Cynnwys

- Main points

- Things you need to know about this release

- Summary

- Net fiscal balance of London compared with other NUTS1 regions

- Largest growth in revenue in most countries and regions since financial year ending 2011

- Closer look at Air Passenger Duty and Landfill Tax

- Most countries and regions had a lower per head expenditure than the UK average

- What’s changed in this release?

- Subnational public sector finances consultation

- Links to related statistics

- Future developments

- Quality and methodology

1. Main points

London, the South East and the East of England all had net fiscal surpluses in the financial year ending (FYE) 2017, with all other countries and regions of the UK having net fiscal deficits.

London had the highest net fiscal surplus per head at £3,698 and Northern Ireland had the highest net fiscal deficit per head at £5,014, in FYE 2017.

London raised the most revenue per head, in FYE 2017, at £16,545, with Wales and the North East raising the least revenue per head at £8,371 and £8,617 respectively.

Northern Ireland and Scotland incurred the highest expenditure per head, in FYE 2017, at £13,954 and £13,237 respectively, with the lowest expenditure per head attributed to the East of England and the South East at £10,649 and £10,836 per head respectively.

Between FYE 2011 and FYE 2017, all countries and regions saw an improvement in their net fiscal balance (that is, either a decreasing deficit or increasing surplus); however, the gap between the net fiscal balances of London and the South East and those of other countries and regions has widened over this period.

2. Things you need to know about this release

What do these statistics tell me?

The aim of the country and regional public sector finances statistics is to provide users with information on what public sector expenditure has occurred, for the benefit of residents or enterprises, in each country or region of the UK and what public sector revenues have been raised in each country or region, as well as the balance between them.

“Public sector” is used in this publication to refer to central government departments and bodies (such as the Department for Work and Pensions), local authorities and other local government bodies (such as police authorities), and public sector-controlled corporations (such as Scottish Water).

Public sector revenue is the total current receipts (mainly taxes, but also social contributions, interest, dividends, gross operating surplus and transfers) received by central government and local government bodies as well as public sector-controlled corporations. It is recorded on an accrued basis, following the national accounts rules.

Public sector expenditure is the total capital and current expenditure (mainly wages and salaries, goods and services, and expenditure on fixed capital, but also subsidies, social benefits and other transfers) of central government and local government bodies as well as public sector-controlled corporations. It is recorded on an accrued basis, following the national accounts rules.

Net fiscal balance is the gap between total spending (current expenditure plus net capital expenditure) and revenue raised (current receipts), which at the UK level is equivalent to public sector net borrowing. A negative net fiscal balance figure represents a surplus, meaning that a country or region is receiving in revenue more than it is spending. A positive net fiscal balance represents a deficit, meaning a country or region is spending more than it is receiving in revenue.

The country and regional public sector finances statistics are neither reflective of the annual devolved budget settlements nor are these data used when calculating devolved budget settlements. They may not be an accurate representation of public finances should fiscal powers be fully devolved among UK countries and regions. Furthermore, they do not provide information on the spending and revenue of individual country or regional bodies such as the Greater London Authority.

The geographic boundaries used for countries and regions in the UK follows the Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics: NUTS1 definitions. Country and regional public sector finances are Experimental Statistics, but at the UK level they are consistent with the May 2018 public sector finances (PSF) bulletin, which is badged as National Statistics.

What does it mean that these are Experimental Statistics?

Experimental Statistics are statistics that are within their development phase and are published to involve potential users at an early stage in building a high-quality set of statistics that meet user needs.

This is the second time that we have published country and regional statistics on public sector revenue and expenditure. Since the first publication in May 2017, we have developed the statistics further. It should be emphasised that an Experimental Statistics label does not mean that the statistics are of low quality, it only signifies that the statistics are novel and still being developed.

Alongside this publication there is a detailed methodology guide, which sets out exactly how each revenue and expenditure item has been apportioned to countries and regions. Users should refer to this methodological information when judging whether their particular use of the statistics is appropriate.

Why are there two measures of net fiscal balance shown?

This bulletin allocates North Sea oil and gas revenues (mainly received from the Petroleum Revenue Tax and Corporation Tax) using two distinct methodologies. The first approach is to allocate the revenue on a geographic basis according to where the oilfields that give rise to the revenue are situated. The second approach to apportioning North Sea oil and gas revenue is to allocate it to all countries and regions based on their populations.

Total North Sea oil and gas revenue in the financial year ending (FYE) 2016 and FYE 2017 was close to zero, therefore the allocations of revenue between geographic and population shares are very similar in this year for all countries and regions. However, in earlier years North Sea oil and gas revenue was much more significant with a peak revenue of £10.6 billion in FYE 2009. As such, when referring to FYE 2016 or FYE 2017, net fiscal balance or total revenue including North Sea revenue on a population allocation will be quoted, unless otherwise stated.

More information on the methodology used to apportion North Sea oil and gas revenue, and all other revenues and expenditures, can be found in the methodology guide.

When will the next statistical release be published?

This is the second country and regional public sector finances publication, following the first release that we published in May 2017. We expect to publish the third release, relating to statistics for the FYE 2018, in May 2019 and the FYE 2019 statistics in late November or early December the same year.

If you would like to be kept up-to-date with next year’s release dates, please send your contact details to psa@ons.gov.uk and we will inform you of any changes.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Summary

Between the financial years ending (FYE) 2016 and 2017, the net fiscal deficit of the UK as a whole fell by £26.8 billion. All 12 Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics: NUTS1 regions saw an improvement in their net fiscal balance in the same period, meaning a decreased deficit or an increased surplus.

The greatest improvement in a net fiscal balance was seen in London, where the net fiscal surplus increased by £6.9 billion (£786 per head) between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017. The smallest change occurred in Northern Ireland, where the net fiscal deficit fell by £0.2 billion (£115 per head). This resulted in the gap between the net fiscal balance of London and the other NUTS1 regions widening, between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017.

The North West had the highest net fiscal deficit of £19.4 billion or 0.98% of gross domestic product (GDP). In contrast, London had the highest surplus of £32.6 billion or 1.63% of GDP.

The improvement in net fiscal balances was largely driven by an increase in total public sector revenue of £42.0 billion, from £684.3 billion (35.78% of GDP) in FYE 2016 to £726.3 billion (36.51% of GDP) in FYE 2017. This increase was a result of greater revenue from National Insurance contributions, Income Tax, Onshore Corporation Tax and Value Added Tax. All NUTS1 regions saw a rise in revenue between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017, but the largest increase occurred in London, at £9.4 billion, or an additional £1,083 per head.

Total expenditure of the UK increased by £15.2 billion, from £756.8 billion (39.57% of GDP) in FYE 2016 to £772.0 billion in FYE 2017 (38.81% of GDP). However, this equated to a fall of 0.76% of GDP in total expenditure, but still a slight increase in expenditure per head. This trend was seen across all NUTS1 regions.

The largest amount of expenditure in FYE 2017 occurred in London, at approximately £112.8 billion, which equates to £12,847 per head, or 14.6% of the total. However, per head expenditure in Northern Ireland was higher, at £13,954, or £26.0 billion in total.

Figure 1: Interactive map of country and regional public sector finances key aggregates

Embed code

4. Net fiscal balance of London compared with other NUTS1 regions

All of the 12 Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics: NUTS1 regions saw an improvement in their net fiscal balances between financial year ending (FYE) 2016 and FYE 2017, meaning a decreased deficit or an increased surplus. However, the improvement in London was greater than in other NUTS1 regions, resulting in the net fiscal balance gap between London and other countries and regions widening.

London’s net fiscal surplus has been increasing at a greater rate than other NUTS1 regions, since FYE 2011. Figures 2a and 2b show the average year-on-year change since FYE 2011 on both bases of calculating net fiscal balance. The average year-on-year change in London was an increase in its net fiscal surplus of almost £5.0 billion. The smallest average year-on-year change was in Scotland or Northern Ireland, depending on how North Sea revenue was allocated.

The change in net fiscal balances between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017 was largely driven by an increase in total revenue of all NUTS1 regions. However, the increase in revenue in London was larger than the increases in revenues in other NUTS1 regions. The changes in revenue are further explored in Section 5.

Figure 2a: Average year-on-year change in net fiscal balance geographic basis, since financial year ending 2011, by UK countries and English regions

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data presented from FYE 2011 as this is when current trend began.

Download this chart Figure 2a: Average year-on-year change in net fiscal balance geographic basis, since financial year ending 2011, by UK countries and English regions

Image .csv .xls

Figure 2b: Average year-on-year change in net fiscal balance population basis, since financial year ending 2011, by UK countries and English regions

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data presented from FYE 2011 as this is when current trend began.

Download this chart Figure 2b: Average year-on-year change in net fiscal balance population basis, since financial year ending 2011, by UK countries and English regions

Image .csv .xlsTable 1 shows the change in net fiscal balance of each country and region. The largest deficit decrease was in the North West, which saw a fall from £22.0 billion in FYE 2016 to £19.5 billion in FYE 2017. London saw the largest surplus increase, of £6.9 billion.

Table 1: Net fiscal balance from financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Net fiscal balance (£ million)1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Sea revenue geographic share | % of GDP2 | ||||||

| Country or region | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 10,785 | 10,429 | 9,810 | 0.58% | 0.55% | 0.49% | |

| North West | 23,440 | 22,043 | 19,409 | 1.26% | 1.15% | 0.98% | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 14,822 | 14,103 | 11,944 | 0.80% | 0.74% | 0.60% | |

| East Midlands | 9,142 | 7,738 | 6,232 | 0.49% | 0.40% | 0.31% | |

| West Midlands | 16,588 | 14,544 | 13,370 | 0.89% | 0.76% | 0.67% | |

| East of England | -682 | -2,537 | -5,495 | -0.04% | -0.13% | -0.28% | |

| London | -19,687 | -25,567 | -32,475 | -1.06% | -1.34% | -1.63% | |

| South East | -11,576 | -14,815 | -19,444 | -0.62% | -0.77% | -0.98% | |

| South West | 8,478 | 7,153 | 5,388 | 0.46% | 0.37% | 0.27% | |

| England | 51,309 | 33,090 | 8,739 | 2.77% | 1.73% | 0.44% | |

| Wales | 14,306 | 14,035 | 13,248 | 0.77% | 0.73% | 0.67% | |

| Scotland | 14,574 | 15,769 | 14,341 | 0.79% | 0.82% | 0.72% | |

| Northern Ireland | 10,300 | 9,564 | 9,348 | 0.56% | 0.50% | 0.47% | |

| UK3 | 90,490 | 72,458 | 45,677 | 4.88% | 3.79% | 2.30% | |

| North Sea revenue population share | % of GDP | ||||||

| Country or region | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 10,740 | 10,420 | 9,782 | 0.58% | 0.54% | 0.49% | |

| North West | 23,287 | 22,041 | 19,384 | 1.26% | 1.15% | 0.97% | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 14,841 | 14,047 | 11,841 | 0.80% | 0.73% | 0.60% | |

| East Midlands | 9,054 | 7,726 | 6,200 | 0.49% | 0.40% | 0.31% | |

| West Midlands | 16,438 | 14,552 | 13,367 | 0.89% | 0.76% | 0.67% | |

| East of England | -808 | -2,546 | -5,524 | -0.04% | -0.13% | -0.28% | |

| London | -19,910 | -25,556 | -32,480 | -1.07% | -1.34% | -1.63% | |

| South East | -11,803 | -14,805 | -19,454 | -0.64% | -0.77% | -0.98% | |

| South West | 8,367 | 7,146 | 5,369 | 0.45% | 0.37% | 0.27% | |

| England | 50,205 | 33,024 | 8,485 | 2.71% | 1.73% | 0.43% | |

| Wales | 14,225 | 14,040 | 13,247 | 0.77% | 0.73% | 0.67% | |

| Scotland | 15,807 | 15,828 | 14,597 | 0.85% | 0.83% | 0.73% | |

| Northern Ireland | 10,252 | 9,566 | 9,347 | 0.55% | 0.50% | 0.47% | |

| UK | 90,490 | 72,458 | 45,677 | 4.88% | 3.79% | 2.30% | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. A positive net fiscal balance indicates a deficit while a negative net fiscal balance indicates a surplus | |||||||

| 2. The GDP figures used in this publication are those published by ONS in June 2018. | |||||||

| 3. The UK figures contained in this table are equal to the Net Borrowing figures in the UK public sector finances bulletin published by ONS in June 2018. The sum of the NUTS1 regions may not be equal to the UK due to rounding. | |||||||

Download this table Table 1: Net fiscal balance from financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (45.1 kB)As the number of people in a particular country or region can affect the amount of revenue raised in that area or the amount of expenditure needed to benefit the residents and enterprises, the main aggregates in this publication are also presented on a per head basis.

Table 2 shows the net fiscal balance of the NUTS1 countries and regions from FYE 2015 to the FYE 2017. Northern Ireland had the highest net fiscal deficit, while London had the highest net fiscal surplus, in FYE 2017.

Table 2: Net fiscal balance per head from financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Net Fiscal Balance per head (£)1, 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Sea revenue geographic share | North Sea revenue population share | ||||||

| Country or region | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 4,116 | 3,969 | 3,718 | 4,099 | 3,966 | 3,707 | |

| North West | 3,281 | 3,067 | 2,684 | 3,260 | 3,067 | 2,680 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 2,761 | 2,612 | 2,199 | 2,765 | 2,602 | 2,180 | |

| East Midlands | 1,967 | 1,650 | 1,316 | 1,948 | 1,648 | 1,309 | |

| West Midlands | 2,898 | 2,521 | 2,296 | 2,872 | 2,522 | 2,295 | |

| East of England | -113 | -417 | -895 | -134 | -418 | -900 | |

| London | -2,297 | -2,941 | -3,697 | -2,323 | -2,940 | -3,698 | |

| South East | -1,302 | -1,652 | -2,150 | -1,327 | -1,651 | -2,151 | |

| South West | 1,560 | 1,305 | 975 | 1,539 | 1,303 | 971 | |

| England | 943 | 603 | 158 | 922 | 601 | 153 | |

| Wales | 4,624 | 4,524 | 4,251 | 4,598 | 4,525 | 4,251 | |

| Scotland | 2,722 | 2,931 | 2,651 | 2,952 | 2,942 | 2,698 | |

| Northern Ireland | 5,588 | 5,158 | 5,014 | 5,562 | 5,159 | 5,014 | |

| UK3 | 1,398 | 1,111 | 695 | 1,398 | 1,111 | 695 | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. A positive net fiscal balance indicates a deficit while a negative net fiscal balance indicates a surplus. | |||||||

| 2. The population estimates used in this publication are those published by ONS. | |||||||

| 3. The UK figures contained in this table are equal to the net borrowing figures in the UK public sector finances bulletin published by ONS in June 2018. The sum of the NUTS1 regions may not be equal to the UK due to rounding. | |||||||

Download this table Table 2: Net fiscal balance per head from financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (42.5 kB)The UK as a whole has had a net fiscal deficit since FYE 2003. However, this varies between countries and regions. Most countries and regions have had a net fiscal deficit for the full duration of the period presented in these statistics, which is since FYE 2000. Some regions, such as the East of England, East Midlands and the South West had net fiscal surpluses in the early period, while London and the South East have generally maintained net fiscal surpluses for the full period.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Largest growth in revenue in most countries and regions since financial year ending 2011

Between the financial years ending (FYE) 2016 and 2017, total public sector revenue raised in the UK grew by £42.0 billion, or 0.73% of gross domestic product (GDP). This is the largest increase in total revenue since FYE 2011, where total revenue increased by £35.9 billion, or 1.10% of GDP. Each of the 12 Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics: NUTS1 regions have seen an increase in revenue since FYE 2011.

Of this £42.0 billion increase in revenue, £9.4 billion was raised in London. The smallest increase was in Northern Ireland, at £0.7 billion. These increases corresponded to an additional £1,083 per head in London and £378 in Northern Ireland.

Figure 3 shows how much each NUTS1 region contributed to the overall revenue increase in the UK, in FYE 2017.

Figure 3: Contribution of NUTS1 regions to overall UK revenue increase in financial year ending 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 3: Contribution of NUTS1 regions to overall UK revenue increase in financial year ending 2017

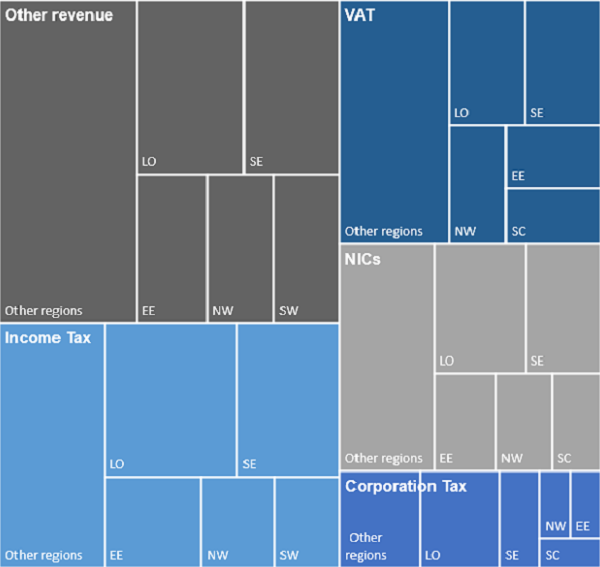

Image .csv .xlsThe increase in revenue in all NUTS1 regions, and therefore the UK, was mainly driven by growth in National Insurance contributions (NICs), Onshore Corporation Tax, Income Tax and Value Added Tax (VAT).

NICs increased by £12.0 billion between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017, equating to 0.6% of GDP, which compares with an average annual growth of 0.18% of GDP in the preceding five years. Income Tax increased by £8.5 billion between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017, equating to 0.42% of GDP. However, this was similar to the growth between FYE 2015 and FYE 2014. Given the similarities in the tax base, revenue from NICs and Income Tax have followed a similar trend for the full duration presented in these statistics. However, it is not common for NICs growth as a percentage of GDP, to outstrip that of Income Tax. This unusual boost to NICs was partly a result of removing the NICs contracting out rebate, from April 2016.

London (£68.7 billion), the South East (£53.9 billion), the East of England (£31.7 billion), the North West (£25.8 billion) and Scotland (£22.4 billion) are the top five regions where most Income Tax and NICs are generally raised; together they accounted for 68% and 63% of the totals in FYE 2017, respectively. However, the NUTS1 regions that raised the highest per head amount of Income Tax and NICs in FYE 2017 were London (£7,822), the South East (£5,963), the East of England (£5,172), Scotland (£4,145) and the East Midlands (£3,728).

Many factors influence the amount of Income Tax and NICs raised, such as the level of pay and the number of people employed. Country and regional breakdowns of these factors are available from our Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) and Annual Population Survey.

Table 3 shows the median annual gross pay and employment levels for each region, in the year 2017. The gross pay estimates are for all employees aged 16 or over, whereas the employment levels include all employees and the self-employed. Both estimates are produced based on the residential location of individuals as are estimates in the country and regional public sector finances.

London, the South West, the East of England, the North West and Scotland feature in the top five or six regions in terms of median annual gross earnings (for full-time and part-time employees) and the number of people employed in each region. This in part explains some of the regional variation in Income Tax and NICs raised. The median annual gross pay in Scotland is higher than in the North West, however, there are more people in employment in the North West, suggesting this is one reason why more Income Tax and NICs are raised in the North West than in Scotland.

Table 3: Median gross annual pay and employment levels, 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Country or region | Median annual gross pay1,2, 2017 (£) | Employment level3 Jan 2017 to Mar 2017 (no. of people) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| North East | 21,822 | 1,219,000 | |

| North West | 21,960 | 3,445,000 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 21,419 | 2,576,000 | |

| East Midlands | 21,938 | 2,280,000 | |

| West Midlands | 22,259 | 2,641,000 | |

| East | 24,602 | 3,029,000 | |

| London | 29,666 | 4,568,000 | |

| South East | 25,780 | 4,536,000 | |

| South West | 22,074 | 2,749,000 | |

| England | 23,743 | 27,043,000 | |

| Wales | 21,500 | 1,460,000 | |

| Scotland | 23,154 | 2,620,000 | |

| Northern Ireland | 21,326 | 824,000 | |

| United Kingdom | 23,474 | 31,947,000 | |

| Sources: Office for National Statistics | |||

| Notes: | |||

| 1. Median annual gross pay estimates are from Table 8.7a of the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings publication. Estimates for 2017 are provisional and will be revised. | |||

| 2. Median annual gross pay for all employees (full-time and part-time) and employment levels are both residence-based estimates. | |||

| 3. Employment levels are for all those aged 16 and over (including those that are self-employed). Estimates are on a residential basis and from the Annual Population Survey. | |||

Download this table Table 3: Median gross annual pay and employment levels, 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (29.2 kB)Between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017, revenue from Onshore Corporation Tax and VAT increased by £8.4 billion and £4.8 billion, respectively. Of the £53.7 billion of Onshore Corporation Tax, 45% of this was raised in London (£16.4 billion) and the South East (£8.2 billion). This corresponded to £1,869 per head in London and £902 per head in the South East. Onshore Corporation Tax is attributed to NUTS1 regions based on the registered location of a company.

The revenue raised from VAT is more evenly distributed across the NUTS1 regions. For the full duration of the statistics in this bulletin, approximately 15% of the total was raised in London and a further 15% in the South East, owing to households paying the most VAT (approximately 70%). This also means that the distribution of VAT across NUTS1 regions is relatively in line with population distributions.

Revenue from VAT has steadily increased from FYE 2011; factors that contribute to these increases include, but are not limited to, tax policy changes, household spending patterns or prices. The underlying data used to allocate VAT paid by households to NUTS1 regions are from the Living Costs and Food Survey, which has shown that household consumption has increased since 2010.

Figure 4 shows the largest components of total revenue in FYE 2017, by the regions in which the largest amounts were raised.

Figure 4: Total revenue in financial year ending (FYE) 2017, by largest component, UK countries and English regions

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 4: Total revenue in financial year ending (FYE) 2017, by largest component, UK countries and English regions

.png (51.6 kB) .xlsx (17.3 kB)Over time, the revenue of most countries and regions as a percentage of GDP has been fairly stable. At the UK level, it has remained between 33% and 37% of GDP for the full duration presented in these statistics. Table 4 shows revenue raised in each country and region over the last five years, as a percentage of GDP. Over this five-year period, total revenue has grown by 0.79% of GDP, of which 0.64% of GDP occurred in London.

Table 4: Total public sector revenue as a percentage of UK gross domestic product Financial year ending (FYE) 2013 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Total public sector revenue as % of GDP1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Sea revenue geographic share | |||||

| Country or region | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 |

| North East | 1.18% | 1.16% | 1.13% | 1.13% | 1.14% |

| North West | 3.29% | 3.26% | 3.23% | 3.26% | 3.32% |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 2.50% | 2.47% | 2.45% | 2.44% | 2.48% |

| East Midlands | 2.23% | 2.22% | 2.22% | 2.24% | 2.27% |

| West Midlands | 2.60% | 2.58% | 2.57% | 2.59% | 2.63% |

| East of England | 3.44% | 3.46% | 3.47% | 3.51% | 3.56% |

| London | 6.66% | 6.84% | 6.93% | 7.11% | 7.31% |

| South East | 5.67% | 5.68% | 5.69% | 5.74% | 5.90% |

| South West | 2.81% | 2.81% | 2.81% | 2.82% | 2.87% |

| England | 30.39% | 30.48% | 30.50% | 30.83% | 31.49% |

| Wales | 1.31% | 1.30% | 1.30% | 1.29% | 1.31% |

| Scotland | 3.14% | 3.06% | 2.94% | 2.83% | 2.88% |

| Northern Ireland | 0.88% | 0.84% | 0.84% | 0.83% | 0.84% |

| UK | 35.72% | 35.68% | 35.58% | 35.78% | 36.51% |

| North Sea revenue population share | |||||

| Country or region | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 |

| North East | 1.19% | 1.16% | 1.14% | 1.13% | 1.14% |

| North West | 3.32% | 3.28% | 3.24% | 3.26% | 3.32% |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 2.49% | 2.47% | 2.45% | 2.44% | 2.49% |

| East Midlands | 2.24% | 2.23% | 2.22% | 2.24% | 2.28% |

| West Midlands | 2.63% | 2.60% | 2.58% | 2.58% | 2.63% |

| East of England | 3.47% | 3.47% | 3.47% | 3.51% | 3.56% |

| London | 6.71% | 6.87% | 6.94% | 7.11% | 7.31% |

| South East | 5.72% | 5.72% | 5.70% | 5.74% | 5.90% |

| South West | 2.83% | 2.83% | 2.82% | 2.82% | 2.87% |

| England | 30.60% | 30.63% | 30.56% | 30.83% | 31.50% |

| Wales | 1.33% | 1.31% | 1.30% | 1.29% | 1.31% |

| Scotland | 2.90% | 2.89% | 2.87% | 2.82% | 2.87% |

| Northern Ireland | 0.89% | 0.85% | 0.84% | 0.83% | 0.84% |

| UK | 35.72% | 35.68% | 35.58% | 35.78% | 36.51% |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Note: | |||||

| 1. The GDP figures used in this publication are those published by ONS in June. | |||||

Download this table Table 4: Total public sector revenue as a percentage of UK gross domestic product Financial year ending (FYE) 2013 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (43.5 kB)Table 5 shows how much revenue was estimated to be raised in each country and region, both in total and per head, from FYE 2015 to FYE 2017.

Table 5: Total public sector revenue financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Total public sector revenue | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Sea revenue geographic share (£ million) | Per head (£)1 | ||||||

| Country or region | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 21,017 | 21,614 | 22,738 | 8,021 | 8,226 | 8,617 | |

| North West | 60,006 | 62,342 | 65,975 | 8,400 | 8,674 | 9,122 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 45,466 | 46,670 | 49,400 | 8,470 | 8,644 | 9,095 | |

| East Midlands | 41,115 | 42,813 | 45,238 | 8,847 | 9,130 | 9,550 | |

| West Midlands | 47,704 | 49,438 | 52,247 | 8,334 | 8,570 | 8,972 | |

| East of England | 64,317 | 67,089 | 70,866 | 10,663 | 11,018 | 11,544 | |

| London | 128,548 | 135,922 | 145,317 | 14,998 | 15,636 | 16,544 | |

| South East | 105,486 | 109,747 | 117,437 | 11,862 | 12,235 | 12,987 | |

| South West | 52,154 | 53,918 | 57,071 | 9,595 | 9,834 | 10,325 | |

| England | 565,813 | 589,553 | 626,289 | 10,394 | 10,737 | 11,314 | |

| Wales | 24,041 | 24,716 | 26,086 | 7,771 | 7,966 | 8,371 | |

| Scotland | 54,516 | 54,078 | 57,267 | 10,182 | 10,050 | 10,586 | |

| Northern Ireland | 15,585 | 15,962 | 16,667 | 8,455 | 8,608 | 8,940 | |

| UK2 | 659,955 | 684,309 | 726,309 | 10,196 | 10,488 | 11,047 | |

| North Sea revenue population share | Per head1 | ||||||

| Country or region | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 21,062 | 21,623 | 22,766 | 8,038 | 8,229 | 8,628 | |

| North West | 60,159 | 62,344 | 66,000 | 8,421 | 8,674 | 9,125 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 45,447 | 46,726 | 49,503 | 8,467 | 8,655 | 9,114 | |

| East Midlands | 41,203 | 42,825 | 45,270 | 8,866 | 9,132 | 9,557 | |

| West Midlands | 47,854 | 49,430 | 52,250 | 8,360 | 8,568 | 8,973 | |

| East of England | 64,443 | 67,098 | 70,895 | 10,684 | 11,019 | 11,549 | |

| London | 128,771 | 135,911 | 145,322 | 15,024 | 15,635 | 16,545 | |

| South East | 105,713 | 109,737 | 117,447 | 11,887 | 12,234 | 12,988 | |

| South West | 52,265 | 53,925 | 57,090 | 9,616 | 9,835 | 10,328 | |

| England | 566,917 | 589,619 | 626,543 | 10,415 | 10,739 | 11,318 | |

| Wales | 24,122 | 24,711 | 26,087 | 7,797 | 7,965 | 8,372 | |

| Scotland | 53,283 | 54,019 | 57,011 | 9,952 | 10,039 | 10,539 | |

| Northern Ireland | 15,633 | 15,960 | 16,668 | 8,481 | 8,607 | 8,941 | |

| UK | 659,955 | 684,309 | 726,309 | 10,196 | 10,488 | 11,047 | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. The population estimates used in this publication are those published by ONS | |||||||

| 2. The UK figures contained in this table are equal to the figures in the UK public sector finances bulletin published by ONS in June 2018. The sum of the NUTS1 regions may not be equal to the United Kingdom due to rounding. | |||||||

Download this table Table 5: Total public sector revenue financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (44.5 kB)6. Closer look at Air Passenger Duty and Landfill Tax

This year we improved the way in which we allocate Air Passenger Duty and Landfill Tax to the countries and regions of the UK; these improvements better reflect the regional differences and different tax rates. Further information is available in the methodology guide.

Air Passenger Duty

Air Passenger Duty (APD) is paid by aircraft operators carrying passengers departing from a UK airport. The amount of APD due per passenger depends on the final destination and class of travel; higher APD is due on longer distance flights or higher classes of travel. As such, the amount of APD raised in each region depends on the airports located in that region and the type of flights operated from those airports.

In the financial year ending (FYE) 2017, revenue from APD for the whole of the UK was £3.2 billion. Almost 50% (£1.6 billion) of this was raised from airports located in London (Heathrow, Gatwick, London City, Luton and Biggin Hill). According to the Civil Aviation Authority’s (CAA) departing passenger survey reports, Heathrow and Gatwick airports receive the most passenger traffic; in 2017 over 50%1 of all departing passengers travelled through these two airports.

The greater proportion of APD raised in London can therefore be attributed primarily to passenger numbers. The composition of international and domestic passengers also affects the amount of APD raised as international flights attract higher rates. The CAA’s departing passenger survey reports from 2017, 2016 and 2015 show that most airports located in England2 have more international passengers than domestic, while airports located outside England tend to either have fairly even numbers of international and domestic passengers or greater domestic passengers.

Figure 5: Air Passenger Duty, financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 5: Air Passenger Duty, financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

Image .csv .xlsLandfill Tax

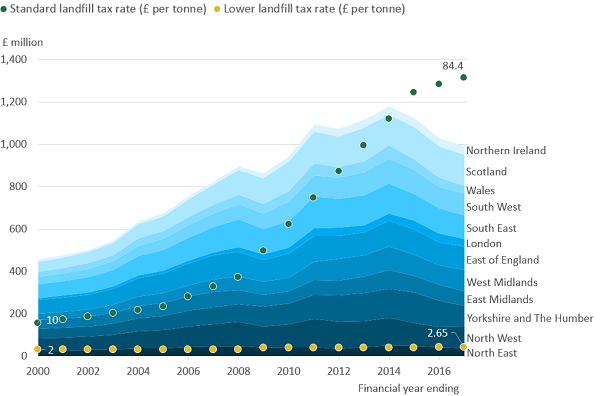

Landfill Tax is an environmental tax paid by landfill site operators on waste disposed at landfill sites. Waste disposed of at landfill sites includes inert waste, such as rocks or soil; hazardous waste, which could be toxic, explosive or other similar criteria; and non-hazardous waste. Different rates apply to each category of waste.

Landfill Tax was devolved to Scotland in April 2015 and is known as Scottish Landfill Tax (SLfT). As such, from FYE 2016 onwards, outturn data from Revenue Scotland are used in this publication. Since April 2018, Landfill Tax has been devolved to Wales and is known as Landfill Disposals Tax (LDT). Data for Wales, in this publication, will continue to be estimated until outturn data can be used from FYE 2019.

For FYE 2017, revenue from Landfill Tax for the whole of the UK was £0.9 billion. The region in which most Landfill Tax was raised was Scotland and this has been the case since FYE 2009. Prior to this, the South East was the region in which most Landfill Tax was raised. In FYE 2017, £0.15 million Landfill Tax was raised in Scotland, which accounts for 15% of the total.

The amount of Landfill Tax raised in a region is driven by the amount of waste landfilled as well as whether the waste attracts the standard rate, lower rate or is exempt from Landfill Tax. In FYE 2017, landfill sites in the East of England3 received the most waste, whereas Scotland4 ranked fifth. Based on our methodology, the difference between the two regions is that more standard-rated waste is landfilled in Scotland than in the East of England (and other regions), and as such, Landfill Tax raised in Scotland is greater than the rest of the UK.

Although revenue raised from Landfill Tax has increased over the last two decades, there has been a steady decline in waste sent to landfill sites across most regions; reflecting perhaps alternative waste treatment processes and more recycling. Therefore, the growth in Landfill Tax revenue can be attributed to increasing tax rates.

Figure 6: Landfill Tax revenue and rates, financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Landfill Tax has been devolved in Scotland since financial year ending (FYE) 2016, therefore actual revenue data for Scotland are used.

- Scottish Landfill Tax rates in FYE 2016 and FYE 2017 match those in the rest of the UK.

Download this image Figure 6: Landfill Tax revenue and rates, financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.png (84.1 kB) .xlsx (22.2 kB)Notes for: Closer look at Air Passenger Duty and Landfill Tax

For more information, see Table 1 of CAA Passenger Survey Report 2017.

Heathrow airport is a slight exception as it has the largest percentage of connecting passengers, at 30%, compared with 1% to 5% in other airports.

Data for England on waste sent to landfill sites are published by the Environment Agency.

Data for Scotland are provided by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency.

7. Most countries and regions had a lower per head expenditure than the UK average

In the financial year ending (FYE) 2017, total public sector expenditure at the UK level was £772.0 billion, or £11,742 per head. The Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics: NUTS1 region incurring the most expenditure for the benefit of residents and enterprises was London, at approximately £112.7 billion, which equates to £12,847 per head, or approximately 15% of the UK total.

On average, for the full duration of the statistics presented in this publication, spending per head each year, in Northern Ireland; Scotland; Wales; London; the North West; and the North East has been above the UK average. Figure 7 shows how much each NUTS1 region has spent per head, compared with the UK on average, between FYE 2000 and FYE 2017.

Figure 7: Average NUTS1 per head spending differences against UK per head over financial year ending 2000 to financial year ending 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 7: Average NUTS1 per head spending differences against UK per head over financial year ending 2000 to financial year ending 2017

Image .csv .xlsTable 6 shows how much of this expenditure occurred for the benefit of residents and enterprises in each country and region in the UK from FYE 2015 to FYE 2017.

Table 6: Total public sector expenditure from financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Total public sector expenditure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total public sector expenditure (£ million) | Per head (£)1 | ||||||

| Country or region | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 31,802 | 32,043 | 32,548 | 12,137 | 12,195 | 12,335 | |

| North West | 83,446 | 84,385 | 85,384 | 11,681 | 11,741 | 11,805 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 60,288 | 60,773 | 61,344 | 11,232 | 11,256 | 11,294 | |

| East Midlands | 50,257 | 50,551 | 51,470 | 10,814 | 10,780 | 10,866 | |

| West Midlands | 64,292 | 63,982 | 65,617 | 11,232 | 11,091 | 11,268 | |

| East of England | 63,635 | 64,552 | 65,371 | 10,550 | 10,601 | 10,649 | |

| London | 108,861 | 110,355 | 112,842 | 12,701 | 12,695 | 12,847 | |

| South East | 93,910 | 94,932 | 97,993 | 10,560 | 10,584 | 10,836 | |

| South West | 60,632 | 61,071 | 62,459 | 11,155 | 11,138 | 11,300 | |

| England | 617,122 | 622,643 | 635,028 | 11,337 | 11,340 | 11,472 | |

| Wales | 38,347 | 38,751 | 39,334 | 12,395 | 12,490 | 12,623 | |

| Scotland | 69,090 | 69,848 | 71,609 | 12,904 | 12,981 | 13,237 | |

| Northern Ireland | 25,885 | 25,526 | 26,015 | 14,043 | 13,766 | 13,954 | |

| UK2 | 750,445 | 756,767 | 771,986 | 11,594 | 11,599 | 11,742 | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. The population estimates used in this publication are those published by ONS. | |||||||

| 2. The United Kingdom figures contained in this table are equal to the figures in the UK public sector finances bulletin published by ONS in June 2018. The sum of the NUTS1 regions may not be equal to the United Kingdom due to rounding. | |||||||

Download this table Table 6: Total public sector expenditure from financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (42.5 kB)Between FYE 2016 and FYE 2017, total expenditure increased from £756.8 billion to £772.0 billion, however, this equated to a fall of 0.76% of gross domestic product (GDP). Between FYE 2011 and FYE 2017, total UK public sector expenditure has fallen by 5.84% of GDP. While London has seen the largest drop in expenditure of 0.84% of GDP, all other NUTS1 regions have seen a fall in expenditure between 0.20% and 0.77% of GDP. As such, the expenditure gap between London and other NUTS1 regions is not as wide compared with revenue raised.

Table 7: Total public sector expenditure as a percentage of UK gross domestic product Financial year ending (FYE) 2011 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Total public sector expenditure as % of GDP1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country or region | 2010/11 | 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 |

| North East | 1.94% | 1.88% | 1.84% | 1.77% | 1.71% | 1.68% | 1.64% |

| North West | 5.06% | 4.89% | 4.82% | 4.58% | 4.50% | 4.41% | 4.29% |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 3.61% | 3.53% | 3.47% | 3.32% | 3.25% | 3.18% | 3.08% |

| East Midlands | 2.95% | 2.87% | 2.84% | 2.74% | 2.71% | 2.64% | 2.59% |

| West Midlands | 3.80% | 3.71% | 3.65% | 3.50% | 3.47% | 3.35% | 3.30% |

| East of England | 3.78% | 3.63% | 3.58% | 3.46% | 3.43% | 3.38% | 3.29% |

| London | 6.52% | 6.34% | 6.20% | 5.98% | 5.87% | 5.77% | 5.67% |

| South East | 5.53% | 5.32% | 5.30% | 5.16% | 5.06% | 4.96% | 4.93% |

| South West | 3.53% | 3.45% | 3.40% | 3.31% | 3.27% | 3.19% | 3.14% |

| England | 36.71% | 35.62% | 35.10% | 33.83% | 33.27% | 32.56% | 31.92% |

| Wales | 2.30% | 2.28% | 2.20% | 2.12% | 2.07% | 2.03% | 1.98% |

| Scotland | 4.13% | 4.07% | 4.01% | 3.83% | 3.72% | 3.65% | 3.60% |

| Northern Ireland | 1.51% | 1.49% | 1.48% | 1.42% | 1.40% | 1.33% | 1.31% |

| UK | 44.65% | 43.46% | 42.78% | 41.19% | 40.45% | 39.57% | 38.81% |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Note: | |||||||

| 1. The GDP figures used in this publication are those published by ONS in June 2018. | |||||||

Download this table Table 7: Total public sector expenditure as a percentage of UK gross domestic product Financial year ending (FYE) 2011 to FYE 2017, by UK countries and English regions

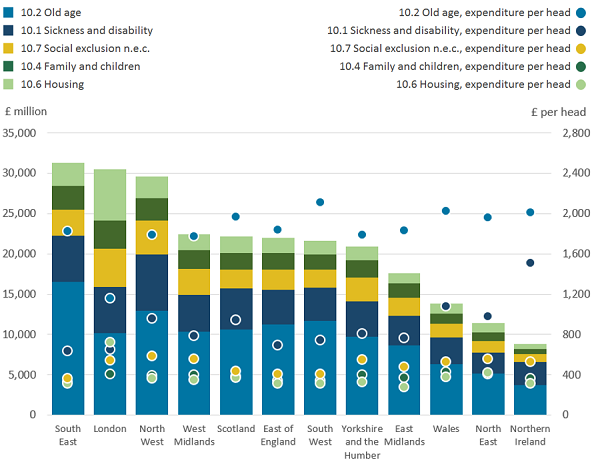

.xls (42.0 kB)For all regions, social protection is the largest category of spending, followed by health and education. The underlying expenditure data used in this publication is from HM Treasury’s (HMT) Country and regional analysis, with some adjustments. Expenditure data in this publication are at the Classifications of Functions of Government: COFOG level 0, whereas HMT break this down further in their publication. COFOG level 1 data from HMT’s country and regional analysis publication show that spending on old age makes up the largest component of social protection spending. Figure 8 shows spending in the largest four sub-functions, across each NUTS1 region, as well as per head figures.

Spending in a country is influenced by a variety of factors, such as the demographics of a region and therefore the different needs of residents; the type of infrastructure; industry; or prices. For example, old age spending is highest in the South East, which is consistent with the region having the largest aged 65 years and over population in the country1.

Figure 8: Spending in largest social protection sub-functions, financial year ending (FYE) 2017, by UK countries and English regions

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Identifiable expenditure data on social protection sub-functions obtained from HM Treasury's Country and regional analysis: 2017 publication.

- HM Treasury's sub-functions are based on Classifications of Functions of Government (COFOG) level 1 categories.

Download this image Figure 8: Spending in largest social protection sub-functions, financial year ending (FYE) 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.png (92.8 kB) .xlsx (20.6 kB)

Table 8: Total public sector expenditure for financial year ending (FYE) 2017, by UK countries and English regions

| Total expenditure (£ million) | North East | North West | Yorkshire and The Humber | East Midlands | West Midlands | East of England | London |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. General public services | 2,445 | 6,606 | 4,956 | 4,398 | 5,357 | 5,801 | 8,389 |

| 1. of which: public and common services | 439 | 1,108 | 827 | 798 | 931 | 1,135 | 1,713 |

| 1. of which: international services | 394 | 1,081 | 812 | 708 | 870 | 917 | 1,312 |

| 1. of which: public sector debt interest | 1,611 | 4,417 | 3,317 | 2,893 | 3,556 | 3,749 | 5,364 |

| 2. Defence | 1,484 | 4,072 | 3,056 | 2,667 | 3,277 | 3,456 | 4,943 |

| 3. Public order and safety | 1,355 | 3,433 | 2,374 | 1,953 | 2,486 | 2,315 | 5,553 |

| 4. Economic affairs | 1,525 | 4,301 | 3,177 | 2,312 | 3,194 | 3,532 | 10,248 |

| 4. of which: enterprise and economic development | 215 | 550 | 368 | 410 | 439 | 400 | 826 |

| 4. of which: science and technology | 153 | 380 | 277 | 276 | 298 | 431 | 573 |

| 4. of which: employment policies | 166 | 276 | 264 | 166 | 272 | 153 | 354 |

| 4. of which: agriculture, fisheries and forestry | 205 | 370 | 411 | 386 | 318 | 455 | 84 |

| 4. of which: transport | 786 | 2,725 | 1,857 | 1,075 | 1,867 | 2,092 | 8,411 |

| 5. Environment protection | 336 | 2,325 | 677 | 515 | 676 | 893 | 1,153 |

| 6. Housing and community amenities | 484 | 790 | 753 | 601 | 811 | 678 | 1,793 |

| 7. Health | 6,257 | 16,837 | 11,541 | 9,211 | 12,835 | 11,562 | 23,596 |

| 8. Recreation, culture and religion | 465 | 1,179 | 914 | 715 | 865 | 856 | 1,829 |

| 9. Education (includes training) | 3,355 | 9,216 | 6,943 | 5,879 | 7,462 | 7,761 | 14,104 |

| 10. Social protection | 12,034 | 30,876 | 22,089 | 18,446 | 23,657 | 22,955 | 32,048 |

| EU transactions | 87 | 547 | 239 | 156 | 369 | 351 | 2,227 |

| Accounting Adjustments2 | 2,722 | 5,202 | 4,626 | 4,616 | 4,631 | 5,212 | 6,959 |

| Total | 32,548 | 85,384 | 61,344 | 51,470 | 65,617 | 65,371 | 112,842 |

| Total expenditure (£ million) | South East | South West | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | UK |

| 1. General public services | 8,948 | 5,197 | 52,098 | 3,113 | 5,604 | 1,906 | 62,722 |

| 1. of which: public and common services | 2,074 | 996 | 10,022 | 745 | 1,493 | 489 | 12,748 |

| 1. of which: international services | 1,351 | 826 | 8,271 | 466 | 808 | 279 | 9,823 |

| 1. of which: public sector debt interest | 5,522 | 3,376 | 33,805 | 1,903 | 3,304 | 1,139 | 40,150 |

| 2. Defence | 5,090 | 3,110 | 31,154 | 1,754 | 3,044 | 1,048 | 36,999 |

| 3. Public order and safety | 3,235 | 2,028 | 24,731 | 1,343 | 2,729 | 1,270 | 30,073 |

| 4. Economic affairs | 5,806 | 3,250 | 37,345 | 2,371 | 6,044 | 1,620 | 47,381 |

| 4. of which: enterprise and economic development | 1,138 | 414 | 4,761 | 415 | 990 | 352 | 6,518 |

| 4. of which: science and technology | 604 | 349 | 3,340 | 159 | 395 | 77 | 3,971 |

| 4. of which: employment policies | 204 | 125 | 1,979 | 136 | 243 | 100 | 2,458 |

| 4. of which: agriculture, fisheries and forestry | 438 | 636 | 3,303 | 467 | 1,020 | 507 | 5,298 |

| 4. of which: transport | 3,422 | 1,726 | 23,962 | 1,194 | 3,396 | 584 | 29,136 |

| 5. Environment protection | 1,276 | 1,008 | 8,859 | 640 | 1,376 | 267 | 11,142 |

| 6. Housing and community amenities | 868 | 430 | 7,206 | 715 | 1,767 | 766 | 10,454 |

| 7. Health | 17,539 | 11,123 | 120,499 | 6,988 | 12,666 | 4,192 | 144,345 |

| 8. Recreation, culture and religion | 1,373 | 799 | 8,995 | 674 | 1,392 | 587 | 11,649 |

| 9. Education (includes training) | 10,879 | 6,564 | 72,163 | 4,186 | 8,173 | 2,717 | 87,239 |

| 10. Social protection | 32,662 | 22,483 | 217,249 | 14,560 | 23,415 | 9,167 | 264,391 |

| EU transactions | 1,009 | 115 | 5,100 | -127 | -32 | -218 | 4,723 |

| Accounting Adjustments2 | 9,309 | 6,352 | 49,629 | 3,117 | 5,430 | 2,693 | 60,869 |

| Total | 97,993 | 62,459 | 635,028 | 39,334 | 71,609 | 26,015 | 771,986 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. Functional categories are based on Classifications of Functions of Government (COFOG) Level 0. For more detailed breakdowns of expenditure, users should refer to the Country and Regional Analysis published by HM Treasury. | |||||||

| 2. Includes a number of components, of which the largest is consumption of fixed capital. For further details of contents please refer to publication tables and methodology guide. | |||||||

| 3. The UK figures contained in this table are equal to the figures in the UK public sector finances bulletin published by ONS in June 2018. The sum of the NUTS1 regions may not be equal to the United Kingdom due to rounding. | |||||||

Download this table Table 8: Total public sector expenditure for financial year ending (FYE) 2017, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (45.1 kB)As requested by users, identifiable and non-identifiable expenditure are now presented separately in this publication. Identifiable expenditure includes expenditure on services that can be identified as having been for the benefit of individuals or enterprises for a particular region. Non-identifiable expenditure is that which cannot be allocated to a particular region as it is incurred to benefit the UK as a whole, for example, military defence spending.

Table 9 provides a breakdown of identifiable and non-identifiable expenditure for each country and region, including on a per head basis. Non-identifiable expenditure is allocated to the NUTS1 regions using various methodologies. These include apportionment mainly using population or regional gross value added (GVA). As such, the trend of non-identifiable expenditure is driven largely by the population in an area.

Table 9: Identifiable and non-identifiable1 expenditure for financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by country and region

| Identifiable expenditure (£ million) | Identifiable expenditure per head (£)4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country or region | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 24,749 | 25,157 | 25,525 | 9,445 | 9,574 | 9,674 | |

| North West | 66,156 | 67,569 | 68,077 | 9,261 | 9,401 | 9,412 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 46,637 | 47,461 | 47,801 | 8,689 | 8,791 | 8,801 | |

| East Midlands | 38,037 | 38,496 | 39,129 | 8,185 | 8,209 | 8,260 | |

| West Midlands | 50,012 | 50,046 | 51,312 | 8,737 | 8,675 | 8,812 | |

| East of England | 48,147 | 49,381 | 49,995 | 7,982 | 8,110 | 8,144 | |

| London | 85,083 | 87,378 | 89,570 | 9,927 | 10,052 | 10,198 | |

| South East | 69,002 | 70,801 | 73,211 | 7,759 | 7,893 | 8,096 | |

| South West | 45,318 | 45,977 | 47,158 | 8,338 | 8,385 | 8,531 | |

| England | 473,140 | 482,262 | 491,779 | 8,692 | 8,783 | 8,884 | |

| Wales | 30,636 | 30,974 | 31,368 | 9,902 | 9,983 | 10,066 | |

| Scotland | 55,121 | 56,296 | 57,564 | 10,295 | 10,462 | 10,641 | |

| Northern Ireland | 20,333 | 20,222 | 20,562 | 11,031 | 10,906 | 11,029 | |

| UK | 579,231 | 589,754 | 601,272 | 8,949 | 9,039 | 9,145 | |

| Outside the UK expenditure2 | 26,895 | 25,649 | 24,230 | 416 | 393 | 369 | |

| Non-identifiable expenditure3 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

| North East | 3,286 | 3,446 | 3,442 | 1,254 | 1,311 | 1,304 | |

| North West | 9,145 | 9,515 | 9,596 | 1,280 | 1,324 | 1,327 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 6,735 | 7,085 | 7,092 | 1,255 | 1,312 | 1,306 | |

| East Midlands | 5,755 | 6,120 | 6,123 | 1,238 | 1,305 | 1,293 | |

| West Midlands | 7,265 | 7,609 | 7,675 | 1,269 | 1,319 | 1,318 | |

| East of England | 7,519 | 7,973 | 7,978 | 1,247 | 1,309 | 1,300 | |

| London | 11,332 | 11,704 | 12,013 | 1,322 | 1,346 | 1,368 | |

| South East | 11,394 | 11,889 | 12,016 | 1,281 | 1,325 | 1,329 | |

| South West | 6,568 | 7,085 | 7,011 | 1,208 | 1,292 | 1,268 | |

| England | 69,000 | 72,426 | 72,946 | 1,268 | 1,319 | 1,318 | |

| Wales | 3,447 | 3,738 | 3,844 | 1,114 | 1,205 | 1,234 | |

| Scotland | 6,488 | 6,682 | 6,676 | 1,212 | 1,242 | 1,234 | |

| Northern Ireland | 2,144 | 2,066 | 2,149 | 1,163 | 1,114 | 1,153 | |

| UK | 81,078 | 84,911 | 85,615 | 1,253 | 1,301 | 1,302 | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. Identifiable and non-identifiable expenditure as defined by HM Treasury in their Country and regional analysis publication and do not represent total expenditure in a country or region. For total expenditure figures (including accounting adjustments), refer to Table 7 of this publication. | |||||||

| 2. Outside the UK expenditure is allocated to each region using population, the breakdown is not presented here, but is provided in the data tables accompanying this publication. | |||||||

| 3. Non-identifiable expenditure is apportioned to each country and region using various methodologies, which are detailed in the methodology guide. | |||||||

| 4. The population estimates used in this publication are those published by ONS. | |||||||

Download this table Table 9: Identifiable and non-identifiable^1^ expenditure for financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2017, by country and region

.xls (45.6 kB)Notes for: Most countries and regions had a lower per head expenditure than the UK average

- For more information, see the ONS population estimates.

8. What’s changed in this release?

A number of data and methodological changes have been made since the last publication, which gives rise to revisions in the data when compared with last year’s estimates. Causes for revisions are described in this section and revisions to net fiscal balance are shown here, with revisions to main aggregates included in the data tables.

Changes to the monthly public sector finances

Since May 2017, routine data source updates, quality improvements and methodological changes have revised the underlying UK public sector finances (PSF) data that this bulletin is based on. Not all of these changes affect the country and regional public sector finances. Only those that affect UK net borrowing also have an impact on the country and regional public sector finances. These changes include:

Blue Book 2017 changes: through the annual Blue Book process, a number of data and methodological changes were taken on in the August 2017 PSF release

public sector employment-related pension schemes: data improvements to both unfunded and funded pension schemes were included in the August 2017 PSF release; further improvements to these data were made in the May 2018 PSF release

reclassification of Rail for London and data improvements to Tube Lines: these changes were included in the August 2017 PSF release

multilateral development banks: a methodological change that was introduced in the November 2017 PSF release

Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) levies: source data updates for recent and historical years were introduced in the November 2017 PSF release

interest receivable and payable: methodological improvements for recent and historical years were introduced in the November 2017 PSF release

Network Rail capital grants: capital grants received by Network Rail from other sectors were included from the November 2017 PSF release

Value Added Tax (VAT) on electronic services: a methodological change that was introduced in the March 2018 PSF release

Blue Book 2018 changes: a number of data and methodological changes were taken on in the May 2018 PSF release

routine data source updates: revisions occur to the monthly PSF as a result of provisional estimates being replaced by final data

Changes to methods for allocating revenue or expenditure to countries and regions

This year we have taken the opportunity to improve several apportionment methods that allocate UK data to the countries and regions. These improvements have been made to better reflect the incidence of taxes; or to account for differences between total expenditure on services and total managed expenditure by introducing new accounting adjustments; or to improve business processes.

Air Passenger Duty (APD)

We now use data from the Civil Aviation Authority’s (CAA) departing passenger survey to bring our APD methodology in line with those published by Scottish Government, HM Revenue and Customs and Scottish Fiscal Commission in their respective publications. The CAA data mean that we apply a consistent methodology across all countries and regions as well as allowing us to reflect more accurately the type of flights that APD is liable on.

Landfill Tax

The estimates in this year’s publication are based on European Waste Catalogue (EWC) codes, for which the environment agencies of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland collect data. This allows us to more accurately identify what kind of waste attracts the different rates of Landfill Tax at the country and regional level.

Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

We have sourced administrative data on both individual and trusts that pay CGT, whereas last year only data on individuals were available. As such, this is an improvement in coverage of our apportionment source data.

Levy-funded bodies

Apportionment now takes place at a more disaggregated level, reflecting the different industries that are levied.

Light dues

We now use port traffic data to apportion light dues.

Business processes

Some revisions have resulted in our data through improving our business processes for producing these statistics. These are generally quite small; however, the most notable revisions are to EU transactions.

Accounting adjustments

We have introduced new accounting adjustments to incorporate many of the UK PSF changes into our expenditure data, as they are not yet included in HM Treasury’s (HMT’s) Country and regional analysis.

Table 10a: Revisions to public sector net fiscal balance1 (geographic basis), financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2016, by UK countries and English regions

| Year (£ million) | UK2,3 | North East | North West | Yorkshire and The Humber | East Midlands | West Midlands | East of England | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999/00 | 3,470 | -23 | 152 | -37 | -171 | 89 | -99 | |||

| 2000/01 | 3,496 | -115 | 144 | -109 | -268 | 21 | -168 | |||

| 2001/02 | 4,410 | 3 | 365 | 84 | -84 | 145 | 23 | |||

| 2002/03 | 5,983 | 68 | 560 | 340 | -19 | 238 | 107 | |||

| 2003/04 | 9,597 | 244 | 1,037 | 507 | 161 | 534 | 382 | |||

| 2004/05 | 6,985 | 140 | 736 | 442 | -21 | 322 | 112 | |||

| 2005/06 | 4,232 | 68 | 473 | 342 | -103 | 164 | -72 | |||

| 2006/07 | 2,895 | 89 | 242 | 115 | -323 | -13 | -310 | |||

| 2007/08 | 2,566 | 7 | 113 | -11 | -418 | -87 | -603 | |||

| 2008/09 | 2,720 | 11 | 171 | 128 | -217 | 86 | -316 | |||

| 2009/10 | 1,465 | -53 | 14 | -90 | -330 | -12 | -611 | |||

| 2010/11 | 482 | -70 | -68 | -162 | -413 | -177 | -714 | |||

| 2011/12 | 698 | -148 | -175 | -239 | -414 | -223 | -781 | |||

| 2012/13 | -1,165 | -197 | -277 | -366 | -520 | -383 | -918 | |||

| 2013/14 | -4,233 | -267 | -922 | -602 | -668 | -655 | -1,129 | |||

| 2014/15 | -3,965 | -167 | -559 | -600 | -549 | -666 | -1,335 | |||

| 2015/16 | 325 | 384 | 212 | 115 | -188 | -393 | -1,065 | |||

| Year (£ million) | London | South East | South West | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | |||

| 1999/00 | 2,353 | 705 | -13 | 2,947 | 170 | 221 | 122 | |||

| 2000/01 | 2,638 | 874 | -82 | 2,936 | 66 | 406 | 88 | |||

| 2001/02 | 2,487 | 809 | 122 | 3,949 | -53 | 377 | 139 | |||

| 2002/03 | 2,585 | 988 | 253 | 5,125 | 108 | 549 | 201 | |||

| 2003/04 | 3,251 | 1,454 | 531 | 8,102 | 261 | 900 | 335 | |||

| 2004/05 | 2,802 | 1,023 | 257 | 5,813 | 263 | 652 | 255 | |||

| 2005/06 | 2,488 | 604 | 84 | 4,050 | -110 | 150 | 143 | |||

| 2006/07 | 2,537 | 453 | -155 | 2,634 | -129 | 262 | 130 | |||

| 2007/08 | 2,535 | 350 | -285 | 1,601 | -98 | 770 | 295 | |||

| 2008/09 | 2,345 | 259 | -92 | 2,376 | -172 | 346 | 169 | |||

| 2009/10 | 1,984 | 630 | -190 | 1,342 | -215 | 179 | 160 | |||

| 2010/11 | 2,162 | 575 | -163 | 970 | -318 | -209 | 38 | |||

| 2011/12 | 2,777 | 291 | -334 | 755 | -264 | 59 | 149 | |||

| 2012/13 | 2,575 | 81 | -449 | -455 | -463 | -263 | 16 | |||

| 2013/14 | 2,218 | -437 | -630 | -3,095 | -591 | -453 | -95 | |||

| 2014/15 | 2,090 | -323 | -1,057 | -3,169 | -530 | -379 | 112 | |||

| 2015/16 | 1,057 | 102 | 64 | 286 | -51 | 593 | -504 | |||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||

| 1. A positive revision to net fiscal balance is an increase, while a negative revision to net fiscal balance is a decrease. | ||||||||||

| 2. Revisions at the UK level are an accumulation of revisions between the May 2017 and May 2018 public secror finances, and therefore do not correspond to revisions shown in the May 2018 public secror finances bulletin. | ||||||||||

| 3. The sum of regional differences are not equal to total UK revisions in some years due to rounding. | ||||||||||

Download this table Table 10a: Revisions to public sector net fiscal balance^1^ (geographic basis), financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2016, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (41.0 kB)

Table 10b: Revisions to public sector net fiscal balance1 (population basis), financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2016, by UK countries and English regions

| Year (£ million) | UK2,3 | North East | North West | Yorkshire and The Humber | East Midlands | West Midlands | East of England |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999/00 | 3,470 | -30 | 154 | -36 | -171 | 90 | -100 |

| 2000/01 | 3,496 | -116 | 144 | -110 | -269 | 22 | -167 |

| 2001/02 | 4,410 | 2 | 367 | 81 | -85 | 145 | 21 |

| 2002/03 | 5,983 | 67 | 564 | 341 | -16 | 238 | 105 |

| 2003/04 | 9,597 | 241 | 1,037 | 511 | 161 | 534 | 379 |

| 2004/05 | 6,985 | 136 | 740 | 441 | -20 | 322 | 116 |

| 2005/06 | 4,232 | 73 | 473 | 338 | -107 | 164 | -64 |

| 2006/07 | 2,895 | 85 | 248 | 116 | -325 | -13 | -312 |

| 2007/08 | 2,566 | 12 | 111 | -11 | -418 | -87 | -607 |

| 2008/09 | 2,720 | 17 | 168 | 129 | -212 | 85 | -319 |

| 2009/10 | 1,465 | -54 | 14 | -92 | -328 | -12 | -610 |

| 2010/11 | 482 | -75 | -68 | -157 | -414 | -177 | -713 |

| 2011/12 | 698 | -144 | -177 | -247 | -415 | -223 | -782 |

| 2012/13 | -1,165 | -196 | -277 | -367 | -523 | -383 | -915 |

| 2013/14 | -4,233 | -267 | -922 | -604 | -667 | -654 | -1,128 |

| 2014/15 | -3,965 | -168 | -562 | -599 | -548 | -665 | -1,334 |

| 2015/16 | 325 | 384 | 212 | 115 | -189 | -394 | -1,065 |

| Year (£ million) | London | South East | South West | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland |

| 1999/00 | 2,354 | 705 | -11 | 2,953 | 170 | 224 | 122 |

| 2000/01 | 2,638 | 875 | -84 | 2,935 | 66 | 407 | 88 |

| 2001/02 | 2,488 | 811 | 123 | 3,949 | -53 | 376 | 139 |

| 2002/03 | 2,585 | 989 | 249 | 5,124 | 108 | 549 | 201 |

| 2003/04 | 3,251 | 1,455 | 530 | 8,101 | 261 | 900 | 336 |

| 2004/05 | 2,803 | 1,022 | 254 | 5,814 | 263 | 652 | 254 |

| 2005/06 | 2,488 | 603 | 80 | 4,050 | -110 | 150 | 143 |

| 2006/07 | 2,537 | 449 | -152 | 2,634 | -129 | 262 | 130 |

| 2007/08 | 2,536 | 350 | -284 | 1,602 | -98 | 768 | 295 |

| 2008/09 | 2,345 | 257 | -93 | 2,377 | -174 | 347 | 170 |

| 2009/10 | 1,984 | 628 | -187 | 1,342 | -215 | 178 | 160 |

| 2010/11 | 2,161 | 573 | -160 | 970 | -318 | -209 | 38 |

| 2011/12 | 2,778 | 296 | -330 | 756 | -264 | 59 | 148 |

| 2012/13 | 2,575 | 83 | -450 | -454 | -463 | -263 | 15 |

| 2013/14 | 2,218 | -435 | -632 | -3,094 | -590 | -453 | -94 |

| 2014/15 | 2,090 | -322 | -1,057 | -3,168 | -530 | -379 | 112 |

| 2015/16 | 1,056 | 103 | 64 | 286 | -51 | 594 | -504 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. A positive revision to net fiscal balance is an increase, while a negative revision to net fiscal balance is a decrease. | |||||||

| 2. Revisions at the UK level are an accumulation of revisions between the May 2017 and May 2018 public sector finance statistics, and therefore do not correspond to revisions shown in the May 2018 Public Secror Finances. | |||||||

| 3. The sum of regional differences are not equal to total UK revisions in some years due to rounding. | |||||||

Download this table Table 10b: Revisions to public sector net fiscal balance^1^ (population basis), financial year ending (FYE) 2000 to FYE 2016, by UK countries and English regions

.xls (31.7 kB)Presentational changes

This year we have provided breakdowns of identifiable and non-identifiable expenditure in response to user feedback received as part of our last consultation.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. Subnational public sector finances consultation

Over July to September 2017, we consulted on the first country and regional public sector finances bulletin as well as possible future publication of public finances data for local areas below Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics: NUTS1 level. At the same time, we published a scoping study on subregional public sector finances, which detailed and evaluated methodologies and data sources currently used to estimate public sector revenue.

Feedback on the first country and regional public sector finances was overall very positive and respondents provided many examples of how they made use of the NUTS1 level estimates provided in the bulletin. Some suggestions for possible improvements were offered, such as producing workplace-based estimates alongside the residence-based estimates or providing breakdowns for identifiable and non-identifiable expenditure. The latter we have introduced in this bulletin and we have included producing workplace-based estimates in our future workplan.

The subregional scoping study was also well received although opinions were divided on the usefulness of net fiscal balance at subregional levels as well as what role we would play in the production of data for smaller geographies.

As a result of the consultation we have decided to continue the publication of the country and regional public sector finances bulletin on an annual basis, as well as continuing to develop the statistics further based on feedback received. However, given concerns over the robustness of data and resource constraints, we do not intend to engage directly in the production of net fiscal balances for subregional geographies at this stage. However, we intend to continue offering support and advice on methodologies and data sources to organisations and areas wishing to produce their own estimates.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys11. Future developments

As described at the start of this publication, Experimental Statistics are statistics still under development, as such; we welcome and encourage user feedback about how they used these statistics; what they have found useful; and what they would potentially like to see in the future.

Areas of development and improvement we plan to focus on over the next year include, but are not limited to:

moving the annual publication timing to late November or early December, from 2019; this means that the lag will be reduced from 13 months to seven months after the end of the reporting period and our statistics will be available at a similar time to HM Revenue and Customs’ (HMRC) Disaggregation of tax receipts and HM Treasury’s Country and regional analysis, which are published in October and November respectively

improving methods and data sources to refine allocation of UK revenue or expenditure to the NUTS1 regions, while also working to further align methods with those used by HMRC and Scottish Government in their publications

working with colleagues in devolved administrations, HMRC, Office for Budget Responsibility and the Scottish Funding Council to align and improve methodologies of those taxes due to be devolved

investigating extending the current presentation to include expenditure by type of expenditure (for examples, pay, goods and services) and not just function, as well as producing sectoral breakdowns (for example, central government, local government, public corporations)

investigating the feasibility of introducing work-placed estimates for some revenues to complement the residential-based estimates currently produced

working towards achieving National Statistics accreditation

12. Quality and methodology

How are the country and regional estimates calculated?

The total UK public sector revenue and expenditure reported in this publication are the same as those in the May 2018 public sector finances (PSF) bulletin. However, the country and regional allocation of revenue and expenditure data in this publication are largely based on various assumptions. This is because taxes are generally not levied or collected on a regional basis and most spending is planned to benefit a category of individuals and enterprises irrespective of location.

Estimates of public sector revenue are based on the concept of “who pays”. Revenue is attributed to the countries and regions of the UK using apportionment methods, such as the use of surveys, population shares and gross value added (GVA) shares.

Estimates of public sector expenditure are based on the concept of “who benefits”. Expenditure in each of the countries and regions of the UK is calculated using methods that attempt to apportion expenditure based on the location of the residents or enterprises who have benefited from expenditure of a particular department or body. This can be challenging as most public spending is planned to benefit categories of individuals and enterprises irrespective of location and only a minority of public spending is planned on a regional basis.

The UK data used in this publication are sourced from the PSF bulletin and are apportioned to Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics: NUTS1 regions using various methodologies. Expenditure data are sourced from HM Treasury’s Country and regional analysis (CRA), with few adjustments made to bring the data in line with PSF aggregates.

The CRA data are based on HM Treasury’s measure of “total expenditure on services” and accounting adjustments are used to move to “total managed expenditure”, which is equivalent to that recorded in the UK PSF. As such, the expenditure statistics in this publication are presented on the functional classification used by HM Treasury in their expenditure publications.

For further information on the statistical methods used to allocate revenue and expenditure items please refer to the country and regional public sector finances methodology guide. This guide describes the data and methods used to attribute revenue and expenditure to countries and regions. It also compares the method used with that followed in other publications (see Section 6 “Links to related statistics”) and highlights any potential weaknesses in the data and/or methodology.

What is the relationship between these statistics and those of the UK public sector finances?

The UK public sector finances (PSF) bulletin is a monthly publication jointly produced by Office for National Statistics (ONS) and HM Treasury. By contrast this is an annual publication produced solely by ONS. However, the two publications are closely linked as the UK totals published in the monthly PSF bulletin form the UK expenditure and revenue totals that must be apportioned to the NUTS1 country and regions of the UK. The total UK expenditure and revenue in this publication match those in the May 2018 PSF bulletin.

At the UK level the equivalent of the net fiscal balance is termed public sector net borrowing excluding public sector banks (PSNB ex). A positive PSNB ex (and positive net fiscal balance) indicates a deficit, whereas negative values indicate a surplus. The net fiscal balance is not to be interpreted as the actual borrowing of a country or region; it is instead a statistical construct indicative of the difference between the revenue raised from residents and enterprises in a region and the public sector expenditure from which those residents and corporations benefit.

Are our figures adjusted for inflation?

All monetary values in the PSF bulletin are expressed in “current prices‟, that is, they represent the price in the period to which the expenditure or revenue relates and are not adjusted for inflation.

To compare data over long time periods commentators often discuss changes over time to fiscal aggregates in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) ratios. GDP represents the value of all the goods and services currently produced by an economy in a period of time.

Quality

We have developed Guidelines for measuring statistical quality; these are based upon the five European Statistical System (ESS) quality dimensions, which are:

relevance – the degree to which statistics meet current and potential needs of the users

accuracy and reliability – the closeness between an estimated result and the (unknown) true value

timeliness and punctuality – the lapse of time between the period to which the data refer and publication of the estimate; and the time lag between the actual and planned dates of publication

accessibility and clarity – the ease with which users can access the data, the format(s) in which the data are available, the availability of supporting information and the extent to which easily comprehensible metadata are available, where these metadata are necessary to give a full understanding of the statistical data

coherence and comparability – the degree to which the statistical processes, by which two or more outputs are generated, use the same concepts and harmonised methods; and the degree to which data can be compared over time, region or other domain

The quality of our statistics is partially dependent on the quality of our data sources. While these guidelines are concerned with the quality of those data sources to the extent that it impacts the quality of our statistics, comprehensive information on a particular data source should be obtained through the links provided throughout the methodology guide.

Relevance

The aim of these statistics is to provide users with information on what public sector expenditure has occurred, for the benefit of residents or enterprises, in each country or region of the UK and what public sector revenues have been raised in each country or region. This is with the aim of supporting the devolution debate. The statistics refer to financial years running from April to March and are based on NUTS1 boundaries, which separate Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and nine English regions.

Consultations have been held in 2016 and 2017 to gather information about the requirements of users and feedback on the 2017 publication. Consultation responses and actions that have been taken as a result appear throughout the bulletin and methodology guide. There is wide support for the completeness, consistency and comparability between countries and regions that the publication provides.

Where it has not been possible to take a consistent approach to all countries and regions, this is stated in the methodology guide. This has been kept to a minimum and is most notable in the case of Corporation Tax (offshore) and Petroleum Revenue Tax. Apportionment methods are described in detail in the methodology guide, which also lists data sources.

Accuracy and reliability

Accuracy depends upon the absence of errors. Statistics that rely upon a broad range of data sources are inevitably affected by various types of error. The main sources of error are described and assessed in this section.

Sampling error

Sampling error occurs when statistics are based upon random samples from the population of interest. For example, the Living Costs and Food Survey, data from which is used to apportion tobacco duties (and, indirectly, alcohol duties), uses expenditure data from a random sample of individuals to estimate the average expenditure of the UK population. While certain statistical controls will increase the likelihood that the sample is representative of the population, the estimates are unlikely to be the same as the population averages. Moreover, different samples will produce different estimates. The variability amongst the individuals in the sample can be used to estimate the variability between all the samples that might have been taken and therefore the accuracy of the estimate.

Much of the data used comes from administrative sources and is therefore not subject to sampling error. However, a non-trivial amount of apportionment data are from sample surveys. Measures of the sampling error present in these surveys can be used to construct estimates of the resulting sampling error in our statistics. Unfortunately, these measures are not always produced and when they are produced it is not always at a granularity that suits our purposes.

Due to the range of data sources involved and the work needed to gather the necessary information, it has not been possible to include measures of sampling error in this year’s publication. These measures are currently being developed and we expect to publish them in the next release.

Imputation

In statistics, imputation is the substitution of missing values with estimated quantities. Imputation is performed in the production of some of our source data and in the processing of certain parts of that data.