Cynnwys

- Main points

- Economic well-being indicators at-a-glance

- Things you need to know about this release

- What were the main changes in economic well-being in Quarter 2 2017?

- Spotlight: Regional trends in economic well-being

- Economic sentiment

- Economic well-being indicators already published

- Links to related statistics

- Quality and methodology

1. Main points

- Gross domestic product (GDP) per head grew by 0.1% in Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017 compared with the previous quarter and increased by 0.9% compared with the same quarter a year ago (Quarter 2 2016).

- Net national disposable income (NNDI) per head increased by 2.0% between Quarter 2 2016 and Quarter 2 2017, due mainly to a £6.4 billion increase in the income received from the UK’s foreign direct investment from abroad.

- Despite improvements in both GDP per head and NNDI per head, real household disposable income (RHDI) per head declined by 1.1% in Quarter 2 2017 compared with the same quarter a year ago; this was the fourth consecutive quarter that RHDI per head has decreased – the longest period of consistent negative growth since the end of 2011.

- For the first time in two years, consumers reported a worsening of their perception of their own financial situation in Quarter 2 2017.

2. Economic well-being indicators at-a-glance

Figure 1: Economic well-being indicators, UK, Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

Embed code

3. Things you need to know about this release

This release reports measures of economic well-being in the UK. Rather than focusing on traditional measures such as gross domestic product (GDP) alone, these indicators aim to provide a more rounded and comprehensive basis for assessing changes in material well-being.

We prefer to measure economic well-being on a range of measures rather than a composite index. The framework and indicators used in this release were outlined in Economic Well-being, Framework and Indicators, published in November 2014.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. What were the main changes in economic well-being in Quarter 2 2017?

Figure 2: Four measures of economic well-being, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Q1 refers to Quarter 1 (January to March), Q2 refers to Quarter 2 (April to June), Q3 (July to September) and Q4 refers to Quarter 4 (October to December).

Download this chart Figure 2: Four measures of economic well-being, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

Image .csv .xlsReal GDP per head

Growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) per head was 0.1% in Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017 compared with the previous quarter – unchanged from the growth rate in Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2017. This was a slower growth rate than the 0.3% quarterly increase in GDP, due to population growth over the same period.

GDP per head growth in Quarter 2 2017 was 0.2 percentage points lower than the average quarterly growth rate over the past four years.

Real net national disposable income (NNDI) per head

Real net national disposable income (NNDI) per head increased by 2.0% between Quarter 2 2016 and Quarter 2 2017, compared with a 0.9% increase in GDP per head over the same period. Growth in NNDI per head recorded in Quarter 2 2017 continues the marked improvement in the series beginning in Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2016.

As shown in the “Economic well-being indicators at a glance” section, NNDI per head is a better representation than GDP of the income available to all residents in the UK to spend or save. There are two main differences between GDP per head and NNDI per head.

First, not all income generated by production in the UK will be payable to UK residents. For example, a country whose firms or assets are predominantly owned by foreign investors may well have high levels of production, but a lower national income once profits and rents flowing abroad are taken into account. As a result, the income available to residents would be less than that implied by measures such as GDP.

Second, NNDI per head is adjusted for capital consumption. GDP is “gross” in the sense that it does not adjust for capital depreciation, that is, the day-to-day wear and tear on vehicles, machinery, buildings and other fixed capital used in the productive process. It treats such consumption of capital as no different from any other form of consumption, but most people would not regard depreciation as adding to their material well-being.

As highlighted in Figure 2, NNDI per head and GDP per head have followed slightly different growth paths in recent years. The differences between these two series’ growth rates are largely explained by changes in the amount of income earned from UK residents’ investments overseas. For instance, between Quarter 4 2015 and Quarter 2 2017, NNDI per head grew by 5.0%, compared with 1.1% growth in GDP per head. Over this period, the amount of income earned by UK residents on their foreign direct investments increased, on average, by £1.2 billion per quarter. This contrasts with period during Quarter 2 2011 and Quarter 4 2015, during which GDP per head and NNDI per head grew by 7.0% and 2.1% respectively. Slower growth in NNDI per head compared with GDP per head is largely accounted for by an average decline of £1.1 billion per quarter in the income that UK residents received from investments abroad.

More detailed analysis on the contributions to growth in NNDI and the relationship with the balance of primary incomes was presented in Economic well-being: Quarter 4, Oct to Dec 2016.

Household income

In Quarter 2 2017, real households disposable income (RHDI) per head declined by 1.1% compared with the same quarter a year ago (Quarter 2 2016). Quarter 2 2017 marks the fourth consecutive quarter that RHDI per head has decreased – the longest period of consistent negative growth since the end of 2011. Despite this fall, RHDI per head still remains 3.2% above its pre-economic downturn level.

Figure 3: Contributions to quarter-on-same-quarter-a-year-ago growth in real household disposable income, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2013 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Q1 refers to Quarter 1 (January to March), Q2 refers to Quarter 2 (April to June), Q3 (July to September) and Q4 refers to Quarter 4 (October to December).

- Real household disposable income includes non profit institutions serving households (NPISH).

- Contributions may not sum due to rounding.

Download this chart Figure 3: Contributions to quarter-on-same-quarter-a-year-ago growth in real household disposable income, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2013 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

Image .csv .xlsDespite growth in both NNDI per head and GDP per head in Quarter 2 2017 compared with the same quarter a year ago, RHDI per head continued to decline. Figure 2 highlights the contributions to growth from different components of RHDI per head. It shows that, higher prices facing households had a negative contribution to RHDI growth in Quarter 2 2017 compared with the same quarter a year ago – contributing negative 2.3 percentage points to the 1.1% decline. However, growth in wages and salaries (in nominal terms) supported RHDI per head, contributing 2.7 percentage points.

Changes to measures of real household disposable income

This quarter we publish, for the first time, separate income accounts for the households and NPISH sectors. As part of the process of separating these accounts, we took the opportunity to improve the measurement of both sectors, by updating methodologies and drawing on new data sources. Improving the household, private non-financial corporations and non-profit institutions serving households sectors' non-financial accounts, provides more information on the changes introduced.

Figure 4: Quarter-on-same-quarter-a-year-ago growth in real households disposable income per head, and impact of methodological improvements, chain volume measure

UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Q1 refers to Quarter 1 (January to March), Q2 refers to Quarter 2 (April to June), Q3 refers to Quarter 3 (July to September) and Q4 refers to Quarter 4 (October to December).

Download this chart Figure 4: Quarter-on-same-quarter-a-year-ago growth in real households disposable income per head, and impact of methodological improvements, chain volume measure

Image .csv .xlsFigure 4 presents three series. The first reports the quarterly growth rate, on an annual basis, of RHDI per head. The second and third series demonstrate the impact of separating the household and NPISH sectors, and the methodological improvements introduced respectively. The impact on RHDI per head growth due to the separation of accounts has been relatively minor over the period since Quarter 1 2008. Over this period, average quarterly growth in both RHDI per head and RHDI and NPISH per head was 0.1%.

The impact of methodological improvements on the measurement of RHDI is more noticeable. While average annual growth in both the revised and previous measure of RHDI per head is 0.1% per head since Quarter 1 2008, there are distinct periods where these revisions had greater impact. For instance, between Quarter 2 2009 and Quarter 4 2010, RHDI per head growth was revised by an average of negative 1.3% per quarter. Similarly, between Quarter 2 2013 and Quarter 3 2015, growth was revised upwards by an average of 0.8% per quarter.

These revisions have altered the path of RHDI per head, telling a slightly different story of economic well-being following the economic downturn. As GDP began to fall in mid-2008, Figure 2 highlights that RHDI per head remained relatively resilient. By Quarter 2 2009, the revised measure of RHDI per head was 1.4% above its pre-economic downturn level, compared with 3.1% as indicated by the previously published measure.

This initial improvement in real household income per head was a result of several factors. Firstly, household incomes were buoyed by falling mortgage repayments as a result of historic lows in the interest rate. Additionally, automatic stabilisers – such as reduced Income Tax payments and increased benefits as a result of lower employment – supported incomes during worsening conditions in the labour market. However, moving into early 2010, the impact of these factors wore off and inflation rose. Prices grew more strongly than household income and therefore, over time, people found that their income purchased a lower quantity of goods and services.

Following this, RHDI per head remained under its pre-economic downturn level for 14 consecutive quarters (compared with five quarters according to the previous estimate) from Quarter 1 2010 until Quarter 2 2013. Between Quarter 3 2014 and Quarter 3 2015, RHDI per head had a general upward trend because of the lower impact of prices, increasing by 7.0%. However, the series decreased by 2.7% from Quarter 3 2015 to Quarter 1 2017, due mainly to the onset of price pressures.

Household expenditure

Growth in real household spending per head (excluding non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH)) was 0.1% in Quarter 2 2017 compared with the previous quarter. This means that household spending per head has grown for 10 quarters in a row – the longest period of consecutive growth since 2003.

As highlighted in Figure 1, real household spending per head (excluding NPISH) in Quarter 2 2017 was 0.8% higher than its pre-economic downturn level. This is despite real household disposable income per head (excluding NPISH) in Quarter 2 2017 being 3.2% above its pre-economic downturn level. As a result, the household-only saving ratio decreased from 7.3 to 5.4 between Quarter 2 2016 to Quarter 2 2017.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Spotlight: Regional trends in economic well-being

The economic well-being indicators described so far are reported at the national level. This section will examine regional differences, using previously published data, for the indicators where data is available: gross disposable household income (GDHI) per head and median income.

Regional GVA per head and GDHI per head

The nearest equivalent metric to GDP per head that is available at regional level is gross value added (GVA) per head. At the national level GDP per head is regarded as a useful indicator for economic well-being and the health of the economy. However, at regional level, we advise that GVA per head should not be used as either an estimate or proxy for economic well-being. This is because the value of GVA per head at regional level is impacted by the level of net-commuting flows and for places with high levels of net in- or out- commuting, GVA per head ceases to be a useful economic well-being (or economic performance) proxy.

Instead, when assessing regional economic well-being the preferred regional accounts measure is gross disposable household income (GDHI) per head. This measures the total amount of money that households have for spending or saving, after they have paid direct and indirect taxes and received any direct benefits, divided by the population of each region.

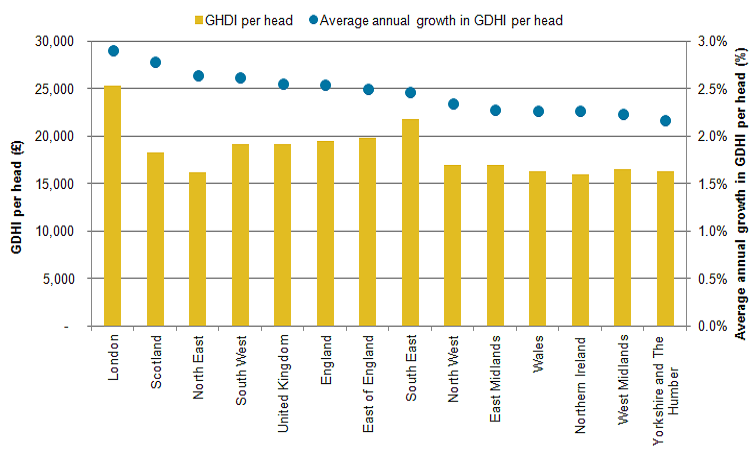

Figure 5: Gross disposable household income (GDHI) per head in 2015 and average annual growth, by UK region, 2005 to 2015, current prices

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures may not sum to totals as a result of rounding.

- 2015 estimates are provisional.

Download this image Figure 5: Gross disposable household income (GDHI) per head in 2015 and average annual growth, by UK region, 2005 to 2015, current prices

.png (54.6 kB) .xlsx (57.2 kB)London had the highest GDHI per head in 2015 where, on average, each person had £25,293 available to spend or save. Northern Ireland had the lowest at £15,913. This compares with a UK average of £19,106.

Between 2005 and 2015, London and Scotland had the highest average annual growth in GDHI per head among all UK regions – 2.9% and 2.8% per year respectively. West Midlands, and Yorkshire and The Humber, on the other hand, had the lowest average annual growth – both at 2.2%.

Figure 6: Contributions to gross disposable household income growth, North East, East of England, Yorkshire and The Humber, East Midlands, 2003 to 2015, current prices

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures may not sum to totals as a result of rounding.

- 2015 estimates are provisional.

Download this image Figure 6: Contributions to gross disposable household income growth, North East, East of England, Yorkshire and The Humber, East Midlands, 2003 to 2015, current prices

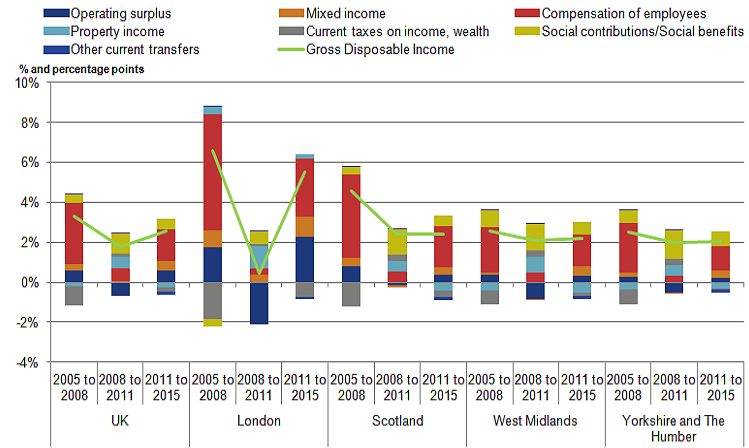

.png (112.3 kB) .xlsx (10.4 kB)Figure 6 provides more insight into the variations in growth rates of GDHI per head across regions. It examines the role of different contributions to GDHI per head growth for the regions that had the highest GDHI growth between 2005 to 2015 – London and Scotland – and the lowest growth – West Midlands, and Yorkshire and The Humber.

In all the regions considered, growth in compensation of employees per head provided the greatest contribution to GDHI growth per head before the economic crisis. Compensation of employees includes the wages and salaries payable in cash or in kind to an employee in a return for work done and the social insurance contributions payable by employers.

During the years of economic downturn – 2008 to 2011 – average GDHI per head fell in all four regions. However, the fall in income was mitigated by an increase in social contributions and social benefits, as automatic stabilisers via the taxes and benefits system supported households, amidst falling contributions from compensation of employees. After 2012, the impact of social contributions and social benefits declined. Larger contributions from compensation of employees during these years characterised the recoveries of London and Scotland, compared with the West Midlands, and Yorkshire and The Humber.

Regional median income

The analysis presented so far has focused on an aggregate measure of income. While this measure was presented on a per person basis, it is important to note that GDHI per head is not a direct estimate of the income of a typical individual or household. As such, for measures of median income, or for data on distributions of income, it is necessary to examine alternative sources. Regional measures of median income are sourced from the households below average income data from Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), and are based on the Family Resources Survey. Due to limitations in sample size, median income by regions is calculated as a three-year average.

This section therefore compares regional growth rates of median income, allowing some assessment of the equality of overall economic gains. This analysis reports median income both before and after accounting for housing costs, therefore accounting for the regional variations in rents and other housing costs. Housing costs include: rent (gross of housing benefit); water rates, community water charges and council water charges; mortgage interest payments; structural insurance premiums; ground rent and service charges.

Figure 7: Weekly regional median income before and after housing costs, financial year ending 2014 to financial year ending 2016, three-year average, by UK region

Source: Department for Work and Pensions, Households below Average Income.

Download this chart Figure 7: Weekly regional median income before and after housing costs, financial year ending 2014 to financial year ending 2016, three-year average, by UK region

Image .csv .xlsWeekly median income after housing costs was greatest in the South East and East of England over the three years to the financial year ending 2016 – £459 and £427 respectively. Therefore, the South East ranked first in terms of household disposable income per head in 2015 and second for equivalised median income for the financial year ending 2016. However, users should exercise caution when directly comparing these results – these measures of income don’t entirely overlap in terms of coverage and use different source data.

The North East and West Midlands had the lowest weekly median income after housing costs – £375 and £370 respectively.

Interestingly, median income before the deduction of housing costs in London was £524. This is a difference of 23% compared with median income after housing costs – the largest difference of all the UK regions. This clearly demonstrates the impact of high rents and other associated costs relating to dwellings, on economic well-being. On the other hand, Northern Ireland, Scotland and the East Midlands had the lowest difference between median incomes before and after housing costs over the three years to the financial year ending 2016.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Economic sentiment

It is important to consider sentiment, along with other measures of economic well-being, to improve our understanding of how changes in official measures of the economy are perceived by individuals. The Eurobarometer Consumer Survey, conducted by GFK on behalf of the European Commission, provides information regarding perceptions of the economic environment. The “Quality and methodology” section provides more information regarding the Eurobarometer Consumer Survey.

General economic situation and perception of financial situation

The Eurobarometer Consumer Survey asks consumers their views on the state of the general economic situation over the previous 12 months. A positive balance means that consumers perceived an improvement within the economy, a zero balance indicates no change and a negative balance indicates a perceived worsening.

Figure 8: Consumer perceptions of general economic situation and their own financial situation over last 12 months, January 2006 to June 2017

UK

Source: European Commission

Notes:

- The source is the Eurobarometer Consumer Survey, which is collected by GfK for the European Commission. Further information can be found in Quality and Methodology.

- A negative balance means that, on average, respondents reported the general economic situation. A positive balance means they reported it improved and a zero balance indicators no change.

Download this chart Figure 8: Consumer perceptions of general economic situation and their own financial situation over last 12 months, January 2006 to June 2017

Image .csv .xlsBetween Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2017 and Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017, the perception of the general economic situation declined from a balance of negative 21.8 to negative 27.5. This was the largest quarterly decline since Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2013. Analysis by GFK suggests that the worsening in the balance may have been caused by the pressure of both higher prices and slow wage growth, which are acting to dampen household spending. GFK also cite economic uncertainty abroad and later, in 2016, reduced confidence following the EU referendum. In the year following the EU referendum, consumers’ perception on the general economic situation has decreased by an average of 3.1 points per quarter.

The survey also asks respondents about their own financial situation. In Quarter 2 2017, the average aggregate balance was negative 2.3 – down from positive 1.2 in the previous quarter. This is the lowest level since Quarter 1 2015.

Perception of inflation

The Eurobarometer Consumer Survey also asks respondents about their perception of prices over the previous 12 months. A positive balance suggests that consumers perceive prices to have increased over the previous 12 months, while a negative balance suggests the opposite. In Quarter 2 2017, the balance increased to 24.3 from positive 20.8 in Quarter 1 2017, which was the highest value since October 2014.

Figure 9: Comparison between CPIH and individual's perception of price trends over the last 12 months, January 2006 to June 2017

UK

Source: European Commission

Notes:

- CPIH has been re-assessed to evaluate the extent to which it meets the professional standards set out in the Code of Practice for Official Statistics. The assessment report includes a number of requirements that need to be implemented for CPIH to regain its status as a National Statistic and we are working to address these.

- The source is the Eurobarometer Consumer Survey, which is collected by GfK for the European Commission. Further information can be found in Quality and Methodology.

- A negative balance means that, on average, respondents reported that the price level decreased. A positive balance means they reported it increased and a zero balance indicators no change.

Download this chart Figure 9: Comparison between CPIH and individual's perception of price trends over the last 12 months, January 2006 to June 2017

Image .csv .xlsSince November 2016, inflation expectations have been positive, corresponding with an increased Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) rate during this period. The 12-month rate was over 1.5% from November 2016 and has steadily increased to reach 2.6% in June 2017.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Economic well-being indicators already published

Between 2014 and 2015, the total net worth per head of the UK increased by 5.1%. The largest contribution was from the households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) sector. Estimates for 2016 are expected towards the end of 2017.

Between 2014 and 2015, household wealth per head increased by 3.3%, driven mainly by a 6.5% increase in the wealth in non-financial assets (for example, buildings and machinery). Estimates for 2016 are expected towards the end of 2017.

In June 2017, the CPIH inflation 12-month rate fell to 2.6% compared with 2.7% in May 2017. This was for the first fall in the inflation rate since April 2016 but still remains relatively high compared with recent years. The main reason was falling prices for motor fuels and certain recreational and cultural goods and services.

The unemployment rate in the three months to June 2017 fell to 4.5% from 4.6%. The employment rate (the proportion of people aged from 16 to 64 who were in work) was 75.1% in the three months to June 2017 – the highest rate since comparable records began in 1971.

The median UK household disposable income was £27,170 in the financial year ending 2017; this was £487 higher than the previous year and £1,466 higher than the pre-downturn value of £25,704 in the financial year ending 2008 – after accounting for inflation and household composition.

The wealthiest 10% of households owned 45% of aggregate total wealth in July 2012 to June 2014 and were 2.4 times wealthier than the second wealthiest 10%. Over the same period, the wealthiest 10% of households were 5.2 times wealthier than the bottom 50% of households (the bottom five deciles combined), who owned 9% of aggregate total wealth.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. Quality and methodology

Release policy

- The data used in this version of the release are the latest available at 29 September 2017. The UK resident population mid-year estimates used in this publication are those published on 23 June 2016. The latest population estimates published on 22 June 2017 are included in quarterly national accounts on 29 September 2017.

Basic quality and methodology information

Basic quality and methodology information for all indicators in this statistical bulletin can be found on our website:

- National accounts Quality and methodology Information report

- Consumer Prices Indices Quality and methodology Information report

- Wealth and Assets Survey Quality and methodology Information report

- Effects of taxes and benefits Quality and methodology information report

- Labour market Quality and methodology Information reports

These contain important information on:

- the strengths and limitations of the data and how it compares with related data

- users and uses of the data

- how the output was created

- the quality of the output including the accuracy of the data

Revisions and reliability

All data in this release will be subject to revision in accordance with the revisions policies of their original release. Estimates for the most recent quarters are provisional and are subject to revision in the light of updated source information. We currently provide an analysis of past revisions in statistical bulletins, which present time series. Details of the revisions are published in the original statistical bulletins.

Most revisions reflect either the adoption of new statistical techniques or the incorporation of new information, which allows the statistical error of previous estimates to be reduced.

Only rarely are there avoidable “errors”, such as human or system failures and such mistakes are made quite clear when they do occur.

For more information about the revisions policies for indicators in this release:

- National accounts revisions policy – covers indicators from the quarterly national accounts, UK Economic Accounts and the national balance sheet

- Wealth and Assets Survey revisions policy – covers indicators on the distribution of wealth

- Effects of taxes and benefits on household incomes revisions policy – covers indicators on the distribution of income

- Labour market statistics revisions policy – covers indicators from labour market statistics

- Consumer Price Inflation - revisions policy – covers indicators from consumer price indices

Our Revisions policies for economic statistics webpage is dedicated to revisions to economic statistics and brings together our work on revisions analysis, linking to articles, revisions policies and important documentation from the former Statistics Commission's report on revisions.

Data that come from the Eurobarometer Consumer Survey and Understanding Society releases are not subject to revision as all data are available at the time of the original release. These data will only be revised in light of methodological improvements or to correct errors. Any revisions will be made clear in this release.

Interpreting the Eurobarometer Consumer Survey

The Eurobarometer Consumer Survey, sourced from GFK on behalf of the European Commission, asks respondents a series of questions to determine their perceptions on a variety of factors, which collectively give an overall consumer confidence indicator. For each question, an aggregate balance is given, which ranges between negative 100 and positive 100.

Balances are the difference between positive and negative answering options, measured as percentage points of total answers. Values range from negative 100, when all respondents choose the negative option (or the most negative one in the case of five-option questions) to positive 100, when all respondents choose the positive (or the most positive) option.

The questions used in this release are:

Question 1: How has the financial situation of your household changed over the last 12 months? It has...

- got a lot better

- got a little better

- stayed the same

- got a little worse

- got a lot worse

- don’t know

Question 3: How do you think the general economic situation in the country has changed over the past 12 months? It has...

- got a lot better

- got a little better

- stayed the same

- got a little worse

- got a lot worse

- don’t know

Question 5: How do you think that consumer prices have developed over the last 12 months? They have...

- risen a lot

- risen moderately

- risen slightly

- stayed about the same

- fallen

- don’t know

Further information on this consumer survey is available from the Business and Consumer Survey section of the European Commission website.

Measuring national well-being

This article is published as part of our Measuring National Well-being programme. The programme aims to produce accepted and trusted measures of the well-being of the nation – how the UK as a whole is doing. Further information on Measuring National Well-being is available with a full list of well-being publications.