Cynnwys

- Main points

- Things you need to know about this release

- Taxes and benefits lead to income being shared more equally

- Half of households in the UK receive more in benefits than they paid in taxes

- Households with main earner between 25 and 64 paid more in taxes than they received in benefits

- Cash benefits have the largest effect on reducing income inequality

- Housing benefit is the most progressive cash benefit, though the State Pension makes the largest contribution to the overall progressivity of cash benefits

- Economic context

- What’s changed in this bulletin?

- Quality and methodology

- Users and uses of these statistics

- Related statistics and analysis

1. Main points

In the financial year ending 2016, the average income of the richest fifth of households before taxes and benefits was £84,700 per year, 12 times greater than that of the poorest fifth (£7,200 per year). An increase in the average income from employment for the poorest fifth of households has reduced this ratio from 14 to 1 in the financial year ending 2015.

The ratio between the average income of the top and bottom fifth of households (£63,300 and £17,200 respectively) is reduced to less than 4 to 1 after accounting for benefits (both cash and in kind) and taxes (both direct and indirect).

On average, households paid £7,800 per year in direct taxes (such as Income Tax, National Insurance contributions and Council Tax), equivalent to 18.7% of their gross income. Richer households pay higher proportions of their income in direct taxes than poorer households.

The poorest households paid more of their disposable income in indirect taxes (such as Value Added Tax (VAT) and duties on alcohol and fuel) than the richest (27.0% and 14.4% respectively) and therefore indirect taxes cause an increase in income inequality.

There has been a 14% increase in the average amount paid in Insurance Premium Tax for all households, reflecting the November 2015 increase in the standard rate from 6% to 9.5%.

Overall, 50.5% of all households received more in benefits (including in kind benefits such as education) than they paid in taxes (direct and indirect). This is equivalent to 13.7 million households and continues the downward trend seen since the financial year ending 2011.

Households where the main earner is aged between 25 and 64 paid more in taxes (direct and indirect) than they received in benefits (including in kind benefits), whilst the reverse was true for those aged 65 and over.

Despite being less progressive (targeted towards reducing inequality) than many of the other benefits, the State Pension has consistently made the largest contribution to the overall progressivity of cash benefits over the past 22 years.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Things you need to know about this release

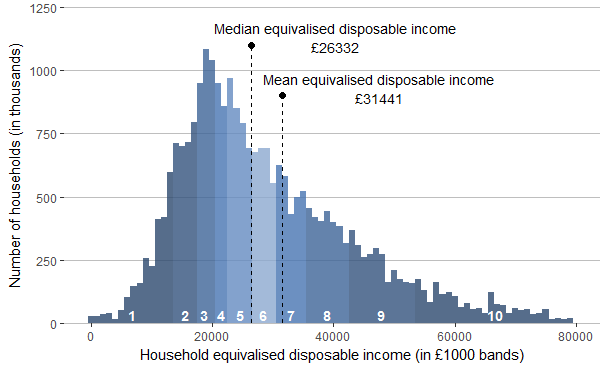

This bulletin looks at two main measures of average household income, the mean and the median (Figure 1). The median is used when looking at the average income of a particular group of households, while the mean is used when looking at the sources of earnings, benefits and taxes that make up the overall income measures.

The mean simply divides the total income of households by the number of households. A limitation of using the mean for this purpose is that it can be influenced by just a few households with very high incomes and therefore does not necessarily reflect the standard of living of the “typical” household.

Many researchers argue that growth in median household incomes provides a better measure of how people’s well-being has changed over time. The median household income is the income of what would be the middle household, if all households in the UK were sorted in a list from poorest to richest. As it represents the middle of the income distribution, the median household income provides a good indication of the standard of living of the “typical” household in terms of income.

Figure 1: Distribution of UK household disposable income, financial year ending 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 1: Distribution of UK household disposable income, financial year ending 2016

.png (7.4 kB) .xls (31.2 kB)How is income redistributed across the population?

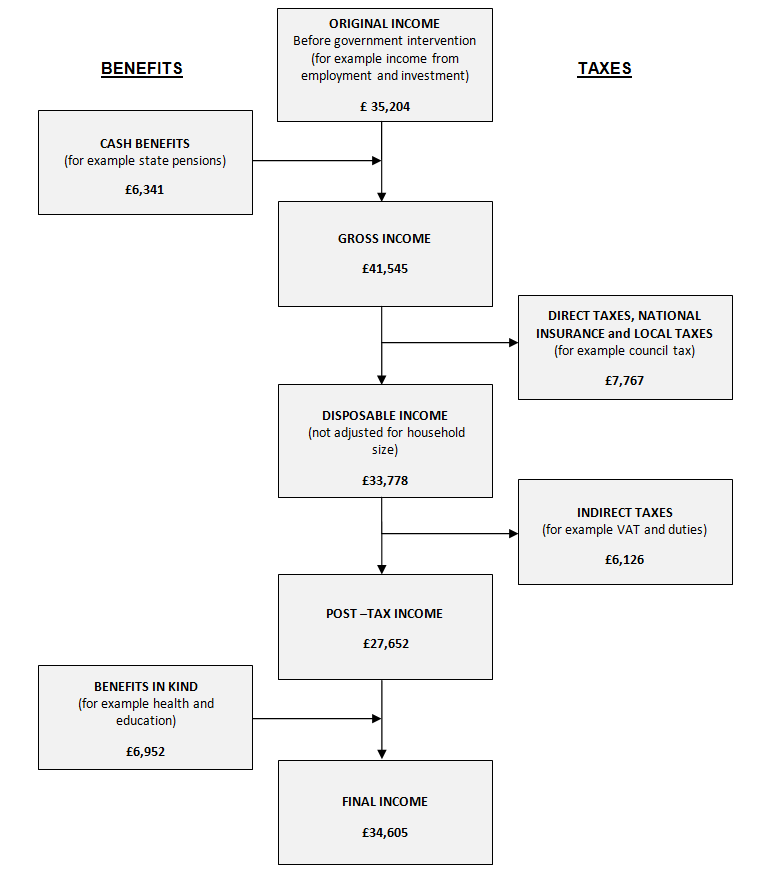

This release looks at how taxes and benefits affect the distribution of income in the UK and breaks this process into five stages. These are summarised in Figure 2 and in this section:

- Household members begin with income from employment, private pensions, investments and other non-government sources. This is referred to as “original income”.

- Households then receive income from cash benefits. The sum of cash benefits and original income is referred to as “gross income”.

- Households then pay direct taxes. Gross income minus direct taxes is referred to as “disposable income”.

- Indirect taxes are then paid via expenditure. Disposable income minus indirect taxes is referred to as “post-tax income”.

- Households finally receive a benefit from services (benefits in kind). Benefits in kind plus post-tax income is referred to as “final income”.

Figure 2: Stages in the redistribution of income

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 2: Stages in the redistribution of income

.png (25.5 kB)What does it mean for a benefit or tax to be progressive?

A tax is considered to be progressive when high-income groups face a higher average tax rate than low-income groups. If those with higher incomes pay a higher amount but still face a lower average tax rate, then the tax is considered regressive; similarly, cash benefits are progressive where they account for a larger share of low-income groups’ income

Progressivity is measured through the Kakwani index (Kakwani, 1977). For taxes, a positive value indicates that the tax is progressive overall and acting to reduce inequality. The larger the value, the more progressive the tax is. A negative value would indicate that the tax is regressive and therefore contributing to increased inequality.

Conversely, for benefits, a negative value indicates that the benefits are progressive and acting to reduce the level of inequality. Again, the larger the negative value, the more progressive the benefit is.

How do we make comparisons over time?

This bulletin looks at how main estimates of household incomes and inequality have changed over time. To make robust comparisons historic data have been adjusted for the effects of inflation and are equivalised to take account of changes in household composition. More information on the details of these adjustments can be found in the Quality and Methodology section of this bulletin.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Half of households in the UK receive more in benefits than they paid in taxes

Overall, in the financial year ending (fye) 2016 (April 2015 to March 2016), there were 50.5% of all households receiving more in benefits (including in-kind benefits such as education) than they paid in taxes (direct and indirect) (Figure 8). This equates to 13.7 million households and continues the downward trend seen since fye 2011 (53.5%) but remains above the proportions seen before the economic downturn.

Looking at this figure separately for non-retired households and retired households, the trend seen for non-retired households mirrors that for all households, except that lower percentages of non-retired households receive more in benefits than they pay in taxes, 37.2% in fye 2016.

In contrast, in fye 2016, of all retired households 88.0% received more in benefits than they paid in taxes, reflecting the classification of the State Pension as a cash benefit in this analysis. A retired household is defined as a household where the income of retired household members accounts for the majority of the total household gross income. This figure is lower than its fye 2010 peak of 92.4% and the lowest since fye 2001.

Figure 8: Percentage of households receiving more in benefits than paid in taxes, financial year ending 1997 to 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Financial year ending 1997 is the earliest year presented in this chart as changes to the underlying source data caused a break in this series at that point. Caution should therefore be taken in making comparisons with earlier years on this measure.

Download this chart Figure 8: Percentage of households receiving more in benefits than paid in taxes, financial year ending 1997 to 2016

Image .csv .xls5. Households with main earner between 25 and 64 paid more in taxes than they received in benefits

The effects of taxes and benefits are felt differently by households in different age groups (Figure 9). On average, in the financial year ending (fye) 2016 (April 2015 to March 2016), households with a household head aged between 25 and 64 paid more in taxes (direct and indirect) than they received in benefits (including in-kind benefits), whilst the reverse was true for those aged 65 and over, with those in their late 40s on average paying the most in taxes (£18,300). Households where the main earner was in their early 40s, whilst also paying a lot in taxes (£17,800 on average), also received the highest average amount in benefits of those below State Pension age (£15,400), due mainly to the benefit in kind received from state-provided education (£6,900).

For households with where the main earner is aged 65 and over, the State Pension and Pension Credit was the largest component of the benefits received, followed by the benefit derived from the National Health Service, which becomes increasingly important as age increases. Those households with heads under the age of 25 were the other age group who, on average, received more in benefits than they paid in taxes.

Figure 9: The effects of taxes and benefits by age of the main earner in the household, financial year ending 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 9: The effects of taxes and benefits by age of the main earner in the household, financial year ending 2016

Image .csv .xlsThe effect of taxes and benefits on redistributing income for households in different age groups can be seen when comparing income at the different stages of redistribution for these households (Figure 10). This shows that there is much less variation across different age groups in either average disposable or final income, than there is in original income.

Figure 10: Household income by age of the main earner in household, financial year ending 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 10: Household income by age of the main earner in household, financial year ending 2016

Image .csv .xlsIn fye 2016, for households with heads aged 25 to 64, on average, their original income (before any taxes and benefits) is higher than their disposable income. However, this picture changes for those with heads over the age of 65, where average disposable income exceeds original income.

For most age groups, average final income is relatively close to disposable income. One exception is among those households with heads between the ages of 50 and 64, where average final income is lower, reflecting in part the lower in-kind education benefits received compared with younger households, due to a smaller proportion of households with school age children. The other main exception is for those households with heads aged 75 or above, for whom NHS services become increasingly valuable, increasing the average value of final income.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Cash benefits have the largest effect on reducing income inequality

There are a number of different ways in which inequality of household income can be presented and summarised. Perhaps the most widely used measure internationally is the Gini coefficient. Gini coefficients can vary between 0 and 100 and the lower the value, the more equally household income is distributed.

The extent to which cash benefits, direct taxes and indirect taxes work together to affect income inequality can be seen by comparing the Gini coefficients of original, gross, disposable and post-tax incomes. Cash benefits have the largest effect on reducing income inequality, in the financial year ending (fye) 2016 (April 2015 to March 2016), reducing the Gini coefficient from 49.3% for original income to 35.0% for gross income (Figure 11). Direct taxes act to further reduce it, to 31.6%, however, indirect taxes have the opposite effect and in fye 2016 the Gini for post-tax income was 35.4%, meaning that overall, taxes have a negligible effect on income inequality.

Figure 11: Impact of cash benefits and taxes on Gini coefficient, financial year ending 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- PP=Percentage point

Download this image Figure 11: Impact of cash benefits and taxes on Gini coefficient, financial year ending 2016

.PNG (16.5 kB) .xls (26.1 kB)Analysis of Gini coefficients for all households over time (Figure 12) shows cash benefits have consistently the largest effect on reducing inequality, though there has been some variation in the size of this effect. In 1977, cash benefits reduced inequality by 13 percentage points (pp). This increased during the early 1980s and by 1984 cash benefits reduced inequality by 17pp. However, during the late 1980s, their redistributive impact weakened and by 1990 cash benefits reduced inequality by only 13pp again. More recently, there has been a slight increase in the effect of cash benefits in reducing income inequality, rising from 13.5pp in fye 2007 to 14.3 in fye 2016.

Figure 12: Gini coefficients for different income measures, 1977 to financial year ending 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Equivalised using the modified-OECD scale.

- An improved process for calculating the Gini Coefficient has been implemented which has resulted in a change to the levels of rounding applied. Although not significant, there are minor differences to previously published Gini estimates.

Download this chart Figure 12: Gini coefficients for different income measures, 1977 to financial year ending 2016

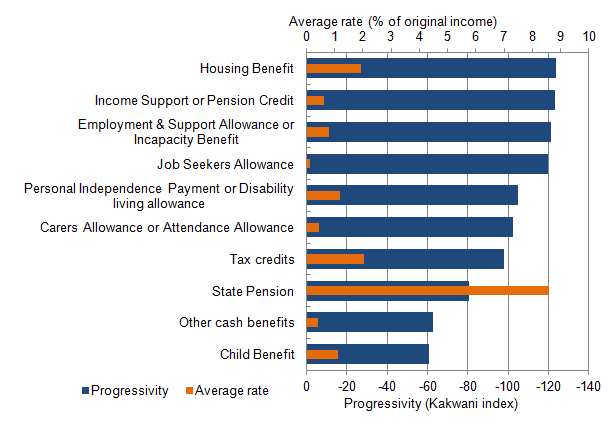

Image .csv .xls7. Housing benefit is the most progressive cash benefit, though the State Pension makes the largest contribution to the overall progressivity of cash benefits

Looking in more detail at the redistributive effect of benefits, this is dependent on two factors:

- the relative size of the benefit as a proportion of income; this can be referred to as the average benefit rate

- the progressivity of the benefit: a benefit is considered progressive when it accounts for a larger share of low-income groups’ income than high-income groups – progressivity is measured through the Kakwani index (Kakwani, 1977); for benefits, a negative value indicates that the benefits are progressive and acting to reduce the level of inequality – the larger the negative value, the more progressive the benefit is

Figure 13: Progressivity and average rate of different cash benefits

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 13: Progressivity and average rate of different cash benefits

.png (15.5 kB) .xls (26.6 kB)Figure 13 shows both the size and progressivity of individual cash benefits in the financial year ending (fye) 2016 (April 2015 to March 2016). This shows that whilst all the main cash benefits are progressive, the level of progressivity varies considerably. The most progressive cash benefits in fye 2016 were Pension Credit, Housing Benefit and Income Support, meaning that these were the benefits that were targeted most towards reducing inequality.

Child Benefit was the least progressive of the benefits examined, with the State Pension also less progressive than many other cash benefits.

Figure 14 shows how important individual cash benefits contribute to the overall progressivity of cash benefits and how this has changed over a 20-year period. Throughout this time, the State Pension has made the largest contribution to the overall progressivity of benefits, despite being less progressive than many of the other benefits. This is because, as shown in Figure 13, the State Pension makes up a large proportion of the total cash benefits received by households.

More detailed analysis of the impact of taxes and benefits on inequality over time using a range of measures can be found in the article The Effects of Taxes and Benefits on Income Inequality, 1977 to 2014/15.

Figure 14: Contribution of main benefits to overall progressivity of cash benefits, financial year ending 1995 to financial year ending 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 14: Contribution of main benefits to overall progressivity of cash benefits, financial year ending 1995 to financial year ending 2016

Image .csv .xlsFigure 14 highlights the effect of some of the changes to the benefits system over this period. The replacement of Family Credit with Working Families’ Tax Credit in 1999, followed by the introduction of Child Tax Credit and Working Tax Credit in 2003, has lead to tax credits making an increasing contribution to the overall progressiveness of cash benefits, with tax credits making the third- largest contribution in fye 2016 (after Housing Benefit and the State Pension).

By contrast, the contribution to overall progressivity made by benefits such as Income Support, Pension Credit and Incapacity Benefit, and most recently, Employment and Support Allowance, has reduced over time. In fye 1995, these benefits together accounted for 25% of the overall progressivity of cash benefits. By fye 2016, the contribution of these benefits had reduced to 10%. This effect is the main reason why overall progressivity has generally fallen over this period, despite the increasing contribution of tax credits.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Economic context

In the financial year ending (fye) 2016 (April 2015 to March 2016), outcomes in the UK labour market were likely to have directly affected household incomes. In the 3 months to March 2016, both the number of people in employment (31.6 million) and the headline employment rate (74.2%) were at their highest levels since records began. Over the same period, the unemployment rate was 5.1%, lower than a year earlier (5.6%).

Other headline indicators in the May 2016 Labour Market release suggested the labour market performed strongly in the latter months of fye 2016, which typically correlates with increasing nominal earnings growth. However, after increasing growth in early 2015, nominal regular pay growth eased and stood at 2.2% in the 3 months to March 2016.

Figure 15: Contributions to the growth of real regular pay: Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation and the growth of average regular weekly earnings, 2008 to 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- The data for regular pay presents the 3 months on 3 months a year ago growth rate for the month at the end of the period (the final data is for January to March 2016).

Download this chart Figure 15: Contributions to the growth of real regular pay: Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation and the growth of average regular weekly earnings, 2008 to 2016

Image .csv .xlsThe rate of price inflation in the economy is also an important component that determines households’ real income growth. There was persistent low inflation in fye 2016, driven partly by a fall in oil prices. This low inflation combined with nominal pay increases has meant that real wages continued to grow in fye 2016 as they did towards the end of the second half of the previous financial year, following several years of falling real wages after the economic downturn.

In fye 2016, real output in the UK economy increased 1.9% on the preceding 12 months, continuing a period of growth following the fye 2009 economic downturn. By the end of the period, the UK had recorded 13 quarters of consecutive economic growth. While aggregate real GDP surpassed its pre-downturn peak in Quarter 3 (July to September) 2013, GDP per head took until Quarter 4 (October to December) 2015 to overtake its pre-downturn peak.

Figure 16: Measures of economic well-being: gross domestic product per head and net national disposable Income per head, chained volume measure, Quarter 1 2005 to Quarter 1 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 16: Measures of economic well-being: gross domestic product per head and net national disposable Income per head, chained volume measure, Quarter 1 2005 to Quarter 1 2016

Image .csv .xlsFigure 16 presents two alternative measures of economic well-being – gross domestic product per head and net national disposable income (NNDI) per head. NNDI per head makes two adjustments to GDP per head: firstly, subtracts the consumption of capital – the wear and tear resulting from assets being used in production – from GDP, capturing the net value of production and secondly, includes a measure of net international investment income.

Despite the indicators tracking reasonably well until 2011, NNDI per head has followed a slightly weaker growth path than GDP per head since late 2011. This continued into fye 2016. Between Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2015 and Quarter 1 2016, GDP per head increased by 1.1% while NNDI per head remained unchanged.

These relatively marked differences reflect some of the more detailed developments in the UK economy. In particular, the unchanged NNDI per head over the financial year partly reflects the fall in the UK’s balance on income with the rest of the world: over this period, UK earnings overseas have grown less strongly than the earnings of overseas agents in the UK. Between Quarter 1 2015 and Quarter 1 2016, the balance of earnings on foreign direct investment (FDI) (the difference between earnings from direct investment abroad and from foreign direct investment in the UK) decreased from a surplus of £2.5 billion to a deficit of £2.0 billion. This trend is largely accounted for by the fall in the relative rate of return on UK assets held overseas.

More information on the divergence of GDP per head and NNDI per head since late 2011 can be found in our Economic Well-being: Quarter 3, July to Sept 2016 bulletin.

Overall, these two measures compare relatively well with the strong growth observed in median household disposable income since fye 2014, based on the effects of taxes and benefits on household income (ETB) and nowcast estimates. More recently, growth in median household income more closely resembles GDP per head growth rather than NNDI per head growth. This possibly reflects that the fall in balance on income with the rest of the world has not impacted.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. What’s changed in this bulletin?

From the financial year ending (fye) 2016 (April 2015 to March 2016), where income comparisons are made over time, estimates have been deflated to fye 2016 prices using the Consumer Prices Index including owner-occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) deflator. Previous publications have used the implied expenditure deflator for the household final consumption expenditure (HHFCE).

See the statement on future of consumer inflation statistics for further information.

Figure 17 shows the effect on the time series for mean equivalised disposable income between 1977 and fye 2015. The pre-downturn peak of mean household income in fye 2008 is estimated to be approximately £1,000 lower when deflated using CPIH, however, the longer-term trend since 1977 remains broadly consistent with the series deflated using HHFCE.

Figure 17: Time series of mean equivalised disposable income, 1977 to financial year ending 2015, UK (fye 2015 prices deflated by household final consumption expenditure and CPIH)

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 17: Time series of mean equivalised disposable income, 1977 to financial year ending 2015, UK (fye 2015 prices deflated by household final consumption expenditure and CPIH)

Image .csv .xls10. Quality and methodology

The Effects of taxes and benefits upon household income Quality and Methodology Information document contains important information on:

- the strengths and limitations of the data

- the quality of the output, including the accuracy of the data and how it compares with related data

- uses and users

- how the output was created

Analysis in this bulletin is based on our long-running effects of taxes and benefits on household income (ETB) series. The ETB series has been produced each year since the early 1960s. Historical tables, including data from 1977 onwards are also published today, along with an implied deflator for the household sector, which can be applied to adjust for the effects of inflation. Differences in the methods and concepts used mean that it is not possible to produce consistent tables for the years prior to 1977 and only relatively limited comparisons are possible for these early years. All comparisons with previous years are also affected by sampling error.

Glossary

Equivalisation: Income quintile groups are based on a ranking of households by equivalised disposable income. Equivalisation is the process of accounting for the fact that households with many members are likely to need a higher income to achieve the same standard of living as households with fewer members. Equivalisation takes into account the number of people living in the household and their ages, acknowledging that while a household with two people in it will need more money to sustain the same living standards as one with a single person, the two-person household is unlikely to need double the income.

This analysis uses the modified-OECD equivalisation scale.

Gini coefficients: The most widely used summary measure of inequality in the distribution of household income is the Gini coefficient. The lower the value of the Gini coefficient, the more equally household income is distributed. A Gini coefficient of 0 would indicate perfect equality where every member of the population has exactly the same income, while a Gini coefficient of 100 would indicate that one person would have all the income.

Income quintiles: Households are grouped into quintiles (or fifths) based on their equivalised disposable income. The richest quintile is the 20% of households with the highest equivalised disposable income. Similarly, the poorest quintile is the 20% of households with the lowest equivalised disposable income.

Household income: This analysis uses several different measures of household income. Original income (before taxes and benefits) includes income from wages and salaries, self-employment, private pensions and investments. Gross income includes all original income plus cash benefits provided by the state. Disposable income is that which is available for consumption and is equal to gross income less direct taxes.

Retired persons and households: A retired person is defined as anyone who describes themselves (in the Living Costs and Food Survey) as “retired” or anyone over minimum National Insurance pension age describing themselves as “unoccupied” or “sick or injured but not intending to seek work”. A retired household is defined as one where the combined income of retired members amounts to at least half the total gross income of the household.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys11. Users and uses of these statistics

The effects of taxes and benefits on household income (ETB) statistics are of particular interest to HM Treasury (HMT), HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) in determining policies on taxation and benefits and in preparing budget and pre-budget reports. Analyses by HMT based on this series, as well as the underlying Living Costs and Food (LCF) dataset, are published alongside the budget and autumn statement. A dataset, based on that used to produce these statistics, is used by HMT in conjunction with the Family Resources Survey (FRS) in their Intra-Governmental Tax and Benefit Microsimulation Model (IGOTM). This is used to model possible tax and benefit changes before policy changes are decided and announced.

In addition to policy uses in government, the ETB statistics are frequently used and referenced in research work by academia, think tanks and articles in the media. These pieces often examine the effect of government policy, or are used to advance public understanding of tax and benefit matters. The data used to produce this release are made available to other researchers via the UK Data Service.

These statistics play an important role in providing an insight to the public on how material living standards and the distributional effect of government policy on taxes and benefits have changed over time for different groups of households. This new release was developed in response to strong user demand for more timely data on some of the main indicators and trends previously published in the Effects of Taxes and Benefits on Household Income statistical bulletin and associated ad hoc releases.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys