Cynnwys

- Main points

- Things you need to know about this release

- Total current healthcare expenditure in the UK

- Financing of healthcare

- International comparisons

- Total healthcare expenditure by function and provider

- Government healthcare expenditure

- Non-government healthcare expenditure

- Long-term care expenditure

- Preventive healthcare expenditure

- Appendix 1 – Revisions

- Appendix 2 – Data from the series: Expenditure on healthcare in the UK (1997 to 2016)

- References

- Authors and acknowledgments

- Quality and Methodology

1. Main points

Total current healthcare expenditure in 2016 was £191.7 billion, an increase of 3.6% on spending in 2015, when £185.0 billion was spent on healthcare in the UK.

Government-financed healthcare expenditure accounted for 79.4% of total spending, £152.2 billion.

Since 2013, government spending on curative and rehabilitative care in an inpatient setting has grown more slowly than curative and rehabilitative care delivered in outpatient, day case or home setting

Spending on health-related long-term care was £35.5 billion in 2016, with an additional £10.9 billion spent on long-term social care outside the health accounts definitions.

Government spending accounted for 62% of all spending on long-term care, with most other long-term care spending financed by out-of-pocket payments.

Total current healthcare expenditure in the UK was 9.8% of gross domestic product (GDP), higher than the median for OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) member states but second lowest of the seven nations in the G7, a position which has remained unchanged since UK health accounts were introduced for 2013

2. Things you need to know about this release

This bulletin contains data from the UK Health Accounts, providing figures for 2013 to 2016. Health accounts are a set of statistics analysing healthcare expenditure by three dimensions:

financing scheme – the source of funding for healthcare

function – the type of care and mode of provision

provider organisation – the type of healthcare provider in which care is carried out

The UK Health Accounts are produced according to the System of Health Accounts 2011 (SHA 2011), which provides internationally standardised definitions both for total current healthcare expenditure, and the analysis of this spending by financing scheme, function and provider organisation. The SHA 2011 definitions are used to measure healthcare expenditure from 2014 onwards by all EU member states and most other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) member states. Some OECD member states also produce healthcare expenditure statistics to SHA 2011 definitions for years before 2014, but the length of the back series produced to these definitions varies by country. The time series for UK Health Accounts runs back to 2013.

The definition of healthcare used in Health Accounts is somewhat broader than that used in other UK healthcare expenditure analyses (including our earlier Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK publication), and includes a number of services which are typically considered social care in the UK. More information about the definitions of health accounts and the differences between Health Accounts and other healthcare expenditure analyses is available in the Introduction to Health Accounts.

Health Accounts measure current expenditure on healthcare only. This means that spending on the formation and acquisition of capital items, such as buildings and vehicles, in any given year, are not included in the Health Accounts. However, the cost of the consumption of capital, a concept analogous to depreciation, is included in the Health Accounts figures. All figures contained in this article are for current expenditure only, with the exception of the appendix, which contains figures for current and capital expenditure produced using the definitions from our previous Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK analysis.

All figures in this article are reported in current prices; that is the price of goods or services at the time they were purchased, unadjusted for inflation.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Total current healthcare expenditure in the UK

Total current healthcare expenditure in the UK in 2016 was £191.7 billion. This accounted for 9.8% of gross domestic production (GDP), the same percentage as in 2015 . Both government and non-government spending on healthcare are included in this measure of healthcare expenditure.

Table 1: Healthcare Expenditure and Growth Rates in the UK, 2013 to 2016

| Expenditure (£ billions) | Government Expenditure (£ billions) | Non-government Expenditure (£ billions) | Total Expenditure Growth Rate (%) | Expenditure as % of GDP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 171.3 | 136.0 | 35.2 | 9.8% | |

| 2014 | 178.6 | 142.0 | 36.6 | 4.3% | 9.7% |

| 2015 | 185.0 | 146.9 | 38.0 | 3.5% | 9.8% |

| 2016 | 191.7 | 152.2 | 39.5 | 3.6% | 9.8% |

| Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) |

Download this table Table 1: Healthcare Expenditure and Growth Rates in the UK, 2013 to 2016

.xls (27.6 kB)Notes for: Total current healthcare expenditure in the UK

- Growth rates for each year are given as the growth between the stated year and previous year. For example, the growth figure for 2015 is the growth measured between 2014 and 2015.

4. Financing of healthcare

Government expenditure accounted for 79.4% of all current healthcare expenditure in 2016

Government expenditure on healthcare, which includes spending by the NHS, local authorities and other public providers of healthcare, was £152.2 billion, accounting for 79.4% of total current healthcare expenditure. There are five further financing schemes used to analyse healthcare expenditure in the UK within the health accounts system. These are:

compulsory insurance schemes – covering the healthcare elements of motor insurance and employers’ liability insurance

voluntary health insurance schemes – covering other healthcare insurance such as private medical and dental insurance, employer self-insurance schemes, health cash plans, dental capitation plans and the healthcare element of travel insurance

NPISH (non-profit institutions serving households) financing schemes – covering charity expenditure funded through voluntary donations, grants and investment income, excluding charity expenditure funded through client contributions (classed as out-of-pocket expenditure in health accounts) and purchases of care by public and NHS bodies (classed as government expenditure in health accounts)

enterprise financing schemes – covering healthcare activity funded by organisations (primarily employers) outside of an insurance scheme, such as occupational healthcare

out-of-pocket expenditure – covering non–insurance spending on healthcare goods and services, including client contributions for local authority and NHS provided services and prescription charges

More information on these schemes can be found in An introduction to health accounts and UK Health Accounts: methodological guidance

15.1% of overall spending was funded out-of-pocket

The largest of the non-government financing schemes in 2016 was out-of-pocket expenditure, which accounted for £29.0 billion or 15.1% of overall spending, followed by voluntary health insurance, accounting for 3.3% of overall spending or £6.2 billion. The final three categories of financing schemes: NPISH, enterprise financing and compulsory insurance accounted for 1.6%, 0.5% and 0.1% of total healthcare expenditure in 2016, respectively.

Figure 1: Total current healthcare expenditure by financing scheme, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 1: Total current healthcare expenditure by financing scheme, 2016

Image .csv .xls

Table 2: Growth in total current healthcare expenditure by financing scheme in the UK, 2014 to 2016

| growth rate (%) | Average annual growth rate 2013 to 2016 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financing scheme | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Government-financed expenditure | 4.4% | 3.5% | 3.6% | 3.8% |

| Compulsory private insurance schemes | -2.3% | -3.9% | 1.4% | -1.6% |

| Voluntary health insurance schemes | 3.5% | -1.3% | -0.9% | 0.4% |

| Non-profit institutions serving households financing schemes | 7.0% | 6.6% | 4.3% | 6.0% |

| Enterprise financing schemes | 1.2% | 0.9% | 4.0% | 2.0% |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure | 4.0% | 4.9% | 4.9% | 4.6% |

| Total | 4.3% | 3.5% | 3.6% | 3.8% |

| Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) | ||||

Download this table Table 2: Growth in total current healthcare expenditure by financing scheme in the UK, 2014 to 2016

.xls (28.7 kB)Expenditure in all financing schemes grew in 2016, with the exception of voluntary insurance . Further information on the government financing scheme can be found in Section 7 and further information on the other financing schemes in Section 8.

Figure 2: Healthcare spending per person, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 2: Healthcare spending per person, 2016

Image .csv .xls£2,920 was spent on healthcare per person in the UK in 2016 across all financing schemes.

Notes for: Financing of healthcare

UK Health Accounts: 2015 reported healthcare expenditure of 9.9% of GDP in 2015. However, due to regular revisions to the GDP figures, which have resulted in GDP for 2015 being revised upwards, the estimate for healthcare expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 2015 has been revised to 9.8% in this publication.

Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Growth rates for each year are given as the growth between the stated year and previous year. For example, the growth figure for 2015 is the growth measured between 2014 and 2015.

Average growth rates for cumulative growth across multiple years are geometric means

It should be noted that the change in voluntary insurance between 2015 and 2016 may have been affected due to changes in the reporting of reinsurance resulting from the introduction of the Solvency II Directive on insurance reserves. More information can be found in Section 8: non-government expenditure.

5. International comparisons

The UK spends a greater proportion of GDP on healthcare than the OECD median

Healthcare expenditure constituted 9.8% of the UK’s GDP in 2016. Although 2016 health spending data is unavailable for other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states, forecasts are published by the OECD, based on 2015 data and projected growth rates. When compared to projected expenditure, the proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) that the UK spent on healthcare is above the median for OECD countries.

Figure 3: Healthcare expenditure as percentage of GDP for OECD member states, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

- Australian expenditure estimates exclude all expenditure on residential aged care facilities in welfare (social) services

Download this chart Figure 3: Healthcare expenditure as percentage of GDP for OECD member states, 2016

Image .csv .xlsOf the G7 nations (a group of large developed economies), the UK had the second to lowest proportion of GDP spent on healthcare, higher only than Italy which spent 8.9% of its GDP on healthcare. The US spent the most on healthcare as a percentage of GDP (17.2%). Since 2013, the first year for which we have comparable data, the UK has consistently been the second lowest of the G7 nations.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Total healthcare expenditure by function and provider

Curative and rehabilitative spending accounted for 40.4% of total current healthcare expenditure

In 2016, the largest category of spending within the Health Accounts, by function and provider, was curative and rehabilitative spending in hospitals, which accounted for 40.4% of total expenditure on healthcare in the UK.

Curative and rehabilitative covers care administered for which the principle purpose is to relieve symptoms, reduce the severity of an illness or prevent complication of illnesses (curative) or care which is intended to stabilise or improve impaired body functions, compensate for loss of such functions or improve a patient’s ability to participate in everyday life (rehabilitative). Hospital settings include general, mental health and specialised hospitals.

This category of function and provider was the largest component for government-financed expenditure, as well as compulsory and voluntary insurance schemes, while further expenditure in this category was funded by out-of-pocket spending and through NPISH (non-profit institutions serving households) financing. The second-largest category of spending by function and provider in 2016 was on curative and rehabilitative care in ambulatory settings, which accounted for 16.2% of total healthcare expenditure. This function-by-provider category was the second-largest for both government financed expenditure and out-of-pocket expenditure. Ambulatory settings include general medical practices, dental practices and other healthcare practitioners (such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists), and the curative and rehabilitative care provided by ambulatory providers was predominantly in an outpatient setting, although some care was also provided at home.

For further information on what services are contained in other categories see the 2016 Methods Paper and Introduction to the Health Accounts.

Table 3: Total Healthcare Expenditure in each 'function by provider' category, 2016

| United Kingdom, 2016 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| per cent | |||||||||

| Hospitals | Residential long-term care facilities | Ambulatory providers | Providers of ancillary services | Providers of medical goods | Providers of preventive care | Providers of healthcare system administration and financing | Rest of economy and rest of world | Healthcare not elsewhere classified | |

| Curative/rehabilitative care | 77.5 | 0.1 | 31.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Long-term care | 1.1 | 22.4 | 9.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.0 |

| Ancillary services | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Medical goods | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 20.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 0.0 |

| Preventive care | 1.0 | 0.0 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Governance, and health system and financing administration | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Healthcare not elsewhere classified | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) | |||||||||

| Notes: | |||||||||

| The medical goods function includes pharmaceuticals dispensed outside of a hospital setting. It excludes pharmaceuticals and other products used as part of a wider course of treatment, which are included in the costs of that treatment. For example, drugs consumed by a patient as part of an inpatient hospital episode would be included in the expenditure on hospital inpatients. | |||||||||

Download this table Table 3: Total Healthcare Expenditure in each 'function by provider' category, 2016

.xls (37.4 kB)7. Government healthcare expenditure

Government spending continues to fund the majority of healthcare expenditure in the UK.

Government financing by function

Figure 4 and 5 shows how government healthcare expenditure was split between the functional categories of Health Accounts.

Figure 4: Government healthcare expenditure by healthcare function, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 4: Government healthcare expenditure by healthcare function, 2016

Image .csv .xls

Figure 5: Government healthcare expenditure by healthcare function, 2013

UK 2013

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

- Percentage symbol was added after the release went live at 1:10pm on 25 April 2018.

Download this chart Figure 5: Government healthcare expenditure by healthcare function, 2013

Image .csv .xlsThe largest function category of government spending was curative and rehabilitative care, which accounted for 63.9% of government spending in 2016.

Government-funded long-term care (health), which includes health-related social care spending by local authorities and Carer’s Allowance , as well as NHS continuing care and palliative care services, was the second-largest functional category for government spending, with £23.6 billion spent in 2016.

Spending on medical goods (including pharmaceuticals) was the third-largest category of government spending and made up £16.0 billion of government healthcare expenditure in 2016. This function of healthcare includes pharmaceuticals purchased or dispensed outside of hospital settings and other medical goods, such as glasses and hearing aids. In 2016, a majority of this expenditure was spent on pharmaceutical and other non-durable medical goods, and provided by specialist retailers of medical goods such as pharmacies. It should be noted that the medical goods function excludes pharmaceuticals and other products used as part of a wider course of treatment, which are included in the costs of that treatment. For example, drugs consumed by a patient as part of an inpatient hospital episode will be included in the expenditure on hospital inpatients.

Curative care’s share of government healthcare funding increased between 2013 and 2016

Figure 5 shows that curative and rehabilitative care grew at a faster rate than most other categories of government spending between 2013 and 2016. This resulted in its share of government healthcare spending increasing from 63.0% to 63.9%. The growing share of curative and rehabilitative care has displaced the proportion of healthcare expenditure made up of several other functions, including long-term care (health) which fell from 15.7% to 15.5%, and medical goods which fell from 10.8% to 10.5%.

Expenditure on governance and health system administration was the only functional category to see a fall in expenditure between 2013 and 2016, from £2.3bn to £2.1bn. This spending covers central functions such as the strategic governance of the healthcare system and setting and monitoring standards of care, but does not cover the commissioning, legal, procurement or other overhead costs of the NHS, which are included in the cost of care. There was a corresponding fall in governance and health system administration as a share of government healthcare expenditure from 1.7% in 2013 to 1.4% in 2016.

In 2016, long-term health care was the fastest growing function for government-financed expenditure

Figure 6 shows the long-term care (health) was the fastest growing function of government healthcare expenditure in 2016, while governance and health system administration was the only one of the six main functions to fall.

Figure 6: Growth rates in functions of government, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 6: Growth rates in functions of government, 2016

Image .csv .xlsThe health accounts divide curative and rehabilitative care, which is the largest component of government expenditure on healthcare in the UK, into four “modes of provision”: inpatient care, day care (including day case admissions), outpatient care and home-based care. The growth rates for each category can be seen in Table 4.

Government expenditure on curative and rehabilitative care by mode of provision

Table 4: Growth in government-financed curative and rehabilitative care sub-categories in the UK, 2013 to 2016

| Government financed | Growth rates (%) | Expenditure (£ billions) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Average annual growth 2013 to 2016 | 2016 |

| All curative and rehabilitative care | 3.9% | 5.9% | 4.2% | 4.3% | 97.3 |

| Inpatient | 3.7% | 4.3% | 2.9% | 3.6% | 42.1 |

| Day | 5.0% | 5.9% | 4.8% | 5.6% | 8.3 |

| Outpatient | 3.8% | 7.2% | 5.3% | 4.7% | 41.9 |

| Home-Based | 4.8% | 6.8% | 5.2% | 5.5% | 5.0 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) | |||||

Download this table Table 4: Growth in government-financed curative and rehabilitative care sub-categories in the UK, 2013 to 2016

.xls (28.7 kB)In 2016, the slowest growing mode of provision was inpatient care, continuing a trend observed in previous years. Faster growth in the categories of day, outpatient and home-based care can be seen in the context of the drive for more efficient forms of healthcare provision being substituted for more expensive inpatient stays.

Relationship of health spending to activity

When analysing trends in the mode of provision used for delivering care, looking at activity data can also be informative.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report the proportion of selected treatments carried out without an overnight stay as a measure of efficiency (Health at a Glance 2017), with the UK reporting lower incidences of overnight hospital stays following cataract surgery and tonsillectomies than the OECD average. Internationally, the number of surgical procedures carried out as day case treatments has been increasing, in part due to innovations in less intrusive surgery techniques and better anaesthetics.

Hospital expenditure makes up nearly three-quarters of government curative and rehabilitative care spending. Table 5 shows how the number of elective procedures carried out in NHS hospitals as day cases has grown between 2013 and 2016, while the number of elective procedures carried out with an overnight stay has fallen. However, inpatient admission growth was increased by non-elective admissions, particularly in 2016, when growth in non-elective admissions also exceeded that of day cases.

Whilst these data are not a complete picture of activity by mode of provision, they show the shift in activity away from treatment requiring overnight admission to procedures that allow patients to leave on the same day as arrival.

Table 5: Growth in NHS hospital activity between 2013 and 2016 by type of admission

| Growth rates (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission Type | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Elective inpatient | -0.5% | -3.0% | -1.3% |

| Elective day case | 4.5% | 4.7% | 2.6% |

| Non-elective | 3.5% | 1.2% | 4.2% |

| Outpatient | 3.5% | 2.9% | 3.2% |

| Total | 3.5% | 2.4% | 2.8% |

| Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) | |||

Download this table Table 5: Growth in NHS hospital activity between 2013 and 2016 by type of admission

.xls (27.1 kB)We also produce estimates for the quantity of healthcare outputs delivered across the health service for the UK, including activity outside of hospitals, such as community services, primary care services and prescribing. These statistics weight the growth rates of thousands of different types of activity across the health service by their cost, to give an estimate for the change in the quantity of healthcare provided. Thus, the quantity output figures are not affected by the rate of cost inflation experienced by providers. These figures estimate growth in cost-weighted output across UK public service healthcare of 4.2% in 2015, the latest year available.

In terms of the human resources available in the NHS, workforce statistics for England, show NHS full-time equivalent staff numbers increased by about 6% between 2013 and 2016 from approximately 974,000 to approximately 1,032,000. These numbers include both professionally qualified clinical staff and other staff employed in the English NHS, with much of the increase in staff numbers over this period coming from support staff, although nursing and medical staff numbers also grew.

By combining the cost-weighted output measure with the quantity of staff and other inputs used in the NHS, ONS public service productivity statistics provide insight into changes in the productivity of the health service and more information can be found in Public service productivity estimates: healthcare.

Government expenditure by provider

The UK Health Accounts also analyse government expenditure by type of provider organisation.

The below table show that in 2016, the provider type which made up the largest share of government-funded healthcare was hospitals, which accounted for £73.8 billion of spending, 48.5% of total government healthcare expenditure.

Figure 7: Government expenditure by provider type, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 7: Government expenditure by provider type, 2016

Image .csv .xlsProviders of ambulatory healthcare services accounted for 24.6%, or £37.8 billion, of government healthcare expenditure. Providers of medical goods, which include pharmacies, accounted for the third-largest share of government expenditure – 10.3%, and residential long-term care facilities the fourth largest, accounting for 7.9% of government expenditure. These four provider types accounted for 91.3% of all government spending on healthcare in the UK.

Government expenditure on dental practices grew less than other ambulatory healthcare providers

Health Accounts break down ambulatory providers by four sub-categories:

offices of general medical practitioners

dental practices

providers of home healthcare services, which include home care services provided by local authorities and specialist independent sector providers

other ambulatory providers, including paramedical practitioners (such as occupational therapists and physiotherapists) and community healthcare services

Table 6: Government spending on ambulatory providers of healthcare, 2016

| Government Expenditure (£ billions) | 2016 | Average annual growth rate 2013 to 2016 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP 3.1.1 General Medical Practices | 12.9 | 5.4% | 4.1% | ||

| HP 3.2 Dental Practices | 2.9 | 3.2% | 0.5% | ||

| HP 3.5 Providers of home health care provision | 8.6 | 4.5% | 5.4% | ||

| HP 3.x Other ambulatory providers | 13.5 | 4.6% | 4.6% | ||

| Total | 37.8 | 4.7% | 4.3% | ||

| Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) |

Download this table Table 6: Government spending on ambulatory providers of healthcare, 2016

.xls (27.6 kB)Table 6 shows government expenditure on the four subcategories of ambulatory providers in 2016. In 2016, government expenditure grew faster in general medical practices than other categories of ambulatory providers, while the growth of government expenditure on dental practices has been consistently lower than the other categories of ambulatory providers since 2013.

Experimental general practice workforce data for England show a slight fall of 0.3% in full-time equivalent general practitioners (GPs) between September 2015 and September 2016. However, full-time equivalent numbers for support staff in general practice, including practice nurses, direct patient care staff and administrative staff, grew by 3.3% between September 2015 and September 2016, faster than the overall staff growth for the English NHS over the same period.

Government expenditure by function and provider

The health accounts can also break down expenditure by a combination of functions and providers of healthcare. The table below lists the 10 largest “function by provider” categories within government expenditure on healthcare.

Figure 8: Ten largest government-financed expenditure by function and provider, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

- Figures may not sum due to rounding

Download this chart Figure 8: Ten largest government-financed expenditure by function and provider, 2016

Image .csv .xlsTaken as a whole, these 10 “function by provider” categories constitute almost 96% of all government healthcare expenditure in 2016. Curative and rehabilitative care delivered in hospitals represented 47.1% of all government healthcare expenditure in 2016, more than double the second-largest category of curative and rehabilitative care provided by ambulatory services (16.4%).

Note for: Government healthcare expenditure

The medical goods function includes pharmaceuticals dispensed outside of a hospital setting. It excludes pharmaceuticals and other products used as part of a wider course of treatment, which are included in the costs of that treatment. For example, drugs consumed by a patient as part of an inpatient hospital episode would be included in the expenditure on hospital inpatients.

Carer’s Allowance is included in the health accounts, as it constitutes expenditure by government on funding household provision of long-term care, consistent with the SHA 2011 guidelines

Growth rates for each year are given as the growth between the stated year and previous year. For example, the growth figure for 2015 is the growth measured between 2014 and 2015

Average growth rates for cumulative growth across multiple years are geometric means

Growth rates for each year are given as the growth between the stated year and previous year. For example, the growth figure for 2015 is the growth measured between 2014 and 2015.

Average growth rates for cumulative growth across multiple years are geometric means

Growth rates for each year are given as the growth between the stated year and previous year. For example, the growth figure for 2015 is the growth measured between 2014 and 2015.

8. Non-government healthcare expenditure

Out-of-pocket was the largest non-governmental source of financing in 2016

In 2016, a total of £39.5 billion spent on healthcare expenditure in the UK was financed through non-government schemes. The non-government schemes were compulsory insurance, voluntary insurance, non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH), enterprise financing and out-of-pocket expenditure. Of these non-governmental sources of healthcare spending, out-of-pocket spending was the largest in 2016, constituting £29.0 billion, or 15.1% of total healthcare expenditure in that year.

Non-government expenditure by function

Curative and rehabilitative care less dominant for non-government spending than for government spending

Curative and rehabilitative care less dominant for non-government spending than for government spending The table below shows how non-government healthcare expenditure was split between the health accounts’ functional categories. As with government-funded expenditure, the largest functional categories for non-government healthcare expenditure were curative and rehabilitative care, followed by long-term care (health) and medical goods spending. However, the share of spending on curative and rehabilitative care was far less dominant for non-government spending, accounting for 31.3%, relative to 63.9% for government expenditure.

Figure 9: Non-government financed expenditure by functional category, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics, LaingBuisson, Association of British Insurers

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation 2.Figures may not sum due to rounding

Download this chart Figure 9: Non-government financed expenditure by functional category, 2016

Image .csv .xls

Figure 10: Non-government financed expenditure by provider category, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics, LaingBuisson, Association of British Insurers

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

- Figures may not sum due to rounding

Download this chart Figure 10: Non-government financed expenditure by provider category, 2016

Image .csv .xlsLargest provider category for non-government spending was residential long-term care facilities

Figure 9 shows the variation in provision of healthcare by different financing schemes. This breakdown follows a similar pattern to 2015, with healthcare provided in residential long-term care facilities accounting for over one quarter of non-government-financed healthcare expenditure. Other large providers of healthcare funded by non-government sources were providers of ambulatory healthcare, such as homecare providers and dental practices, hospitals and retailers of medical goods, such as pharmacists.

Long-term healthcare overtook medical goods as largest healthcare function for out-of-pocket spending

Out-of-pocket expenditure, the largest non-government financing scheme, was a source of financing across a range of settings. The largest provider type for out-of-pocket spending was residential long-term care facilities, such as care homes, while the second largest was providers of ambulatory healthcare, with dental practices the largest subcategory of this provider type.

In 2016, the largest functional category of out-of-pocket spending was on long-term care (health), for the first time in the series, with medical goods accounting for the largest function in previous years. Out-of-pocket spending on long-term care (health) expenditure was £10.7 billion in 2016, covering both private purchases of care and client contributions to local authority care. Medical goods (which includes pharmaceuticals) was the second-largest function, with provision of medical goods split between specialist retailers of medical goods, such as pharmacies and opticians, and non-specialist retailers, which are categorised as rest of economy providers.

Small fall in voluntary insurance spending in 2016

Voluntary insurance was the third-largest financing scheme of healthcare expenditure in the United Kingdom in 2016, with these schemes funding £6.2 billion of healthcare spending, a fall of 0.9% on 2015. This fall occurred despite increases in the standard rate of Insurance Premium Tax from 6% to 9.5% in November 2015 and again to 10% in October 2016, and a slight increase in insurer’s expenditure on claims. It should be noted that the fall in voluntary health insurance in 2016 may have been affected by changes to the reporting of reinsurance in data we use from the ABI (Association of British Insurers). Reinsurance is insurance purchased by insurers to protect against losses, and was affected by the Solvency II Directive which took effect in January 2016.

This was the second year of falling expenditure on voluntary health insurance, as spending through this financing scheme also fell in 2015, driven by a fall in interest earned on insurance reserves.

NPISH financing accounted for £3.1 billion of healthcare expenditure in 2016. 56.4% of NPISH expenditure on healthcare was funded through domestic charitable income sources, such as donations and investment income, while 43.0% was derived from government grants. It should be noted that while spending by charitable organisations funded by government grants was classified as NPISH financing, purchases of care from charities by health bodies and local authorities are not recorded as NPISH spending, and are instead included in government expenditure. Likewise, while charity expenditure funded by donations from individuals is included in the NPISH figure, purchases of care by patients are categorised as out-of-pocket expenditure.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. Long-term care expenditure

The long-term care category covers care services aimed at reducing suffering and managing chronic health conditions (including old-age and disability-related conditions), where an improvement in health is not expected.

The long-term care category is split into a health-related care element that is included in the measure of total current health expenditure in health accounts and a social element relating to assistance-based services, which sits outside the health accounts. Services included within total current healthcare expenditure, in the long-term care (health) category, include care where a substantial proportion of the service involves support with basic activities of daily living (ADLs), which include things such as bathing, dressing and walking. Long-term care (social), which is not included in the definition of total current healthcare expenditure, covers services where care predominantly consists of support with instrumental activities of daily life (IADLs), which include things such as shopping, cooking and managing finances.

Total long-term care expenditure in 2016 was £46.4 billion, with a growth rate of 5.0%. Demographic changes in the UK, such as an ageing and expanding population has led to an increase in the number of people with complex social care and healthcare needs. Efforts have been made to integrate health and social care services to manage the delivery of services to people. In England legislation such as the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the Care Act 2014 sets out obligations for the health system to make it easier for health and social care services to work together. This has resulted in the establishment of programmes such as the Better Care Fund which encourages greater collaboration between NHS and local authorities through pooled budget arrangements and integrated spending plans.

Furthering this trend to greater integration of health and social care, Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships were started in 2016 with the aim of promoting co-operation between NHS and local authorities for 44 geographical “footprints”. Ten of the Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships are to evolve into the first set of Integrated Care Systems in 2018, with NHS and local authorities taking collective responsibility for managing budgets and delivering services. Health and social care integration has also developed in the devolved administrations of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Figure 11: Total expenditure on long-term care in the UK, 2016

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics, LaingBuisson, Association of British Insurers

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 11: Total expenditure on long-term care in the UK, 2016

Image .csv .xlsAs Figure 11 shows, in 2016 total spending on long-term care (health) activities was £35.5 billion, while £10.9 billion was spent on long-term care for social needs.

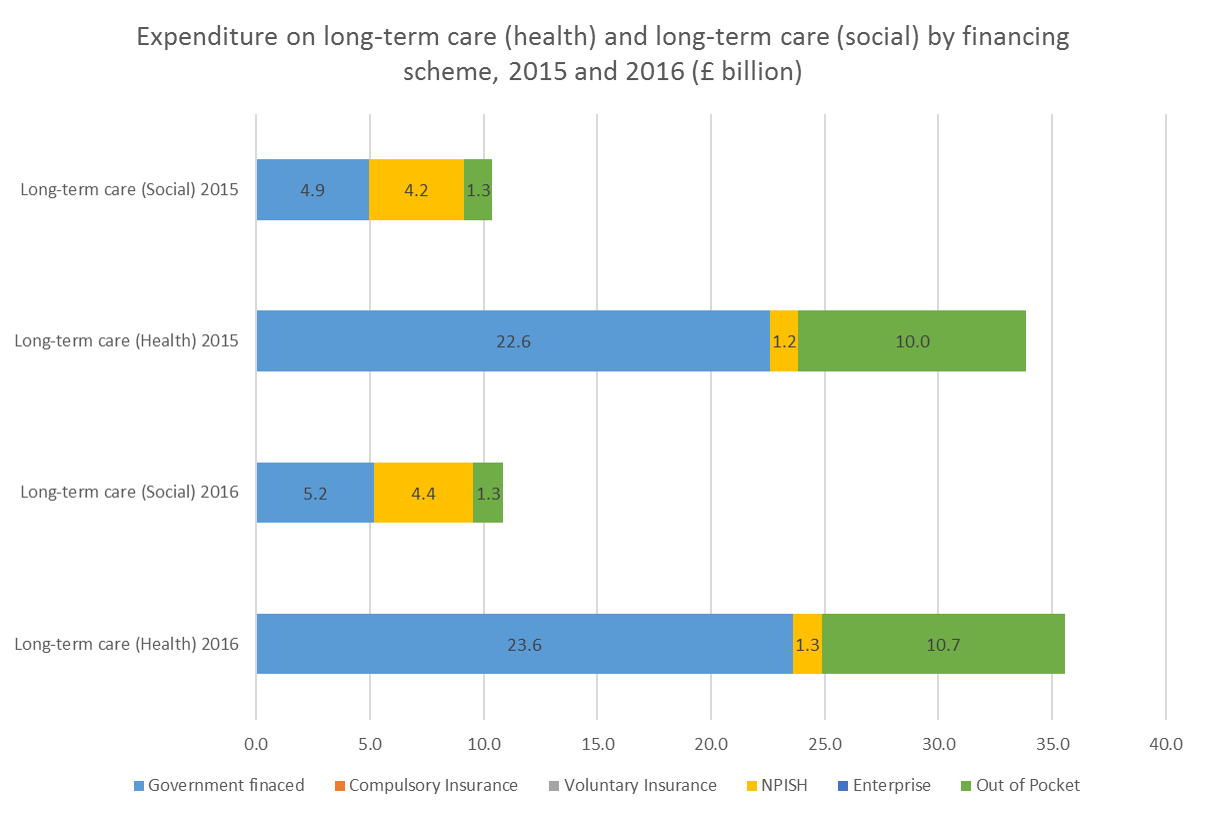

Figure 12: Expenditure on long-term care (health) and long-term care (social) by financing scheme, 2015 and 2016

UK 2015, 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics, LaingBuisson

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this image Figure 12: Expenditure on long-term care (health) and long-term care (social) by financing scheme, 2015 and 2016

.png (51.4 kB) .xlsx (16.1 kB)Figure 12 shows how long-term care (health) was split by financing scheme. In 2016, government expenditure on long-term care (health) was £23.6 billion, accounting for 66.4% of total long-term care (health) spending, while out-of-pocket expenditure accounted for a further 30.0%. Spending by non-profit institutions serving households (NPISHs) accounted for the final 3.6% of long-term care (health) financing.

Spending financed through NPISH sources, primarily charity spending funded by donations, grants and investment income, accounted for a larger share of long-term care (social) of 40.1%, while government expenditure remained the largest source of funding at 47.6%.

Out-of-pocket expenditure on total long-term care grew at 6.8% in 2016, faster than government expenditure, which grew at 4.4%, a similar rate to NPISH expenditure. Out-of-pocket expenditure was the fastest growing form of finance for both long-term care (health) and long-term care (social).

As with curative and rehabilitative care, long-term care (health) can be split by mode of provision, with inpatient care, consisting of residential and nursing care and home-based care being the two main modes. Total expenditure on these two categories was £23.4 billion and £11.9 billion respectively in 2016, with spending on inpatient long-term care (health) growing at 4.8% and spending on home-based long-term care (health) growing at 5.9% in 20163.

Notes for:Long-term care expenditure

Long-term care (social) is not included in the health accounts measure of total current healthcare expenditure

Due to changes in the main data source used for local authority adult social care expenditure in England between the finance year ending 2014 and financial year ending 2015, consistent comparisons between the relative growth of inpatient and home based long-term care (health) are not possible or the years between 2013 and 2015.

10. Preventive healthcare expenditure

Government spending funded about three-quarters of total preventive care spending in 2016

In 2016, spending on preventive healthcare was £10.3 billion. This was an increase of 5.3% on spending in 2015, when total expenditure on preventive healthcare was £9.8 billion.

Government expenditure was the predominant mode of financing for preventive healthcare accounting for 75.8% of total preventive care spending, or £7.8 billion in 2016. A further £1.3 billion was financed through out-of-pocket expenditure, with £0.8 billion spent through enterprise financing, primarily on occupational healthcare and hospital screening. Voluntary insurance accounted for £0.2 billion, which was mainly preventive dental activity such as check-ups and hygienist visits funded through dental capitation schemes.

Figure 13: Expenditure on preventive care in the UK, by financing scheme, 2016

Government spending was the dominant source of funding for preventive healthcare in the UK in 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics, LaingBuisson

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 13: Expenditure on preventive care in the UK, by financing scheme, 2016

Image .csv .xls

Figure 14: Share of total preventive care spending by preventive category, 2016'

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics, LaingBuisson

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

- Excludes spending on "preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes", which is not distinguishable from other sub-categories.

- Figures may not sum due to rounding

Download this chart Figure 14: Share of total preventive care spending by preventive category, 2016'

Image .csv .xlsFigure 14 shows the components of preventive care expenditure in 2016. Healthy condition monitoring programmes was the largest category of expenditure, accounting for 49.0% of preventive healthcare spending, and this category also accounted for most of the increase in preventive spending across government, out-of-pocket and enterprise financing schemes in 2016. As Figure 15 shows, healthy condition monitoring programmes increased their share of total preventive spending expenditure from 47.0% in 2015. The proportion of preventive care expenditure spent on information, education and counselling programmes fell from 32.6% in 2015 to 30.8% in 2016.

Figure 15: Share of total preventive care spending by preventive category, 2015

UK 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics, LaingBuisson

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

- Excludes spending on "preparing for disaster and emergency response programmes", which is not distinguishable from other sub-categories.

- Figures may not sum due to rounding

Download this chart Figure 15: Share of total preventive care spending by preventive category, 2015

Image .csv .xls11. Appendix 1 – Revisions

Overall, revisions to the UK Health Accounts series for 2013, 2014 and 2015 have resulted in some changes in total current healthcare expenditure of no more than 0.1% for any one year. The changes have led to total expenditure on healthcare falling slightly in 2013 and 2014, mainly because of revisions made to data sources used to calculate total government expenditure and expenditure on consumer medical items. Revisions in source data have also resulted in small revisions to voluntary insurance and out of pocket expenditure.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys12. Appendix 2 – Data from the series: Expenditure on healthcare in the UK (1997 to 2016)

Figure 14 shows the growth of current and capital healthcare expenditure between 1997 and 2016. It uses a previous data series we produce, Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK. These figures differ from health accounts and exclude local authority spending on long-term care. Information on how the data in Figure 16 differ from the Health Accounts can be found in the Introduction to Health Accounts.

Between 1997 and 2016 total healthcare expenditure increased from £54.5 billion to £170.6 billion. It grew at an average annual rate of 6.2%. Of total healthcare expenditure in 2016, £165.4 billion was spent on current expenditure and the remaining £5.2 billion was capital expenditure.

Figure 16: Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK by current and capital expenditure, 1997 to 2016

UK 1997 to 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 16: Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK by current and capital expenditure, 1997 to 2016

Image .csv .xlsFigure 15 shows the split between public and private current expenditure from the Expenditure on healthcare in the UK data series. Current public expenditure on healthcare increased from £41.6 billion in 1997 to £135.5 billion in 2016. Current private expenditure spending consists of a number of components, including private households, private medical insurance and third sector spending such as charities, and increased from £10.2 billion in 1997 to £29.9 billion in 2016.

Figure 17: Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK by current public and private expenditure, 1997 to 2016

UK 1997 to 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation

Download this chart Figure 17: Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK by current public and private expenditure, 1997 to 2016

Image .csv .xlsEach year the data from the Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK series are revised, due to revisions made to the national accounts, primarily for private healthcare expenditure. Overall, the revisions to this series between this year’s figures and 2015’s figures have resulted in changes to total healthcare expenditure of no more than 1% for any given year. These revisions are available in the datasets accompanying this release.

Reconciliation between UK Health Accounts and Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK

Table 8 shows the differences between the healthcare expenditure total from the UK Health Accounts series and Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK along with these changes as a percentage of the UK’s gross domestic product in 2016.

Table 7: Reconciliation of Health accounts and expenditure on healthcare in the UK reconciliation, 2016

| United Kingdom, 2016 | £ billions | % of GDP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK" | 170.6 | 8.7% | |

| Capital expenditure2 | -5.2 | -0.3% | |

| Changes to government expenditure: | |||

| Addition of healthcare services provided by government bodies other than health departments3 | 0.4 | 0.0% | |

| Addition of health-related social care4 | 13.4 | 0.7% | |

| Addition of Carer's Allowance5 | 2.8 | 0.1% | |

| Other changes to government expenditure6 | 0.0 | 0.0% | |

| Changes to out-of-pocket expenditure: | |||

| Transfer of health insurance claims from out-of-pocket expenditure to insurance expenditure | -3.0 | -0.2% | |

| Addition of long-term care (health) | 10.7 | 0.5% | |

| Other changes to out-of-pocket expenditure7 | -0.4 | 0.0% | |

| Changes to voluntary health insurance expenditure: | |||

| Transfer of health insurance claims from out-of-pocket expenditure to insurance expenditure | 3.0 | 0.2% | |

| Other changes to insurance expenditure8 | 0.8 | 0.0% | |

| Changes to other financing schemes: | |||

| Changes to expenditure by NPISH9 | -2.6 | -0.1% | |

| Addition of compulsory insurance10 | 0.3 | 0.0% | |

| Addition of enterprise financing11 | 0.9 | 0.0% | |

| UK health accounts | 191.7 | 9.8% | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) | |||

| Notes: | |||

| 1. The pre-existing healthcare expenditure series published by ONS. | |||

| 2. Capital spending is not included in the health accounts, which is a measure of current healthcare expenditure. | |||

| 3. Net addition of providers of preventive care and services provided by government bodies whose purpose is not primarily to provide healthcare (e.g. Health and Safety Executive, police healthcare spending, etc). | |||

| 4. Health-related elements of social care spending are included in health accounts but not part of the "Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK" series. | |||

| 5. State welfare payments to carers looking after someone with significant personal care needs are included in long-term care in the SHA 2011 definitions, but not in "Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK". | |||

| 6. Includes revisions to the measurement of education and training, and research and development expenditure deducted from health accounts. | |||

| 7. Includes data source changes. | |||

| 8. Includes the addition of employer self-insurance schemes (where the employer assumes the risks associated with cover), dental capitation plans, the healthcare element of travel insurance and Insurance Premium Tax on eligible products, and the removal of accident insurance. | |||

| 9. Whereas the third sector in the “Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK” series included all charity healthcare spending, health accounts include only spending funded through NPISH sources – voluntary donations, grants and investment income, excluding charity expenditure funded through client contributions and purchases of care. | |||

| 10 .Compulsory insurance schemes were not part of "Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK". | |||

| 11. Enterprise financing schemes were not part of "Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK". | |||

| 12. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | |||

| 13. All figures are provided in current prices, unadjusted for inflation. | |||

Download this table Table 7: Reconciliation of Health accounts and expenditure on healthcare in the UK reconciliation, 2016

.xls (37.4 kB)Significant elements of expenditure included in Health Accounts are excluded from the Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK series, and the reverse also holds true. Capital expenditure is not included in the Health Accounts and thus £5.2 billion of capital expenditure recorded in the 2016 Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK is removed. In addition, expenditure by non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) only covers expenditure financed by donations, grants and investment income and not expenditure financed by sales and charges. As a result of this, the Health Accounts NPISH expenditure is £2.6 billion less than the Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK figure.

The largest additions to healthcare expenditure recorded by Health Accounts is the inclusion of health-related long-term care. This accounts for an additional £26.9 billion, which can be broken down into £13.4 billion spent on government-financed health-related social care, £2.8 billion spent on Carer’s Allowance and £10.7 billion spent of long-term care (health) from out-of-pocket spending.

Compulsory insurance and enterprise financing schemes do not form part of the Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK series and these two financing schemes are also added to reconcile the Health Accounts total expenditure with the Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK total expenditure.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys13. References

NHS Digital, NHS Workforce Statistics

NHS England, Monthly Hospital Activity Statistics

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Eurostat, World Health Organisation (2011), A system of health accounts, OECD Publishing

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development health statistics database, (retrieved 23 March 2018)

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2017), Health at a Glance 2017

Office for National Statistics (2015), Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK: 2013

Office for National Statistics (2016), Introduction to health accounts

Office for National Statistics (2016), UK health accounts methodology

Office for National Statistics (2018), Public service productivity estimates, healthcare: 2015

United Nations (2008), A System of National Accounts, United Nations, New York

15. Quality and Methodology

The UK Health Accounts Quality and Methodology Information report contains important information on:

the strengths and limitations of the data and how it compares with related data

uses and users of the data

how the output was created

the quality of the output, including the accuracy of the data

More detailed information on methods is available in the Introduction to health accounts, and UK health accounts: methodological guidance

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys