs, including social security and employers’ pension contributions, incurred in the production of a unit of economic output, while unit wage costs (UWCs) are a narrower measure, excluding non-wage labour costs. Growth of ULCs can be decomposed as:

Unit labour costs (ULC) equation

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Unit labour costs (ULC) equation

.png (11.8 kB)This equation explains how ULCs are calculated and how they can be derived from growth of labour costs per unit of labour (such as labour costs per hour worked) and growth of labour productivity.

In the second quarter, whole economy output per hour rose by 0.6% and ULCs grew by 1.2%. Plugging these values into the ULC equation and re-arranging yields an implied increase of approximately 1.8% in labour costs per hour. This implied movement differs from our other information on labour remuneration such as Average Weekly Earnings (AWE) and Indices of Labour Costs per Hour (ILCH), chiefly because the labour cost component includes estimated remuneration of self- employed labour, which is not included in AWE and ILCH.

Notes:

- Throughout this release, Q1 is Quarter 1 (January to March), Q2 is Quarter 2 (April to June), Q3 is Quarter 3 (July to September) and Q4 is Quarter 4 (October to December)

3. General commentary

Productivity estimates in this release are derived from estimates of the output of goods and services and of labour inputs; the latter measured in terms of workers, jobs (“Productivity Jobs”) and hours worked (“Productivity Hours”). In general, estimates of output and of labour inputs are measured independently of one another, with labour productivity calculated as the ratio of the two estimates. However, there are some activities where, in the absence of direct measures of output, labour inputs are used as a proxy, with productivity either assumed to be unchanged over time (as in public administration and defence) or assumed to move in line with the productivity trend in a measurable equivalent activity (as in a few small components of the Index of Services).

Since 2008, productivity as measured by output per hour has remained broadly flat following a long upwards trend in prior decades. Figure 1 highlights some of the drivers behind this trend, showing contributions to whole economy output per hour in terms of cumulative changes since Q1 2008. In this presentation, the contributions of individual component industries are computed, holding relative prices and industry weights constant. Allocation components are then computed for each industry, primarily as the change in relative industry shares weighted by relative productivity levels. At the aggregate level, net allocation is the sum of the individual allocation components, some negative (where relative shares are falling) and some positive. Thus a positive net allocation contribution implies a shift in shares of hours worked and/or relative prices towards higher productivity industries and vice versa.

Figure 1: Contributions to growth of whole economy output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, cumulative quarterly changes, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- ABDE refers to Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing (section A), Mining and Quarrying (section B), Electricity, Gas, Steam and Air Conditioning Supply (section D) and Water Supply, Sewerage, Waste Management and Remediation Activities (section E).

Download this chart Figure 1: Contributions to growth of whole economy output per hour

Image .csv .xlsFigure 1 shows an increasingly positive net allocation contribution over 2010 to 2012, but these unwound over 2013 to 2014, such that allocation has had a small negative impact on output per hour in the latest quarter, compared with Q1 2008. This primarily reflects changes in the relative share of industry ABDE (non-manufacturing production and agriculture). This in turn reflects changes in the nominal GVA share of ABDE in total GVA (driven by, among other factors, the price of oil and gas), together with large movements in the share of hours worked in this industry.

For the first time since the downturn, output per hour in Q2 2016 was higher than its pre-downturn peak of Q4 2007. Comparing the present position with 5 years ago, the direct contribution of non-financial services has increased and the ABDE contribution is broadly unchanged. However, the direct contributions of manufacturing, construction and financial services have weakened, as has the allocation component.

The fall in productivity growth since 2008 has been accompanied by a larger fall in labour costs per hour, resulting in a fall in the average growth of Unit Labour Costs (ULCs). ULCs are calculated with labour income as the numerator and GVA as the denominator. Labour income is total compensation of employees from the National Accounts plus an estimate of the labour income of the self-employed. The use of National Accounts income concepts means that labour costs per hour can differ from ONS estimates of Indices of Labour Costs per Hour, which relate to employees only and are not benchmarked to the National Accounts. Since labour income is around two-thirds of total GVA in current prices, sustained growth of ULCs above or below 2% could be inconsistent with delivery of the government’s inflation target. Figure 2 shows annual changes in ULCs since Q1 2008, with the bars representing the decomposition of ULC changes into changes in labour costs per hour and changes in output per hour. The latter have been reversed in sign, so a negative bar represents positive productivity growth. Estimates of labour costs per hour are backed out of estimates of unit labour costs and of output per hour.

Figure 2: Whole economy unit labour costs

Seasonally adjusted, year-on-year changes and contributions, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2000 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 2: Whole economy unit labour costs

Image .csv .xlsAverage growth of ULCs since Q1 2008 has been 1.5% per year – slightly below 2% – and down from an average of 3% in the eight years prior to Q1 2008. ULC growth has varied substantially around these averages – Figure 2 suggests that this variance is driven by both labour costs per hour as well as productivity. However, on average, growth in labour costs per hour fell by more than productivity, resulting in lower ULC growth.

Analysis of ULC growth by industry (Experimental Statistics, available in Sectional Unit Labour Costs) indicates that the trend towards lower ULC growth since the downturn is more prominent in services, while manufacturing has experienced an increase in ULCs. Between Q1 2000 and Q1 2008, average annualised ULC growth in services (3%) outpaced manufacturing (0.8%). However, since Q1 2008 this trend has reversed, with average ULC growth falling to 1.1% in services but rising to 2.1% in manufacturing. One driver of this trend is differences in productivity growth between the two, with lower productivity growth in manufacturing than services since the downturn – examined in more detail in sections 5 and 6.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Whole economy labour productivity measures

This release contains estimates for whole economy output per worker, output per job and output per hour worked, alongside estimates for market sector output per worker and output per hour worked. ONS also publish an index of market sector gross value added (GVA) as part of the Quarterly National Accounts (CDID L48H), based on weightings of industry level GVA. The main industries with sizeable non-market shares are industries L (real estate) and OPQ (government services). Estimates of market sector workers are derived by subtracting workers in central and local government from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) total. Estimates of hours worked are based on LFS microdata which record employment in a range of non-market institutions such as charities and government agencies. We are currently considering improving this methodology in line with that employed in the latest Quality Adjusted Labour Input (QALI) release, and would invite your feedback on this through our email productivity@ons.gov.uk.

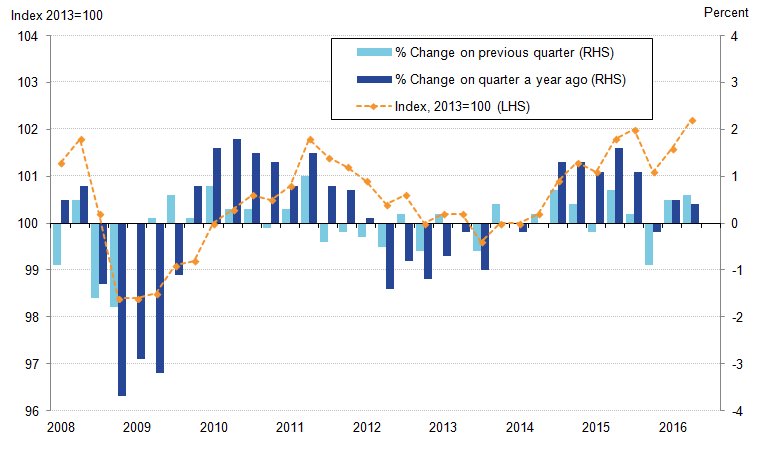

Figure 3: Whole economy output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 3: Whole economy output per hour

.png (26.5 kB) .xls (28.7 kB)As shown in Figure 3, output per hour grew by 0.6% in Q2 2016. This growth in productivity primarily reflects growth in GVA, slightly offset by a small increase in hours, as shown in Figure 4. Jobs grew by 0.7% in Q2 2016 – more strongly than hours – resulting in no change in the level of output per job compared with the previous quarter.

Figure 4: Components of productivity measures

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: Components of productivity measures

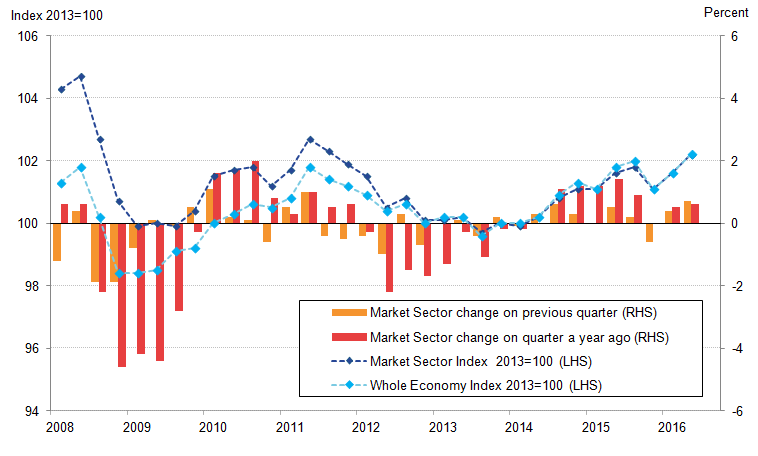

Image .csv .xlsFigure 5 shows market sector output per hour as index levels and changes alongside the equivalent index for the whole economy. Since the market sector constitutes the bulk of the economy (over 80% in terms of hours worked) the two series are closely related. However, closer investigation reveals some differences in trend growth rates pre- and post-downturn. The market sector series grew a little faster than the whole economy series in the decade prior to the pre-downturn peak of productivity (2.5% per year versus 2.2%) but has grown a little more slowly since the downturn (0.3% per year versus 0.5%).

Figure 5: Market sector output per hour worked

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 5: Market sector output per hour worked

.png (32.4 kB) .xls (29.2 kB)5. Manufacturing labour productivity measures

The weakness of manufacturing productivity since 2011 has been a defining feature of the UK productivity puzzle. As shown in Figure 6, this chiefly reflects the relative resilience of manufacturing employment and hours worked relative to manufacturing GVA. Manufacturing output fell by 12.5% between Q1 2008 and Q3 2009, considerably more than the fall in hours (10.6%) and jobs (8.3%) over the same period. During the period since the economic downturn, the recovery of output has been stronger than that of employment, although manufacturing output, jobs and hours worked have grown at similar rates since 2013.

Figure 6: Cumulative contributions to growth of manufacturing output per hour since Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- CA-CD + CM refers to Food products, beverages and tobacco (CA), Textiles, wearing apparel and leather (CB), Wood and paper products and printing (CC) and Coke and refined petroleum products (CD). CM refers to Other Manufacturing.

- CE,CF refers to Chemical and Pharmaceutical products.

- CG,CH refers to Rubber, plastics and other non-metallic minerals (CG), Basic metals and metal products (CH).

- CI-CL refers to Computer products, Electrical equipment (CI,CJ), Machinery and equipment (CK) and Transport equipment (CL).

Download this chart Figure 6: Cumulative contributions to growth of manufacturing output per hour since Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008

Image .csv .xlsIn annual terms, output per hour fell in 7 of the 10 manufacturing industries identified in the labour productivity system in 2015, including machinery and equipment (down 10.8%), rubber, plastics etc (down 9.9%), and textiles etc (down 4.1%). The only industries to record positive productivity growth in 2015 were basic metals etc (up 3.4%), chemicals and pharmaceuticals (up 2.6%) and transport equipment (up 0.8%).

More information on the labour productivity of sub-divisions of manufacturing is available in Tables 3 and 4 of this release, and in the tables at the end of the PDF version of this statistical bulletin. Care should be taken in interpreting quarter-on-quarter movements in productivity estimates for individual sub-divisions, as small sample sizes of the source data can cause volatility.

Figure 7 shows the cumulative growth of output per hour in manufacturing relative to Q1 2008, decomposed into contributions of broad component industries. In this figure the allocation element captures the effect of changes in output shares and relative prices within manufacturing.

Figure 7: Components of manufacturing productivity measures

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- CA-CD + CM refers to Food products, beverages and tobacco (CA), Textiles, wearing apparel and leather (CB), Wood and paper products and printing (CC) and Coke and refined petroleum products (CD). CM refers to Other Manufacturing

- CE,CF refers to Chemical and Pharmaceutical products

- CG,CH refers to Rubber, plastics and other non-metallic minerals (CG), Basic metals and metal products (CH)

- CI-CL refers to Computer products, Electrical equipment (CI,CJ), Machinery and equipment (CK) and Transport equipment (CL)

Download this chart Figure 7: Components of manufacturing productivity measures

Image .csv .xlsThe initial fall in manufacturing productivity during the downturn masked divergent movements among sub-industries, as the positive contribution to growth in some industries was outweighed by a fall in others. However, by Q2 2011 manufacturing productivity was 6.7% higher than in Q1 2008. While all sub-industries contributed positively to this growth, the contribution from chemical, pharmaceutical, basic metals, metal products, rubber, plastics, and other non-metallic minerals was relatively small.

From Q1 2012 manufacturing productivity fell to a trough in Q3 2013, and after picking up in 2014, once again fell during 2015. One factor behind this was the declining contribution from sub-industries CA-CD and CM. Cumulative productivity growth relative to Q1 2008 fell 5.5 percentage points between Q1 2012 and Q4 2015 – of which 3.2 percentage points can be attributed to these sub-industries. Manufacturing productivity has recovered again in the two most recent quarters, driven primarily by sub-industries CI-CL, CG and CH, but supported by most other sub-industries.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Services labour productivity measures

Labour productivity in the services industries – measured both in terms of output per hour and output per job – increased in Q2 2016 compared with the previous quarter. This increase in services labour productivity reflects output growth outpacing growth in labour inputs, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Cumulative contributions to services output per hour since Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- GHI refers to Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (G), Transportation and storage (H) and Accommodation and food service activities (I).

- J refers to Information and communication.

- K refers to Financial and insurance activities.

- L refers to Real Estate activities.

- MN refers to Professional, scientific and technical activities (M), Administrative and support service activities (N).

- MN refers to Professional, scientific and technical activities (M), Administrative and support service activities (N).

- OPQ refers to Government Services.

- RSTU refers to Other Services.

Download this chart Figure 8: Cumulative contributions to services output per hour since Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008

Image .csv .xlsFigure 9 provides a decomposition of the growth of output per hour in services since Q1 2008. Until 2013, services productivity remained broadly unchanged relative to Q1 2008. However, headline productivity over this period was pulled down by large negative contributions from government services (industries OPQ) and finance and insurance activities (K). Since 2013 the contributions from these industries have remained relatively unchanged, but increasingly positive contributions from other industries have driven growth. The distribution, accommodation and food services industries (G-I) in particular contributed 1.7 percentage points toward the increase in cumulative services productivity growth from -0.7% in Q3 2013 to 2.5% in Q2 2016. More information on labour productivity of services industries is available in Tables 5 and 6 of this release.

Figure 9: Components of services productivity measures

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 9: Components of services productivity measures

Image .csv .xlsIn general, the dispersion of labour productivity growth rates across the services industries is less pronounced than within manufacturing, but the dispersion of productivity “levels” is more pronounced. When interpreting productivity levels it should be borne in mind that labour productivity in industry L (real estate) is affected by the National Accounts concept of output from owner-occupied housing, which adds to the numerator but without a corresponding component in the denominator.

Over 2015 as a whole, output per hour grew in 8 of the 11 service industries identified in the labour productivity system, including other services (up 5.9%) and information and communication (up 5.1%). Output per hour fell in arts, entertainment, and recreation (4.3%), and accommodation and food services (1.4%).

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. What’s changed in this release?

Revisions

Compared with the previous edition published on 8 July 2016, the following are sources of revisions:

- the latest Quarterly National Accounts affect periods for GVA and unit labour costs from Q1 2015 onward

- revisions to workforce jobs affect Q1 2016 directly and periods prior to this through the impact on estimated seasonal effects

- the removal of Central Government Security from public sector employment affects estimates of market sector workers, hours, and productivity for the entirety of the series

Table A summarises differences between first published estimates for each of the statistics in the first column with the estimates for the same statistics published 3 years later. This summary is based on 5 years of data, that is, for first estimates of quarters between Quarter 3 2008 and Quarter 2 2013, which is the last quarter for which a 3-year revision history is available. The averages of these differences with and without regard to sign are shown in the right hand columns of the table. These can be compared with the estimated values in the latest quarter (Quarter 2 2016) shown in the second column. Additional information on revisions to these and other statistics published in this release is available in the dataset of this release.

Table A: Revisions analysis, relating to period: Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2013

| Whole economy | |||

| Revisions between first publication and estimates three years later (Relating to Period: 2008Q3 - 2013Q2) | |||

| Change on quarter a year ago | Value in latest period (per cent) | Average over 5 years (bias) | Average over 5 years without regard to sign (average absolute revision) |

| Output per worker | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Output per job | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Output per hour | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Unit labour costs | 1.9 | -0.2 | 1.3 |

| Unit wage costs | 1.8 | -0.6 | 1.2 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||

Download this table Table A: Revisions analysis, relating to period: Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2013

.xls (26.1 kB)This revisions analysis shows that whole economy labour productivity growth estimates have tended to be revised up very slightly over time (on a year-on-year basis). Growth of unit labour costs and unit wage costs has tended to be revised downwards. If revisions over the next three years were to be the same as the average for the past five years, growth of output per hour for the year to the second quarter of 2016 would be revised from 0.4% to 0.6%. Growth of unit labour costs would be revised from 1.9% to 1.7%, while growth of unit wage costs would be revised from 1.8% to 1.2% over the same period.

A research note, ‘Sources of revisions to labour productivity estimates’ is available on the archived version of our website.

Other developments

This statistical bulletin is published as part of a package of material relating to productivity including over-arching commentary, summaries of recent productivity-related publications and quarterly estimates of public service productivity. We welcome your views on these developments.

In addition, we would like to invite users to provide feedback on a methodological change to our measurement of labour input in the market sector in line with a QALI methodology article released alongside this bulletin.

Feedback can be sent to productivity@ons.gov.uk or by telephone to Ciaren Taylor on +44 (0)1633 455619.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Quality and methodology

This statistical bulletin presents labour productivity estimates for the UK. More detail can be found on the Productivity measures page on our website. Index numbers are referenced to 2013=100, are classified to the 2007 revision to the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) and are seasonally adjusted. Quarter on previous quarter changes in output per job and output per hour worked for some of the manufacturing sub-divisions and services sections should be interpreted with caution as the small sample sizes used can cause volatility.

The Labour productivity Quality and Methodology Information document contains important information on:

- the strengths and limitations of the data and how it compares with related data

- users and uses of the data

- how the output was created

- the quality of the output including the accuracy of the data

Notes on sources

The measure of output used in these statistics is the chained volume (real) measure of gross value added (GVA) at basic prices, with the exception of the regional analysis in Table 9, where the output measure is nominal GVA (NGVA). These measures differ because NGVA is not adjusted to account for price changes; this means that if prices were to rise more quickly in one region than the others, then this would be reflected in apparent improved measured productivity performance in that region relative to the others. At the whole economy level, real GVA is balanced to other estimates of economic activity, primarily from the expenditure approach. Below the whole economy level, real GVA is generally estimated by deflating measures of turnover; these estimates are not balanced through the supply-use framework and the deflation method is likely to produce biased estimates. This should be borne in mind in interpreting labour productivity estimates below the whole economy level.

Labour input measures used in this bulletin are known as “productivity jobs” and “productivity hours”. Productivity jobs differ from the workforce jobs (WFJ) estimates published in Table 6 of our Labour Market statistical bulletin, in 3 ways:

- to achieve consistency with the measurement of GVA, the employee component of productivity jobs is derived on a reporting unit (RU) basis, whereas the employee component of the WFJ estimates is on a local unit (LU) basis

- productivity jobs are scaled so industries sum to total Labour Force Survey (LFS) jobs – note that this constraint is applied in non-seasonally adjusted terms; the nature of the seasonal adjustment process means that the sum of seasonally adjusted productivity jobs and hours by industry can differ slightly from the seasonally adjusted LFS totals

- productivity jobs are calendar quarter average estimates whereas WFJ estimates are provided for the last month of each quarter

Productivity hours are derived by multiplying employee and self-employed jobs at an industry level (before seasonal adjustment) by average actual hours worked from the LFS at an industry level. Results are scaled so industries sum to total unadjusted LFS hours, and then seasonally adjusted.

Industry estimates of average hours derived in this process differ from published estimates (found in Table HOUR03 in the Labour Market Statistics release) as the HOUR03 estimates are calculated by allocating all hours worked to the industry of main employment, whereas the productivity hours system takes account of hours worked in first and second jobs by industry.

Whole economy unit labour costs are calculated as the ratio of total labour costs (that is, the product of labour input and costs per unit of labour) to GVA. Further detail on the methodology can be found in Revised methodology for unit wage costs and unit labour costs: explanation and impact.

Manufacturing unit wage costs are calculated as the ratio of manufacturing average weekly earnings (AWE) to manufacturing output per filled job. On 28 November 2012 we published Productivity Measures: Sectional Unit Labour Costs describing new measures of unit labour costs below the whole economy level, and proposing to replace the currently published series for manufacturing unit wage costs with a broader and more consistent measure of unit labour costs.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwysManylion cyswllt ar gyfer y Bwletin ystadegol

Related publications

- Productivity flash estimate and overview, UK: April to June 2025 and January to March 2025

- Measuring output in the Information Communication and Telecommunications industries: 2016

- Management practices and productivity in British production and services industries - initial results from the Management and Expectations Survey: 2016

- Quality adjusted labour input: UK estimates to 2016

- International comparisons of UK productivity (ICP), first estimates: 2016

- Developing labour market metrics for the market sector, UK: 2016

- Public service productivity: quarterly, UK, October to December 2019