Cynnwys

- Main points

- Latest figures

- Statistician’s comment

- Things you need to know about this release

- Overview of crime

- No change in most commonly occurring types of violent crime

- Offences involving weapons recorded by the police continue to rise

- Computer misuse offences show year-on-year fall

- No change in the volume of fraud offences in the last year

- Some types of offences involving theft are increasing

- What’s happened to the volume of crime recorded by the police?

- Other sources of data provide a fuller picture of crime

- New and upcoming changes to this bulletin

- Quality and methodology

1. Main points

While crime has fallen over the long-term, the short-term picture is more stable with most types of crime staying at similar levels to 2016. It is too early to say whether this indicates a change to the overall trend or simply a pause, which has happened before. The exceptions to this stable picture are rises in some types of theft and in lower-volume but higher-harm types of violence, and a fall in the high-volume offence of computer misuse.

As these figures cover a broad range of crime types and there is variation in the trends by crime type, it is better to consider the different types individually to understand these changes.

A fall in crime estimated by the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) was mainly driven by a 28% decrease in computer misuse offences, largely due to a decline in computer viruses.

For offences that are well recorded by the police, police recorded crime data provide insight into areas that the survey does not cover well. These include the less frequent but higher-harm violent offences, which showed rises:

- a 22% increase in offences involving knives or other sharp instruments

- an 11% increase in firearms offences

These offences tend to be disproportionately concentrated in London and other metropolitan areas.

There was also evidence of a rise in vehicle-related theft offences, with the latest CSEW estimates showing a 17% increase compared with the previous year. This is consistent with rises seen in the number of vehicle-related theft offences recorded by the police.

Police figures also indicate a rise in burglary (9% increase), which is thought to reflect a genuine increase in this type of crime.

To put these figures into context, most people do not experience crime. In the year ending December 2017, 8 in 10 adults were not a victim of any of the crimes asked about in the CSEW.

Many of the findings reported in this bulletin are consistent with those reported in the year ending September 2017 bulletin, released in January 2018.

Important points for interpreting figures in this bulletin

- An increase in the number of crimes recorded by the police does not necessarily mean the level of crime has increased.

- For many types of crime, police recorded crime statistics do not provide a reliable measure of levels or trends in crime.

- They only cover crimes that come to the attention of the police and can be affected by changes in policing activity and recording practice and by willingness of victims to report.

- The CSEW does not cover crimes against businesses or those not resident in households and is not well-suited to measuring trends in some of the more harmful crimes that occur in relatively low volumes.

- For offences that are well recorded by the police, police figures provide a useful supplement to the survey and provide insight into areas that the survey does not cover well.

2. Latest figures

A summary of what the latest figures show for different crime types, using the most appropriate data source for each, is given in Table 1. More detailed analysis by crime type is provided in sections 6 to 12 of this bulletin.

Table 1: What do the latest figures show?

| Figures for year ending December 2017 | Things to note | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Burglary | 9% increase in police recorded offences (to 438,971) | Burglary offences are thought to be relatively well reported by the public and relatively well recorded by the police and so the increase in police recorded burglary is likely to reflect a genuine increase. There was no change in burglary measured by the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW), but if the increase continues, we would expect this to show up in the survey in due course. | |

| Computer misuse | 28% decrease in offences estimated by the CSEW (to 1,374,000) | Falls in computer misuse crimes were the main driver of the overall decrease in crime estimated by the CSEW. Reports to Action Fraud show an increase in computer misuse offences, but these data cannot be compared with the CSEW estimates as they reflect only a small fraction of all computer misuse and include offences against businesses. | |

| Fraud | No change in offences estimated by the CSEW (3,241,000) | The CSEW provides the best indication of the overall trend in fraud as it captures the lower-harm cases that are more frequent but less likely to have been reported to the authorities. | |

| Homicide | 9% increase in police recorded offences (to 653 – excluding terrorist attacks in London and Manchester and events at Hillsborough in 1989) | The recent trend is affected by exceptional events with multiple homicide victims. While deaths resulting from the terrorist attacks and events at Hillsborough are included in the latest homicide figures, the figures presented in this table exclude these victims to provide a comparison on a more consistent basis. When the victims of these events are included in the figures, there was a 1% decrease in homicides recorded by the police (to 688). | |

| Robbery | 33% increase in police recorded offences (to 74,130) | Recording improvements are likely to have contributed to this rise, but the impact is thought to be less pronounced than for other crime types. Therefore, the increase may also reflect an element of a real change in these crimes. The CSEW does not provide a robust measure of short-term trends in robbery as it is a relatively low-volume crime. | |

| Vehicle-related theft | 17% increase in offences estimated by the CSEW (to 929,000) | A 16% increase was also seen in vehicle offences recorded by the police (to 452,683), continuing the rising trend seen over the last two years. Vehicle offences are thought to be relatively well reported by the public and well recorded by the police. | |

| Violence | No change in overall violent offences estimated by the CSEW (1,245,000) | The CSEW provides the better measure of trends in overall violent crime, covering the more common but less harmful offences. Police recorded crime provides a better measure of the more harmful but less common violent offences that are not well measured by the survey because of their relatively low volume. These offences are thought to be relatively well recorded by the police. | |

| 22% increase in police recorded knife or sharp instrument offences (to 39,598 offences) | |||

| 11% increase in police recorded firearms offences (to 6,604 offences) | |||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||

Download this table Table 1: What do the latest figures show?

.xls (41.5 kB)3. Statistician’s comment

"Today’s figures show that, for most types of offence, the picture of crime has been fairly stable, with levels much lower than the peak seen in the mid-1990s. Eight in ten adults had not experienced any of the crimes asked about in our survey in the latest year.

“However, we have seen an increase in the relatively rare, but "high-harm" violent offences such as homicide, knife crime and gun crime, a trend that has been emerging over the previous two years. We have also seen evidence that increases in some types of theft have continued, in particular vehicle-related theft and burglary.”

Alexa Bradley, Crime Statistics and Analysis, Office for National Statistics

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Things you need to know about this release

Sources included

This bulletin primarily reports on data from two main sources of crime data: the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) and police recorded crime. More information on both these sources can be found in the User guide to crime statistics for England and Wales.

Crime Survey for England and Wales

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is a face-to-face victimisation survey in which people resident in households in England and Wales are asked about their experiences of a selected range of offences in the 12 months prior to the interview. More information on the methodology can be found in the Crime in England and Wales Quality and Methodology Information report.

The CSEW does not cover all crimes. It does not cover crimes against businesses or those not resident in households (for example, people living in institutions or short-term visitors). The CSEW is also not well-suited to measuring trends in some of the more harmful crimes that occur in relatively low volumes. For example, there were around four cases of robbery per 1,000 people estimated by the CSEW in the last year. As the CSEW sample size is relatively small in terms of very low volume crimes, estimates of less frequently-occurring crime types can be subject to substantial variability making it difficult to detect short-term trends.

All changes reported in this bulletin, based on the CSEW, are statistically significant at the 5% level unless stated otherwise.

Police recorded crime

The other main source used in this bulletin is the number of crimes reported to and recorded by the police. These figures are principally a measure of the level of police activity related to crime and are useful in assessing how caseload has changed both in volume and nature over time.

Due to concerns over the quality and consistency of crime recording practice, police recorded crime data were assessed against the Code of Practice for Official Statistics (now the Code of Practice for Statistics) and found not to meet the required standard for designation as National Statistics1.

The National Statistics status of statistics about unlawful deaths based on the Homicide Index2 was restored in December 2016.

Information on why these two main data sources can sometimes show differing trends is published in the methodological note Why do the two data sources show differing trends? and more information is available in the User Guide to Crime Statistics for England and Wales.

Time periods covered

The latest CSEW figures presented in this release are based on interviews conducted between January 2017 and December 2017, measuring peoples’ experiences of crime in the 12 months before the interview.

The latest recorded crime figures relate to crimes recorded by the police during the year ending December 2017 (between January 2017 and December 2017).

In this release:

- “latest year” (or “latest survey year”) refers to the (survey) year ending December 2017

- “previous year” (or “previous survey year”) refers to the (survey) year ending December 2016

- any other time period is referred to explicitly

Crime statistics and the wider criminal justice system

The crime statistics reported in this release relate to only a part of the wider set of official statistics available on crime and other areas of the criminal justice system such as the outcomes of police investigations; the judicial process including charges, prosecutions and convictions; through to the management of prisons and prisoners.

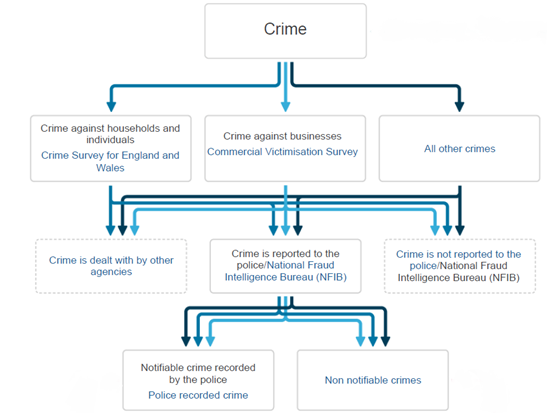

Some of these statistics are published by the Home Office or the Ministry of Justice. We have produced a flowchart showing the connections between the different aspects of crime and justice, as well as the statistics available for each area. The following diagram is an extract from that flowchart and highlights the portion of the process that is covered by statistics included in this release.

Crime and justice statistics flowchart

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Crime and justice statistics flowchart

.png (58.9 kB)Notes for: Things you need to know about this release

The full assessment report can be found on the UK Statistics Authority website. Data from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) continue to be badged as National Statistics.

Police forces supply a more detailed statistical return for each homicide (murders, manslaughters and infanticides) recorded in their force area to the Home Office than the main police recorded crime series. These returns are used to populate the Home Office database called the Homicide Index.

5. Overview of crime

Crime covers a wide range of offences, from the most harmful such as murder and rape through to relatively minor incidents of criminal damage or petty theft. Crime is often hidden and different types of offence occur in different circumstances and at different frequencies, meaning crime can never be measured entirely from any single source. The policy response to crime also tends to be specific to separate types of offence. Therefore, much of this bulletin focuses on individual types of crime.

CSEW estimated most types of crime have stayed at levels similar to the previous year

The latest estimates from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) show that most types of crime have stayed at levels similar to the previous year. However, the overall level of crime measured by the CSEW fell, driven mainly by decreases in computer misuse offences.

Crime estimated by the survey has fallen in the last year, but there is no significant change when fraud and computer misuse are excluded

England and Wales, year ending December 1981 to year ending December 2017

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data on this chart refer to different time periods: 1981 to 1999 refer to crimes experienced in the calendar year (January to December); and from year ending March 2002 onwards the estimates relate to crimes experienced in the 12 months before interview, based on interviews carried out in that financial year (April to March).

- Data relate to adults aged 16 and over or to households.

- New victimisation questions on fraud and computer misuse were incorporated into the CSEW from October 2015. The questions were asked of half the survey sample from October 2015 until September 2017, to test for detrimental effects on the survey as a whole and help ensure that the historical time series is protected, and have been asked of a full sample from October 2017.

- In March 2018 the new CSEW estimates on fraud and computer misuse were assessed by the Office for Statistics Regulation against the Code of Practice for Statistics and were awarded National Statistics status.

Download this chart Crime estimated by the survey has fallen in the last year, but there is no significant change when fraud and computer misuse are excluded

Image .csv .xlsThe CSEW is the most reliable indicator of the long-term trends in the more common types of crime experienced by the general population because it has used a consistent method over time and is unaffected by changes in reporting rates or police activity. It also measures more crime than is recorded by the police because it includes crimes that do not come to their attention.

Most people are not victims of crime

The latest CSEW estimate of 10.6 million crimes against the household population may seem like a big number, but most people do not experience crime. The survey showed that the large majority of adults (8 in 10) were not a victim of any of the crimes asked about in the survey in the previous 12 months.

Likelihood of being a victim has fallen considerably

Around 4 in 10 adults were estimated to have been a victim of crime in 1995; before the survey included fraud and computer misuse in its coverage. In the year ending December 2017, just over 1 in 10 adults were a victim of crimes comparable with those measured in the 1995 survey. Including fraud and computer misuse, 2 in 10 adults were a victim of crime in the year ending December 2017.

Overall fall in CSEW crime driven by decrease in computer misuse offences while vehicle-related thefts increased

The latest estimates from the CSEW show that most types of crimes have stayed at similar levels to the previous year. When looking at the main types of crime, changes were only seen in:

- computer misuse offences (28% decrease to 1.37 million offences), which drove the fall in overall CSEW crime

- vehicle-related thefts (17% increase to 929,000 offences), which is supported by a 16% increase in vehicle offences recorded by the police to 452,683 offences; a category that is well reported to the police and thought to be well recorded

All other main types of crime measured by the survey showed no change, although changes were seen in some of the sub-categories (see Appendix Table A1 for details). However, police recorded crime data showed evidence of rises in some other categories of crime, continuing the picture reported in the year ending September 2017 bulletin.

Recorded crime data only cover cases that are brought to the attention of the police and can be affected by varying policing priorities, activity and changes in crime-recording practices, and levels of public reporting. However, some types of crime are less affected by these issues and in these cases, the police figures can be a useful supplement to the CSEW and provide insight in areas which the survey does not cover well. The police figures indicate rises in the following types of crime:

- higher-harm violent offences involving the use of weapons

- offences of burglary and robbery

Genuine increases in some higher-harm violent offences

Violent crime covers a wide range of offences. The CSEW tends to provide the better measure of more common but less harmful crimes such as minor assault. The latest estimates from the survey show that violence was at a similar level to the previous year.

Police recorded crime is able to provide a measure that better covers the more harmful, less frequently-occurring offences that are not well measured by the survey. There is evidence of rises in some of these offences, which was most evident in the relatively low volume offences such as:

- offences involving knives or sharp instrument (up 22% to 39,598 recorded offences)

- offences involving firearms (up 11% to 6,604 recorded offences)

These offences tend to be disproportionately concentrated in London and other metropolitan areas; however, the majority of police force areas saw rises in these types of violent crime.

Knife or sharp instrument and firearm offences recorded by the police have shown an increase in the last two years

Embed code

Notes:

Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

Police recorded knife or sharp instrument offences data are submitted via an additional special collection. This special collection includes the offences: homicide; attempted murder; threats to kill; assault with injury and assault with intent to cause serious harm; robbery; rape; and sexual assault.

Firearms include: shotguns; handguns; rifles; imitation weapons such as BB guns or soft air weapons; other weapons such as CS gas, pepper spray and stun guns; and unidentified weapons. They exclude conventional air weapons, such as air rifles.

Although improved recording and more proactive policing may have contributed to these rises, there have also been genuine increases in these types of crime. This is supported by admissions data for NHS hospitals1 in England, which have shown an increase in admissions for assault by a sharp object and increases in all three categories of assault by firearm discharge.

Homicides (excluding Hillsborough and terror-related incidents) have increased

The total number of homicides recorded by the police fell by 1% (to 688). However, recent trends have been affected by the recording of exceptional incidents with multiple victims such as the terrorist attacks in London2 and Manchester, and events at Hillsborough in 19893. While deaths resulting from these events are included in the latest homicide figures, we have also analysed trends excluding these victims to provide a more consistent comparison.

If these cases are excluded, the latest figures show that there were 54 more homicides than the previous year, a 9% rise to 653. This continues an upward trend seen in homicides since March 2014, indicating a change to the long-term downward trend seen in the previous decade.

Excluding terror attacks in London and Manchester and crimes recorded as a result of events at Hillsborough, homicides have increased over the last three years

England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending December 2017

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

- Data on homicide offences given in these police recorded crime data will differ from data from the Home Office Homicide Index, which are published annually by ONS, last released as part of Homicide in England and Wales: year ending March 2017. Police recorded crime data on homicide represent the recording decision of the police based on the available information at the time the offence comes to their attention. Homicide Index data take account of the charging decision and court outcome in cases that have gone to trial. It is not uncommon for offences initially recorded as murder by the police to be charged or convicted as manslaughter at court.

Download this chart Excluding terror attacks in London and Manchester and crimes recorded as a result of events at Hillsborough, homicides have increased over the last three years

Image .csv .xlsAlthough police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics, the National Statistics status of statistics about unlawful deaths based on the Homicide Index4 was restored in December 2016.

Vehicle-related theft and burglary are also thought to show genuine increases

In addition to the increase in vehicle-related theft shown by both the CSEW and police recorded crime, there is also evidence of increases in burglary recorded by the police, which increased by 9% (up to 438,971 offences). This is thought to reflect a genuine increase in this type of crime because it is generally well recorded by the police and well reported by victims. If the increases in burglary recorded by the police continue, we would expect these to show up in the survey in due course.

The police have also recorded a rise in robbery (up 33% to 74,130 offences). Recording improvements are likely to have contributed to this rise, but the impact is thought to be less pronounced than for other crime types. Therefore, the increase may also reflect a real change in these crimes. The CSEW does not provide a robust measure of short-term trends in robbery as it is a relatively low-volume crime.

Rises in vehicle offences, burglary and robbery recorded by the police are thought to reflect genuine increases

England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending December 2017

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

Download this chart Rises in vehicle offences, burglary and robbery recorded by the police are thought to reflect genuine increases

Image .csv .xlsMore detailed analysis by crime type is provided in sections 6 to 12 of this bulletin and further breakdown is provided in the Appendix tables published alongside this bulletin.

CSEW and police recorded crime figures for main crime types

Table 2a: Crime Survey for England and Wales incidence rates and number of incidents for year ending December 2017 and percentage change

| England and Wales | Adults aged 16 and over/households | |||||

| January 2017 to December 2017 compared with: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offence group2 | Jan '17 to Dec '17 | Jan '95 to Dec '95 | Jan '16 to Dec '16 | |||

| Rate per 1,000 population3 | Number of incidents (thousands)4 | Number of incidents - percentage change and significance5 | ||||

| Violence | 27 | 1,245 | -68 | * | -7 | |

| Robbery | 4 | 175 | -48 | * | 39 | |

| Theft offences6 | : | 3,466 | -70 | * | 1 | |

| Theft from the person | 8 | 384 | -44 | * | 5 | |

| Other theft of personal property | 14 | 635 | -69 | * | -10 | |

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 34,529 | 34,529 | ||||

| Domestic burglary | 28 | 689 | -71 | * | 4 | |

| Other household theft | 22 | 554 | -65 | * | -9 | |

| Unweighted base - number of households | 34,453 | 34,453 | ||||

| Vehicle-related theft | 48 | 929 | -78 | * | 17 | * |

| Unweighted base - number of vehicle owners | 27,685 | 27,685 | ||||

| Bicycle theft | 23 | 274 | -58 | * | -8 | |

| Unweighted base - number of bicycle owners | 16,260 | 16,260 | ||||

| Criminal damage | 45 | 1,119 | -66 | * | -5 | |

| Unweighted base - number of households | 34,453 | 34,453 | ||||

| All CSEW CRIME EXCLUDING FRAUD AND COMPUTER MISUSE6 | : | 6,004 | -69 | * | -1 | |

| Fraud and computer misuse7 | 99 | 4,615 | .. | -15 | * | |

| Fraud | 70 | 3,241 | .. | -7 | ||

| Computer misuse | 30 | 1,374 | .. | -28 | * | |

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 20,974 | 20,974 | ||||

| All CSEW CRIME INCLUDING FRAUD AND COMPUTER MISUSE 6,8 | : | 10,619 | .. | -7 | * | |

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | ||||||

| Notes: | ||||||

| 1. More detail on further years can be found in Appendix tables A1 and A2. | ||||||

| 2. Section 5 of the User Guide provides more information about the crime types included in this table. | ||||||

| 3. Rates for violence, robbery, theft from the person and other theft of personal property are quoted per 1,000 adults; rates for domestic burglary, other household theft, and criminal damage are quoted per 1,000 households; rates for vehicle-related theft and bicycle theft are quoted per 1,000 vehicle-owning and bicycle-owning households respectively. | ||||||

| 4. Data may not sum to totals shown due to rounding. | ||||||

| 5. Statistically significant change at the 5% level is indicated by an asterisk. | ||||||

| 6. : denotes not available. It is not possible to construct a rate for all theft offences or CSEW crime because rates for household offences are based on rates per household, and those for personal offences on rates per adult, and the two cannot be combined. | ||||||

| 7. New victimisation questions on fraud and computer misuse were incorporated into the CSEW from October 2015. Up to the year ending September 2017 the questions were asked of half the survey sample. From October 2017 onwards the questions are being asked of a full survey sample. | ||||||

| 8. This combined estimate is not comparable with headline estimates from earlier years. For year-on-year comparisons and analysis of long-term trends it is necessary to exclude fraud and computer misuse offences, as data on these are only available for the latest year. | ||||||

| .. Denotes not available as data not collected. | ||||||

Download this table Table 2a: Crime Survey for England and Wales incidence rates and number of incidents for year ending December 2017 and percentage change

.xls (273.4 kB)

Table 2b: Crime Survey for England and Wales prevalence rates and numbers of victims for year ending December 2017 and percentage change1

| England and Wales | Adults aged 16 and over/households | ||||||

| January 2017 to Decembmber 2017 compared with: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offence group2 | Jan '17 to Dec '17 | Jan '95 to Dec '95 | Jan '16 to Dec '16 | ||||

| Percentage, victims once or more3 | Number of victims (thousands)4 | Numbers of victims - percentage change and significance5 | |||||

| Violence | 1.7 | 792 | -59 | * | -5 | ||

| Robbery | 0.3 | 133 | -52 | * | 18 | ||

| Theft offences6 | 9.9 | 4,602 | -64 | * | 3 | ||

| Theft from the person | 0.8 | 358 | -45 | * | 5 | ||

| Other theft of personal property | 1.2 | 572 | -66 | * | -8 | ||

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 34,529 | 34,529 | |||||

| Domestic burglary | 2.3 | 566 | -69 | * | 9 | ||

| Other household theft | 1.8 | 454 | -58 | * | -10 | ||

| Unweighted base - number of households | 34,453 | 34,453 | |||||

| Vehicle-related theft | 4.1 | 787 | -74 | * | 16 | * | |

| Unweighted base - number of vehicle owners | 27,685 | 27,685 | |||||

| Bicycle theft | 2.1 | 255 | -55 | * | -5 | ||

| Unweighted base - number of bicycle owners | 16,260 | 16,260 | |||||

| Criminal damage | 3.3 | 820 | -61 | * | -4 | ||

| Unweighted base - number of households | 34,453 | 34,453 | |||||

| All CSEW crime7 | 14.2 | 6,600 | -59 | * | 1 | ||

| Fraud and computer misuse8 | 8.0 | 3,708 | .. | -11 | * | ||

| Fraud | 5.9 | 2,730 | .. | -4 | |||

| Computer misuse | 2.4 | 1,125 | .. | -25 | * | ||

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 20,974 | 20,974 | |||||

| All CSEW CRIME INCLUDING FRAUD AND COMPUTER MISUSE 9 | 20.0 | 9,309 | .. | -5 | * | ||

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. More detail on further years can be found in Appendix tables A3 and A8. | |||||||

| 2. Section 5 of the User Guide provides more information about the crime types included in this table. | |||||||

| 3. Percentages for violence, robbery, theft from the person and other theft of personal property are quoted for adults; percentages for domestic burglary, other household theft, and criminal damage are quoted for households; percentages for vehicle-related theft and bicycle theft are quoted for vehicle-owning and bicycle-owning households respectively. | |||||||

| 4. Where applicable, numbers in sub-categories will not sum to totals, because adults/households may have been a victim of more than one crime. | |||||||

| 5. Statistically significant change at the 5% level is indicated by an asterisk. | |||||||

| 6. This is the estimated percentage/number of adults who have been a victim of at least one personal theft crime or have been resident in a household that was a victim of at least one household theft crime. | |||||||

| 7. This is the estimated percentage/number of adults who have been a victim of at least one personal crime or have been resident in a household that was a victim of at least one household crime. | |||||||

| 8. New victimisation questions on fraud and computer misuse were incorporated into the CSEW from October 2015. Up to the year ending September 2017 the questions were asked of half the survey sample. From October 2017 onwards the questions are being asked of a full survey sample. | |||||||

| 9. This combined estimate is not comparable with headline estimates from earlier years. For year-on-year comparisons and analysis of long-term trends it is necessary to exclude fraud and computer misuse offences, as data on these are only available for the latest year. | |||||||

| .. Denotes not available. | |||||||

Download this table Table 2b: Crime Survey for England and Wales prevalence rates and numbers of victims for year ending December 2017 and percentage change^1^

.xls (274.4 kB)Caution should be taken when interpreting police recorded crime trends

A renewed focus on the quality of crime recording by the police in recent years is thought to have led to improved compliance with the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS), leading to a greater proportion of reported crimes being recorded by the police5. Despite improvements made in recording in recent years, the latest inspection reports6 from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) suggest that some offences, such as violent crime, are still significantly under-recorded by the police7. For more information see the Quality and methodology section in Crime in England and Wales: year ending March 2017.

Given the different factors affecting the reporting and recording of offences by the police, these data do not currently provide a reliable indication of current trends in crime and must be interpreted with caution. Although police recorded crime data cannot provide a reliable estimate of trends in the prevalence of crime, they do provide information about demands on the police in relation to these offences.

For more information about crimes recorded by the police, see What’s happened to the volume of crime recorded by the police?

Table 3: Police recorded crimes in England and Wales – rate, number and percentage change for year ending December 2017

| England and Wales | |||||||

| January 2017 to December 2017 compared with: | |||||||

| Offence group | Jan '17 to Dec '17 | Apr '06 to Mar '07 | Jan '16 to Dec '16 | ||||

| Rate per 1,000 population | Number of offences | Number of offences - percentage change | |||||

| VICTIM-BASED CRIME | 72 | 4,174,919 | -13 | 14 | |||

| Violence against the person offences | 23 | 1,349,154 | 66 | 21 | |||

| Homicide | < 0.1 | 688 | -9 | -1 | |||

| Death or serious injury - unlawful driving4 | < 0.1 | 718 | 51 | -2 | |||

| Violence with injury5 | 9 | 505,244 | -0 | 11 | |||

| Violence without injury6 | 10 | 563,313 | 126 | 25 | |||

| Stalking and harrassment7 | 5 | 279,191 | 380 | 33 | |||

| Sexual offences | 2 | 145,397 | 159 | 25 | |||

| Rape | 1 | 51,833 | 276 | 31 | |||

| Other sexual offences | 2 | 93,564 | 121 | 22 | |||

| Robbery offences | 1 | 74,130 | -27 | 33 | |||

| Theft offences | 34 | 2,011,942 | -24 | 11 | |||

| Burglary | 8 | 438,971 | -29 | 9 | |||

| Vehicle offences | 8 | 452,683 | -41 | 16 | |||

| Theft from the person | 2 | 99,101 | -14 | 15 | |||

| Bicycle theft | 2 | 102,581 | -7 | 13 | |||

| Shoplifting | 7 | 385,265 | 31 | 8 | |||

| All other theft offences8 | 9 | 533,341 | -27 | 9 | |||

| Criminal damage and arson | 10 | 594,296 | -50 | 7 | |||

| OTHER CRIMES AGAINST SOCIETY | 11 | 630,447 | 18 | 26 | |||

| Drug offences | 2 | 134,461 | -31 | -4 | |||

| Possession of weapons offences | 1 | 36,666 | -6 | 25 | |||

| Public order offences | 6 | 368,551 | 56 | 42 | |||

| Miscellaneous crimes against society | 2 | 90,769 | 41 | 28 | |||

| TOTAL RECORDED CRIME - ALL OFFENCES EXCLUDING FRAUD | 82 | 4,805,366 | 41 | 15 | |||

| TOTAL FRAUD OFFENCES9 | 11 | 639,457 | .. | -0 | |||

| TOTAL RECORDED CRIME - ALL OFFENCES INCLUDING FRAUD9 | 93 | 5,444,823 | .. | 13 | |||

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | |||||||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics. | |||||||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police). | |||||||

| 3. Appendix tables A4 and A7 provide detailed footnotes and further years. | |||||||

| 4. Includes causing death or serious injury by dangerous driving, causing death by careless driving when under the influence of drink or drugs, causing death by careless or inconsiderate driving, causing death by driving: unlicensed or disqualified or uninsured drivers, causing death by aggravated vehicle taking. | |||||||

| 5.Includes attempted murder, intentional destruction of viable unborn child, more serious wounding or other act endangering life (including grievous bodily harm with and without intent) and less serious wounding offences. | |||||||

| 6. Includes threat or conspiracy to murder, other offences against children and assault without injury (formerly common assault where there is no injury). | |||||||

| 7. Includes harassment, racially or religously motivated harassment, stalking, malicous communications. | |||||||

| 8. All other theft offences now includes all 'making off without payment' offences recorded since year ending March 2003. Making off without payment was previously included within the fraud offence group, but following a change in the classification for year ending March 2014, this change has been applied to previous years of data to give a consistent time series. | |||||||

| 9. Total fraud offences cover crimes recorded by the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau via Action Fraud, Cifas and Financial Fraud Action UK. Action Fraud have taken over the recording of fraud offences on behalf of individual police forces. Percentage changes compared with year ending March 2007 are not presented, as fraud figures covered only those crimes recorded by individual police forces. Given the addition of new data sources, it is not possible to make direct comparsions with years prior to Year ending March 2012. | |||||||

Download this table Table 3: Police recorded crimes in England and Wales – rate, number and percentage change for year ending December 2017

.xls (44.5 kB)Notes for: Overview of crime

Data are from NHS Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2015 to 2016 and NHS Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2016 to 2017. See the "External Causes" dataset.

Includes victims of the London Bridge and Borough Market, and Westminster attacks. Events at Finsbury Park are not included as there were not multiple victims of homicide.

96 offences of manslaughter from Hillsborough were recorded in April 2016 when the inquest into these events concluded.

Police forces supply a more detailed statistical return for each homicide (murders, manslaughters and infanticides) recorded in their force area to the Home Office than the main police recorded crime series. These returns are used to populate the Home Office database called the Homicide Index.

The Crime-recording: making the victim count report, published by HMICFRS in late 2014, found that violent offences had been substantially under-recorded (by 33% nationally) and led to police forces reviewing and improving their recording processes.

These reports were published during 2016 and 2018, and the most recent reports were published on 15 February 2018. Three re-inspection reports were published on 10 April 2018.

Of the 20 published inspection reports, only five forces received a rating of “good”, with a further five rated as “requires improvement” and 10 as “inadequate”. Three forces rated as “inadequate” have since been re-inspected and their ratings improved, with two of these forces rated as “good” and one as “requires improvement”.

6. No change in most commonly occurring types of violent crime

Violent crime covers a wide range of offences including minor assaults (such as pushing and shoving), harassment and psychological abuse (that result in no physical harm), through to wounding, physical assault and death. Neither of our two main sources provide a full picture of violent crime. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) data include incidents with and without injury. Violent offences in police recorded data are referred to as “violence against the person” and include homicide, death or serious injury caused by unlawful driving, violence with injury, violence without injury, and stalking and harassment1. Attempted offences are included in both “violence with injury” and “violence without injury” figures.

CSEW is the best measure of trends in most common types of violence

The CSEW provides the better measure of trends for the population and violent offences that it covers. It has used a consistent methodology since the survey began in 1981 and covers crimes that are not reported to or recorded by the police. In the year ending March 2017, the CSEW showed that more than half of violent crime victims (57%) did not report their experiences to the police, a return to levels seen preceding the year ending March 2013, following higher levels of reporting in the previous three years. In addition, police recorded crime statistics may be affected by changes in recording practices and police activity.

One very important difference between the two measures of crime relates to how each are able to measure some forms of crime better than others; the CSEW tends to provide the better measure of more common but less harmful crimes while police recorded crime is able to provide a measure that better covers the more harmful, less frequently-occurring offences that come to their attention such as homicide, knife crime and gun crime.

CSEW has shown no change in level of violence in recent years

There were an estimated 1.2 million incidents of violence experienced by adults aged 16 and over in the latest CSEW survey year ending December 2017; no significant change from the previous year. Both “violence with injury” and “violence without injury” showed no significant change.

Crime Survey for England and Wales shows long-term reductions in violent crime but little change in recent years

England and Wales, year ending December 1981 to year ending December 2017

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Prior to the year ending March 2002, CSEW respondents were asked about their experience of crime in the previous calendar year, so year-labels identify the year in which the crime took place. Following the change to continuous interviewing, respondents’ experience of crime relates to the full 12 months prior to interview (that is, a moving reference period). Year-labels for the year ending March 2002 identify the CSEW year of interview.

Download this chart Crime Survey for England and Wales shows long-term reductions in violent crime but little change in recent years

Image .csv .xlsAround 2 in every 100 adults were a victim of CSEW violent crime in the latest survey year, compared with around 3 in 100 adults in the survey year ending March 2007 and 5 in 100 adults in 1995 (the peak year).

Long-term reductions in violent crime supported by other data

The longer-term reductions in violent crime, as shown by the CSEW, are also reflected in the findings of the most recent admissions data for NHS hospitals in England. Assault admissions for the year ending March 20172 (26,450) are 42% lower than the year ending March 2007 (45,890 admissions). In addition, research conducted by the Violence and Society Research Group at Cardiff University (PDF, 502KB) shows similar findings. Results from their annual survey, covering a sample of hospital emergency departments and walk-in centres in England and Wales, show that serious violence-related attendances in 2017 have fallen 39% since 2010. However, similar to the latest CSEW findings, the latest data show little change in 2017 compared with 2016 (1% increase).

Estimates of violence against 10-to-15-year-olds, as measured by the CSEW, can be found in Appendix tables A9, A10, A11 and A12. The estimates are not directly comparable with the main survey of adults, so are not included in the headline totals.

Police recorded crime can be a good measure of less common types of violence

While the CSEW gives us a good picture of the overall trend in violent crime, it is not good at measuring some types of violence. In these cases, police recorded crime is a useful source as the better measure of the higher-harm but less common types of violence. The police recorded continuing rises in a number of such offences that are either not covered or not well-measured by the survey due to their low volume – homicide, firearm offences and knife or sharp instrument offences. See Offences involving weapons recorded by the police continue to rise for further information on offences involving weapons.

Homicide (excluding Hillsborough and terror-related incidents) has increased

Unlike many other violence against the person offences, the quality of recording of homicides by the police is thought to have remained consistently good.

The police recorded 688 homicides3,4, in the latest year to December 2017, a 1% fall compared with the previous year (Table A4). However, recent trends in homicide have been affected by the recording of incidents with multiple victims. Of the 688 homicides recorded in the year ending December 2017, 35 related to the London and Manchester terror attacks. The 96 cases of manslaughter that occurred at Hillsborough in 1989 were recorded in the previous year.

Excluding the Hillsborough cases from the year ending December 2016 and the London and Manchester terror attacks from the year ending December 2017, there was a volume rise of 54 homicides (a 9% rise, up to a total of 653). This follows the general upward trend seen in the last three years and contrasts with the previously downward trend since the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in 2002.

Homicides have increased over the last three years, excluding crimes recorded as a result of Hillsborough and London and Manchester terror attacks

England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending December 2017

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

- Data on homicide offences given in these police recorded crime data will differ from data from the Home Office Homicide Index, which are published annually by ONS, last released as part of Homicide in England and Wales: year ending March 2017. Police recorded crime data on homicide represent the recording decision of the police based on the available information at the time the offence comes to their attention. Homicide Index data take account of the charging decision and court outcome in cases that have gone to trial. It is not uncommon for offences initially recorded as murder by the police to be charged or convicted as manslaughter at court.

- The homicide figure for year ending March 2003 includes 172 homicides attributed to Harold Shipman.

- The homicide figure in year ending March 2006 includes 52 victims of the 7 July London bombings.

- The homicide figure for year ending March 2017 includes 96 victims of Hillsborough.

- The year ending December 2017 includes 35 victims of the Manchester Arena bombing, and London terror attacks.

Download this chart Homicides have increased over the last three years, excluding crimes recorded as a result of Hillsborough and London and Manchester terror attacks

Image .csv .xlsThe number of homicides where a knife or sharp instrument had been used has increased by 26% in the last year (from 209 to 264 offences). For more information on crimes involving a knife or sharp instrument, see Table 4.

Homicide rate has fallen in last decade

Historically, the number of homicides increased from around 300 per year in the early 1960s to over 800 per year in the early years of this century, which was at a faster rate than population growth over the same period. However, over the past decade, the volume of homicides has generally decreased while the population of England and Wales has continued to grow. The rate of homicide fell 17% between the year ending March 2007 and the year ending December 2017, from 14 homicides per 1 million of the population to 12 homicides per 1 million, although small increases have been seen in the last two years.

Small decrease in death or serious injury caused by unlawful driving

A sub-category covering offences related to death or serious injury caused by unlawful driving has been included within the violence against the person offence group since the year ending June 2017. It contains offences previously counted under “violence with injury”. This sub-category saw a 2% decrease compared with the previous year (718 down from 732 offences). This is in contrast with recent years where there has been a rising trend. As with homicide offences, this category is thought to be well-recorded by the police.

Other types of violence recorded by the police are not thought to provide a reliable measure of trends in violent crime. Factors influencing changes in police recorded violence are described in more detail in What’s happened to the volume of crime handled by the police?

There is more detailed information on long-term trends and the circumstances of violence in The nature of violent crime in England and Wales: year ending March 2017 and Homicide in England and Wales: year ending March 2017. However, these articles do not include the most recent statistics for the year ending December 2017.

Notes for: No change in most commonly occurring types of violent crime

There are some closely-related offences in the police recorded crime series, such as public order offences, that have no identifiable victim and are contained within the “other crimes against society” category.

Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2016-17 and Hospital Episode Statistics, Admitted Patient Care – England, 2006-07 provided by NHS Digital. Assault admissions do not include sexual offences but include assault codes X85-Y04 and Y08 and Y09 from the dataset.

Homicide includes the offences of murder, manslaughter, corporate manslaughter and infanticide. Figures from the Homicide Index for the time period April 2016 to March 2017, which take account of further police investigations and court outcomes, were published in Homicide in England and Wales: year ending March 2017 on 8 February 2018.

These figures include murders related to the Westminster Bridge terrorist-related incident in March 2017. It also includes seven offences of corporate manslaughter relating to the Croydon tram crash.

7. Offences involving weapons recorded by the police continue to rise

Some of the more serious offences in the police recorded crime data can be broken down by whether or not a knife or sharp instrument was involved1. The overall number of offences involving a knife or sharp instrument has seen an increase in the last year, with increases in all offences included within the data collection.

Data are also available for police recorded crimes involving the use of firearms (that is, if a firearm is fired, used as a blunt instrument, or used as a threat). Offences involving the use of a firearm have also seen an increase in the last year.

While these offences are relatively well recorded by the police, they can only provide a partial picture as not all offences will come to their attention.

As offences involving the use of weapons are relatively low in volume, the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is not able to provide reliable trends for such incidents.

Highest number of offences involving knives or sharp instruments since 20112

Police recorded knife or sharp instrument offences data are submitted via an additional special collection. Proportions of offences involving the use of a knife or sharp instrument presented in this section are calculated based on figures submitted in this special collection. Other offences exist that are not shown in this section that may include the use of a knife or sharp instrument.

The police recorded 39,598 offences involving a knife or sharp instrument in the latest year ending December 2017, a 22% increase compared with the previous year (32,468) and the highest number in the seven-year series (from year ending March 2011), the earliest point for which comparable data are available3. The past three years have seen a rise in the number of recorded offences involving a knife or sharp instrument, following a general downward trend in this series since the year ending March 2011.

Increases evident in police recorded offences involving a knife or sharp instrument for the third year

England and Wales, year ending March 2011 to year ending December 2017

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

Download this chart Increases evident in police recorded offences involving a knife or sharp instrument for the third year

Image .csv .xlsThe offences “assault with injury” and “assault with intent to cause serious harm” accounted for around half (49%) of total selected offences involving a knife or sharp instrument (Table 4). All offence categories for which data are collected showed increases.

Table 4: Selected violent and sexual offences involving a knife or sharp instrument recorded by the police

| England and Wales, year ending December 2016 and year ending December 2017 with percentage change | |||

| England and Wales | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan '16 to Dec '16 | Jan '17 to Dec '17 | Jan '17 to Dec '17 compared with previous year | |

| Selected offences involving a knife or sharp instrument | Number of offences | Percentage change | |

| Attempted murder | 322 | 385 | 20 |

| Threats to kill | 2,591 | 2,868 | 11 |

| Assault with injury and assault with intent to cause serious harm | 16,778 | 19,213 | 15 |

| Robbery | 12,039 | 16,229 | 35 |

| Rape | 375 | 448 | 19 |

| Sexual assault6 | 154 | 191 | 24 |

| Total selected offences | 32,259 | 39,334 | 22 |

| Homicide7 | 209 | 264 | 26 |

| Total selected offences including homicide | 32,468 | 39,598 | 22 |

| Rate per million population - selected offences involving a knife or sharp instrument | |||

| Total selected offences including homicide | 561 | 675 | |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | |||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics. | |||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police). | |||

| 3. Police recorded knife and sharp instrument offences data are submitted via an additional special collection. Proportions of offences involving the use of a knife or sharp instrument presented in this table are calculated based on figures submitted in this special collection. Other offences exist that are not shown in this table that may include the use of a knife or sharp instrument. | |||

| 4. Data from Surrey Police include unbroken bottle and glass offences, which are outside the scope of this special collection; however, it is not thought that offences of this kind constitute a large enough number to impact on the national figure. | |||

| 5. Numbers differ from those previously published due to Sussex Police revising their figures to exclude unbroken bottles. | |||

| 6. Sexual assault includes indecent assault on a male/female and sexual assault on a male/female (all ages). | |||

| 7. Homicide offences are those currently recorded by the police as at 21st February 2018 and are subject to revision as cases are dealt with by the police and by the courts, or as further information becomes available. They include the offences of murder, manslaughter, infanticide and, as of year ending March 2013, corporate manslaughter. These figures are taken from the detailed record level Homicide Index (rather than the main police collection for which forces are only required to provide an overall count of homicides, used in Appendix table A4). There may therefore be differences in the total homicides figure used to calculate these proportions and the homicide figure presented in Appendix table A4. | |||

Download this table Table 4: Selected violent and sexual offences involving a knife or sharp instrument recorded by the police

.xls (42.0 kB)The majority of police forces (37 of the 44)4 recorded a rise in offences involving knives or sharp instruments. The Metropolitan Police had the largest volume increase (accounting for 48% of the total increase). A breakdown of offences for each police force and the time series for these data are published in the Home Office’s knife crime open data table5.

Recent increases reflect a real rise in offences involving knives or sharp instruments

While it is thought that improvements in recording practices have contributed to the recent increases in recorded knife or sharp instrument offences, these increases also reflect a real rise in the occurrence of these types of crime, representing a change to the downward trend seen in recent years.

This is supported by evidence from admissions data for NHS hospitals in England6, which showed a 7% increase in admissions for assault by a sharp object, from 4,054 in the year ending March 2016 to 4,351 in the year ending March 2017.

Possession of an article with a blade or point also rose

Police recorded “possession of an article with a blade or point” offences also rose, by 33%, to 17,437 offences in the latest year. This rise is consistent with increases seen over the last four years, but this is the highest figure since the series began in the year ending March 2009. This figure can often be influenced by increases in targeted police action in relation to knife crime, which is most likely to occur at times when rises in offences involving knives are seen.

Offences involving firearms have increased following long-term declines

Offences involving firearms7 increased by 11% (to 6,604) in the year ending December 2017 compared with the previous year (5,945 offences).

Police recorded firearms offences have increased over the last three years

England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending December 2017

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

- Firearms include: shotguns; handguns; rifles; imitation weapons such as BB guns or soft air weapons; other weapons such as CS gas, pepper spray and stun guns; and unidentified weapons. They exclude conventional air weapons, such as air rifles.

Download this chart Police recorded firearms offences have increased over the last three years

Image .csv .xlsThis was driven by:

- a 12% increase in offences involving handguns (up to 2,808 from 2,507, accounting for 46% of the overall increase)

- a 21% increase in offences involving unidentified firearms (up to 908 from 753)

- a 20% increase in offences involving shotguns (up to 655 from 548)

The latest rise continues an upward trend seen in firearms offences in the last few years, however, offences are still 32% below a decade ago (in the year ending March 2007).

Some of the increase in offences involving firearms is genuine

Some of the increase in the number of offences involving firearms is a genuine rise. Evidence of a genuine rise can be seen in admissions data for NHS hospitals in England , which showed increases in all three categories of assault by firearm discharge9, from 109 admissions in the year ending March 2016 to 135 admissions in the year ending March 2017.

But it is likely that improvements in crime recording have also been a factor. For example:

- around one-third (32%)10 of the rise is due to an increase in possession of firearms offences with intent – these offences may have been recorded as simple possession offences previously, which are not covered by this data collection

- around one-tenth (9%)11 of the increase is in offences involving some of the less serious weapons such as BB guns and CS gas12 – it is likely that these are now included in police returns when previously they were excluded

While a full geographic breakdown is not yet available, information from police forces suggests that the majority of areas have seen increases in recorded offences involving firearms, with 63% of the increase in England and Wales occurring in the Metropolitan Police force area (36%) and the Greater Manchester Police force area (27%).

Recently published data by London’s Air Ambulance Data are from London’s Air Ambulance Mission Maps 2017. These data also suggest an increase in serious offences involving a weapon. In 2017, injuries resulting from stabbings and shootings were the most common cause for a helicopter to be dispatched, overtaking trauma resulting from road traffic collisions.

Further analysis on offences involving knives or sharp instruments and firearms, including figures based on a broader definition of the types of firearm involved14, can be found in Offences involving the use of weapons: data tables. However, this does not include the most recent statistics for the year ending December 2017.

Notes for: Offences involving weapons recorded by the police continue to rise

These are: homicide; attempted murder; threats to kill; assault with injury and assault with intent to cause serious harm; robbery; rape; and sexual assault.

A sharp instrument is any object that pierces the skin (or in the case of a threat, is capable of piercing the skin), for example, a broken bottle.

The Focus on violent crime and sexual offences publication includes data on offences involving a knife or sharp instrument going back to the year ending March 2009; however, this excludes data for West Midlands and Sussex due to inconsistencies in their recording practices, which did not change until the year ending March 2011. Data for the year ending March 2017 are published in the Offences involving the use of weapons: data tables.

At time of publication, Greater Manchester Police were reviewing their knife crime figures, therefore data should be used with caution. Data will be updated following the review.

See Homicide in England and Wales: Appendix tables for more information on homicides committed using a knife or sharp instrument.

Data are from NHS Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2015 to 2016 and NHS Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2016 to 2017. See the “External Causes” dataset.

Firearms include: shotguns; handguns; rifles; imitation weapons such as BB guns or soft air weapons; other weapons such as CS gas or pepper spray and stun guns; and unidentified weapons. These figures exclude conventional air weapons, such as air rifles.

Data are from NHS Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2015 to 2016 and NHS Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2016 to 2017.

Firearm discharge admissions categories are: “assault by handgun discharge”, “assault by rifle, shotgun and larger firearm discharge” and “assault by other and unspecified firearm discharge.”

Data not shown.

Data not shown.

BB guns, soft air weapons, CS Gas and pepper spray.

Data are from London’s Air Ambulance Mission Maps 2017.

The broader definition of firearms includes conventional air weapons, such as air rifles.

8. Computer misuse offences show year-on-year fall

New questions on computer misuse were introduced to half of the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) sample from October 2015, and increased to a full sample from October 2017.

We can look at changes in these estimates over the last two years. However, as this comparison is based on two data points only, caution must be taken in drawing conclusions about trends at this early stage.

Fall in CSEW computer viruses drives fall in computer misuse

Offences involving computer misuse showed a 28% decrease from the survey year ending December 2016 (down to 1.4 million offences from 1.9 million), largely owing to a 34% fall in “computer viruses” (down to 840,000 offences).

Table 5: Crime Survey for England and Wales computer misuse - number of incidents for year ending December 2016 and year ending December 2017 with percentage change1 2

| England and Wales | Adults aged 16 and over | |||

| Offence group | Jan '16 to Dec '16 | Jan '17 to Dec '17 | Percentage change and significance3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of incidents (thousands) | ||||

| Computer misuse | 1,917 | 1,374 | -28 | * |

| Computer virus | 1,275 | 840 | -34 | * |

| Unauthorised access to personal information (including hacking) | 642 | 534 | -17 | |

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 17,500 | 20,974 | ||

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | ||||

| 1. New victimisation questions on computer misuse were incorporated into the CSEW from October 2015. Up to the year ending September 2017 the questions were asked of half the survey sample. From October 2017 onwards the questions are being asked of a full survey sample. | ||||

| 2. In March 2018 the new CSEW estimates on computer misuse were assessed by the Office for Statistics Regulation against the Code of Practice for Statistics and were awarded National Statistics status. | ||||

| 3. Statistically significant change at the 5% level is indicated by an asterisk. | ||||

Download this table Table 5: Crime Survey for England and Wales computer misuse - number of incidents for year ending December 2016 and year ending December 2017 with percentage change^1^ ^2^

.xls (38.9 kB)What do incidents of computer misuse reported to Action Fraud show?

“Computer misuse crime”1 referred to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB) by Action Fraud increased by 36% (up to 22,154 offences), largely accounted for by a rise in “hacking – social media and email” over the last year (up 74% to 7,792 offences).

In interpreting these figures it is important to consider that incidents of computer misuse reported to Action Fraud represent only a small fraction of all computer misuse, as many incidents are not reported. As such, it is not possible to make meaningful comparisons with computer misuse measured by the CSEW. The latest rise in Action Fraud reports is likely to reflect an increasing awareness of social media scams among the public, leading to a greater likelihood of such offences being reported.

A large rise was also seen in computer viruses reported to Action Fraud over the last year (up 53% to 7,954 offences), which is thought to be due to a rise in levels of malware (mainly ransomware and Trojans), including several high-profile attacks and security breaches on national institutions (for example, the WannaCry virus linked to the NHS cyberattack in May 2017). Such offences would not have been captured by the CSEW as the primary victims were organisations rather than individuals.

Notes for Computer misuse offences show year-on-year fall:

- Computer misuse crime covers any unauthorised access to computer material, as set out in the Computer Misuse Act 1990.

9. No change in the volume of fraud offences in the last year

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) provides the best indication of the volume of fraud offences directly experienced by individuals in England and Wales. CSEW estimates cover a wide range of fraud offences, including attempts and offences involving a loss, and include incidents not reported to the authorities. Latest findings from the survey estimated the number of fraud incidents to be similar to the previous survey year.

A similar picture of no change was also shown by the overall number of recorded crime incidents referred to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB) by Action Fraud – the public-facing national fraud and cybercrime reporting centre, as well as two industry bodies, Cifas and UK Finance1,2, who report instances of fraud where their member organisations have been a victim.

The number of incidents estimated by the CSEW is substantially higher than the number of incidents referred to the NFIB, as the survey captures a large volume of lower-harm cases that are less likely to have been reported to the authorities. In contrast, incidents of fraud referred to the NFIB by Action Fraud, Cifas and UK Finance will mostly tend to be focused on cases at the more serious end of the spectrum, as by definition they will only include crimes that the victim considers serious enough to report to the authorities or where there are viable lines of investigation.

As a result, fraud offences referred to the authorities make up a relatively small proportion of the overall volume of fraud. This is supported by findings from the CSEW, which suggests that less than one-fifth (17.3%) of incidents of fraud either come to the attention of the police or are reported by the victim to Action Fraud (Table E7, year ending March 2017).

Further information on each of the data sources and the differences between them can be found in Section 5.4 of the User guide and also in the Overview of fraud and computer misuse statistics article.

No change in fraud measured by CSEW

New questions on fraud were introduced to half of the CSEW sample from October 2015 and increased to a full sample from October 2017. We can look at changes in these estimates over the last two years. However, as this comparison is based on two data points only, caution must be taken in drawing conclusions about trends at this early stage.

Results for the survey year ending December 2017 show no change in fraud offences when compared with the previous year (3.2 million offences). The only category of fraud to show a significant change was “other fraud” (down 64%, from 97,000 to 35,000 offences), which covers offences such as investment fraud or charity fraud. Over half of fraud incidents for the latest survey year were cyber-related3 (56% or 1.3 million incidents) (Table E2).

Table 6: Crime Survey for England and Wales fraud - number of incidents for year ending December 2016 and year ending December 2017 with percentage change1,2

| England and Wales | Adults aged 16 and over | |||

| Offence group | Jan '16 to Dec '16 | Jan '17 to Dec '17 | Percentage change and significance3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of incidents (thousands) | ||||

| Fraud | 3,480 | 3,241 | -7 | |

| Bank and credit account fraud | 2,454 | 2,332 | -5 | |

| Consumer and retail fraud4 | 827 | 813 | -2 | |

| Advance fee fraud | 102 | 61 | -41 | |

| Other fraud | 97 | 35 | -64 | * |

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 17,500 | 20,974 | ||

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | ||||

| 1. New victimisation questions on fraud were incorporated into the CSEW from October 2015. Up to the year ending September 2017 the questions were asked of half the survey sample. From October 2017 onwards the questions are being asked of a full survey sample. | ||||

| 2. In March 2018 the new CSEW estimates on fraud were assessed by the Office for Statistics Regulation against the Code of Practice for Statistics and were awarded National Statistics status. | ||||

| 3. Statistically significant change at the 5% level is indicated by an asterisk. | ||||

| 4. Non-investment fraud has been renamed as 'Consumer and retail fraud' to reflect the corresponding name change to the Home Office Counting Rules from April 2017. | ||||

Download this table Table 6: Crime Survey for England and Wales fraud - number of incidents for year ending December 2016 and year ending December 2017 with percentage change^1,2^

.xls (39.4 kB)Further findings from the CSEW fraud and computer misuse questions for the year ending December 2017 are presented in Tables E1 and E2.

Recorded crime also shows no change in fraud offences

The recorded crime series incorporates fraud offences collated by the NFIB from Action Fraud, Cifas and UK Finance4 and referred to the police for investigation. There was a similar volume of fraud offences recorded in England and Wales in the year ending December 2017 (639,457 offences) compared with the previous year (639,476 offences).

Fraud offences recorded by the NFIB have shown no change in the last year following increases over the previous four years

England and Wales, year ending March 2012 to year ending December 2017

Source: Action Fraud, National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB)

Download this chart Fraud offences recorded by the NFIB have shown no change in the last year following increases over the previous four years

Image .csv .xlsAlthough there was no overall change, differences were shown in the number of offences recorded in the last year, as reported separately by Action Fraud, Cifas and UK Finance. Overall offences showed:

- Action Fraud rose by 10% (up to 273,598 offences)

- Cifas fell by 7% (down to 283,284 offences)

- UK Finance fell by 6% (down to 82,575 offences)

The falls reported by both Cifas and UK Finance were due largely to a volume decrease in “banking and credit industry fraud", with UK Finance showing a fall of 6% (to 82,575 offences), and Cifas showing a fall of 5% (to 244,968 offences). This latest decrease reported by Cifas follows a period of increases seen in this type of fraud, and is driven largely by a decrease in “cheque, plastic card and online bank accounts fraud” (down 5% to 169,504 offences).

Cifas also reported a 3% decrease in the latest year in the number of incidents of “application fraud” referred to NFIB. This includes opening up an account using fake or stolen documents in someone else’s name. Again, this latest decrease in application fraud reported by Cifas follows previous large rises and is thought to reflect a return to normal levels after a spike in reporting in September 2016, as well as banks taking more preventative measures, in turn resulting in fewer fraudulent applications getting through the screening process.

The increase in offences reported to Action Fraud was driven largely by volume increases in “advance fee payment fraud" (up 32% to 52,469 offences)5 and “consumer and retail fraud” (up 4% to 105,921 offences). These are in contrast with the CSEW findings indicating no change in these fraud types and may be explained, in part, by differences in the coverage of the two sources.

Some caution must also be taken in interpreting this latest rise. Action Fraud recorded lower than normal monthly volumes of fraud offences between July 2015 and April 2016, following the company contracted to provide the call centre service going into administration6. Volumes have recovered but because the lower-volume months form part of the comparator year (year ending December 2016), the latest figure will have been influenced by this issue, albeit to a lesser extent than seen previously.

A full breakdown of the types of fraud offences referred to the NFIB by Action Fraud, Cifas and UK Finance in the latest year is presented in Table A5 and a definition of terms is provided in the User guide.

A police force area breakdown of Action Fraud data based on where the individual victim lives, or in the cases of businesses, where the business is located, is available from the year ending March 2016 (Table E3). The latest data show there was generally less variation in rates of fraud by police force area than for most other types of crime, although rates for force areas in southern England were generally a little higher than those among force areas in Wales or northern England.

Additional administrative data indicate a rise in card and bank account fraud

Additional data collected by UK Finance via their CAMIS system provide a broader range of bank account and plastic card frauds than those referred to the NFIB. These data are able to capture card fraud not reported to the police for investigation8. As a result, they provide a better picture of the scale of bank account and plastic card fraud in the UK, which helps to bridge the gap between the broad coverage provided by the CSEW and the narrower focus of offences referred to the NFIB. Most of the additional offences covered in the CAMIS data fall into the category of “remote purchase fraud”9 and fraudulent incidents involving lost or stolen cards, which account for a high proportion of plastic card fraud that is excluded from the NFIB figures.

In the latest year, UK Finance reported 1.9 million cases of frauds (excluding Authorised Push Payments) on UK-issued cards, cheque fraud and remote banking fraud via CAMIS10, an increase of 3% from the previous year (Table F4). The introduction of chip card technology has forced fraudsters to change their methods of working and most of this increase is covered by offences falling into the category “lost or stolen cards”. This increase in incidents involving lost and stolen cards is related to an increase in distraction thefts, where fraudsters are stealing cards in shops and at cash machines, and courier scams, where victims are tricked into handing over their cards on the doorstep11.

In support of this, data on the nature of theft from the person offences from the CSEW for the survey year ending March 2017 indicate that credit cards were one of the most commonly stolen items during incidents of theft from the person (44%) and were stolen in a higher proportion of incidents than five years ago (23%).

Authorised Push Payment fraud is included in CAMIS data for the first time

Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud relates to cases where victims are tricked into sending money directly from their account to an account that the fraudster controls. APP is included for the first time in the UK Finance CAMIS data for the year ending December 2017. As this is a new data collection, it is not yet possible to make comparisons over time. The new data show that in the year ending December 2017, 43,875 cases of APP fraud were reported to UK Finance, pushing the total CAMIS volume to 2 million incidents of fraud

APP fraud can often involve significant sums of money and have adverse financial and emotional consequences for the victim. Unlike most other frauds, victims of APP fraud authorise the payment themselves and current legislation means that they have no legal protection to cover them for losses. UK Finance reported that £236 million was lost through such scams in 201712. The majority of victims (88%) were retail consumers, losing an average of £2,784, and the remainder were businesses who lost on average £24,355 per case. These new data were produced in response to investigations by the Payment Systems Regulator (PSR) into a Super-complaint received from the consumer group Which? in 2016. Following the Super-complaint, the PSR, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the payments industry (represented by UK Finance) have developed an ongoing programme of work to reduce the harm to consumers from APP scams13.