In 2015 the UK public sector received £671 billion, spent £753 billion, borrowed £82 billion, had a current budget deficit of £46 billion and at the end of 2015 a debt of just over £1.6 trillion (or 84% of GDP)1.

So just what do all these numbers mean? Here, we explain.

First of all what is the public sector?

The public sector includes central government, local government, the Bank of England and other public corporations.

What does it do with money?

It receives and spends money continually throughout the year.

The money it receives mainly comes from taxes (such as income tax and VAT) and social contributions (such as National Insurance) but it also comes from rents, fines, licences and interest payments on money it has lent out.

The money it spends goes on two different areas:

- Current spending - the cost of running the country from day to day. This is the main area of spending and includes paying benefits (such as state pensions and child benefit), the costs of running local government and central government departments (such as health, education and defence), paying grants and paying the interest on the government’s debt.

- Capital spending - the net cost of investment. This is what the public sector spends on building assets like roads and buildings plus what it spends on providing grants to the private sector, minus what is gets from selling assets.

What happens if public sector income and spending do not match up?

If the public sector receives more than it spends, it is said to be in “surplus”.

In contrast when the public sector spends more than it receives it has to borrow the difference. When this happens the public sector is said to be in “deficit”.

However there are two common ways of looking at the deficit:

- The difference between the money it receives and current (or day to day) spending. This figure is called the “Current Budget Deficit” - £46 billion in 2015.

- The difference between the money it receives and current (or day to day) spending together with capital spending.This figure is called “Public Sector Net Borrowing” (PSNB) - £82 billion in 2015.

The most widely used figure when talking about the public sector deficit is the PSNB figure. So in this piece, when we use the term “the deficit” we will be referring to the PSNB figure.

UK public sector spending, income, surplus and deficit2, 1993 to 2014

Embed code

So is deficit the same as debt?

No. The difference between debt and deficit is that deficit represents the difference between income and spending at one point in time while debt represents the total amount of money owed, built up over a period of time. So reducing the deficit is not the same as reducing the debt.

To make this more clear, let’s imagine this:

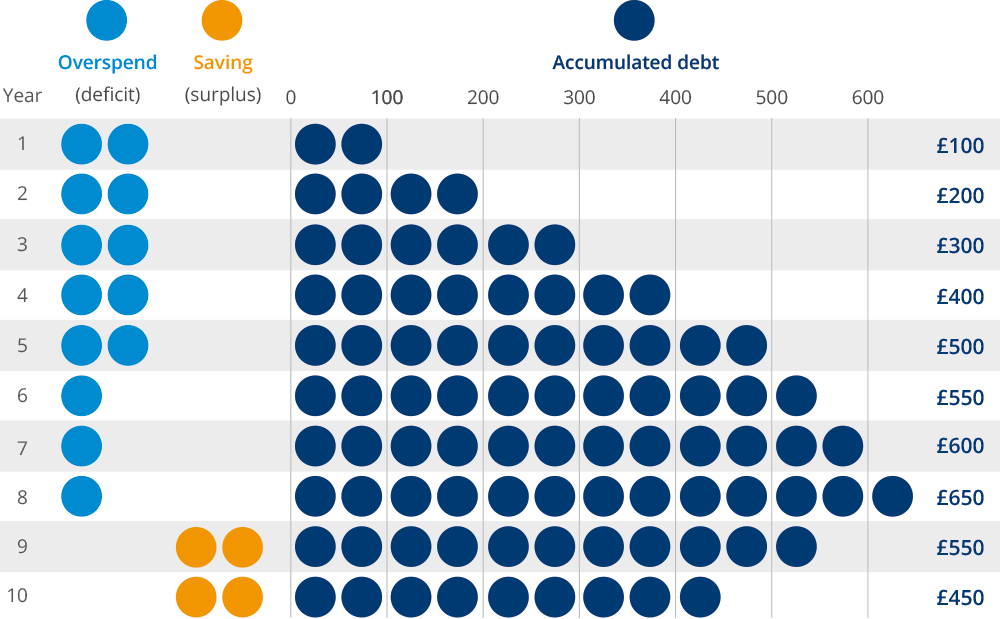

A person overspends by £100 for five years – this is a deficit of £100 for five years running with an accumulated debt of £500.

They then manage to only overspend by £50 for the next three years - this is a deficit of £50 for three years running with a total accumulated debt of £650.

They then manage to actually save £100 for two years - this is a surplus of £100 for two years running, reducing the total accumulated debt to £450.

So even though they reduced their deficit after five years and ran a surplus for the last two years, they are still left with a debt of £450.

Illustration of deficit, surplus and accumulated debt

So whenever the public sector has to borrow to fund its yearly spending plans (i.e. runs a deficit), it will normally lead to an increase in the overall level of debt.3 Even if the deficit is reduced, the debt continues to rise, just at a slower rate. The debt can be significantly reduced if the public sector starts running a surplus and uses this money to pay off accumulated debt.

UK public sector debt was £1.5 trillion andthe public sector deficit was £82 billion in 2015.

UK public sector debt and deficit4, 1993 to 2015

Embed code

Comparing the two lines we can see that while the deficit has been on a downward trend since 2009, the level of debt has been continually rising. This is mainly because the UK public sector continues to run a deficit – which has been adding to the overall level of debt.

But what about interest on the debt?

We must also remember that in the example above we assumed a 0% interest rate. In the real world the public sector debt comes with interest that needs to be paid every year and the bigger the debt, the bigger the interest payments. In the year 2000 the public sector spent £26 billion on paying the interest on the debt, by 2011 it had risen to £46 billion and in 2015 it spent £36 billion5.

UK public sector spending on debt interest was £36 billion in 2015.

So how can the UK afford this debt?

The debt figure may seem very large but we do need to consider it in context. This is why we often see it expressed as a percentage of UK GDP (Gross Domestic Product).

Think of it this way, if I say I borrowed £1 million last year that sounds like a lot of money. But if I then say that last year I produced goods and services valued at £10 million, the borrowing only amounts to 10% of what I actually produced. Because the amount I borrowed has been put into context, it sounds more reasonable.

The same concept applies when expressing the public sector debt as a percentage of GDP because GDP measures the total value of everything the UK produces. This concept is also useful (and often used) when talking about the deficit or any large items of public sector spending.

In 2015 the UK public sector debt stood at £1.6 trillion, this was equivalent to 84% of UK GDP.

UK public sector debt was 84% of GDP in 2015.

Footnotes:

- These figures, and all others used in this piece are for calendar years, not financial years.

- In the UK Public Sector Finances, the income measure is called 'revenue', the spending measure is the sum of 'total current expenditure', 'depreciation' and 'total net investment', and the deficit measure is 'Public Sector Net Borrowing'. All data are excluding public sector banks. Deficit/surplus figures have been rounded and may not be shown as the exact difference between spending and income.

- A deficit will not always lead to an increase in debt - only when the government chooses to fund it by adding to the overall level of debt.

- The debt measure shown here is Public Sector Net Debt, excluding public banks and the deficit measure is Public Sector Net Borrowing, excluding public banks.

- These are nominal figures.