1. Introduction

This article provides analysis specific to public service healthcare productivity for England and on a financial year basis. This additional analysis is included to provide a measure more comparable with other data available on the health service in England.

Released alongside this article are a healthcare productivity article produced on the traditional UK calendar year basis, providing an overview of productivity trends and information on how productivity is measured, as well as the annual UK total public service productivity estimates:

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Main points

In the financial year ending (FYE) 2018, healthcare productivity in England grew by 0.7%, down from the previous year’s figure of 2.0% and just below the average growth for the series of 1.0%.

Inputs growth of 1.7% in FYE 2018 was similar to growth in FYE 2017 but well below the average of 3.8% over the course of the series.

Quantity output growth slowed to 2.0% in FYE 2018, from 3.0% in FYE 2017, with a slowdown across all four components in the output measure.

The quality adjustment added 0.4 percentage points to output growth in FYE 2018 indicating improved service quality; this was a slightly greater quality adjustment than in FYE 2017.

Non-quality adjusted productivity increased by 0.3% in FYE 2018, making this the eighth consecutive year of growth, but also the slowest growth rate of the last eight years.

Revisions because of methodological improvements mean productivity has been revised down over the series, with average annual productivity growth between FYE 1996 and FYE 2017 being 0.1 percentage points lower in this year’s publication than last year’s.

3. Inputs

Inputs in the public service healthcare productivity measure are measured in volume terms and consist of three components:

labour, or staff inputs

goods and services inputs, which include the intermediate consumption of equipment used by healthcare providers, such as gloves and syringes; this component also includes GP-prescribed drugs, services provided by non-NHS organisations and agency staff costs

capital consumption, which covers the cost of depreciation of capital goods (items that are anticipated to be in use over several years, such as buildings and vehicles) over time

More information on how inputs are measured can be found in the Quality and Methodology Information and Sources and Methods Public Service Productivity Estimates: Healthcare (PDF, 328KB).

Labour inputs have grown faster than goods and services inputs for the last two years, in contrast to the rest of the time series

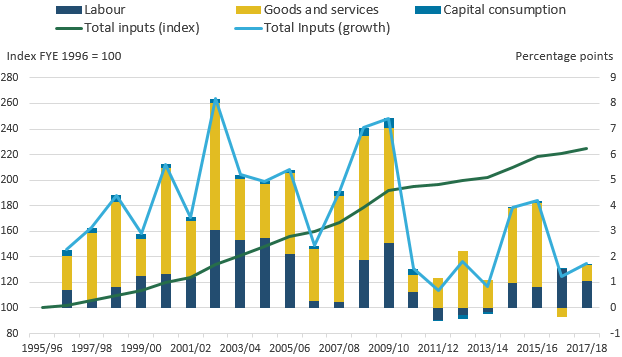

Figure 1a shows the growth in the two main components: labour, and goods and services inputs.

Figure 1a: Public service healthcare inputs quantity growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figure 1a shows the inputs growth by component before it is weighted by expenditure share.

- Capital consumption growth was not included in Figure 1a, due to its small expenditure weight, and therefore small impact on total inputs (see Figure 1b).

Download this chart Figure 1a: Public service healthcare inputs quantity growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Image .csv .xlsIn the financial year (April to March) ending (FYE) 2018, labour inputs grew by 2.3%, similar to the average growth rate over the whole period FYE 1996 to FYE 2018. This was slower than the previous year’s growth rate of 3.3% but was still the second-fastest growth in labour inputs in the 2010s.

Growth in labour inputs in FYE 2018 was because of increases in full-time equivalent staff numbers across a range of staff groups. Consistent with recent years, there was an outsized contribution to labour input growth from consultants1, where full-time equivalent staff numbers increased by 3.4% in FYE 2018, the same rate as in FYE 2017.

There were also substantial contributions to labour growth from the other large staff groups, including support to clinical staff and scientific, technical and therapeutic staff; although it is notable that full-time equivalent nursing staff numbers fell by 0.2% in FYE 2018. Growth in labour inputs was also limited by a fall in GPs and general practice staff numbers of 0.9%2.

It should be noted that, for the first time, NHS bank staff3 have been included in the labour measure from FYE 2016 onwards4. NHS bank staff fulfil a similar role to agency staff, working variable hours in response to demand. In FYE 2018, bank staff expenditure grew by 18.3%, although this was slower than the previous year’s rapid growth of 42.1%. Unfortunately, data are not available for earlier periods. The introduction of NHS bank staff results in an upward revision to labour inputs growth for FYE 2017 from 2.0% to 3.3%. More information on the effect of this and other changes can be found in Section 6: Revisions.

Not all workers in the NHS are included in the labour input measure. Agency staff are included in the goods and services element of inputs as, unlike NHS bank staff, agency workers are not employees of the health service.

The rise in NHS bank staff spending can be linked to a fall in agency staff spending, which followed the introduction of a cost-per-hour cap on agency staff, introduced in the English NHS in November 2015 and extended to all staff categories in April 2016. NHS England estimates agency staff costs are on average 20% higher than NHS bank staff costs and so has promoted the use of NHS bank staff in place of agency staff, including through an NHS Professionals campaign, launched in 2016, to encourage nurses to join staff banks.

The rise in expenditure on NHS bank staff in FYE 2017 and FYE 2018 was roughly offset by the fall in expenditure on agency staff, meaning the combined effect of these two staff groups on overall inputs was relatively small.

Because of a lack of data on the pay cost growth of NHS bank staff and agency staff, the volume measures for these inputs are produced using expenditure deflated by the pay cost inflation of substantive NHS staff. As we cannot confirm how different the pay growth of agency and NHS bank staff is from that of substantive NHS staff, the volume inputs measures for these staff groups are estimates.

In FYE 2018, goods and services inputs growth rebounded from a fall in FYE 2017, but still remained slow

In FYE 2018, goods and services inputs grew by 1.2%. This reversed a fall of 0.7% in FYE 2017 but was well below the average rate of 6.1% observed over the whole period FYE 1996 to FYE 2018.

Two important factors behind this trend were:

agency staff expenditure continued to fall substantially in FYE 2018, but slightly less than in FYE 2017

inflation recorded by the two most highly weighted deflators5 used in goods and services inputs was lower in FYE 2018 than FYE 2017, but still stronger than in FYE 2015 and FYE 2016

The goods and services inputs used in this article are revised relative to previous publications as they incorporate several changes to the deflators used to convert inputs expenditure into inputs volumes, including the introduction of the new NHS Cost Inflation Index (NHSCII). The NHSCII is produced to provide deflators that are more specific to the inflation in costs experienced by the NHS than whole-economy deflators such as the GDP deflator.

However, there are some important caveats with the use of the NHSCII, including that, for goods and services costs, the measures of price change used are not measured using data on the prices actually paid by the NHS, but instead use general economy data on the sorts of goods and services procured by the NHS. This is a particularly important issue in the case of drugs administered by NHS providers, where the best available price change measure is not specific to the sorts of drugs administered by NHS providers.

The deflators used affect the growth rates of goods and services inputs as inflation reduces the volume of inputs that can be purchased with any given amount of expenditure, and so stronger inflation will lead to slower goods and services inputs growth for any fixed rate of expenditure growth.

The deflator applied to the largest share of goods and services expenditure, a version of the NHSCII deflator for intermediate consumption of goods and services, experienced lower growth than the gross domestic product (GDP) deflator in FYE 2018. The NHSCII intermediate consumption deflator showed inflation of 0.9% compared with 1.7% for the GDP deflator. This resulted in faster growth in goods and services inputs than if the GDP deflator had been used and therefore slightly lower productivity growth.

More information on changes to deflators can be found in Section 6: Revisions and Methodological developments to public service productivity: healthcare.

In FYE 2018, total inputs growth was similar to FYE 2017 and the early-2010s

Figure 1b shows the contribution to the overall growth rate made by each of the three input components.

Figure 1b: Public service healthcare contributions to inputs growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figure 1b shows the inputs growth by component after weighting by their share of total expenditure.

Download this image Figure 1b: Public service healthcare contributions to inputs growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (31.4 kB) .xls (51.2 kB)The contribution of each element to inputs growth depends on both the growth rate of that element and its share of total expenditure. Over the period covered by the series, both goods and services, and labour inputs have had large shares of expenditure and seen substantial growth, and as a result have made large positive contributions to overall inputs growth. Because of its small share of expenditure, capital consumption has had a minor effect on overall inputs growth over the period.

Figure 1b shows that inputs grew by only 1.7% in FYE 2018, with all three input components contributing to this growth, although the contribution from capital consumption was relatively small because of its small share of expenditure.

Growth in healthcare inputs has slowed from an average of 5.4% annually in the 2000s to an average of 2.0% over the 2010s

Total healthcare inputs increased at an average annual rate of 3.8% between FYE 1996 and FYE 2018, resulting in healthcare inputs being 2.2 times greater in FYE 2018 than in FYE 1996.

Over this period, goods and services inputs contributed the largest share of input growth. This is in part because of two elements that are also included in output, and so have a minimal effect on productivity: non-NHS provision, which is included on this basis because of a lack of activity data, and GP-prescribed drugs, which are simultaneously considered both an input and an output. These series also recorded faster growth than other output elements over the period and more analysis on these is available in Section 4: Output.

Total inputs growth has varied over time and slowed markedly after FYE 2010, with an average growth of 5.4% over the 2000s and an average growth of 2.0% since FYE 2010, with lower growth in all three input components. The slower input growth is largely because of lower growth in real terms spending6 on healthcare. However, the years FYE 2015 and FYE 2016 stand out as having higher inputs growth than other years during the 2010s. This was because of a combination of factors, including growth in labour inputs, and stronger growth in goods and services inputs from non-NHS provided services, NHS providers’ intermediate consumption and agency staff.

Notes for: Inputs

Further analysis on the productivity of consultants is available from the Health Foundation.

General practice staff data used in these statistics are classified as Experimental Statistics and have in the past been subject to revisions.

In the NHS, bank staff work variable hours in response to demand, like agency staff. However, unlike agency staff, bank staff are NHS employees, providing services either through an in-house bank or an outsourced bank.

The chain-linking methodology used to construct the output and inputs indices means that the indices are constructed from a series of growth rates between consecutive pairs of years. As, a result, where new items are included, such as NHS bank staff in FYE 2016, these do not result in step-changes in the level of inputs or output. More information on chain-linking is available from this methodological note.

The two deflators applied to the largest shares of goods and services inputs expenditure are the intermediate consumption-specific version of the NHS Cost Inflation Index, which is used to deflate the intermediate consumption of NHS providers, and the NHS Cost Inflation Index for NHS Providers (produced by the Department of Health and Social Care), which is used to deflate the cost of non-NHS provided services.

Further information on NHS spending over time is available from Full Fact and the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

4. Output

Healthcare output is measured as the quantity of healthcare provided, adjusted for the quality of delivery. Quantity output is estimated using a cost-weighted activity index, where the growth rates of individual activity types are weighted by the share of expenditure that activity type accounts for. Because of this approach, growth in treatments that are common and expensive has a greater effect on overall output than a similar rate of growth in treatments that are uncommon or low cost.

Healthcare output is separately estimated for each of the following components:

Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) – includes hospital services, community care, mental health and ambulance services

Family Health Services (FHS) – includes general practice and publicly-funded dental treatment and sight tests

GP-prescribed drugs

non-NHS provision – includes healthcare funded by the government but provided by the private or third sector

A quality adjustment reflecting the extent to which the service succeeds in delivering its intended outcomes and the extent to which the service is responsive to users’ needs, is applied to the estimate of healthcare quantity output. More information on the methodology used to measure healthcare output can be found in Quality and Methodology Information and Sources and Methods Public Service Productivity Estimates: Healthcare (PDF, 328KB).

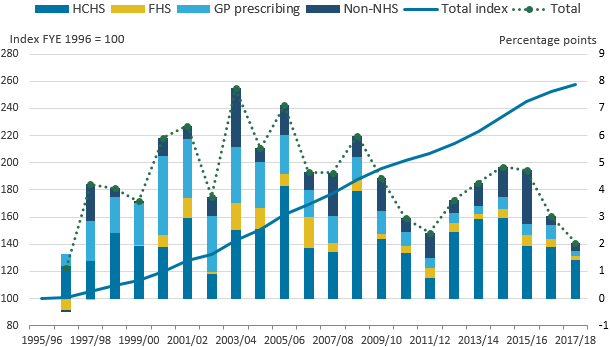

Growth in all four output components slowed in FYE 2018

All four components of output grew more slowly in financial year (April to March) ending (FYE) 2018 than in FYE 2017, with FYE 2018 being the first year since FYE 1997 when all four components experienced growth of less than 3% (Figure 2a).

Figure 2a: Public service healthcare quantity output growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1997 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- HCHS – Hospital and Community Health Services.

- FHS – Family Health Services.

Download this chart Figure 2a: Public service healthcare quantity output growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1997 to FYE 2018

Image .csv .xlsFigure 2b shows the effect of the four components of quantity output on total quantity output. As total quantity output is produced by weighting together the components by their share of total expenditure, the effect on output of each component depends both on its growth rate and share of expenditure.

Slower growth in total healthcare output was mainly driven by slower growth in HCHS, while GP-prescribing was also a substantial factor

Figure 2b: Public service healthcare contributions to quantity output growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- HCHS – Hospital and Community Health Services.

- FHS – Family Health Services.

- The sum of components of quantity output may not equal total output due to rounding.

Download this image Figure 2b: Public service healthcare contributions to quantity output growth by component, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (30.1 kB) .xls (39.9 kB)The largest contribution of the four output components to healthcare output growth comes from hospital and community health services (HCHS), the category that accounts for most of the healthcare expenditure1.

Growth in HCHS decreased from 3.0% in FYE 2017 to 2.2% in FYE 2018, below the 3.5% average of the entire series. This was because of slower output growth across a range of activity types, particularly outpatient consultations. The largest area of HCHS activity by expenditure, inpatient activity, grew at a similar rate in FYE 2016 and FYE 2017, but also slowed in FYE 2018.

Publicly-funded healthcare output from non-NHS providers grew by 2.4% in FYE 2018, the slowest growth in this component since FYE 2000. Growth in non-NHS providers’ spending was only slightly slower in FYE 2018 than FYE 2017, but much slower than the average for the series of 11.6%. Non-NHS provision has seen faster growth in earlier years in the series, although it should be noted that, earlier in the series, non-NHS provision accounted for a relatively small share of expenditure and so the very high growth rates seen in Figure 2a for non-NHS provision in FYE 1998 and FYE 2004 do not necessarily translate into exceptionally large absolute increases in healthcare output.

As many of the services provided by non-NHS providers, such as community health services and routine day case procedures, are also carried out by NHS providers, it may be that there is a correlation between faster growth in NHS-provided HCHS services and slower growth in non-NHS provided services. In this case, the relative growth rates of each component will partly depend on changes in the proportion of such treatment carried out by NHS and non-NHS providers. However, an absence of detailed data on the services provided by non-NHS providers limits the opportunity for further analysis of this component.

Family Health Services grew slightly more slowly in FYE 2018 but remained similar to the trend for recent years, while GP-prescribed drugs grew by 1.9% in FYE 2018, more slowly than the 5.8% growth in FYE 2017.

In FYE 2018, quantity output grew at its slowest rate since FYE 1997

Quantity output was over 2.6 times higher in FYE 2018 than FYE 1996.

Quantity output growth averaged 5.6% between FYE 2000 and FYE 2010 and 3.5% between FYE 2010 and FYE 2018. All four of the other components of quantity output saw slower growth in the 2010s than in the 2000s, although for the largest component, HCHS, there was a relatively smaller reduction, with an average annual growth rate of 4.1% during the 2000s and 3.2% between FYE 2010 and FYE 2018.

In FYE 2018, total quantity output grew by 2.0%, the slowest growth rate recorded since FYE 1997 and down from 3.0% in FYE 2017.

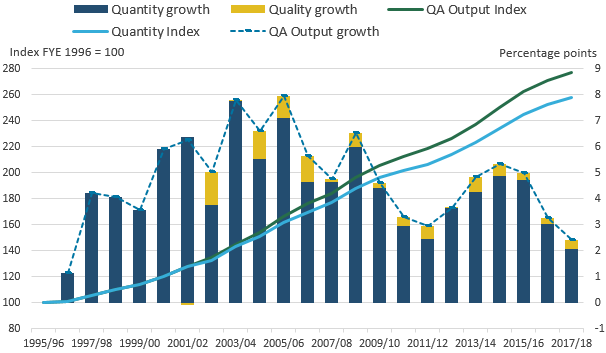

Figure 3 shows the effect on output of adjusting for changes in healthcare quality. The quality adjustment used incorporates a range of factors covering short-term post-operative survival rates, the estimated health gain from inpatient treatment, waiting times, patient satisfaction and primary care outcomes. The quality adjustment is applied to the output of Hospital and Community Health Services and Family Health Services, which together account for 79% of output.

More information about quality adjustment in public service productivity is available in this guide, while information about the quality adjustment used for healthcare output can be found in Quality adjustment of public service health output: current method (PDF, 152KB).

Adjusting for quality added 0.4 percentage points to output growth in FYE 2018, just below the average quality adjustment of 0.5 percentage points over the series

Figure 3: Public service healthcare quantity and quality adjusted output indices and growth rates, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- QA - quality adjusted.

- No quality adjustment is currently applied to non-NHS services.

Download this image Figure 3: Public service healthcare quantity and quality adjusted output indices and growth rates, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (33.0 kB) .xls (48.1 kB)In FYE 2018, the quality adjustment added 0.4 percentage points to the output growth rate, more than in FYE 2016 and FYE 2017, but just below the average for the series2. After adjusting for quality, output growth was still slower in FYE 2018 than in FYE 2017, at 2.4% and 3.2% respectively.

Notes for: Output

- HCHS output accounted for around 60% of expenditure across most of the time series.

- The quality adjustment for the UK edition of public service healthcare productivity may differ from that in the England edition despite both being calculated on data for England only. This is because of the “cubic splining” method used to convert financial year data into calendar years.

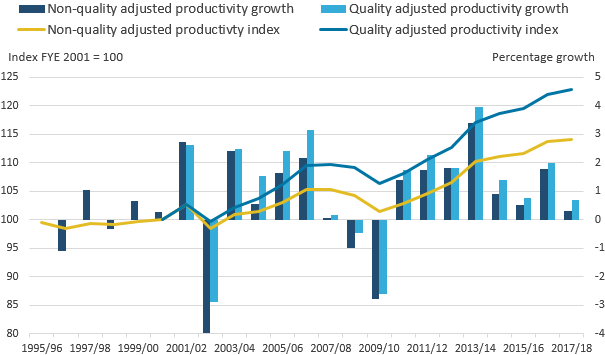

5. Productivity

Public service healthcare productivity is estimated by comparing output and input growth. If output growth exceeds input growth, productivity increases, meaning that more output is being produced for each unit of input. Conversely, if input growth exceeds output growth then productivity will fall.

In FYE 2018, productivity grew by 0.7% as output growth exceeded inputs growth

Figure 4 shows the growth of healthcare productivity with and without the quality adjustment applied, with both indices indexed to financial year (April to March) ending (FYE) 2001, the year before the quality adjustment was introduced.

Figure 4: Public service healthcare quantity and quality-adjusted productivity indices and growth rates, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 4: Public service healthcare quantity and quality-adjusted productivity indices and growth rates, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (25.4 kB) .xls (38.9 kB)As a result of slower output growth (2.0%) and slightly faster input growth (1.7%), non-quality adjusted productivity grew at only 0.3% in FYE 2018, down from 1.8% in FYE 2017. This meant non-quality adjusted productivity in FYE 2018 grew at its slowest rate since FYE 2010, the last time productivity fell.

Quality adjusted productivity increased by 0.7% in FYE 2018, faster than non-quality adjusted productivity, as a result of a positive quality adjustment, indicating improved service quality. This was also the slowest growth rate for quality adjusted productivity since FYE 2010, when inputs were growing at 7.4%, well above the average for the series, and output was growing at a similar rate to the series average.

Over the course of the time series from FYE 1996 to FYE 2018, non-quality adjusted productivity grew at an average rate of 0.6% and quality adjusted productivity at an average rate of 1.0%.

Quality adjusted healthcare productivity increased by 23.4% between FYE 1996 and FYE 2018, with most of this increase occurring since FYE 2010

Over the series, quality adjusted productivity increased by 23.4%, while non-quality adjusted productivity increased by 14.6%.

However, this increase was not continuous over the period and there are a few changes in the trend over the series:

between FYE 1996 and FYE 2003, the productivity level was largely unchanged, although it should be noted there was no quality adjustment effect until FYE 2002

between FYE 2003 and FYE 2007, productivity increased by an average annual rate of 2.4%, partly because of strong growth in quality

productivity growth nearly halted in FYE 2008 and fell in FYE 2010, a year of strong inputs growth, but slower HCHS output growth

Since FYE 2010, the average rate of input and output growth have both reduced, but output growth has not decreased as much as input growth, resulting in productivity growth in each of the last eight years of the series. While it accounts for just over one-third of the period covered by the series, the period from FYE 2010 onwards accounts for 71% of the total productivity growth since FYE 1996 for the quality adjusted measure and 87% of the growth in the non-quality adjusted measure.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Revisions

Several methodological improvements have been introduced in this publication, resulting in a substantial revision to the average growth rate of productivity relative to previous releases for the entire period from financial year (April to March) ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2017. There are also minor revisions from regular updates of the data used.

Healthcare output has been revised because of the introduction of an adjustment to account for the effect of year-to-year changes in the number of working days and total days on annual activity levels.

There have been substantial methodological changes to each of the three components of inputs:

labour inputs have been revised because of the inclusion of NHS bank staff

goods and services inputs have been revised because of changes to the deflators used, including the introduction of the NHS Cost Inflation Index

capital consumption inputs have been revised because of changes of the estimation of this component in the national accounts

More information on these changes can be found in Methodological developments to public service productivity: healthcare.

Figure 5 shows the revisions to labour inputs, which are mainly because of the introduction of NHS bank staff, which are measured using deflated expenditure data.

Figure 5: Growth rate for public service healthcare labour inputs for previous and current publication, England, financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 5: Growth rate for public service healthcare labour inputs for previous and current publication, England, financial year ending (FYE) 2015 to FYE 2018

Image .csv .xlsImprovements to the methodology for deflating goods and services inputs result in small changes throughout the series and slightly lower input growth overall

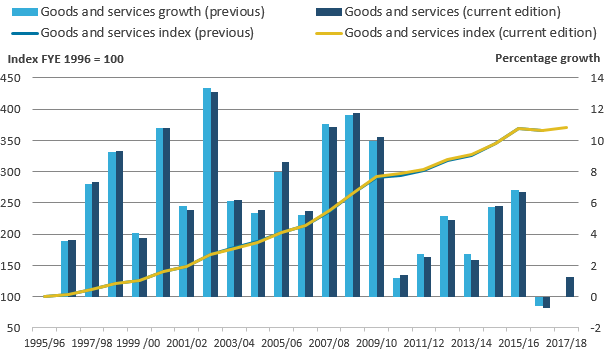

Figure 6 shows the effect of developments to the deflation methodology for goods and services inputs introduced in this article, which include:

the introduction of the new NHS Cost Inflation Index1 and a range of component parts of this index to deflate expenditure over the period FYE 2015 to FYE 2018

the removal of GP earnings from the pay cost deflator used for agency staff and non-NHS provided services between FYE 2004 and FYE 2015, to bring this period into line with the NHS Cost Inflation Index and earlier years

changes to the deflators used for general practice, dentistry, ophthalmology and pharmaceutical services to better reflect the input costs faced by providers of these services

Figure 6: Growth rate and index for public service healthcare goods and services inputs for current and previous publication, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 6: Growth rate and index for public service healthcare goods and services inputs for current and previous publication, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (29.9 kB) .xls (47.6 kB)Figure 6 shows the developments to the deflation methodology have caused small changes throughout the series, which result in just 0.1% less growth in goods and services inputs over the whole series from FYE 1996 to FYE 2017. However, the effect of these changes is not uniform over the whole series and over the period FYE 2006 to FYE 2013, the changes result in a higher level of goods and services inputs, with a maximum upward revision of 0.8% in FYE 2011.

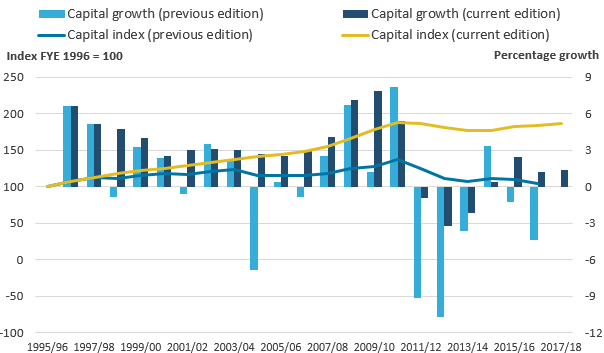

Figure 7 shows the substantial upward revision to capital consumption inputs following methodological improvements to the estimation of this element in the national accounts that were incorporated in Blue Book 2019. These improvements include a review of asset lives, which have been reduced in most cases, increasing capital consumption.

Figure 7: Growth rate and index for public service healthcare capital consumption inputs for current and previous publication, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 7: Growth rate and index for public service healthcare capital consumption inputs for current and previous publication, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (22.7 kB) .xls (50.7 kB)These improvements result in substantial changes to both the growth rate of capital consumption and its weight relative to the two other inputs components. The total increase in capital consumption between FYE 1996 and FYE 2017 has been revised up from 5.1% to 84.3%, and the previously substantial decline between FYE 2011 and FYE 2017 has been revised from a 23.6% fall to a 2.3% fall. The average weight of capital consumption in the overall inputs across the series has been revised up from 2.9% to 4.7%, with generally larger upward revisions in the 2010s than 2000s.

Figure 8: Cumulative contribution to revisions in public service healthcare inputs, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- The sum of the components of inputs revisions may not equal the total inputs revision due to rounding

Download this chart Figure 8: Cumulative contribution to revisions in public service healthcare inputs, England, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2017

Image .csv .xlsFigure 8 shows that the combined effect of the changes to inputs is to increase the level of inputs in FYE 2017 relative to FYE 1996 by 2.0%. Making up this change, 1.6 percentage points (pp) came from faster capital consumption growth and 0.6pp from labour revisions, mainly the effect of the introduction of bank staff on FYE 2017. Counteracting this was a negative 0.1pp downward revision effect from deflators’ changes to goods and services inputs.

There was also a 0.1pp reduction in total growth from changes to the relative weights of the three input components. This is partly because of the increase in the estimated cost of capital consumption, which increases the relative weight of this component. Because of further changes in the national accounts affecting the methodology for imputing Value Added Tax to government expenditure2, the increased weight of capital consumption results in a slightly greater downward effect on the weight of labour inputs than on goods and services inputs.

Year-on-year output growth rates have changed across the series following the introduction of the “days adjustment”, although the average annual rate is only slightly revised

Output has also been revised across the whole series because of the introduction of a “days adjustment” to account for the effect of year-to-year changes in the number of working days and total days on annual activity levels.

As healthcare output is calculated using a cost-weighted activity index, annual healthcare output may vary according to the number of days available to carry out activities during any year.

The total annual number of days varies with leap years, while the number of working days is also influenced by changes in bank holidays and position of weekends during the year.

The “days adjustment” reflects the fact that the total number of days and the number of working days affect the annual output of different parts of the healthcare service; with the total number of days having a greater effect on urgent care and the number of working days having a greater effect on scheduled treatments and consultations. The effect is particularly notable when using financial year (April to March) data, such as that which form the basis of our healthcare productivity measure, as some financial years may contain four Easter bank holidays and others none.

The “days adjustment” results in changes to the year-on-year growth rates across the series, but does not affect the long-run trend of output, in so far as the growth rate between any two years with the same number of working days and total days will be unchanged by the “days adjustment”.

However, total output growth across the series has been changed by developments to the deflators described in the revisions to goods and services inputs. These changes affect the non-NHS component of output, which is measured on an “output-equals-inputs” basis, resulting in a small decrease in overall output growth. However, it should be noted that because of the “output-equals-inputs” approach, these changes in non-NHS provided output will not affect productivity.

Figure 9: Growth rate and index for public healthcare non-quality adjusted output for current and previous publication, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 9: Growth rate and index for public healthcare non-quality adjusted output for current and previous publication, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

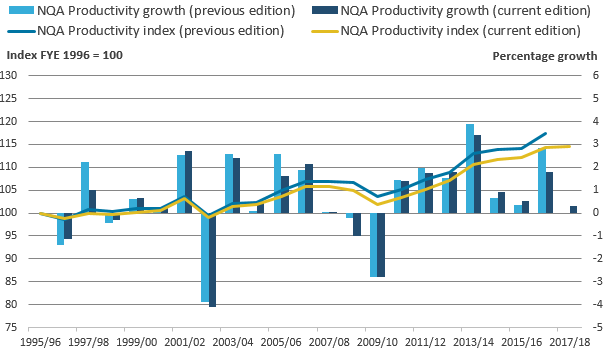

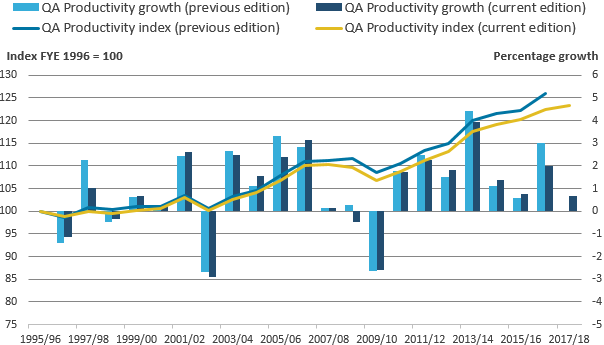

.PNG (32.1 kB) .xls (47.6 kB)Figures 10a and 10b show the revisions to non-quality adjusted and quality adjusted productivity, which are generally downwards in most years, and mainly as a result of upward revisions to inputs.

Figure 10a: Growth rate and index for public healthcare non-quality adjusted productivity for current and previous publication, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 10a: Growth rate and index for public healthcare non-quality adjusted productivity for current and previous publication, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (24.5 kB) .xls (47.6 kB)

Figure 10b: Growth rate and index for public healthcare quality adjusted productivity for current and previous publication, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 10b: Growth rate and index for public healthcare quality adjusted productivity for current and previous publication, financial year ending (FYE) 1996 to FYE 2018

.png (25.1 kB) .xls (48.1 kB)As described in Section 5: Productivity, overall productivity growth is greater in the quality adjusted measure than the non-quality adjusted measure. Over the whole series between FYE 1996 and FYE 2017, the changes introduced in this article result in the average annual growth rate of non-quality adjusted productivity being revised down from 0.8% to 0.6%, and quality adjusted productivity being revised down from 1.1% to 1.0%.

The difference in the size of the revision effect between quality adjusted and non-quality adjusted measures is largely because of rounding, rather than differences in the impact of methodological changes on quality adjusted and non-quality adjusted productivity.

However, as the non-quality adjusted measure records less productivity growth, the upward revision in inputs growth leaves the non-quality adjusted productivity index closer to zero, which is most noticeable for the earlier period where there is lower productivity growth. For instance, the total growth in non-quality adjusted productivity between FYE 1996 and FYE 2010 has nearly halved from 3.6% in the previous year's article to 1.9% in this article.

Notes for: Revisions

Figures for the NHS Cost Inflation Index are available from the Personal Social Services Research Unit’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2019.

Value Added Tax is not paid by public sector services but is imputed in the national accounts for consistency between government and private purchases.

7. Comparison of public service healthcare productivity estimates for England and the UK

These figures on an England and financial year basis were introduced in 2018, to provide a further measure to healthcare policy analysts, which is on a more consistent basis with other statistics that cover the English NHS, where financial data are typically reported on a financial year basis (that is, 1 April to 31 March)1. The methodological basis for these statistics is the same as for the UK publication and the data used are largely those used to produce the inputs and output for England in the UK measure.

The England financial year productivity measure differs from the UK calendar year productivity measure in the following ways:

quantity output is restricted to output from England only

the labour, and goods and services components of inputs are restricted to England only

many of the data sources used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) are created on a financial year basis, and a process called “cubic splining”2 is used to produce the calendar year measures; however, this process is not carried out in the production of this England, financial year measure

However, to maintain the methodological consistency with the UK productivity estimates, a number of data sources remain unchanged:

it is not possible to disaggregate the national accounts capital consumption data to a sub-UK level, so UK data continue to be used for this component

the three input components – labour, goods and services, and capital consumption – have been weighted together to form the total inputs index using UK-level data from the national accounts; this means that the proportion of total inputs made up of each of the three components is the same in both the UK and England series

in the UK healthcare productivity series, the quality adjustment to output is produced using England-only data, but is applied to UK output; while in the England financial year productivity series, the same quality adjustment is used, but is applied to England output only

Because of these changes, the England financial year healthcare productivity measure provides a better estimate for measuring the productivity of the English health system, while the UK calendar year productivity measure remains more suitable for measurement at a UK level3 and continues to be used as a component of total public service productivity.

It should, however, be noted that differences between the England and UK productivity measure cannot be used to estimate healthcare productivity for the devolved administrations. This is because, while data from the devolved administrations are used to produce the UK productivity series, there are differences in the coverage of the data, and some elements of devolved administration output and inputs are imputed based on data from England or the group of UK nations for which data are available.

Other healthcare output and productivity measures

The English financial year (April to March) productivity figure is produced on a similar basis to an alternative healthcare productivity measure produced by the Centre for Health Economics at the University of York in the series Productivity of the English NHS (PDF, 3.24MB). Both series apply the Atkinson Review (PDF, 1.08MB) framework, and the largest element of the quality adjustment is produced by the University of York and used in both publications. However, the two series provide slightly different estimates of productivity growth.

These differences arise from a number of differences in the source data used in the two publications including:

different sources and methods used in the calculation of output, including Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) output and the estimation of General Practitioner (GP) activity

different data sources used in the calculation of all three components of inputs

while the largest element of the quality adjustment is common between the two productivity measures, there are minor differences in some parts of the quality adjustment and their application to output data

Notes for: Comparison of public service healthcare productivity estimates for England and the UK

While the Centre for Health Economics at the University of York already produces a measure of healthcare productivity for England, there are a number of differences in the data sources and methods used, which are detailed in this section under “other healthcare output and productivity measures”.

“Cubic splining” involves the imputation of quarterly data based on trends in data over multiple financial years and constructs a calendar year figure based on these imputed quarterly figures.

In the calculation of the UK healthcare productivity statistics, the labour, goods and services, and output series for the constituent nations of the UK are weighted together using healthcare expenditure data from HM Treasury’s Country and regional analysis. Goods and services input growth for Northern Ireland is implicitly estimated to equal the rate of goods and services input growth for the rest of the UK.

8. Acknowledgements

The authors of this article are Narcisa Florea and James Lewis. The authors would like to thank Adriana Castelli, James Gaughan and Idaira Rodriguez Santana from the University of York for the provision of quality adjustment data and comments, and colleagues from the Department of Health and Social Care, and NHS England and NHS Improvement: Fiona Boyle, Alastair Brodlie, Cathy Costello, Zareen Khan, Robert Scott and Duncan Watson for the provision of output and input data and comments.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys