Cynnwys

- Main points

- Your role in shaping our future products and outputs

- Population and migration statistics we already estimate and why we want to expand our range

- The fundamental aspects of population definition

- Condition-based definitions

- Qualifying status-based definitions

- Population present

- Glossary

- Related links

- Cite this article

1. Main points

This article explores new ways of estimating migration and the population to enhance our existing statistics.

These include estimates of the population present in a place within a time period.

We look at various ways to estimate the contribution of different patterns of migration to the population, including possible ways of isolating estimates of international students from other types of migrants.

We ask for feedback and suggestions from our users on our alternative definitions of population and migration flows.

2. Your role in shaping our future products and outputs

The purpose of this article is to focus on alternative ways that we could define populations and migration flows. We have included many suggestions of ways to do this and would value your feedback on these and your own ideas.

Your input is essential. We are asking you to think beyond what is currently available, tell us where you see gaps in population and migration statistics and why having this information would be useful to you. Please send your feedback on this article to pop.info@ons.gov.uk.

This article supported the public consultation on the future of population and migration statistics, that ran from 29 June 2023 to 26 October 2023. Visit the future of population and migration statistics pages or subscribe to our newsletter to stay up to date with upcoming events and our future plans.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Population and migration statistics we already estimate and why we want to expand our range

Both population and long-term international migration (LTIM) statistics are used extensively by policy makers, academics and service providers, and we will continue to produce them.

Our Population estimates are official estimates of the number of usual residents in the UK. They are a benchmark or point of reference for many of our surveys, denominators for a wide range of per capita statistics and support international comparisons.

Our LTIM statistics are official estimates of migrants arriving in or leaving the UK for 12 months or more. These are currently experimental statistics to reflect the ongoing development of our methods to produce provisional long-term international migration estimates, as we move to using administrative data rather than surveys. They are an important component of population change and are aligned with the UN definition for long-term international migration (PDF, 5.0MB).

Today, populations are more mobile than in past decades, as seen by the change in mobility during the recent coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (World Migration Report 2022). We know that there are people living and staying in the UK who are not covered by our official population estimates, because they do not meet the traditional census definition of a usual resident. Movers with shorter or repeat patterns of mobility are not represented in our LTIM numbers.

Our transformation of population and migration estimates uses the wealth of information available within administrative data in secure, lawful and ethical ways to produce improved aggregate statistics. We will have greater flexibility to provide statistics on specific population groups and different patterns of international mobility. We will be able to provide some insight into the impact of temporary population change.

We want to know what other population and migration estimates you require. This could include:

defining a usual resident or migrant using different criteria

estimating specific groups in our population not covered by our current estimates

concentrating on populations present in an area at a particular time (rather than counting them at their place of usual residence)

4. The fundamental aspects of population definition

Time and place

Time and place are fundamental aspects in deciding when and where to estimate a population, whether it is point in time population estimates (stocks) or movements into and out of a population (flows).

Many definitions are time-related; they depend on the amount of time a person is at their usual residence, how long they have lived there (or intend to live there) or whether they are there on a given day. The length of stay of a mover is crucial to the classification of a migrant and which population they join or leave.

Estimates are needed at many different levels of geography; UK, constituent countries, region and sub-regional geographies, and health or crime decision making geographies. They provide clear geographical boundaries for inclusion or exclusion within a population and a way to classify the origin or destination of movers. Estimating mobility at different levels of geography produces different challenges in applying time conditions, as evidence of movement over short distances may be harder to locate or infer from administrative data than movement over longer distances or international travel.

In our modern world, contributors to the domestic economy do not necessarily have a place of usual residence in the UK. For example, someone might work in the UK during the week but have a usual residence in France that they return to each weekend. Administrative data sources, such as tax receipts, allow estimation of those contributing to the economy, opening up new definitions. The challenges and benefits of trying to align population and economic definitions are discussed further in Impact of Migration on National Accounts: A UK Perspective (PDF,224KB).

Working out how to implement aspects of time and place is the next step in estimating a population. This might include creating rules for where to complete a census form, how to identify and estimate flows of internal migrants or how to infer presence in an area from interaction with an administrative database.

Information on time and place are essential to include in your suggestions for new types of population and migration estimates. We need to understand the time periods that you need data for, the ideal frequency of these proposed statistics and the level of geography that is required.

A further element to consider is the timeliness of the estimates. Using the best possible information at the time might mean revising a provisional estimate when more data become available. For example, once people have been in the country for a year or more, we can have more certainty about where they are, but we might not want to wait that long to produce international migration estimates.

Target and complementary populations

A population is any group of people who share one or more characteristics, measured within a particular time period and usually within a particular geographical area. A "target population" includes those we wish to focus on from a larger overall total population.

The "complementary population" contains those within the total population who do not fit into the target population. Over time, both populations change as people become eligible or ineligible to be in the target population. Further change occurs as people join or leave the total population, as a result of natural change (births and deaths) or movement (mobility and migration).

For example, if we are interested in employed adults living in a particular area, then our target population would be those who are employed. The complementary population would include everyone who was not employed, for example children, retired, self-employed and unemployed.

Inclusion in the target population may be condition-based and/or confirmed by a qualifying status. Conversely, it may be the result of being physically present in a population during a particular time period.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Condition-based definitions

Usual residents

In line with UN recommendations, we use time and place conditions to define someone as a usual resident of the UK. A usual resident is someone who stays or intends to stay in an area for 12 months or more. A further condition enables short absences by usual residents to be disregarded when looking at an individual's length of stay. This is a logical inclusion, as people do not tend to change their permanent place of residence while away for a short time period, such as a holiday.

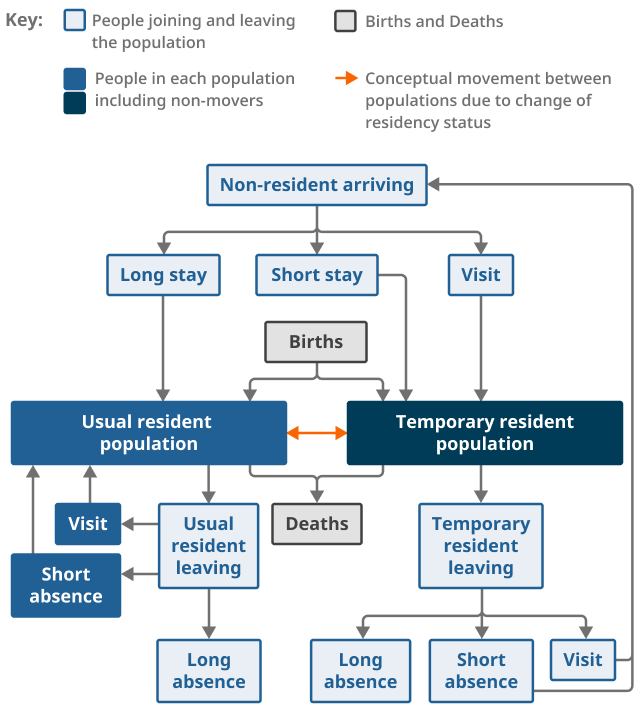

Figure 1 shows a conceptual framework of the usual resident and temporary resident populations (stocks) and the flows resulting in population change. In this instance, the target population is the usual resident population and the temporary population is our complementary population. The flow of people between each population is represented by the double-headed orange arrow. This conceptual framework can be applied over any time period and at any level of geography, with different conditions applied to the length of stay associated with usual residence.

Figure 1: A conceptual framework of how people move into and out of populations

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 1: A conceptual framework of how people move into and out of populations

.png (52.9 kB)In practice, defining the population who are usual residents is not straightforward. There are always some circumstances that make it harder to apply these conditions.

For example, the impact of mortality on population change is less clear for a small minority of deaths. Deaths within the UK are assumed to be to the usual resident population; if no usual residence is given, they are attributed to the person's location at the time of death. This includes homeless people within the UK and those whose usual residence is abroad and are temporarily in the UK. UK usual residents who die abroad are not removed from population estimates, as they are not included in Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality statistics. Current methods assume that these are compensating errors which make little impact on usual resident population estimates.

As part of the transformation of population statistics, the ONS has produced timely, reliable admin-based population estimates that have a better level of quality over the 10-year period than current mid-year estimates of the usual resident population.

The Dynamic Population Model (DPM) combines data sources to estimate the usual resident population in England and Wales. Inputs are births, deaths, international and internal migration, as well as the Statistical Population Dataset (SPD). The SPD approximates the usual resident population down to small areas using administrative data, with activity rules used to determine record inclusions.

The DPM and SPD models are adaptable to applying other rules to data, opening up opportunities to explore different population estimates.

Temporary residents

The temporary resident population is complementary to the usual resident population. It includes people with many different circumstances or statuses. It is an important component of change within a total population, particularly for short-term mobility.

In Figure 1, the temporary resident population includes short-term non-resident movers, visitors and transfers from the usual resident population.

Although excluded from that area's official population estimate (of usual residents), an area's total population rises and falls with the mobility patterns of temporary residents or visitors. They impact local services and facilities, such as housing and health care. They contribute to the local economy by supplementing the labour market and interacting with hospitality and recreational services.

A temporary resident in one area is probably a usual resident elsewhere at the same point in time. This might be within the UK, or abroad, where they still meet the conditions of usual residency. For example, someone who works in the UK for one week a month would join the UK temporary population but could be a usual resident in another country. Similarly, a UK student is classified as a usual resident at their term time address, but a temporary resident where they spend holiday periods.

Applying different time conditions to the length of stay in a location can produce alternative definitions for populations and migration flows. For example, a usual resident could be defined using a:

six-month or nine-month length of stay; includes those living in an area and using the local services for at least six or nine months, but who did not stay for a whole year, such as seasonal workers

12-month stay within a 16-month period; extends the period of time within which a temporary resident might be considered to be a usual resident, avoiding exclusion because of a short absence, this definition is currently used in Australia as can be seen in the Australian Bureau of Statistics' Overseas Migration methodology

majority of the time basis, cumulatively present in an area for more than 50% of a 12-month period; would include those whose time in an area was split over several substantial visits, such as circular and repeat migrants

fractional calculation; a percentage addition is added to the population estimate at different locations, reflecting time spent there, for example 10% in London, 20% in Edinburgh, and 70% abroad

These alternative population estimates would include people who marginally breach a 12-month length of stay condition, but may not reflect the static population who are long-term residents. A proportional approach may better reflect service use for those with multiple homes.

International flows

The mobility flows in Figure 1 represent movements into and out of usual and temporary resident populations. International mobility encompasses both long-term international migration and other moves across international boundaries.

We use the condition-based UN recommended definition for long-term international migration (PDF, 5.0MB). Further information on our latest long-term international migration (LTIM) estimates of moves into and out of the country for 12 months or more are available on our International migration page.

In its 2021 recommendations, the UN noted the important role of temporary international mobility (moves) in population change, and their impact on societies, over much shorter periods of time. See more information in the Final Report on Conceptual frameworks and Concepts and Definitions on International Migration from the UN Expert Group on Migration Statistics, 27 April 2021.

Shorter stays or visits allows for multiple events within a particular period of time. The definition for a short stay should clarify whether the length of stay is from a single stay or cumulative trips and how it accounts for very short stops (such as transfers between flights). Multiple trips also make it harder to define at which point a mover is a new arrival or a returning migrant.

We use information on travel behaviour and visa status within Home Office Borders and Immigration data to research patterns of short-term international migration, to determine if we can produce estimates from these data. We have produced exploratory research estimates of short-term immigration to the UK for newly arrived non-EU nationals. These are early, indicative estimates of migrants who:

are not included in our LTIM calculations

have visited the UK at least once in the year following their first arrival in the UK

have a total length of their completed stays (in the 12 months after their first arrival) that sum to between 1 month and less than 12 months

were not in the country in the previous 12 months before their first arrival (and are therefore considered new arrivals)

This is an area of ongoing research and these estimates are experimental. They are not directly comparable with estimates of short-term migration we have previously published from the International Passenger Survey (IPS) as they are based on different data sources, methodology and assumptions. They are also not comparable with LTIM estimates for these time periods.

| Length of cumulative stay | Year ending June 2019 | Year ending June 2020 | Year ending June 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 months up to 12 months | 50,000 | 40,000 | 30,000 |

| 6 months up to 9 months | 50,000 | 50,000 | 30,000 |

| 3 months up to 6 months | 160,000 | 110,000 | 70,000 |

| 1 month up to 3 months | 420,000 | 250,000 | 70,000 |

Download this table Table 1: Short-term international immigration of non-EU nationals

.xls .csvThe decrease in the total number of short-term migrants from year ending (YE) June 2019 to YE June 2021 reflects the decrease in passenger arrivals to the UK because of travel restrictions during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. See further details in the Home Office's article How many people come to the UK each year (including visitors?)

We have further research to do to refine our method. We need to understand why mid-2019 numbers are materially higher than IPS estimates. This may reflect definitional differences (for classifying short-term international migrants) or other causes. Further information on our previous estimates can be found in our Short-term international migration 01, Citizenship by main reason for migration - flows, England and Wales (Discontinued after mid-2019) dataset.

We have been investigating other data, such as Advanced Passenger Information that travellers provide to airlines and travel companies and mobile phone data. These could provide more timely information on trends in travel and migration. These data could potentially provide a timely signal to nowcast (provide real-time indicators on) our headline estimates.

These estimates are an example of how short-term or alternative types of migrants could be defined. We are currently focusing on immigration. The data support flexibility in how we determine an immigrant. We can specify a minimum length of stay, whether this needs to be a single visit or is cumulative over several visits, and the duration over which we look for evidence in the UK.

We will use your feedback to decide which of these options to explore in more detail and provide a research update on the method in November 2023.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Qualifying status-based definitions

A condition-based population can be further defined to include people who have a particular status or characteristic.

Administrative data provide information on both activity and characteristics. They may include people who interact with a service or process, such as paying tax, but are not usual residents, as measured by a census.

Populations defined by a qualifying status could include:

ownership of a second home; allowing users to understand the relationship between housing and usual residency

usual residents of a communal establishment, such as a care home; focusing on a particular section of society

currently in paid work or contributing to the economy, regardless of place; potentially a more appropriate population estimate for some per capita statistics

The possibilities and challenges of using a qualifying status to define a population are explored further using the example of international students.

International students in the UK

An international student is currently defined as someone who arrives in the UK to study and remains for a period of 12-months or more. In line with the current UN definition of a long-term migrant (PDF, 5.0MB), international students are included in our estimates of long-term immigration.

Students are an important interest group to many users and some question whether they should be included in our long-term international migration (LTIM) estimates. They are often considered part of the temporary population who arrive to study and leave once their studies are completed, often with periods abroad outside of term time. However, many who come to study go on to obtain work visas or become British citizens. It is important to consider how much students contribute to population change over time.

Several reasons make isolating international students challenging:

1) International student migration routes

Studying is a temporary period in someone's life, with start and end points. We can identify long-term non-EU student migrants by their visa type (study) in Home Office Borders and Immigration data. This administrative data source provides visa start and end dates and travel dates, providing arrival time and length of stay of each student.

Not all students require a study visa to study in the UK. For students who are EU nationals, we use Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) data, which provide information on student enrolments. Methods to estimate non-EU and EU migrants are explained in our Long-term international migration research update.

Some long-term international students are not identified in either method. Migrants who arrive through alternative routes may choose to study after arrival in the UK, but do not need to acquire a student visa to do so. Such routes include the Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme, British Nationals (Overseas) (BNO) or those with EU Settled Status (EUSS).

2) International student status change

Students' plans may change. Our Visa journeys and student outcomes article shows that for students with visas ending in the 2018 to 2019 academic year, 35% successfully applied for new visas (such as for work and/or further study) and remained in the UK.

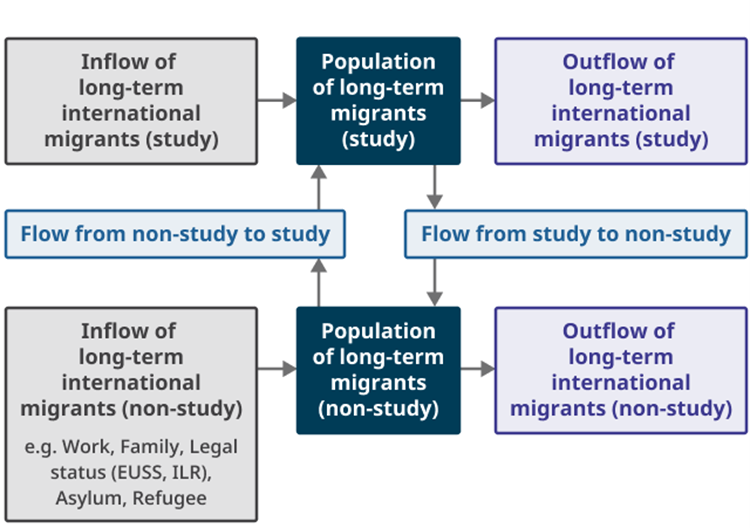

This interaction between students and other reasons for migration means we cannot treat students in isolation. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Populations and flows by reason for migration - study and non-study

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

European Union Settled Status (EUSS).

Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR).

Download this image Figure 2: Populations and flows by reason for migration - study and non-study

.png (157.9 kB)Figure 2 shows the inflows and outflows of long-term migrants to the UK, split by whether their main reason for migration is to study. Between arrival and departure, the populations of international students and all non-study migrants are separate. Students move into the other reasons for migration population if they stop studying and start working or gain British citizenship. Those who arrive for non-study reasons can move into the international student population if they start studying.

Treating students as temporary migrants and excluding them from LTIM estimates could create error in net long-term migration because:

not including students in our immigration estimates, but including those who stayed beyond their student visa in emigration estimates, as emigrating workers for example, would lead to underestimation of net migration

not including students who, post-study, transfer to an alternative route and subsequently stay in the UK, would lead to net migration under-estimates

including those who enter via non-student routes in our immigration estimates, but then excluding their emigration after a transfer to a student visa would lead to overestimation of net migration

not including those who we cannot identify as a student (Ukraine, BNO, EUSS, British) in the student population, leaving them in the general population, would lead to overestimation of net migration

Possible ways to quantify students in our net migration estimates

There are two possible ways of quantifying students in our net migration estimates that would avoid the inaccuracies mentioned previously.

1. Using the reason for immigration and emigration based on a non-EU migrant's visa at first arrival to the UK.

It is theoretically possible to estimate a net flow that removes students using immigration by reason, and emigration by original reason for arrival, although it has some limitations.

Our most recent long-term international migration (LTIM) statistics include estimates by the reasons for migration. Our datasets include a breakdown by reason for all immigration, and for the emigration of non-EU nationals by their visa at first arrival. These improvements enable a greater understanding of the contribution students have in our net migration estimates.

The advantage of this method is that it gives an idea of the role of student visas in the net migration to the UK.

However, this method currently ignores the movement between these two populations (shown by the flows in the centre of Figure 2), and the proportion of time a person might spend studying or working while in the UK. It also ignores the contribution to long-term population change. For example, someone who arrived to study for a year, then worked for three years, would be counted out as a student and the contribution of the work element of their stay would be missed. We might emigrate people as students who arrived on a student visa then worked for decades. We do not currently know the scale of this issue and would need to do further research to understand and potentially adjust for it.

The new graduate visa route allows graduates to seek work in the UK for a period of time after studying and removes some of the distinction between the various contributions of different visa routes to population change.

Currently we can only estimate emigration by visa at first arrival for non-EU nationals, who, along with their dependents, account for 89% of all student and dependent visas. We are developing a method to estimate this for EU students and their dependents. Possibly, a student net figure would initially be based on non-EU migrants only. This would be available five months after the reference year, as per our current estimates.

2. Adjusting the student inflow to account for transfers to other visas.

Using Home Office Borders and Immigration data, we can follow "migrant journeys" for non-EU nationals with study visas. This involves following the yearly intake of students (cohort) from their first visa at arrival through to their final visa or naturalisation in the UK population.

It would not be practical to wait for the visa transfer or emigration of each student. For timeliness, we would explore estimating the proportion of students who transfer onto a secondary non-student visa, producing a five-year annual rolling average. We could apply this to produce an alternative estimate of net migration that excludes students who enter the UK but do not transfer to an alternative reason for migration.

We do not have equivalent information for students who do not require a visa. We need to explore differences in post-study behaviours between those with and without study visas.

Predicting migrant behaviours in the absence of observed behaviours reduces the accuracy of our estimates, especially when policy changes are introduced. For example, the new graduate visa enables migrants to work in the UK for at least two years after their course end date. This increases the likelihood of remaining after studying, but for now an adjustment for this would be based on assumptions rather than observation.

There are also challenges to this approach that require further research. Further analysis is needed on whether historical trends predict future behaviours. This may influence the best timeframe for an accurate rolling annual average. Similarly, further research could determine the feasibility of longitudinal analysis using visa identification numbers.

This definition would likely need a system of timely, provisional estimates followed by more accurate final estimates.

We are keen to understand which approach is more useful for understanding the role of students in our net migration estimates, and how users would use them. We will use your feedback to decide which of these options to explore in more detail and provide a research update on the method in November 2023.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Population present

An alternative concept for defining a population is to include everyone who is physically present at a particular place at a certain time. The size of these populations can fluctuate in many ways. For example, student flows enlarge university towns during term-time and shrink areas without universities as people leave for study. Holiday destinations have seasonal fluctuations. In commercial areas there can be significant variation in population present at weekends compared with weekdays. In entertainment areas, day-time and night-time populations can differ.

A fundamental aspect of population present statistics is the unit of measure used and how changes in magnitude are presented. For very short stays, such as a visit or day-time presence, it is not necessarily how many people within the population move, but the number of moves undertaken that is most useful. For example in our Overseas travel and tourism data, we estimate the number of completed visits by UK residents abroad and overseas residents in the UK.

We are exploring innovative methods for estimating population present. This includes using administrative data in research to explore the feasibility of estimating the population of small areas by specific times of day, taking account of population mobility. This exploratory research can be found in Population 24/7 – A method to account for daily population mobility in spatiotemporal population estimates on the UK Statistics Authority website (PDF, 983KB).

Suggestions for other populations that could be defined by a population present status include:

workplace and workday populations; who is present in an area during the standard working week

evening and weekend populations; who is present in an area outside the standard working week

monthly, quarterly, or seasonal populations

8. Glossary

Administrative data

Collections of data maintained for administrative reasons, for example, registrations, transactions, or record keeping. They are used for operational purposes and their statistical use is secondary. These sources are typically managed by other government bodies.

Alternative definitions of international migration

Other ways of defining international migration that is not the long-term international migration (LTIM) definition used in our statistics.

Home Office Borders and Immigration data

Combines data from different administrative sources to link an individual's travel in or out of the UK with their immigration history. This system has data for all non-European Economic Area (non-EEA) visa holders.

International mobility

International mobility includes all movements that cross international borders within a given time period.

International student

In this article, an international student is someone who moves to the UK from abroad for a period of at least a year for the purpose of studying. This may differ from definitions in other articles which may be based on age, nationality and whether they are studying in higher education.

Long-term international migration

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) Centre for International Migration uses the UN-recommended definition of a long-term international migrant (PDF, 5.0MB): "A person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence for a period of at least a year (12 months), so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence."

Short-term international migration

Short-term international migration statistics estimate the flow (or movement) to England and Wales of people from outside the UK, whose visit or stay lasted at least one month and not longer than 12 months.

Temporary resident

A temporary resident of any area is anyone who does not meet the conditions to be a usual resident. This includes visitors, short-term residents, and short-term migrants.

Usual resident

People who live or intend to live in an area for 12 months or more. As such, temporary residents including visitors, short-term residents and short-term migrants are excluded.

Nowcasts

Nowcasts are estimates of activity in the current period, or the most recent period for which no official estimate is available.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys10. Cite this article

Office for National Statistics (ONS), released 25 May 2023, ONS website, article, Population and migration estimates - exploring alternative definitions: May 2023