2. Main points

The preliminary estimate of gross domestic product (GDP) indicated that the UK economy grew by 0.6% in Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2016, up from 0.4% in the first three months of the year.

Aggregate output is now around 7.7% above its pre-downturn level, although the strength of this recovery is more muted on broader measures of economic well-being.

Goods accounted for around 75% of UK imports, but just 56% of UK exports in 2015, highlighting the growing importance of services to the UK export base. The deficit on trade in goods widened to 7.2% of GDP in Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2016, partly offset by a surplus of 4.7% of GDP on services.

Consumer price inflation rose to 0.5% in the year to June 2016, but remains near historical lows. Over the last year, the prices of import and energy intensive products have held back inflation.

Investment is the most variable component of GDP, adding considerably to the variation of output growth over the long-term, but moves broadly in parallel with measures of firm profits. Larger firms and firms in the production industries were the most investment intensive in 2014.

Recent falls in average weekly hours worked appear to reflect a normalisation of patterns of leave-taking among workers.

Notes:

- Quarter 1 refers to Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar), Quarter 2 refers to Quarter 2 (Apr to June), Quarter 3 refers to Quarter 3 (July to Sept), Quarter 4 refers to Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec).

3. Introduction

The preliminary estimate of gross domestic product (GDP) indicated that the UK economy grew by 0.6% in Quarter 2 2016, up from 0.4% in the first three months of the year. Aggregate output is now around 7.7% above its pre-downturn level, although the strength of this recovery is more muted on broader measures of economic well-being.

Against this backdrop and following the UK’s referendum on its membership of the European Union, this edition of the Economic Review examines recent trends in trade. It examines the relative importance of goods and services to the UK’s international trading position, showing that the deficit on trade in goods widened to 7.2% of GDP in Quarter 1 2016, partly offset by a surplus of 5.4% of GDP in services. It examines how the composition of trade in goods has changed over the last two decades and shows that while services account for a growing fraction of the UK’s exports by value, imports of goods account for a relatively stable and large portion of all UK imports. Finally, it shows the share of UK finished manufactures and semi-manufactures which are accounted for the EU and non-EU markets.

Secondly, it examines recent changes in the rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), which increased to 0.5% in the year to June 2016, but remains close to historic lows. It draws out the implications of movements in the exchange rate for the rate of consumer price inflation, showing that goods prices appear to be more sensitive to movements in exchange rates and presents an updated analysis of contributions to the rate of CPI inflation by products of different import intensity. This suggests that products which are relatively more import and energy intensive have held back inflation in recent months.

Recent trends in investment are also examined in this month's Review, highlighting the relationship between investment and profits. It finds that investment growth is the most volatile component of GDP growth – around twice as variable as GDP growth as a whole – but that this largely reflects the variation in firm profits during the economic cycle. Examining the ratio of capital acquisitions to gross operating surplus, it finds that larger firms and firms in the production industries were relatively more investment intensive in 2014.

This edition of the Economic Review also surveys two recent labour market developments. Firstly, it summarises the results of our analysis of the recent rise in self-employment. This concludes that the growth of self-employment since the onset of the economic downturn is better seen as an extension of a pre-existing trend. Self-employment accounted for just less than 15% of total employment in Quarter 1 2016, and a similar proportion of hours. This analysis concludes that much of the growth in self-employment over the past 15 years has been as a consequence of the growing prevalence of part-time self-employment among older workers who appear largely content with their labour market condition. This finding holds equally for mid-aged part-time self-employed women, although is less clear among younger men: it is among this group that evidence of under-employment is greatest.

Secondly, it builds on a previous analysis of average hours worked, examining how the ratio of actual to usual weekly hours changed over the course of the economic downturn and recovery. It concludes that reduced leave-taking boosted the length of the actual working week during the recovery, but that this effect had all but unwound by the start of 2016, following the re-emergence of pre-downturn levels of leave-taking. While the causes of this change are difficult to establish, this result is consistent with workers choosing not to take holiday during spells of uncertainty through job insecurity or financial necessity.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The preliminary estimate of gross domestic product (GDP) indicated that the UK economy grew by 0.6% in the second quarter of 2016, slightly faster than in the previous quarter, during which GDP is estimated to have grown by 0.4% (Figure 1). The growth in Quarter 2 2016 is the 14th consecutive quarter of expansion since the beginning of 2013, and is broadly equal to the average quarter-on-quarter growth rate over this period. Following a slowdown in GDP growth at the start of 2015, output has grown at a relatively steady pace in recent quarters, and was 2.2% higher in Quarter 2 2016 than in the same period a year earlier.

Figure 1: GDP quarter-on-quarter and quarter-on-same-quarter of previous year growth

Chained volume measure, percentage, Quarter 1 2012 to Quarter 2 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1: GDP quarter-on-quarter and quarter-on-same-quarter of previous year growth

Image .csv .xlsThe main drivers of quarter on quarter growth in Quarter 2 2016 were the services and production industries which grew by 0.5% and 2.1% respectively. The services industries – accounting for the largest part of the UK economy – continue to perform strongly, adding 0.4 percentage points to quarterly GDP growth over this period. Output growth was particularly strong in the arts, entertainments and recreation, and professional, scientific and technical industries over this period, although the business services and finance industries accounted for the largest part of services growth. This and earlier relatively strong outturns mean that the output of the services industries is now 11.2% above its pre-downturn peak (Figure 2).

Figure 2: GDP and main components

Chained volume measure, UK, Quarter 1 2008 to Quarter 2 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 2: GDP and main components

Image .csv .xlsThe strong performance of the services industries helped to raise GDP to around 7.7% above its pre-downturn level by Quarter 2 2016. While the recovery of output in the other main industrial groupings has been relatively slow, the strength of output growth from production during Quarter 2 2016 was notable. Although the mining and quarrying, and utilities industries grew relatively strongly over this period, much of the growth in production was driven by manufacturing, the output of which is at its highest level since Quarter 3 2008. In contrast, construction output growth has weakened over the last year, and the industry contracted by 0.4% in Quarter 2 2016.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Economic well-being

While estimates of GDP indicate that the economy has grown considerably over recent quarters, broader measures of the resources available to households, of net national disposable income and those measures expressed in per head terms suggest that this growth and the pace of the recovery has been more muted. Although estimates of GDP growth provide a guide to changes in total income, output and expenditure in the UK economy, ONS has published a broader range of statistics designed to capture economic well-being in the quarterly Economic Well-being release since December 2014. These measures go beyond traditional measures of GDP to account for some of its well-known limitations. Three of the headline indicators in this release include:

- GDP per head,

- net national disposable income (NNDI) per head

- real household disposable income (RHDI) per head

GDP per head measures domestic production in the economy per person – accounting for changes in the population – and therefore provides a simple measure of income per head. NNDI per head also accounts for changes in the population, and (a) subtracts the consumption of capital – the wear and tear resulting from assets being used in production – from GDP, capturing the net value of production and (b) includes a measure of net international investment income. This latter adjustment recognises that not all income generated by production in the UK will be payable to UK residents, and that UK residents may earn income on investments overseas. While GDP and NNDI are both measures of whole economy income (including households, corporations and government), RHDI per head examines the income that is available to the households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) sectors alone.

All three of these measures are shown in Figure 3 – indexed to their respective values in Quarter 1 2008. It suggests that both the depth of the downturn and the pace of the recovery were larger based on the GDP per head and NNDI per head measures. The former measure fell 7.3% between Quarter 1 2008 and Quarter 3 2009, while the latter had a peak to trough fall of close to 10% between Quarter 1 2008 and Quarter 1 2009. Both of these series have recovered gradually over the past eight years: GDP per head re-attained its pre-downturn level in the second half of 2015, although NNDI per head is yet to reach that yardstick. By contrast, RHDI per head was relatively stable during the economic downturn and recovery, only setting into a pattern of sustained growth from the start of 2014.

Figure 3: Three measures of economic well-being

Chained volume measure, Quarter 1 2005 to Quarter 1 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 3: Three measures of economic well-being

Image .csv .xlsFigure 3 also indicates that while the three measures grew at broadly the same rate through much of 2014 (indicated by the common upwards slope of these series over this period), their growth rates have diverged in recent periods. Between Quarter 1 2015 and Quarter 1 2016, RHDI per head and GDP per head grew by 4.6% and 1.3% respectively, while NNDI per head contracted by 0.9%. These relatively marked differences reflect some of the more detailed developments in the UK economy. In particular, the fall of NNDI relative to these other measures reflects the fall in the UK’s balance on income with the rest of the world: over this period, UK earnings overseas have grown less strongly than the earnings of overseas agents in the UK. This trend is largely accounted for by the fall in the relative rate of return on UK assets held overseas, and has been examined in previous editions of the Economic Review (April 2016 and July 2016) and other, stand-alone ONS analysis.

While the UK’s net income balance accounts for some of the recent growth differential between GDP and NNDI, the recent mix of growth among the GDP components has played a role in driving a wedge between the growth rates of GDP and RHDI. Figure 4 shows contributions to the growth of nominal GDP from the components of income. The recent easing of current price GDP growth – from 5.3% in the year to Quarter 2 2014 to 2.1% in Quarter 1 2016 – has primarily been driven by the declining contribution from the gross operating surplus of corporations and other income. By contrast, compensation of employees – which includes both wages and salaries and other deferred remuneration such as pension contributions – has maintained or increased its contribution to GDP growth, growing by 6.2% over the same period. As a result, while current price GDP growth has been moderating, the stronger performance of compensation of employees has served to support aggregate household nominal income over this period.

Figure 4: GDP quarter on quarter a year ago growth and contributions to growth by income components

Chained volume measure, percentage and percentage points, UK, Quarter 1 2010 to Quarter 1 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: GDP quarter on quarter a year ago growth and contributions to growth by income components

Image .csv .xlsAlongside the growth of compensation of employees, RHDI has recently been supported by the relatively low rate of inflation and by the growth of net social benefits. The low rate of inflation in recent quarters – as measured by both the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the average rate of price change for products consumed by households in the national accounts – has supported the real value of household incomes. Net social benefits other than benefits in kind – which are dominated by the payments of occupational pensions – grew by 14.1% between Quarter 1 2015 and Quarter 1 2016 – the fastest rate since 1992.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Trade

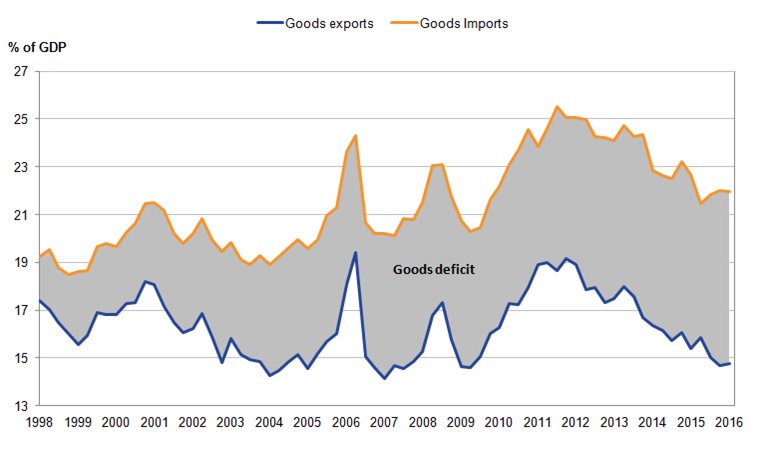

While the UK’s net income balance with the rest of the world – the earnings of UK agents on overseas assets, less overseas earnings on assets in the UK – has fallen quite sharply in recent years, the UK’s balance on trade has remained relatively stable. The UK has run a persistent deficit on trade – meaning that imports have exceeded exports – since 1998. This deficit has largely been driven by a deficit in trade in goods, which widened to 7.2% of GDP in Quarter 1 2016 – up by 5.4 percentage points relative to Quarter 1 1998 (Figure 5). However, the widening of the goods deficit has been partly offset by the rising trade surplus in services. As a consequence, the overall trade deficit remained relatively stable in recent years.

Figure 5: UK goods exports and imports as a percentage of nominal GDP

Current prices, Quarter 1 1998 to Quarter 1 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 5: UK goods exports and imports as a percentage of nominal GDP

.png (72.5 kB) .xls (32.3 kB)While the UK’s surplus on trade in services partially offsets the deficit on trade in goods, the latter still accounts for a majority of UK trade with the rest of the world. Goods accounted for around 75% of the value of all UK imports in 2015 – little changed from the average for the last 20 years (Figure 6), albeit slightly lower than between 1976 and 1995. By contrast, the share of exports accounted for by goods has been on a gradual downwards trajectory since the mid-1980s – falling from around 75% in 1985 to just 56% in 2015. This partly reflects changes in relative prices and the shift of the UK economy towards the services industries over this period. Taking imports and exports together, goods accounted for 65.7% of total UK trade in 2015 – broadly equivalent to its share in 2009, and around 13 percentage points lower than its peak share 30 years previously.

Figure 6: Current price shares of UK exports and imports accounted for by goods

Seasonally adjusted, percentage, UK, Quarter 1 1956 to Quarter 1 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 6: Current price shares of UK exports and imports accounted for by goods

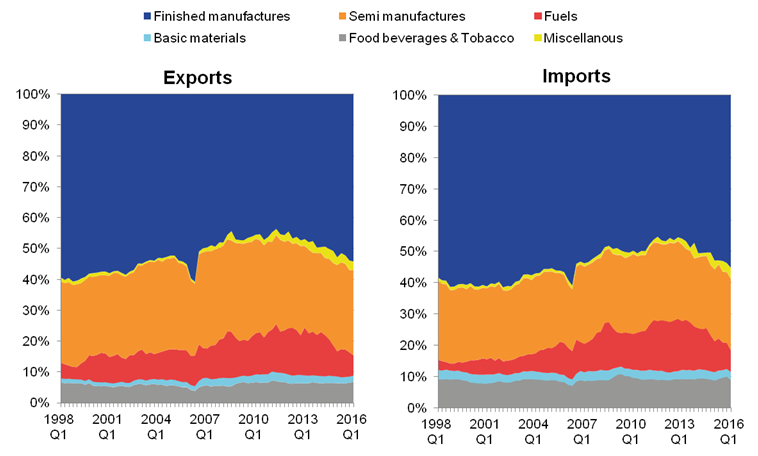

Image .csv .xlsAlongside these changes in the share of goods in total trade, the composition of goods traded by the UK has changed over the last 20 years (Figure 7). Most of UK trade in goods throughout this period was accounted for by manufactures: either finished manufactures – products which are ready to be used in production or for consumption – or semi-manufactures – which includes components for other products in final demand. The former category accounted for 55% of UK goods exports and a similar proportion of UK imports of goods in 2015. Semi-manufactures account for the second largest share on this basis – indicating that the UK’s supply chains are relatively well-integrated into the global economy – representing around 28% of goods exports in 2015, and a slightly smaller proportion of goods imports.

Figure 7: Composition of goods exports and imports

Current prices, seasonally adjusted, Quarter 1 1998 to Quarter 1 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- The large increase in the proportion of exports and imports of finished manufactures to the EU between Quarter 4 2005 and Quarter 3 2006 was due to missing in-trader intra-community (MTIC) fraud on goods

Download this image Figure 7: Composition of goods exports and imports

.png (90.6 kB) .xls (75.3 kB)Over time, some of the most striking changes in the composition of the UK’s trade in goods have been a consequence of changes in the importance of fuels, which in turn partly reflect changes in the price of oil. Between 1998 and 2013, the value of fuel imports grew as a share of total goods imports. Exports of fuels follow a broadly similar pattern: compressing the share of trade accounted for by manufactures between 1998 and 2012, before falling relatively sharply during 2014 and 2015. These trends are largely accounted for by relative movements in the price of fuels, changes in fuel quantities and the level of production in the UK’s domestic extractive industries – the output of which has fallen markedly over the long-term. The price of oil appears to have had a particularly important impact, with the value of fuel imports and exports following changes in the oil price from its relative lows in 1998 to its peak in 2008, before falling over the last 18 months in concert with the oil price.

Alongside these changes in the composition of trade in goods, there has also been a shift in the geographical patterns of UK goods trade. Figure 8 analyses exports of finished- (Panel A) and semi-manufactures (Panel B) to the EU and non-EU countries as a share of nominal GDP. Panel A indicates that immediately prior to the downturn, the value of UK exports of finished manufactures to the EU and the rest of the world were broadly comparable – each accounting for between 3% and 4% of UK GDP. During the recovery that has followed, exports of finished manufactures to the non-EU increased to between 4% and 5% of GDP, while the EU share has fallen slightly – likely reflecting the relative growth of demand in these different markets and the relative weakness of the economic recovery in the EU. Much of the growth in finished manufactures exports to the non-EU is accounted for by exports of cars to these markets which have doubled in value since the downturn.

Figure 8a: Exports of finished manufactures to EU and non-EU countries

Current prices, seasonally adjusted, as a percentage of gross domestic product, UK, 2007 Quarter 1 to 2016 Quarter 1, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 8a: Exports of finished manufactures to EU and non-EU countries

Image .csv .xls

Figure 8b: Exports of semi manufactures to EU and non-EU countries

Current prices, seasonally adjusted, as a percentage of gross domestic product, Quarter 1 2007 to Quarter 1 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 8b: Exports of semi manufactures to EU and non-EU countries

Image .csv .xlsExports of semi-manufactures account for a slightly smaller share of UK GDP than that of finished manufactures, but display some of the same trends. UK exports of these products to the EU were considerably higher than exports to the non-EU during the late 2000s – continuing a relatively stable gap evident since the late 1990s. However, during the economic recovery, UK exports to the EU have fallen relative to GDP, while exports to the non-EU have held their share of total output. As a result, the value of UK semi-manufactures exports to the EU and non-EU were broadly similar in 2015. To some extent, these trends reflect movements in relative prices and exchange rates, as well as changes in the underlying quantities. They also reflect the maturity of the UK’s trading relationship with the EU. As a result, UK trade with some major emerging markets, for example China, is still developing and therefore growing much faster.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Inflation

The impact of internationally traded goods prices on aggregate measures of UK inflation has been at the centre of policy-maker discussions since the result of the UK’s referendum on its membership of the European Union on 23 June 2016. The most recent Consumer Price Index (CPI) release provides information about inflation in the period to June 2016, and as a result of the timing of the data collection, it does not reflect any impact of the referendum result. The first inflation data from the post-referendum period will be the July CPI release, published on 16 August. A list of release dates for ONS’s main economic indicators that cover periods following the 23 June are located in the Annex.

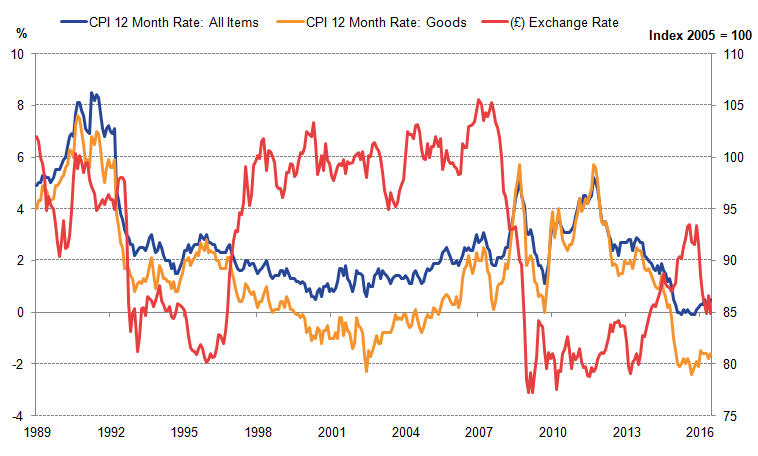

Inflation picked up slightly in the year to June 2016. The CPI inflation rate increased from 0.3% in the year to May, to 0.5% in the year to June – close to its rate in March 2016 and the joint highest rate since the end of 2014 (Figure 9). Transport prices made the largest upwards contribution to the rise in inflation – adding 0.13 percentage points of the 0.2 percentage point rise. This reflects a combination of higher fuel prices and higher air fares to European destinations in particular – possibly as a consequence of the Euro 2016 football tournament in France. These rises were partially offset by lower prices for furniture and furnishings and accommodation services. Core inflation – a measure which excludes relatively volatile prices of energy, food, alcohol and tobacco – increased from 1.2% in the year to May to 1.4% in the year to June.

Figure 9: Consumer price inflation

12-month rate, January 1989 to June 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 9: Consumer price inflation

Image .csv .xlsDespite this recent rise in inflation, Figure 9 makes it clear that price pressure remains close to historic lows. While the current rate of CPI inflation has lifted from the near-zero and negative rates observed during 2015, the current rate is lower than in almost every other month between 1989 and 2014 – only previously matched in May 2000. As set out in previous editions of the Economic Review, this is largely a consequence of the sharp reductions in the oil price during 2014 and 2015 feeding through to consumer prices. The price of oil fell from US $112 a barrel in June 2014 to a low of US $32 in January 2016. Since then it has recovered to a level of US $50 in June 2016.

Alongside this disinflationary effect from the price of oil, changes in the exchange rate are also thought to have had an impact on the rate of CPI inflation through its impact on the prices of imported goods and services. When sterling appreciates (depreciates) the cost of imported goods and services tends to fall (rise) and, partly as a consequence of the importance of trade in goods to the UK economy, the rate of goods price inflation appears to be particularly sensitive to changes in the exchange rate (Figure 10). During much of 2013 and 2014, sterling appreciated against the currencies of its major trading partners. As shown in Figure 10, this appreciation came alongside a marked fall in the rate of goods price inflation – resulting in the two series moving inversely. This mirrors the rise in goods prices which followed the depreciation of sterling between 2007 and 2009 – although on both occasions the precise effect of the exchange rate is difficult to identify because of simultaneous changes in the oil price.

Figure 10: CPI 12-month rate (all items), CPI 12-month rate (goods) and effective exchange rate index

January 1989 to June 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 10: CPI 12-month rate (all items), CPI 12-month rate (goods) and effective exchange rate index

.png (47.2 kB) .xls (49.7 kB)Since the result of the UK’s referendum on its membership of the European Union, the trade-weighted value of sterling has fallen by around 9.3% (as of 26 July). This follows a period of some prior depreciation – between early August 2015 and the referendum day itself – of around 7.3%, and while the sterling exchange rate has been quite volatile in recent weeks, policy-makers have been paying particular attention to the rate at which this depreciation might be expected to pass-through to the consumer.

Figure 11 updates analysis from a previous edition of the Economic Review, presenting contributions to the CPI from products grouped by their relative import intensities. Goods and services which consumers largely source from domestic producers are grouped together in a low import intensity group, while products which households purchase from abroad are grouped into higher import intensity groups. Energy products – which have considerable import content, but on which the price of oil has a particular impact – are grouped separately. Figure 11 suggests that following the previous substantial depreciation of sterling between 2007 and 2009, both the prices of imported and energy products made a considerable contribution to the rise in the rate of CPI inflation. Between 2013 and 2015, these effects reversed with the appreciation of sterling and the fall in oil prices, leading these same products to be a drag on the rate of price change. ONS will update this analysis in coming months as data becomes available from the post-referendum period, and as sterling’s depreciation since the start of 2016 starts to have an impact on price pressure.

Figure 11: Contributions to the CPI (All-items) 12-month inflation rate by product import intensity

Percent and percentage points, January 2007 to June 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 11: Contributions to the CPI (All-items) 12-month inflation rate by product import intensity

Image .csv .xls8. Investment

While household income and expenditure have supported economic growth over the last year, the contribution of investment to GDP growth has waned over this period. Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) – which comprises investment in fixed assets by corporations and government as well as investment in dwellings – added 1.1 percentage points to GDP growth in 2014, and around 0.6 percentage points in 2015 – but made a small, negative contribution to quarterly growth in Quarter 1 2016. Business investment – which comprises corporate investment in assets other than dwellings – has followed a similar trend: adding 0.5 percentage points to GDP growth in 2015 as a whole, but making negative contributions to quarter-on-quarter growth of 2.2 and 0.6 percentage points in Quarter 4 2015 and Quarter 1 2016 respectively. No official data on investment are yet available for the period following the UK’s referendum on its membership of the European Union: the first estimates for Quarter 2 (which includes the period immediately prior to and the week following the referendum) and Quarter 3 2016 will be published on 26 August and 25 November respectively.

Over the longer-term, investment spending has been the most variable component of GDP, making a substantial contribution to the variance of aggregate expenditure. Figure 12 provides a measure of variation in the annual growth rates of GDP and its components relative to their long-term averages: the larger (smaller) the coefficient of variation, the more variable (more consistent) the growth rate of a component has been over the 1949 to 2015 period. It shows that GDP is around as variable on average as household consumption – reflecting the relatively large proportion of aggregate expenditure which is accounted for by household spending and patterns in the co-variances of different components. Exports and imports also have similar, if slightly higher, coefficients of variation over this period, while the variability of government spending has been slightly higher still. Investment spending has the highest level of variability of this group and is around twice as variable relative to its average compared with GDP as a whole. In practice, this means that investment has been a relatively volatile component of GDP over the last half-century and, as it accounted for around 17% of aggregate spending in 2015, has made a considerable contribution to the variation of aggregate GDP.

Figure 12: Coefficient of variation of annual growth in GDP and its main expenditure components

Chained volume measure, 1949 to 2015, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 12: Coefficient of variation of annual growth in GDP and its main expenditure components

Image .csv .xlsThe variation of investment growth is widely attributed to the cyclical nature of capital spending and its relationship with economic sentiment. Investment tends to fall quite sharply at the onset of an economic downturn, as firms reduce their outgoings in the face of growing uncertainty, and tends to recover relatively quickly as the economy starts to grow again, as firms invest to increase their productive capacity to meet growing demand. Figure 13 shows the impact of investment during the first of these two phases, calculating the contribution of investment to the growth of GDP following the onset of three previous economic downturns. It indicates that over the seven quarters following the pre-downturn peak, lower investment had reduced GDP by a cumulative 2.6, 1.9 and 3.3 percentage points in the downturns starting in 1979, 1990 and 2008 respectively, reflecting the sharper contraction of GFCF compared with GDP as a whole. This impact is often considerable: between Quarter 1 2008 and Quarter 2 2009, GDP fell by 6.3%, of which 3.8 percentage points were accounted for by investment.

Figure 13: Cumulative contribution of Gross fixed capital formation to GDP growth during the past 3 downturns

Volume, percentage points, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 13: Cumulative contribution of Gross fixed capital formation to GDP growth during the past 3 downturns

Image .csv .xlsThe volatility of investment partly reflects the fortunes of the firms who undertake the majority of capital spending in the UK, as well as their perceptions of future demand and the potential for productivity-enhancing investments. Private corporations – which account for the majority of investment in the UK – usually undertake capital spending from retained profits or through external borrowing. As a result, stronger investment is possible during the upswing of the economic cycle when profits are relatively strong, and investment tends to fall during periods of weaker demand.

Figure 14 provides some evidence of this effect, plotting the ratio of business investment to aggregate profits. From this analysis, the marked fall in investment evident in Figure 13 and the volatility evident in Figure 12, are not as apparent when seen through the lens of firm profits. In particular, aggregate business investment remained a relatively stable portion of firm profits through the economic downturn and much of the recovery: ranging between 40% and 45% during this period. This suggests that in total, firms cut their capital expenditure by a similar proportion to their fall in profits. It also suggests a relatively marked fall in the share of profits that is re-invested over the early 2000s. Between 1997 and 2003, this measure of investment intensity was around 54% on average, but since 2004 investment as a share of profits has been around 40% to 45%. This sustained fall in the investment share of profits may signal changes in firm production functions, changes in the prices of capital goods or other aspects of firm behaviour. The most recent fall in investment intensity – between Quarter 3 2015 and Quarter 1 2016 – reflects the larger falls in business investment than in estimated profits over this period.

Figure 14: Investment intensity of private and public corporations (investment to profits ratio)

Current prices, Quarter 1 1997 to Quarter 1 2016, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 14: Investment intensity of private and public corporations (investment to profits ratio)

Image .csv .xlsTo examine recent changes in investment intensity in more detail, Figures 15 and 16 provide some information about the ratio of gross acquisitions to gross operating surplus of firms from the Annual Business Survey. Gross acquisitions of assets – from which disposals are subtracted to calculate total investment – captures a measure of the purchases made by firms during a period to increase their productive potential, and while there are differences in coverage and scope between the ABS and the National Accounts data presented in Figure 14, the results are suggestive.

Figure 15 indicates that the gross acquisition share of gross operating surplus varies depending on the size of the business. Measured on this basis, smaller firms had somewhat lower investment intensities than larger businesses between 2009 and 2014. The largest businesses – defined as those with 250 or more employees – are the most investment intensive on this basis. This will reflect a variety of factors determining investment behaviour, including access to financing, which tends to be easier for larger businesses than smaller businesses, as well as the nature of many smaller businesses, which may be concentrated in more labour-intensive industries.

Figure 15: Proportion of investment (acquisitions) to gross operating surplus by firm size

2009 to 2014, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Micro-sized firms have between 1 and 9 employees, small-sized firms have between 10 and 49 employees, medium-sized firms have between 50 and 249 employees, large-sized firms have 250 or more employees.

Download this chart Figure 15: Proportion of investment (acquisitions) to gross operating surplus by firm size

Image .csv .xlsWhile larger businesses have a higher investment intensity than smaller firms throughout this period, Figure 15 also indicates that there have been some notable changes in investment intensity for small and mid-sized firms. Medium-sized firms increased their investment intensity during 2011 and 2012, and small and micro-sized firms increased their investment intensity quite sharply in 2014. Large companies, by contrast, saw their investment intensity rise between 2010 and 2013 before falling back slightly in 2014.

The investment intensity of an organisation can also depend on the main industry in which it operates. Figure 16 shows that the production industry became the most investment intensive industry in 2013 – largely as a result of rising investment in the industry despite a contraction in its profits. The investment intensity of the services industries fell over the same period, despite strong growth in the industries’ profits.

Figure 16: Proportion of investment (acquisitions) to gross operating surplus by industry

2009 to 2014, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 16: Proportion of investment (acquisitions) to gross operating surplus by industry

Image .csv .xls9. Trends in self-employment

While short-term changes in investment are thought to provide a signal of firms altering their capacity to meet changing demand, over the long-term, changes in the pattern of investment can signal changes in the underlying production mix of firms. The strength of the UK’s labour market has been one of the defining characteristics of the recent economic recovery, and coupled with the relative weakness of investment for much of this period and the resulting slow growth of productivity, some commentators have suggested that the UK may be shifting towards a more labour-intensive mode of production.

The UK labour market continued in that pattern of strength in the three months to May 2016. The employment rate among those aged 16 to 64 increased to 74.4%, up from 74.1% in the three months to February 2016 and the highest employment rate since comparable records began. The unemployment rate among those aged 16 and above also continued to fall over this period – dropping 0.2 percentage points from 5.1% to 4.9%. The inactivity rate for those aged 16 and above also came down in the three months to May 2016 – falling from 36.7% to 36.3% compared with the same period a year earlier.

A large portion of this recent rise in employment has been as a consequence of stronger self-employment, which was the subject of a detailed analytical article that ONS published on 13 July 2016. This article shows that while the level of self-employment increased relatively strongly following the economic downturn, this development is better seen as an extension of a pre-existing trend. Figure 17 shows the share of all employment accounted for by self-employment increased from around 12% in the early 2000s, to just over 13% in 2008, before rising to around 15% by the start of 2016. Taking this period as a whole, the number of self-employed workers has risen from a low of 3.2 million in Quarter 4 2000 to around 4.7 million in Quarter 1 2016.

Figure 17: Share of self-employed workers in total employment and self-employed hours in total hours

Percent, Quarter 1 2000 to Quarter 1 2016, UK

Source: Labour Force Survey, cross sectional datasets, author’s calculations

Download this chart Figure 17: Share of self-employed workers in total employment and self-employed hours in total hours

Image .csv .xlsWhile the self-employment share of all employment has risen quite markedly since 2001, the share of self-employed hours in total hours has climbed more slowly (Figure 17), consistent with the relatively rapid growth of part-time self-employment over this period. While in absolute terms, part- and full-time self-employment each account for around half of the growth of self-employment over this period, the former mode has grown from a much lower base. As a result, the level of part-time self-employment grew by 88% between 2001 and 2015, compared with just 25% for the full-time mode. This growth in the share of part-time self-employed workers is notable, and accounts for much of the convergence of the self-employment worker and hours shares in Figure 17.

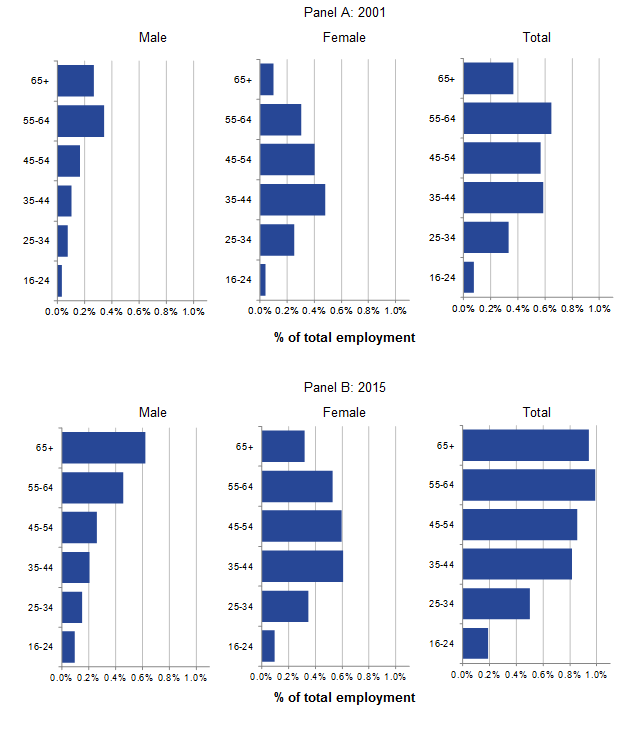

The prevalence of part-time self-employment has risen particularly strongly among older men and among older and mid-aged women. Figure 18 shows the rates of part-time self-employment among men, women and all workers in 2001 (Panel A) and 2015 (Panel B). It suggests that in 2001, this mode of employment largely comprised a mix of older male workers and mid-aged female workers: groups of workers who may have quite different reasons for choosing this employment status. These groups remain important in 2015, and Figure 18 highlights that much of the growth in this mode of employment over this period has been among older men and among older and mid-aged women.

Figure 18: Share of total employment by sex and age group accounted for by part-time self-employment

Percentage, 2001 and 2015, UK

Source: Labour Force Survey, cross sectional datasets, author’s calculations

Download this image Figure 18: Share of total employment by sex and age group accounted for by part-time self-employment

.png (22.8 kB) .xls (28.2 kB)As set out in the accompanying article, much of this growth in the prevalence of part-time self-employment has been among older workers who report that they are largely content with their part-time and their self-employed status, with little evidence of an accompanying rise in job search. For these workers, much of the growth in self-employment appears to be related to workers deferring retirement, managing their transition from the labour market in a different manner. Among mid-aged women there also appears to be a relatively high level of contentment with their labour supply choice, although among younger men the evidence is less clear: it is among this group that evidence of under-employment is greatest. Taken together, these trends suggest that the recent rise in self-employment is largely a structural feature of the UK economy, rather than a cyclical development that will unwind with greater labour demand.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys10. Analysis of usual and actual hours worked

Alongside judgements about the nature of the recent growth of self-employment, changes in the length of the average working week are central to estimates of the degree of spare capacity in the UK’s labour market. The average length of the working week in the UK has been falling over the long-term: dropping from around 33.1 to 31.5 hours per week between the three months to November 1995 and the three months to November 2009 – a trend that accelerated with the onset of the economic downturn in 2008. Following a recovery in average weekly hours worked between 2009 and 2013, their level started to fall again in 2014. These changes have quite marked consequences for estimates of slack in the UK economy: if they represent a structural shift towards shorter working weeks, then the productive potential of the economy may be lower than previously estimated. If, alternatively, they reflect cyclical patterns in labour supply, then the implications for the degree of spare capacity are lessened, suggesting greater potential for non-inflation accelerating growth.

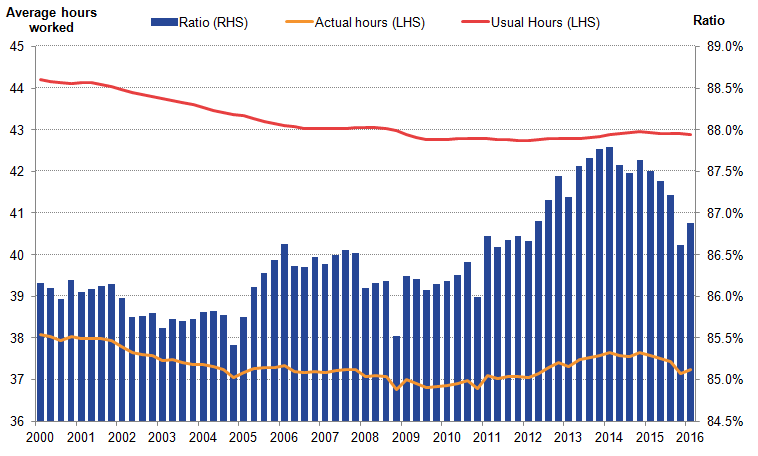

As noted in a previous edition of the Economic Review, headline trends in average actual hours are primarily driven by full-time workers, whose average actual hours are shown in Figure 19. Average actual hours worked for full-time workers rose by 45 minutes a week between 2009 and 2013. However, actual hours worked are affected by several factors – such as the degree of leave-taking, illness, and any industrial action – which result in actual hours worked differing from usual hours worked. Figure 19 also shows usual weekly hours for full-time workers, which tend to be higher than actual hours. In 2015, average actual weekly hours were 37.2 compared with average usual weekly hours of 42.9.

Figure 19: Average actual and usual hours worked, and the ratio of actual to usual hours worked

Full-time workers, Quarter 1 2000 to Quarter 1 2016, 4-quarter moving average, non-seasonally adjusted, UK

Source: Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- These data are not non-working-day adjusted, so can be affected by the changing reference period for respective quarters between years

Download this image Figure 19: Average actual and usual hours worked, and the ratio of actual to usual hours worked

.png (33.5 kB) .xls (32.8 kB)The distinction between actual and usual hours is particularly important as trends in the two have diverged since 2010. While actual hours rose between 2010 and 2013, usual hours remained broadly flat. These divergent trends are quite unusual, as between 2000 and 2008 the two series followed similar trends. Figure 19 also shows the ratio of actual to usual hours, and indicates these two series moved broadly together for much of the 2000s, resulting in a fairly stable ratio of around 86%. However, since the start of 2010, movements in actual hours have not been fully reflected in changes in usual hours – resulting in marked changes in the ratio over this period.

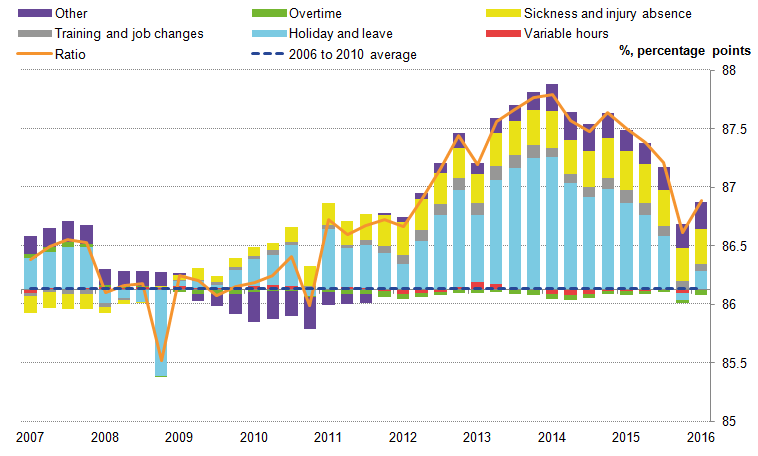

The different profiles for average actual and usual hours over recent years appear to be partly explained by patterns of leave taking. Figures 20a and 20b use data on the reasons that workers give for working more or less hours than usual in the Labour Force Survey. Figure 20a shows the average annualised number of hours worked less than usual per worker in each period by reason. These include regular leave – which makes up the largest component – maternity and paternity leave, bank holidays, sickness absence and other reasons. In Figure 20b, these average annualised estimates are indexed to their respective values in 2007 to give some sense of their relative growth rates in recent years.

Figure 20a: Annualised average hours worked less than usual by selected reasons

Full-time workers, Quarter 1 2007 to Quarter 1 2016, 4-quarter moving average, non-seasonally adjusted, UK

Source: Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- These data are not non-working-day adjusted, so can be affected by the changing reference period for respective quarters between years.

- Annualised figures are obtained by subtracting weekly actual hours worked from weekly usual hours worked, and multiplying the result by 52.

Download this chart Figure 20a: Annualised average hours worked less than usual by selected reasons

Image .csv .xls

Figure 20b: Annualised average hours worked less than usual by selected reasons

Full-time workers, Quarter 1 2007 to Quarter 1 2016, 4-quarter moving average, non-seasonally adjusted, UK

Source: Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- These data are not non-working-day adjusted, so can be affected by the changing reference period for respective quarters between years.

- Annualised figures are obtained by subtracting weekly actual hours worked from weekly usual hours worked, and multiplying the result by 52.

Download this chart Figure 20b: Annualised average hours worked less than usual by selected reasons

Image .csv .xlsFigure 20a indicates that other regular leave and holiday – which excludes parental and bank holiday leave – accounts for the largest portion of the difference between actual and usual hours for full-time workers – representing around 160 hours per worker year at the start of 2016. Sickness and injury absence and individuals who work variable hours accounted for smaller, if still substantial portions of this difference, of around 38 and 48 hours per worker year respectively. Figure 20b also suggests that the reasons for being absent from work have varied in their prevalence over recent years. It indicates that the prevalence of maternity and paternity leave has increased quite sharply since 2007 – albeit from quite a low base – while the average number of hours lost due to ill-health has fallen by around 20% over the same period. However, perhaps the largest and most substantial changes have been in regular leave-taking, which was lower throughout the economic downturn and through much of the recovery, and which only started to recover in 2014. This suggests that much of the variation in the ratio of actual to usual hours in recent years is due to patterns of regular leave.

This finding is largely confirmed by Figure 21, which examines changes in the ratio of actual to usual hours relative to its 2006 to 2010 average and isolates the contributions of different forms of leave taking. The ratio of actual to usual hours in 2014 was 1.5 percentage points higher than its 2006 to 2010 average, indicating that workers worked a larger portion of their usual hours over this period. Of this increase, 0.9 percentage points was accounted for by reduced holiday and leave taking, 0.3 percentage points were due to reduced ill-health absence and a further 0.1 percentage points were due to reduced training and job-moves. While the motivations for this development are difficult to establish with any certainty, this trend is consistent with workers choosing to supply more labour within their existing contracts than previously – possibly indicating a degree of insecurity at work, or a more general unwillingness to take leave on other grounds.

Figure 21: Contributions to the change in the ratio of actual to usual hours relative to 2006 to 2010

Full-time workers, Quarter 1 2007 to Quarter 1 2016, percentage points, four-quarter moving average, non-seasonally adjusted, UK

Source: Labour Force Survey

Notes:

- ‘Variable hours’ refers to those whose hours vary on a regular basis.

- Contributions may not sum due to rounding.

- These data are not non-working-day adjusted, so can be affected by whether the changing reference period for respective quarters between years

Download this image Figure 21: Contributions to the change in the ratio of actual to usual hours relative to 2006 to 2010

.png (26.5 kB) .xls (33.3 kB)However, the rise in the ratio of actual to usual hours had been largely reversed by the start of 2016 – mostly as a consequence of workers shifting back towards a more ‘normal’ pattern of leave taking. Figures 20 and 21 both indicate that average patterns of leave were largely re-established at the end of 2015, with the remaining elevation in the ratio due to a mix of lower sickness, training and other forms of absence. These trends suggest that part of the recent weakness of actual hours worked has been a consequence of the re-emergence of pre-downturn patterns of leave-taking. This unwinding of some of the broader effects of the economic downturn therefore suggests a continued reduction in the degree of slack in the labour market. Worker confidence and their financial circumstances appear to have recovered sufficiently to permit a greater degree of leave taking than during the downturn, when the average working week was unusually long. The strength of this unwinding and its impact on average hours worked makes judgements about the degree of spare capacity in the UK labour market more difficult.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys