1. Other pages in this release

Other commentary from the latest labour market data can be found on the following pages:

2. Main points

July to September 2020 estimates show a large increase in the unemployment rate and a record number of redundancies, while the employment rate continues to fall.

Although decreasing over the year, total hours worked had a record increase from the low levels in the previous quarter, with the July to September period covering a time when a number of coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown measures were eased.

The UK employment rate was estimated at 75.3%, 0.8 percentage points lower than a year earlier and 0.6 percentage points lower than the previous quarter.

The UK unemployment rate was estimated at 4.8%, 0.9 percentage points higher than a year earlier and 0.7 percentage points higher than the previous quarter.

The UK economic inactivity rate was estimated at 20.9%, 0.1 percentage points higher than the previous year but largely unchanged compared with the previous quarter.

The total number of weekly hours worked was 925.0 million, down 127.6 million hours on the previous year but up a record 83.1 million hours compared with the previous quarter.

The data in this bulletin come from the Labour Force Survey, a survey of households. It is not practical to survey every household each quarter, so these statistics are estimates based on a large sample.

4. Employment

Figure 1: The employment rate for all people decreased by 0.8 percentage points on the year, and decreased by 0.6 percentage points on the quarter, to 75.3%

UK employment rates (aged 16 to 64 years), seasonally adjusted, between January to March 1971 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 1: The employment rate for all people decreased by 0.8 percentage points on the year, and decreased by 0.6 percentage points on the quarter, to 75.3%

Image .csv .xlsEmployment measures the number of people aged 16 years and over in paid work and those who had a job that they were temporarily away from. The employment rate is the proportion of people aged between 16 and 64 years who are in employment.

The estimated employment rate for people aged between 16 and 64 years had generally been increasing since early 2012, largely driven by an increase in the employment rate for women. However, there has been a decrease since January to March 2020, coinciding with the start of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (Figure 1).

For people aged between 16 and 64 years, for July to September 2020:

the estimated employment rate for all people was 75.3%; this is 0.8 percentage points down on the year and 0.6 percentage points down compared with the previous quarter (April to June 2020)

the estimated employment rate for men was 78.6%; this is 1.7 percentage points down on the year and 1.1 percentage points down on the quarter

the estimated employment rate for women was 71.9%; this is 0.1 percentage points up on the year but down 0.1 percentage points on the quarter

The single-month estimates and weekly estimates of the employment rate suggest that the rate has been falling throughout the three-month period.

The increase in the employment rate for women in recent years is partly a result of changes to the State Pension age for women, resulting in fewer women retiring between the ages of 60 and 65 years. However, since the equalisation of the State Pension age, the employment rate for women had continued to rise, though it has now decreased because of the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

Imputation used for the Labour Force Survey (LFS) was not designed to deal with the changes experienced in the labour market in recent months. Experimental work with adjusted methodology suggests the use of the existing methodology has little impact on the employment rate (less than 0.1 percentage points). Further information can be found in the section on Measuring the data.

Estimates for July to September 2020 show 32.51 million people aged 16 years and over in employment, 247,000 fewer than a year earlier. This was the largest annual decrease since January to March 2010.

Employment decreased by 164,000 on the quarter. This quarterly decrease was driven by men in employment, young people in employment (those aged 16 to 24 years), the self-employed and part-time workers, but was partly offset by an increase in full-time employees.

Age group

Figure 2: There has been a large decrease in the number of young people (those aged 16 to 24 years) in employment over the last quarter

UK employment level by age (16 years and over), seasonally adjusted, cumulative growth from July to September 2019, for each period up to July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 2: There has been a large decrease in the number of young people (those aged 16 to 24 years) in employment over the last quarter

Image .csv .xlsLooking more closely at the change in employment over the quarter by age group (Figure 2), it decreased for those aged 16 to 24 years by 174,000 to a record low of 3.52 million. There was also a combined decrease of 60,000 on the quarter for those aged 35 to 64 years, to 20.06 million. Meanwhile, the number of people in employment aged 65 years and over increased by 66,000 on the quarter to 1.32 million.

Full-time and part-time employees and self-employed

Figure 3: The number of full-time employees increased on the quarter while the number of part-time employees and self-employed people continued to decrease

UK quarterly changes for total in employment, full-time and part-time employees, full-time and part-time self-employed by sex (aged 16 years and over), seasonally adjusted, between April to June 2020 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 3: The number of full-time employees increased on the quarter while the number of part-time employees and self-employed people continued to decrease

Image .csv .xlsLooking more closely at the quarterly decrease in employment (Figure 3), it can be seen that this is driven by decreases in the number of part-time workers (down 158,000 on the quarter to 8.11 million) and self-employed people (down 174,000 to 4.53 million, with a record 99,000 decrease for women).

The quarterly decrease was partly offset by an increase in full-time employees, up by 113,000 on the quarter to a record high of 21.17 million. The increase in full-time employees was driven by women (up a record 165,000 on the quarter to 8.72 million), while men decreased by 53,000 to 12.45 million, the first quarterly decrease since March to May 2019.

Employment status on the LFS is self-reported, with people classifying themselves as being either an employee or self-employed. Labour market flows estimates show that the recent increases in the number of employees and decreases in the number of self-employed people have been driven, in part, by a movement of people from self-employed to employee status.

Between April to June 2020 and July to September 2020, the number of people who changed from reporting themselves as self-employed to an employee was 277,000, the highest level since records began in 2005. Of these, the number who had changed jobs had not increased from normal levels. Consequently, some of the fall in self-employment comes from an increase in the number of people who have changed to classifying themselves as an employee, even though they have not changed jobs.

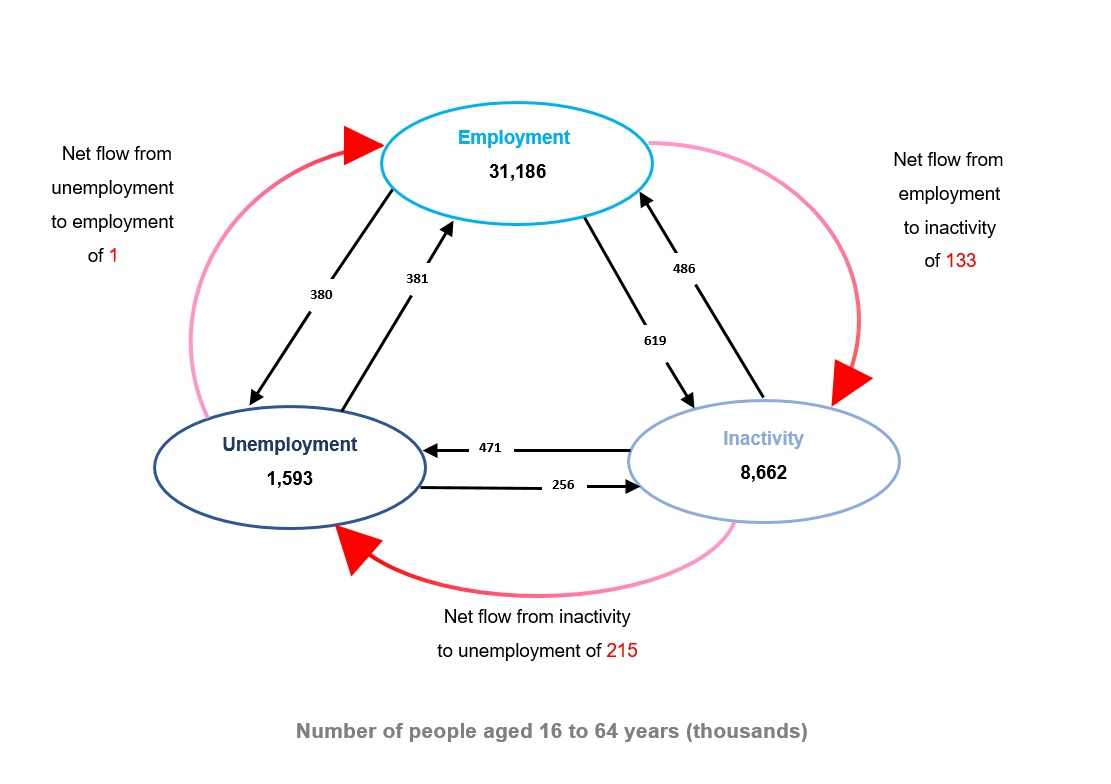

Figure 4: There was a record net flow of 214,000 into unemployment

UK flows between employment, unemployment and economic inactivity (seasonally adjusted), between April to June 2020 and July to September 20201

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- The figures in the bubbles are the total stocks in July to September 2020 (from dataset A02).

Download this image Figure 4: There was a record net flow of 214,000 into unemployment

.png (236.5 kB)Looking at estimates of flows between employment, unemployment and economic inactivity between April to June 2020 and July to September 2020 (Figure 4), there was a net flow of:

133,000 from employment to economic inactivity

1,000 from unemployment to employment

215,000 from economic inactivity to unemployment; the largest net flow from economic inactivity to unemployment on record

The net flow into unemployment was 214,000; the largest net flow into unemployment on record. This was driven by those moving from economic inactivity to unemployment, which contrasts with the small net flow from unemployment to economic inactivity seen in April to June 2020.

Figure 5: Job moves because of redundancy or dismissal are at a record high

UK job-to-job flows by reason (people aged 16 to 69 years), not seasonally adjusted, between July to September 2015 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- Includes a small number of people who took early retirement from their previous job or retired at or after State Pension age.

- Includes those whose temporary job came to an end or who left their previous job for health reasons, education or training purposes or some other reason. It also includes those who did not provide a reason

Download this chart Figure 5: Job moves because of redundancy or dismissal are at a record high

Image .csv .xlsLabour market flows estimates show that the number of people aged 16 to 69 years, who moved job between April to June 2020 and July to September 2020 because of redundancy or dismissal was 106,000 (Figure 5), the highest level since records began in 2001. Meanwhile, the number of people who moved job between these periods because of resignation was 105,000, the lowest level since January to March 2009.

Employment by industry and occupation

Looking at the change in employment by industry over the year to July to September 2020, the largest annual decreases were observed in accommodation and food services (down 261,000 on the year to 1.56 million) and manufacturing (down 230,000 on the year to 2.77 million). More information is available in Dataset EMP13.

The National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC) is partially derived from the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) and so can provide an indicator of changes in employment by broad occupation type. Over the year to July to September 2020, the number of people employed in higher managerial and professional, lower managerial and professional, and intermediate occupations increased. However, the number of small employers and own account workers and those employed in lower supervisory and technical, semi-routine, and routine occupations decreased. See Dataset EMP11 for more information.

The largest annual decrease was for small employers and own account workers (down 383,000 on the year to 3.10 million) and the second-largest decrease was in routine occupations (down 279,000 on the year to 2.53 million). This may indicate that these types of occupation have been most affected by the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

Employment by nationality and country of birth

Figure 6: There has been a record annual decrease in the number of non-UK nationals from the EU in employment in the UK

UK employment by nationality (not seasonally adjusted), people aged 16 years and over, between July to September 2000 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- The EU series is based on the current membership of the EU; for example, Poland is included in the EU series throughout the entire time series, although Poland did not join the EU until 2004.

Download this chart Figure 6: There has been a record annual decrease in the number of non-UK nationals from the EU in employment in the UK

Image .csv .xlsThe number of non-UK nationals from the EU working in the UK had increased between 2010 and 2016 but had been largely flat since then (Figure 6). Meanwhile, the number of non-UK nationals from outside the EU working in the UK had been largely flat since 2010 with a slight increase since 2017. However, in July to September 2020, the number of non-UK nationals from the EU decreased by a record 364,000 on the year to 1.87 million, while the number of non-UK nationals from outside the EU decreased by 65,000 to 1.29 million, the first annual decrease since October to December 2017.

Figure 7: There have been record decreases in the number of people in employment born in the EU and outside the EU

UK employment by country of birth (not seasonally adjusted), people aged 16 years and over, between July to September 2000 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- The EU series is based on the current membership of the EU; for example, Poland is included in the EU series throughout the entire time series, although Poland did not join the EU until 2004.

Download this chart Figure 7: There have been record decreases in the number of people in employment born in the EU and outside the EU

Image .csv .xlsThe number of non-UK born people working in the UK who were born in EU countries had been largely flat since 2016, while those who were born outside the EU had been increasing steadily since 2010 (Figure 7). However, in July to September 2020, there were record annual decreases both for those born in EU countries (down 386,000 to 1.98 million) and for those born outside the EU (down 208,000 to 3.19 million).

Decreases in the numbers of non-UK workers are similarly reported in the Business Impact of Coronavirus Survey (BICS), a survey of employers.

Hours worked

Since estimates began in 1971, up until the introduction of the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown measures, total hours worked by women had generally increased, reflecting increases in both the employment rate for women and the UK population. In contrast, total hours worked by men had been relatively stable because of falls in the employment rate for men, and increases in the share of part-time working, roughly offset by population increases.

Workers temporarily absent from a job as a result of the coronavirus pandemic would still be classed as employed; however, they would be employed working no hours. This directly impacted the total actual hours worked in July to September 2020. Since the average actual weekly hours are the average of all in employment, those temporarily absent from a job also impacted on those estimates. With the easing of lockdown restrictions in July and August and changes to the furlough scheme, the estimates show an increase for hours worked in July to September 2020 in comparison with the previous quarter, although the level is still well below pre-coronavirus levels.

Between April to June 2020 and July to September 2020, total actual weekly hours worked in the UK saw a record increase of 83.1 million, or 9.9%, to 925.0 million hours (Figure 8). There were record increases for both men's and women's total hours worked (up 46.8 million hours and 36.3 million hours respectively).

Average actual weekly hours worked saw a record increase of 2.7 hours on the quarter to 28.5 hours. The average weekly hours worked by men saw a record increase of 3.0 hours to 32.0 hours, while women's hours saw a record increase of 2.4 hours to 24.5 hours.

Figure 8: Total hours worked still low but showing signs of recovery

UK total actual weekly hours worked (people aged 16 years and over), seasonally adjusted, between July to September 2005 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 8: Total hours worked still low but showing signs of recovery

Image .csv .xlsImputation used for the Labour Force Survey was not designed to deal with the changes experienced in the labour market in recent months. Experimental work with adjusted methodology suggests that during the early stages of lockdown we were understating the full extent of the reduction in hours. However, now that hours are increasing, this has reversed so that the experimental methodology now suggests the actual number of hours are approximately 3% higher than stated.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Unemployment

Figure 9: The unemployment rate for all people increased by 0.9 percentage points on the year, and increased by 0.7 percentage points on the quarter, to 4.8%

UK unemployment rates (aged 16 years and over), seasonally adjusted, between January to March 1971 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 9: The unemployment rate for all people increased by 0.9 percentage points on the year, and increased by 0.7 percentage points on the quarter, to 4.8%

Image .csv .xlsUnemployment measures people without a job who have been actively seeking work within the last four weeks and are available to start work within the next two weeks. The unemployment rate is not the proportion of the total population who are unemployed. It is the proportion of the economically active population (those in work plus those seeking and available to work) who are unemployed.

Estimated unemployment rates for both men and women aged 16 years and over had generally been falling since late 2013 but have increased over recent periods (Figure 9).

For people aged 16 years and over, for July to September 2020:

the estimated UK unemployment rate for all people was 4.8%; this is 0.9 percentage points higher than a year earlier and 0.7 percentage points higher than the previous quarter

the estimated UK unemployment rate for men was 5.2%; this is 1.1 percentage points higher than a year earlier and 1.0 percentage point higher than the previous quarter

the estimated UK unemployment rate for women was 4.3%; this is 0.7 percentage points higher than a year earlier and 0.4 percentage points higher than the previous quarter

The single-month estimates of the unemployment rate suggest that the rate has been increasing throughout the three-month period.

Imputation used for the Labour Force Survey (LFS) was not designed to deal with the changes experienced in the labour market in recent months. Experimental work with adjusted methodology suggests the use of the existing methodology has little impact on the unemployment rate (less than 0.2 percentage points). Further information can be found in the section on Measuring the data.

For July to September 2020, an estimated 1.62 million people were unemployed, up 318,000 on the year and up 243,000 on the quarter. The annual increase was the largest since December 2009 to February 2010 and the quarterly increase was the largest since March to May 2009. The quarterly increase was mainly driven by men (up 178,000) and there were increases across all age groups.

Figure 10: Unemployment increased on the year, and on the quarter, for all age groups

UK unemployment by age (aged 16 years and over), seasonally adjusted, cumulative growth from July to September 2019, for each period up to July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 10: Unemployment increased on the year, and on the quarter, for all age groups

Image .csv .xlsLooking in more detail at the increase in unemployment by age group (Figure 10):

- those aged 16 to 24 years increased by 101,000 on the year, and 53,000 on the quarter, to 602,000

- those aged 25 to 49 years increased by 125,000 on the year, and 93,000 on the quarter, to 651,000

- those aged 50 to 64 years increased by 78,000 on the year, and a record 84,000 on the quarter, to 341,000

Figure 11: The number of people who have been unemployed for up to six months has been steadily increasing since the start of 2020

UK unemployment by duration (aged 16 years and over), seasonally adjusted, between July to September 2015 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 11: The number of people who have been unemployed for up to six months has been steadily increasing since the start of 2020

Image .csv .xlsThe annual increase in unemployment is driven by those unemployed for up to six months, up 224,000 on the year to 1.04 million (Figure 11). This is the largest annual increase for the short-term unemployed since June to August 2009. However, those unemployed for over 12 months have also increased by 30,000 on the year; the first annual increase for the long-term unemployed since June to August 2013. To estimate duration of unemployment, LFS respondents are asked how long they have been looking for work. Respondents are unlikely to discount short periods where they were not looking from this. Consequently, those that briefly stopped looking for work in the earlier stages of the pandemic, and were therefore classified as economically inactive, are likely to return to unemployment duration estimates in longer-term categories.

Labour market flows estimates show that, between April to June 2020 and July to September 2020, 471,000 people moved from economic inactivity to unemployment. This is the largest movement from economic inactivity to unemployment since July to September 2015.

Figure 12: The largest increase in unemployment was for those who were previously employed in accommodation and food service activities

UK unemployment by industry1 of last job (aged 16 years and over), not seasonally adjusted, July to September 2019 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- Industry based on Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) 2007.

Download this chart Figure 12: The largest increase in unemployment was for those who were previously employed in accommodation and food service activities

Image .csv .xlsLooking at unemployment by industry of last job, there were increases for all industries between July to September 2019 and July to September 2020 (Figure 12). The largest increase was for those previously employed in accommodation and food service activities (up 56,000 on the year to 161,000). The second-largest increase was for those previously employed in professional, scientific and technical activities (up 40,000 on the year to 84,000). The highest level of unemployment in July to September 2020 was for those previously employed in wholesale, retail and repair of motor vehicles (191,000).

The Claimant Count (Experimental Statistics)

These Claimant Count statistics relate to 8 October 2020. Enhancements to Universal Credit as part of the UK government's response to the coronavirus mean that an increasing number of people became eligible for unemployment-related benefit support, although still employed.

Consequently, changes in the Claimant Count will not be wholly because of changes in the number of people who are unemployed. We are not able to identify to what extent people who are employed or unemployed have affected the numbers.

The Claimant Count is an Experimental Statistic that seeks to measure the number of people claiming benefit principally for the reason of being unemployed.

To achieve this, the Claimant Count has generally been a count of the appropriate benefits within the UK's current benefit regime that best meet that criteria. Currently this is a combination of claimants of Jobseeker's Allowance (JSA) and claimants of Universal Credit (UC) who fall within the UC "searching for work" conditionality.

Those claiming unemployment-related benefits (either UC or JSA) may be wholly unemployed and seeking work, or may be employed but with low income and/or low hours, that make them eligible for unemployment-related benefit support.

Under UC a broader span of claimants became eligible for unemployment-related benefit than under the previous benefit regime. During the roll-out of UC since 2013, movements in the Claimant Count have been significantly affected by this expanding eligibility, rather than labour market conditions. This impact has led to the Claimant Count being reclassified to an Experimental Statistic.

As part of the UK government's response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, a number of enhancements were introduced to UC. These may have increased the number of employed people eligible for UC through their earnings falling below income thresholds.

Such claims will generally fall within the work search conditionality within UC.

Consequently, while some of any movement in the Claimant Count would be because of changes in the number of people who are out of work, a certain amount of the movement will be because of changes in the number of people in work who are eligible for UC as part of the government response. We are not able to identify to what extent these two factors have affected the numbers.

The Claimant Count dropped slightly in October 2020 to 2.6 million (Figure 13). This represents a monthly decrease of 1.1% and an increase of 112.4%, or 1.4 million, since March 2020.

Figure 13: UK Claimant Count level has increased by 112.4% since March 2020

UK Claimant Count, seasonally adjusted, between January 2008 and October 2020

Source: Department for Work and Pensions

Download this chart Figure 13: UK Claimant Count level has increased by 112.4% since March 2020

Image .csv .xls6. Economic inactivity

Economic inactivity measures people without a job but who are not classed as unemployed because they have not been actively seeking work within the last four weeks and/or they are unable to start work within the next two weeks. Our headline measure of economic inactivity is for those aged between 16 and 64 years.

Since comparable records began in 1971, the economic inactivity rate for all people aged between 16 and 64 years has generally been falling (although it increased during recessions). This is because of a gradual fall in the economic inactivity rate for women. This fall reflects changes to the State Pension age, resulting in fewer women retiring between the ages of 60 and 65 years, as well as more women in younger age groups participating in the labour market. Over recent years, the economic inactivity rate for men has been relatively flat (Figure 14).

Figure 14: The economic inactivity rate for all people increased by 0.1 percentage points on the year, but was largely unchanged on the quarter, to 20.9%

UK economic inactivity rate (all people aged 16 to 64 years), seasonally adjusted, between January to March 1971 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 14: The economic inactivity rate for all people increased by 0.1 percentage points on the year, but was largely unchanged on the quarter, to 20.9%

Image .csv .xlsFor people aged between 16 and 64 years, for July to September 2020:

the estimated economic inactivity rate for all people was 20.9%; this is up by 0.1 percentage points on the year but largely unchanged on the quarter

the estimated economic inactivity rate for men was 17.0%; this is up by 0.8 percentage points on the year and up by 0.3 percentage points on the quarter

the estimated economic inactivity rate for women was 24.8%; this is down by 0.7 percentage points on the year and down by 0.2 percentage points on the quarter

Estimates for July to September 2020 show 8.66 million people aged between 16 and 64 years not in the labour force (economically inactive). This was 46,000 more than a year earlier and 21,000 more than the previous quarter. The small quarterly increase was the result of increases for men, young people (those aged 16 to 24 years) and students, being largely offset by decreases for women, people aged 25 to 49 years, people looking after family and home, and people who were economically inactive for other reasons (further details follow).

Imputation used for the Labour Force Survey was not designed to deal with the changes experienced in the labour market in recent months. Experimental work with adjusted imputation methodology suggests the use of the existing methodology has little impact on the economic inactivity rate (less than 0.2 percentage points). Further information can be found in the section on Measuring the data.

Figure 15: Large quarterly increase in economic inactivity for those aged 16 to 24 years

UK economic inactivity by age (people aged 16 to 64 years), seasonally adjusted, cumulative growth from July to September 2019, for each period up to July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 15: Large quarterly increase in economic inactivity for those aged 16 to 24 years

Image .csv .xlsLooking at recent movements in economic inactivity by age (Figure 15), we see that the largest quarterly increase was for those aged 16 to 24 years, up 112,000 on the quarter to 2.74 million. Within this, there was a record quarterly increase of 66,000 for those aged 16 to 17 years, to a record high of 1.08 million. In contrast, the number of people aged 25 to 34 years decreased by 65,000 on the quarter, reaching a record low of 1.00 million.

In terms of the reason for economic inactivity, the quarterly increase was driven by students (up a record 231,000 on the quarter to 2.36 million) but partially offset by those looking after the family or home (down a record 143,000 on the quarter, to a record low of 1.62 million) and those who were economically inactive for other reasons (down a record 159,000 on the quarter to 1.13 million).

Other reasons include people who:

- are waiting the results of a job application

- have not yet started looking for work

- do not need or want employment

- have given an uncategorised reason for being economically inactive

- have not given a reason for being economically inactive

There was a record quarterly increase of 230,000 in the number of economically inactive people who did not want a job and, conversely, there was a record quarterly decrease of 209,000 for those who wanted a job.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Redundancies

The redundancy estimates measure the number of people who were made redundant or who took voluntary redundancy in the three months before the Labour Force Survey interviews; it does not take into consideration planned redundancies. So, in this release, the latest estimates relate to redundancies over the period from the beginning of April to the end of September 2020.

Figure 16: Redundancies increased by a record 181,000 on the quarter to reach a record high of 314,000

UK redundancies, people aged 16 years and over (not seasonally adjusted), between July to September 2005 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 16: Redundancies increased by a record 181,000 on the quarter to reach a record high of 314,000

Image .csv .xlsRedundancies increased in July to September 2020 by 195,000 on the year, and a record 181,000 on the quarter, to a record high of 314,000 (Figure 16). The annual increase was the largest since February to April 2009.

Figure 17: Redundancies have been increasing since June 2020

UK redundancies by week, people aged 16 years and over (seasonally adjusted), between January 2020 and September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Download this chart Figure 17: Redundancies have been increasing since June 2020

Image .csv .xlsExperimental weekly Labour Force Survey (LFS) estimates show that redundancies have been increasing since June 2020, with strong growth during the first two weeks of September 2020 (Figure 17).

Figure 18: The redundancy rate was highest for those aged 16 to 24 years

UK redundancy rate1 by age, people aged 16 years and over (not seasonally adjusted), July to September 2019 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- The redundancy rate is the ratio of the redundancy level for the given quarter to the number of employees in the previous quarter, multiplied by 1,000.

Download this chart Figure 18: The redundancy rate was highest for those aged 16 to 24 years

Image .csv .xlsIn July to September 2020, the overall redundancy rate, for people aged 16 years and over, was 11.3 per thousand employees. This was up from 4.3 per thousand in the same period a year earlier.

The redundancy rate increased for all age groups (Figure 18). Those aged 16 to 24 years had the highest redundancy rate of 17.2 per thousand (compared with 4.4 per thousand a year earlier) and those aged 35 to 49 years had the lowest redundancy rate of 8.9 per thousand (compared with 3.7 per thousand a year earlier).

Figure 19: Accommodation and food service activities had the highest redundancy rate

UK redundancy rate1 by industry2, people aged 16 years and over (not seasonally adjusted), July to September 2019 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- The redundancy rate is the ratio of the redundancy level for the given quarter to the number of employees in the previous quarter, multiplied by 1,000.

- Industry based on Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) 2007. Estimates for agriculture, fishing, energy and water are not shown because of small sample sizes.

Download this chart Figure 19: Accommodation and food service activities had the highest redundancy rate

Image .csv .xlsRedundancy rates increased for most industries between July to September 2019 and July to September 2020 (Figure 19). The largest rates were seen in accommodation and food service activities (23.6 per thousand), construction (21.6 per thousand) and other services (19.5 per thousand). Other services include arts, entertainment and recreation, households as employers, and other service activities such as personal service activities and repair of computers, personal, and household goods. Redundancy rates for public administration and defence (2.0 per thousand), education (3.3 per thousand) and human health and social work activities (3.4 per thousand) were little changed over the year.

Figure 20: The redundancy rate was highest in the West Midlands

UK redundancy rate1 by region of residence, people aged 16 years and over (not seasonally adjusted), July to September 2019 and July to September 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- The redundancy rate is the ratio of the redundancy level for the given quarter to the number of employees in the previous quarter, multiplied by 1,000.

Download this chart Figure 20: The redundancy rate was highest in the West Midlands

Image .csv .xlsIn the year to July to September 2020, the redundancy rate increased across all regions (Figure 20). The redundancy rate was highest in the West Midlands (16.0 per thousand, compared with 4.2 per thousand a year earlier) and lowest in Yorkshire and The Humber (5.9 per thousand, compared with 3.0 per thousand a year earlier).

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Employment in the UK data

Employment, unemployment and economic inactivity

Dataset A05 SA | Released 10 November 2020

Estimates of UK employment, unemployment and economic inactivity broken down into age bands.

Full-time, part-time and temporary workers

Dataset EMP01 SA | Released 10 November 2020

Estimates of UK employment including a breakdown by sex, type of employment, and full-time and part-time working.

Actual weekly hours worked

Dataset HOUR01 SA | Released 10 November 2020

Estimates for the hours that people in employment work in the UK.

Unemployment by age and duration

Dataset UNEM01 SA | Released 10 November 2020

Estimates of unemployment in the UK including a breakdown by sex, age group and the length of time people are unemployed.

Economic inactivity by reason

Dataset INAC01 SA | Released 10 November 2020

Estimates of those not in the UK labour force measured by the reasons given for economic inactivity.

Labour Force Survey sampling variability

Dataset A11 | Released 10 November 2020

Labour Force Survey (LFS) sampling variability (95% confidence intervals).

Labour Force Survey single month estimates

Dataset X01 | Released 10 November 2020

Labour Force Survey (LFS) single-month estimates of employment, unemployment and economic inactivity have been published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) since 2004. Not designated as National Statistics.

Labour Force Survey weekly estimates

Dataset X07 | Released 10 November 2020

Labour Force Survey (LFS) weekly estimates of employment, unemployment, economic inactivity and hours in the UK. All estimates are calculated from highly experimental weekly Labour Force Survey datasets.

9. Glossary

Actual and usual hours worked

Statistics for usual hours worked measure how many hours people usually work per week. Compared with actual hours worked, they are not affected by absences and so can provide a better measure of normal working patterns. For example, a person who usually works 37 hours a week but who was on holiday for a week would be recorded as working zero actual hours for that week, while usual hours would be recorded as 37 hours.

Economic inactivity

People not in the labour force (also known as economically inactive) are not in employment but do not meet the internationally accepted definition of unemployment because they have not been seeking work within the last four weeks and/or are unable to start work in the next two weeks. The economic inactivity rate is the proportion of people aged between 16 and 64 years who are not in the labour force.

Employment

Employment measures the number of people in paid work or who had a job that they were temporarily away from (for example, because they were on holiday or off sick). This differs from the number of jobs because some people have more than one job. The employment rate is the proportion of people aged between 16 and 64 years who are in employment. A more detailed explanation is available in our guide to labour market statistics.

Unemployment

Unemployment measures people without a job who have been actively seeking work within the last four weeks and are available to start work within the next two weeks. The unemployment rate is not the proportion of the total population who are unemployed. It is the proportion of the economically active population (that is, those in work plus those seeking and available to work) who are unemployed.

A more detailed glossary is available.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys10. Measuring the data

This bulletin relies on data collected from the Labour Force Survey (LFS), the largest household survey in the UK.

More quality and methodology information on strengths, limitations, appropriate uses, and how the data were created is available in the LFS QMI.

The LFS performance and quality monitoring reports provide data on response rates and other quality-related issues for the LFS.

Coronavirus

For more information on how labour market data sources are affected by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, see the article published on 6 May 2020, which details some of the challenges that we have faced in producing estimates at this time.

A blog published in July 2020 by Jonathan Athow, Deputy National Statistician for Economic Statistics, explains some of the differences between sources. An article and blog were published in October 2020 explaining the impact of the coronavirus on our Labour Force Survey.

Our latest data and analysis on the impact of the coronavirus on the UK economy and population are available on our dedicated coronavirus web page. This is the hub for all special coronavirus-related publications, drawing on all available data. In response to the developing coronavirus pandemic, we are working to ensure that we continue to publish economic statistics. For more information, please see COVID-19 and the production of statistics.

Impact of the coronavirus on data collection

The LFS design is based on interviewing households over five consecutive quarters. Generally, the first of these interviews, called Wave 1, takes place face-to-face, with most subsequent interviews, for Waves 2 to 5, conducted by telephone.

During March, we stopped conducting face-to-face interviews, instead switching to using telephone interviewing exclusively for all waves. This initially caused a significant drop in response.

New measures have been introduced to improve this, which have increased sample sizes, although they are still below normal LFS sample sizes.

Impact of the coronavirus on survey imputation methodology

The normal imputation for non-response to the LFS relies on rolling forward previous responses. Although this method is adequate under normal circumstances, it is not designed to deal with the changes experienced in the labour market in recent months. A new experimental imputation methodology has been researched to improve the measurement of the labour market at this time.

Because of time and system constraints, it has not been possible to fully integrate this methodology into the results within this release, but early indications suggest that:

there is little impact from the use of existing methodology on the headline measures of employment, unemployment and economic inactivity (less than 0.2 percentage points)

measures relating to hours in this release understate the increase in the actual number of hours worked by approximately 3%

We hope to include more information in later releases as this work develops.

Impact of the coronavirus on survey weighting methodology

Because of the impact on data collection, different weeks throughout the quarter have different achieved sample sizes. To mitigate this impact on estimates the weighting methodology was enhanced to include weekly calibration to ensure that samples from each week had roughly equal representation within the overall three-month estimate. This meant that any impacts seen from changes in the labour market in those weeks would be fully represented within the estimates.

Because of the suspension of face-to-face interviewing in March 2020, we had to make operational changes to the LFS, particularly in the way that we contact households for initial interview, which moved to a "by telephone" approach. These changes have resulted in a response where certain characteristics have not been as well represented as previously. This is evidenced in a change in the balance of type of household that we are reaching. In particular, the proportion of households where people own their homes in the sample has increased and rented accommodation households has decreased.

To mitigate the impact of this non-response bias we have introduced housing tenure into the LFS weighting methodology for periods from January to March 2020 onwards. While not providing a perfect solution, this has redressed some of the issues that had previously been noted in the survey results. More information can be found in an article Coronavirus and its impact on the Labour Force Survey.

Impact of government measures to protect businesses on the Labour Force Survey estimates

During late March, the government announced a number of measures to protect UK businesses. This included the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), also referred to as furloughing, and the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS).

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) classifies people within the labour market in line with International Labour Organization (ILO) definitions. Under the ILO definition employment includes employed persons "at work", that is, who worked in a job for at least one hour; and employed persons "not in work" because of temporary absence from a job, or to working time arrangements.

Under the current schemes it is likely that workers would have an expectation of returning to that job and would consider the absence from work as temporary. Therefore, those people absent from work under the current schemes would generally be classified as employed under ILO definitions.

In many cases, however, they would be employed but not in work. This absence would have an impact on the total hours worked. This would also be reflected in the average actual hours worked, which are based on the average hours per person employed, rather than the average hours per person at work. While actual hours would be significantly affected, there is unlikely to be any impact on usual hours, which would reflect normal working patterns.

After EU withdrawal

As the UK leaves the EU, it is important that our statistics continue to be of high quality and are internationally comparable. During the transition period, those UK statistics that align with EU practice and rules will continue to do so in the same way as before 31 January 2020.

After the transition period, we will continue to produce our labour market statistics in line with the UK Statistics Authority's Code of Practice for Statistics and in accordance with International Labour Organization (ILO) definitions and agreed international statistical guidance.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys11. Strengths and limitations

Uncertainty in these data

The estimates presented in this bulletin contain uncertainty.

The figures in this bulletin come from the Labour Force Survey (LFS), which gathers information from a sample of households across the UK rather than from the whole population. The sample is designed to be as accurate as possible given practical limitations such as time and cost constraints. Results from sample surveys are always estimates, not precise figures. This can have an impact on how changes in the estimates should be interpreted, especially for short-term comparisons.

As the number of people available in the sample gets smaller, the variability of the estimates that we can make from that sample size gets larger. Estimates for small groups (for example, unemployed people aged between 16 and 17 years), which are based on small subsets of the LFS sample, are less reliable and tend to be more volatile than for larger aggregated groups (for example, the total number of unemployed people).

In general, changes in the numbers (and especially the rates) reported in this bulletin between three-month periods are small and are not usually greater than the level that can be explained by sampling variability. Short-term movements in reported rates should be considered alongside longer-term patterns in the series and corresponding movements in other sources to give a fuller picture.

Comparability

The data in this bulletin follow internationally accepted definitions specified by the International Labour Organization (ILO). This ensures that the estimates for the UK are comparable with those for other countries.

An annual reconciliation report of job estimates is published every March comparing the latest workforce jobs (WFJ) estimates with the equivalent estimates of jobs from the Labour Force Survey (LFS).

The concept of employment (measured by the LFS as the number of people in work) differs from the concept of jobs, since a person can have more than one job and some jobs may be shared by more than one person. The LFS, which collects information mainly from residents of private households, is the preferred source of statistics on employment. The WFJ series, which is compiled mainly from surveys of businesses, is the preferred source of statistics on jobs by industry, since it provides a more reliable industry breakdown than the LFS. During the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic the LFS and WFJ series may have additional differences because a person's perception of their attachment to a job may differ from the business's perception of that job. It is also important to note that the LFS is based on interviews throughout the coverage period, whereas the WFJ series relates to a specific date. This difference can be significant in a labour market that is experiencing rapid changes.

Further information is available in A guide to labour market statistics.

| Level | Sampling variability of level¹ | Change on quarter | Sampling variability of change on quarter¹ | Change on year | Sampling variability of change on year¹ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment (000s, aged 16 years and over) | 32,507 | ± 207 | -164 | ± 174 | -247 | ± 260 |

| Employment rate (aged 16 to 64 years) | 75.3 | ± 0.5 | -0.6 | ± 0.4 | -0.8 | ± 0.6 |

| Average weekly hours | 28.5 | ± 0.2 | 2.7 | ± 0.2 | -3.7 | ± 0.3 |

| Unemployment (000s, aged 16 years and over) | 1,624 | ± 96 | 243 | ± 96 | 318 | ± 118 |

| Unemployment rate ( aged 16 years and over) | 4.8 | ± 0.3 | 0.7 | ± 0.3 | 0.9 | ± 0.3 |

| Economically active (000s, aged 16 years and over) | 34,130 | ± 195 | 79 | ± 168 | 71 | ± 247 |

| Economic activity rate (aged 16 to 64 years) | 79.1 | ± 0.4 | 0.0 | ± 0.4 | -0.1 | ± 0.5 |

| Economically inactive (000s, aged 16 to 64) | 8,662 | ± 180 | 21 | ± 155 | 46 | ± 227 |

| Economic inactivity rate (aged 16 to 64 years) | 20.9 | ± 0.4 | 0.0 | ± 0.4 | 0.1 | ± 0.5 |

| Redundancies (000s, aged 16 years and over) | 314 | ± 38 | 181 | ± 44 | 195 | ± 43 |

Download this table Table 1: Labour Force Survey sampling variability

.xls .csv

| Age group | Estimate | Sampling variability of estimate | Sampling variability of change on year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All people in employment (000s) | 16+ | 32,515 | ± 207 | ± 260 |

| All people employment rate | 16 to 64 | 75.3 | ± 0.5 | ± 0.6 |

| UK nationals in employment (000s) | 16+ | 29,352 | ± 239 | ± 303 |

| UK nationals employment rate | 16 to 64 | 75.2 | ± 0.5 | ± 0.6 |

| Non UK nationals in employment (000s) | 16+ | 3,161 | ± 144 | ± 186 |

| Non UK nationals employment rate | 16 to 64 | 76.1 | ± 1.7 | ± 2.1 |

| UK born people in employment (000s) | 16+ | 27,328 | ± 247 | ± 313 |

| UK born employment rate | 16 to 64 | 75.3 | ± 0.5 | ± 0.7 |

| Non UK born people in employment (000s) | 16+ | 5,176 | ± 170 | ± 218 |

| Non UK born employment rate | 16 to 64 | 75.4 | ± 1.4 | ± 1.7 |

| All unemployed people (000s) | 16+ | 1,703 | ± 96 | ± 118 |

| All people unemployment rate | 16+ | 5.0 | ± 0.3 | ± 0.3 |

| UK nationals unemployed (000s) | 16+ | 1,470 | ± 89 | ± 110 |

| UK nationals unemployment rate | 16+ | 4.8 | ± 0.3 | ± 0.4 |

| Non UK nationals unemployed (000s) | 16+ | 233 | ± 39 | ± 46 |

| Non UK nationals unemployment rate | 16+ | 6.9 | ± 1.1 | ± 1.3 |

| UK born unemployed people (000s) | 16+ | 1,344 | ± 80 | ± 101 |

| UK born unemployment rate | 16+ | 4.7 | ± 0.3 | ± 0.4 |

| Non UK born unemployed people (000s) | 16+ | 359 | ± 53 | ± 62 |

| Non UK born unemployment rate | 16+ | 6.5 | ± 0.9 | ± 1.1 |

| All economically inactive people (000s) | 16 to 64 | 8,569 | ± 180 | ± 227 |

| All people economic inactivity rate | 16 to 64 | 20.7 | ± 0.4 | ± 0.5 |

| UK nationals economically inactive (000s) | 16 to 64 | 7,797 | ± 174 | ± 218 |

| UK nationals economic inactivity rate | 16 to 64 | 20.9 | ± 0.5 | ± 0.6 |

| Non UK nationals economically inactive (000s) | 16 to 64 | 749 | ± 73 | ± 95 |

| Non UK nationals economic inactivity rate | 16 to 64 | 18.3 | ± 1.5 | ± 1.9 |

| UK born economically inactive people (000s) | 16 to 64 | 7,261 | ± 168 | ± 210 |

| UK born economic inactivity rate | 16 to 64 | 20.9 | ± 0.5 | ± 0.6 |

| Non UK born economically inactive people (000s) | 16 to 64 | 1,285 | ± 95 | ± 120 |

| Non UK born economic inactivity rate | 16 to 64 | 19.2 | ± 1.2 | ± 1.5 |