Cynnwys

- Main points

- Healthy life expectancy at birth and age 65 by upper tier local authority

- England

- English regions

- Upper tier local authorities

- Local authority comparison of 2012 to 2014 data with 2009 to 2011

- Interactive

- Healthy life expectancy at birth and age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation

- Main Comparisons

- National deciles of area deprivation comparison of 2012 to 2014 data with 2009 to 2011

- What are health expectancies?

- What are the measures of inequality?

- Methods

- Uses and users

- Feedback

- References

- Background notes

1. Main points

In 2012 to 2014, males at birth in England could expect to spend a higher proportion (79.7%) of their remaining lives in “Good” health, compared with females (76.9%).

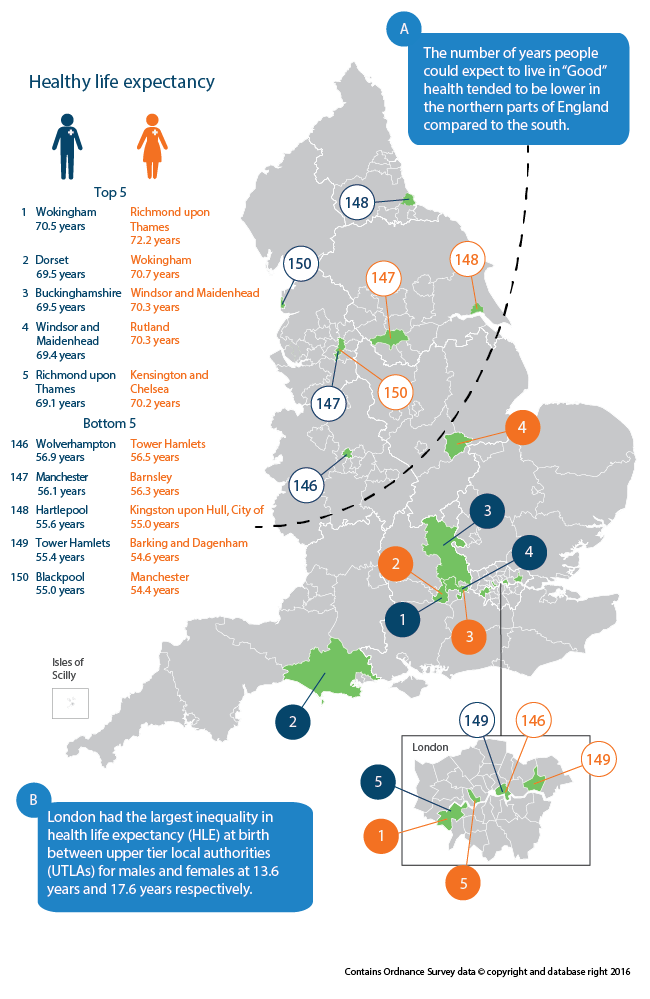

London had the largest inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) at birth between upper tier local authorities (UTLAs) for males and females at 13.6 years and 17.6 years respectively.

At birth, males in Wokingham could expect to live 15.5 years longer in “Good” health than males in Blackpool (70.5 years compared with 55.0 years).

At birth, females in Richmond upon Thames could expect to live 17.8 years longer in “Good” health than females in Manchester (72.2 years compared with 54.4 years).

There were 20 UTLAs for males and 25 UTLAs for females that had a significantly higher HLE than the current state pension age of 65.

For women at age 65, London had a significantly lower HLE than the England average at 10.9 years, despite having a higher life expectancy (LE) than any other part of the country.

Harrow had the largest significant improvements in HLE since 2009 to 2011, for males at birth and men at age 65 (5.7 years and 4.7 years respectively).

In the most deprived areas, males at birth could expect to live 19.0 years less of their lives in “Good” health compared with the least deprived areas as measured by the slope index of inequality (SII). For females, it was 20.2 years less.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. England

At birth

Males at birth in England could expect to spend a higher proportion (79.7%) of their remaining lives in “Good” health, compared with females (76.9%).

On the basis of mortality and health status rates in 2012 to 2014, a boy born in England could expect to live on average for 79.5 years, of which they could expect to spend 63.4 years in “Good” health. Whilst for a girl, life expectancy (LE) was 83.2 years, of which they could expect to spend 64.0 years in “Good” health.

Therefore, the gender gap between the number of years males and females could expect to spend in “Good” health was narrower at 0.6 years compared with LE at 3.7 years. Despite males expecting to live shorter lives on average compared with females, they could expect to spend a higher proportion of their remaining lives in “Good” health (79.7% compared with 76.9%).

When comparing the 2012 to 2014 data with the latest non-overlapping time period 2009 to 2011, the healthy life expectancy (HLE) estimate at birth for males increased by 0.2 years from 63.2 years to 63.4 years. Although HLE at birth increased for males, it did not keep pace with the increase in LE. Males born in 2012 to 2014 could expect to live a further 0.6 years than those born in 2009 to 2011. For females, HLE at birth declined by 0.1 years, from 64.2 years to 64.0 years whilst LE increased by 0.3 years.

This shows that there has been an expansion of morbidity (the number of years in “Not Good” health) for both males and females as there were larger increases in LE compared with HLE. This results in an increase in the number of years lived in “Not Good” health. Where there are larger increases in HLE compared with LE, this is referred to as compression of morbidity.

The higher increase in both LE and HLE at birth observed for males suggests that over time, the gender gap between males and females for LE and HLE has narrowed.

Age 65

Men and women at age 65 could expect to live over half of their remaining lives in “Good” health.

Between 2012 and 2014, men at age 65 could expect to live for a further 18.8 years with 10.6 of these years spent in “Good” health. On the other hand, women could expect to live a further 21.2 years of which 11.5 years could be spent in “Good” health. As a result, men and women at age 65 could expect to live over half of their remaining lives at age 65 in “Good” health (56.3% and 54.2% respectively).

Life expectancy (LE) and healthy life expectancy (HLE) for both men and women at age 65 increased between 2009 to 2011 and 2012 to 2014. Men at age 65 could expect to live an additional 0.4 years and an extra 0.2 years in “Good” health. Women at age 65 could expect to live an additional 0.1 years and 0.2 years in “Good” health. The increase in HLE for men at age 65 was the only statistically significant change since 2009 to 2011.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. English regions

At birth

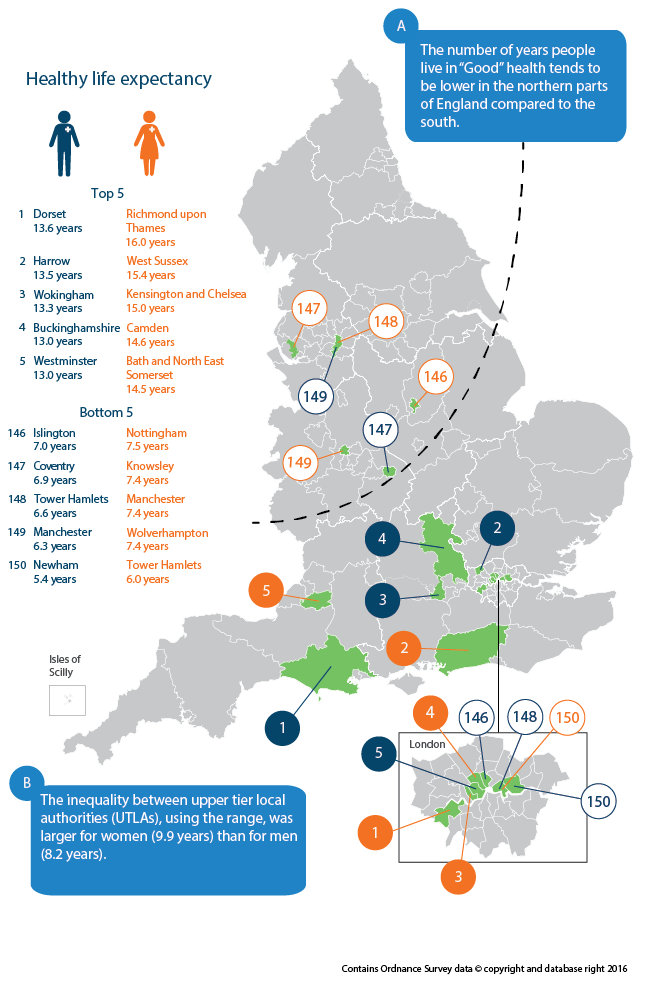

At birth, a north south divide was observed in healthy life expectancy (HLE), life expectancy (LE) and the proportion of life spent in “Good” health.

There was considerable variation in healthy life expectancy (HLE) at birth between different regions. Regional variations were patterned, with the South East, South West and East of England having a significantly higher HLE estimate at birth than England. For males and females, West Midlands, Yorkshire and The Humber, North West and North East all had a significantly lower HLE at birth than the England average. For males, the East Midlands also had an HLE estimate significantly lower compared with England.

For both males and females, HLE at birth was highest in the South East (65.9 years and 66.6 years respectively) and lowest in the North East (59.7 years and 59.8 years respectively). Therefore, the inequality in HLE at birth between regions was 6.2 years for males and 6.8 years for females.

Across all of the English regions, HLE at birth was highest among females compared with males. However, across all regions males spent a greater proportion of their remaining lives in “Good” health.

Table 1: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for males and females at birth by English regions, 2012 to 2014

| England | |||||||||||

| English region | LE (years) | HLE (years) | Lower 95% confidence interval | Upper 95% confidence interval | Proportion of life spent in "Good" health (%) | LE rank | HLE rank | ||||

| Males | |||||||||||

| South East | 80.5 | 65.9 | * | 65.5 | 66.3 | 81.8 | 1 | 1 | |||

| South West | 80.2 | 65.1 | * | 64.6 | 65.6 | 81.2 | 4 | 2 | |||

| East of England | 80.4 | 65.0 | * | 64.4 | 65.5 | 80.7 | 2 | 3 | |||

| London | 80.3 | 64.0 | 63.5 | 64.5 | 79.6 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| East Midlands | 79.4 | 62.7 | ** | 62.1 | 63.3 | 79.0 | 5 | 5 | |||

| West Midlands | 78.9 | 62.4 | ** | 61.9 | 62.9 | 79.2 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 78.7 | 61.4 | ** | 60.9 | 61.9 | 78.0 | 7 | 7 | |||

| North West | 78.1 | 61.1 | ** | 60.6 | 61.5 | 78.2 | 8 | 8 | |||

| North East | 78.0 | 59.7 | ** | 59.1 | 60.2 | 76.5 | 9 | 9 | |||

| England | 79.5 | 63.4 | 63.3 | 63.6 | 79.7 | ||||||

| Females | |||||||||||

| South East | 84.0 | 66.6 | * | 66.1 | 67.1 | 79.3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| East of England | 83.8 | 66.0 | * | 65.4 | 66.6 | 78.7 | 4 | 2 | |||

| South West | 83.9 | 65.6 | * | 65.0 | 66.1 | 78.1 | 3 | 3 | |||

| London | 84.2 | 64.1 | 63.6 | 64.7 | 76.2 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| East Midlands | 83.0 | 63.5 | 62.8 | 64.1 | 76.4 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| West Midlands | 82.9 | 62.5 | ** | 62.0 | 63.1 | 75.5 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 82.4 | 61.8 | ** | 61.2 | 62.4 | 75.0 | 7 | 7 | |||

| North West | 81.9 | 61.8 | ** | 61.3 | 62.2 | 75.5 | 8 | 8 | |||

| North East | 81.7 | 59.8 | ** | 59.2 | 60.4 | 73.2 | 9 | 9 | |||

| England | 83.2 | 64.0 | 63.8 | 64.2 | 76.9 | ||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||||||||

| Notes: | |||||||||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | |||||||||||

| 2. Regions are presented by gender and have been ranked at the England level, based on HLE to more than one decimal place. Their respective rankings within England are also shown. | |||||||||||

| 3. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | |||||||||||

| 4. * denotes that the region HLE estimate is significantly higher than the England HLE estimate at the 95% confidence level. | |||||||||||

| 5. ** denotes that the region HLE estimate is significantly lower than the England HLE estimate at the 95% confidence level. | |||||||||||

| 6. The significance test refers to a one tailed Z test of the difference of the estimates as detailed in Jagger et al., (2007) | |||||||||||

Download this table Table 1: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for males and females at birth by English regions, 2012 to 2014

.xls (33.8 kB)When comparing 2012 to 2014 with 2009 to 2011 across all regions, life expectancy (LE) increased at a faster rate for males and females compared with HLE at birth. One exception was males in London where there was a 1.0 year increase in both LE and HLE at birth. The increase in HLE at birth for males in London was the only significant improvement over the time period across the regions. The majority of regions for males showed an increase in HLE at birth, with the exception of East Midlands, West Midlands and North East where there was a decline in HLE at birth since 2009 to 2011.

For females, the majority of regions showed a decline in HLE at birth with the exception of London, East Midlands and North West where there was an increase in HLE at birth since 2009 to 2011. However, none of these differences were significant.

When looking at HLE at birth in terms of the State Pension age, using 65 for both males and females, at which it will be by 2018, when assessed with 95% confidence intervals, only the South East for males had a significantly higher HLE estimate than the State Pension age. For females, the South East, South West and East of England had a HLE estimate significantly higher than the State Pension age.

At age 65

For women at age 65, London had a significantly lower healthy life expectancy (HLE) than the England average at 10.9 years, despite having a higher life expectancy (LE) than any other part of the country.

The regional pattern observed at birth is also present at age 65. For men and women, healthy life expectancy (HLE) at age 65 was highest in the South East (11.8 years and 13.3 years respectively) and lowest in the North East (8.8 years and 9.4 years respectively).

Similar to at birth, although men had a shorter HLE at age 65 across all regions, they could expect to spend a higher proportion of their remaining lives in “Good” health. However, one exception was the South East where women could expect to spend a higher proportion of their remaining lives in “Good” health (61.3% compared with 61.0% for men).

Interestingly, for women at age 65, London had a significantly lower HLE than the England average at 10.9 years, despite having a higher LE than any other part of the country

The majority of regions for men showed an increase in HLE at age 65, with the exception of East Midlands, West Midlands and East of England where there was a decline in HLE at birth since 2009 to 2011.

For women, unlike at birth, most regions showed an increase in HLE at age 65 with the exception of South West, West Midlands and East of England where there was a decline in HLE at age 65 since 2009 to 2011.

Table 2: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for men and women at age 65 by English regions, 2012 to 2014

| England | ||||||||

| English region | LE (years) | HLE (years) | Lower 95% confidence interval | Upper 95% confidence interval | Proportion of life spent in "Good" health (%) | LE rank | HLE rank | |

| Men | ||||||||

| South East | 19.3 | 11.8 | * | 11.4 | 12.2 | 61.0 | 2 | 1 |

| South West | 19.3 | 11.6 | * | 11.2 | 12.0 | 60.1 | 3 | 2 |

| East of England | 19.3 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 11.4 | 56.8 | 1 | 3 | |

| London | 19.2 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 11.0 | 55.0 | 4 | 4 | |

| East Midlands | 18.6 | 10.0 | ** | 9.5 | 10.5 | 53.9 | 5 | 5 |

| West Midlands | 18.5 | 10.0 | ** | 9.6 | 10.4 | 54.2 | 6 | 6 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 18.2 | 10.0 | ** | 9.6 | 10.3 | 54.7 | 7 | 7 |

| North West | 18.0 | 9.7 | ** | 9.4 | 10.1 | 54.2 | 8 | 8 |

| North East | 17.9 | 8.8 | ** | 8.4 | 9.3 | 49.4 | 9 | 9 |

| England | 18.8 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 56.3 | |||

| Women | ||||||||

| South East | 21.7 | 13.3 | * | 12.9 | 13.7 | 61.3 | 3 | 1 |

| South West | 21.8 | 12.6 | * | 12.2 | 13.0 | 57.9 | 2 | 2 |

| East of England | 21.6 | 12.0 | * | 11.6 | 12.5 | 55.7 | 4 | 3 |

| East Midlands | 21.1 | 11.3 | 10.8 | 11.9 | 53.8 | 6 | 4 | |

| London | 21.9 | 10.9 | ** | 10.5 | 11.4 | 49.8 | 1 | 5 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 20.6 | 10.5 | ** | 10.1 | 11.0 | 51.3 | 7 | 6 |

| West Midlands | 21.1 | 10.5 | ** | 10.1 | 10.9 | 49.9 | 5 | 7 |

| North West | 20.3 | 10.4 | ** | 10.1 | 10.8 | 51.4 | 8 | 8 |

| North East | 20.0 | 9.4 | ** | 8.9 | 9.9 | 46.9 | 9 | 9 |

| England | 21.2 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 11.6 | 54.2 | |||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | ||||||||

| 2. Regions are presented by gender and have been ranked at the England level, based on HLE to more than one decimal place. Their respective rankings within England are also shown. | ||||||||

| 3. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | ||||||||

| 4. * denotes that the region HLE estimate is significantly higher than the England HLE estimate at the 95% confidence level. | ||||||||

| 5. ** denotes that the region HLE estimate is significantly lower than the England HLE estimate at the 95% confidence level. | ||||||||

| 6. The significance test refers to a one tailed Z test of the difference of the estimates as detailed in: Jagger et al., (2007) | ||||||||

Download this table Table 2: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for men and women at age 65 by English regions, 2012 to 2014

.xls (33.3 kB)When 2012 to 2014 is compared with 2009 to 2011, there were 3 regions (South East, London and Yorkshire and The Humber) where the increase in HLE at age 65 exceeded that of LE for men aged 65. As found at birth, the increase in HLE at age 65 for men in London was the only significant improvement over the time period across the regions at 0.7 years.

For women, South East, London, Yorkshire and The Humber, North West and North East were the regions where the increase in HLE at age 65 exceeded that of LE. However, none of these increases in HLE for women at age 65 were significant over the non-overlapping time period.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Interactive

Explore healthy life expectancy (HLE) for your area using our animated map.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Healthy life expectancy at birth and age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation

In the second part of this publication, the following analysis allows us to assess the scale of inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) by national deciles of deprivation produced by clustering lower super output areas (LSOAs) by the English Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010 (IMD 2010). This will add context to the HLE estimates by UTLA and will further allow health organisations to make informed decisions regarding the allocation of funding and resources. The range and slope index of inequality (SII) are the 2 measures of inequality that are provided for the period 2012 to 2014 as well as significance testing to calculate the change over a non-overlapping time period 2009 to 2011.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. Main Comparisons

At birth

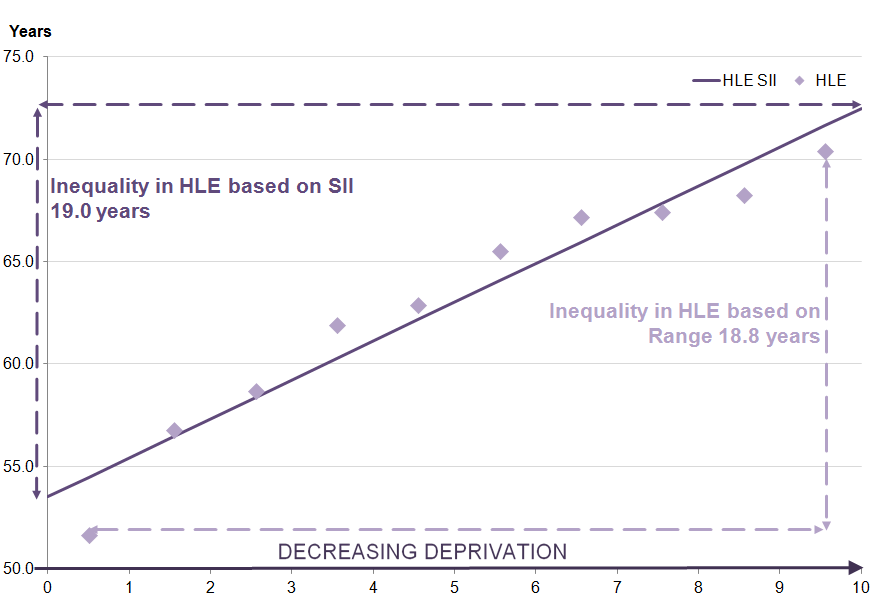

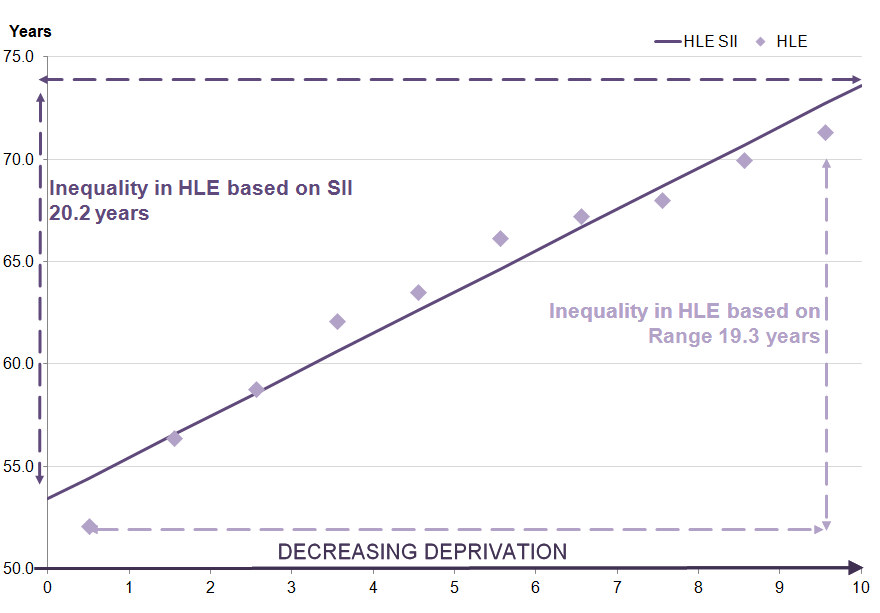

In the most deprived areas, males at birth could expect to live 19.0 years less of their lives in “Good” health compared with the least deprived areas as measured by the slope index of inequality (SII). For females, it was 20.2 years less.

In the most deprived 10% of lower super output areas (LSOAs) (decile 1) in England, healthy life expectancy (HLE) at birth was 18.8 years lower for males and 19.3 years lower for females, compared with the least deprived 10% of LSOAs (decile 10). This is measured by the range which is the absolute difference between the most and least deprived deciles. This inequality is almost twice as wide as the difference seen in life expectancy (LE) at birth which was 9.1 years for males, whereas for females, it was almost 3 times wider at 6.9 years.

The slope index of inequality (SII) can be interpreted in the same way as the range but takes into account inequality across the whole distribution as well as giving greater weight to larger populations and less weight to smaller populations. Using the SII shows a slightly greater inequality than the range between the most and least deprived areas at 19.0 years for males and 20.2 years for females. When assessing LE with the same measure, this was less than half the size at 9.2 years for males and less than a third of the size for females at 7.0 years. This demonstrates that greater inequality exists in the prevalence of self-assessed “Good” general health than mortality.

Table 5: Slope index of inequality (SII) and range for healthy life expectancy (HLE), life expectancy (LE) and proportion of life spent in "Good" health for males and females at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

| England | ||||||||||

| Range (years) | SII (years) | Lower 95% confidence interval | Upper 95% confidence interval | |||||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| LE | 9.1 | 9.2 | 7.7 | 10.7 | ||||||

| HLE | 18.8 | 19.0 | 15.1 | 22.8 | ||||||

| Proportion of life in "Good" health (%) | 14.9 | 15.0 | 11.1 | 18.8 | ||||||

| Females | ||||||||||

| LE | 6.9 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 8.0 | ||||||

| HLE | 19.3 | 20.2 | 16.8 | 23.5 | ||||||

| Proportion of life in "Good" health (%) | 17.1 | 18.0 | 14.5 | 21.6 | ||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | ||||||||||

| 2. Estimates are presented by gender. | ||||||||||

| 3. Range is calculated by taking the difference between decile 1 and decile 10. | ||||||||||

| 4. SII is calculated by taking the difference between the extremes of a population weighted regression line of best fit. | ||||||||||

Download this table Table 5: Slope index of inequality (SII) and range for healthy life expectancy (HLE), life expectancy (LE) and proportion of life spent in "Good" health for males and females at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

.xls (28.7 kB)

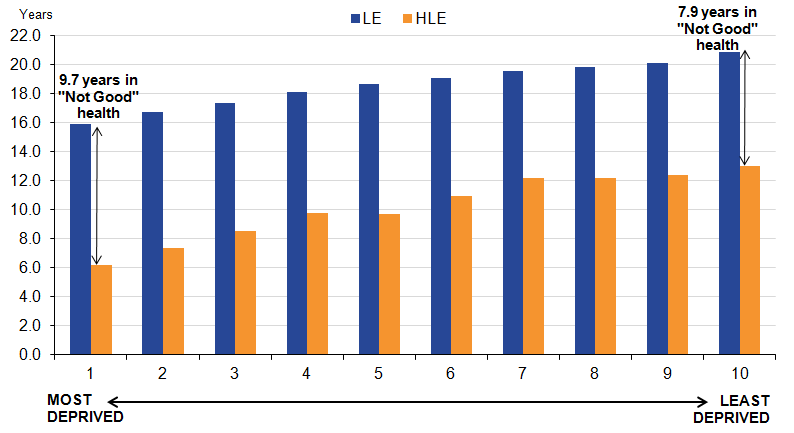

Figure 1: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for males at birth by deprivation decile in England

2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Download this image Figure 1: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for males at birth by deprivation decile in England

.png (27.1 kB) .xls (70.1 kB)

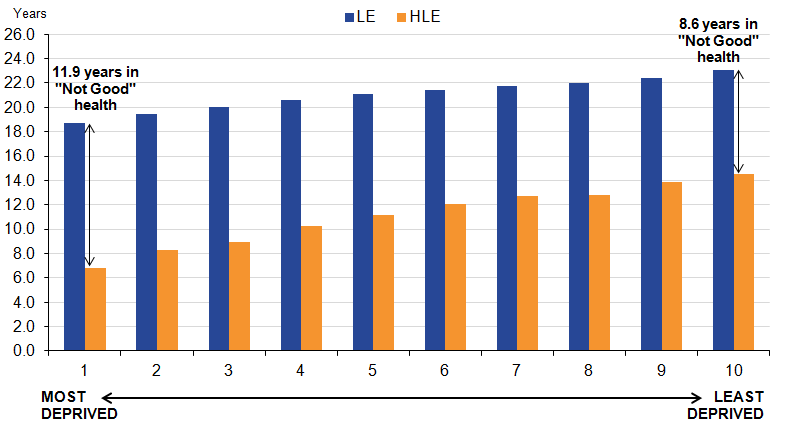

Figure 2: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for females at birth by deprivation decile in England

2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Download this image Figure 2: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for females at birth by deprivation decile in England

.png (25.6 kB) .xls (55.3 kB)It has been found at the national level that females live longer than males and can expect to live more of their remaining life in “Good” health. This is also the case within each decile with the exception of HLE for decile 2. Within each decile, the gender differences in HLE are narrower compared with LE, therefore most of the extra years of life expected by females are not spent in “Good” health.

The gender disadvantage of males in regards to LE could be overcome by socio-economic advantage. Those males living in the least deprived 6 deciles (5 through to 10) have longer LE than females in decile 1. A similar pattern was observed for HLE at birth, although in this instance, males in deciles 2 through to 10 have a longer HLE at birth than females in the most deprived decile (decile 1).

Table 6: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for males and females at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

| England | ||||||||||||||

| LE (years) | HLE (years) | Lower 95% confidence interval | Upper 95% confidence interval | Proportion of life in "Good" health (%) | ||||||||||

| Males | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 74.1 | 51.7 | 51.2 | 52.2 | 69.7 | |||||||||

| 2 | 76.3 | 56.8 | 56.3 | 57.4 | 74.5 | |||||||||

| 3 | 77.4 | 58.7 | 58.2 | 59.3 | 75.9 | |||||||||

| 4 | 78.7 | 62.0 | 61.4 | 62.5 | 78.7 | |||||||||

| 5 | 79.7 | 62.9 | 62.4 | 63.5 | 79.0 | |||||||||

| 6 | 80.3 | 65.6 | 65.1 | 66.1 | 81.6 | |||||||||

| 7 | 81.1 | 67.2 | 66.7 | 67.7 | 82.9 | |||||||||

| 8 | 81.5 | 67.5 | 66.9 | 68.0 | 82.7 | |||||||||

| 9 | 82.1 | 68.3 | 67.8 | 68.9 | 83.2 | |||||||||

| 10 | 83.2 | 70.4 | 69.9 | 71.0 | 84.6 | |||||||||

| Females | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 79.1 | 52.1 | 51.5 | 52.7 | 65.9 | |||||||||

| 2 | 80.7 | 56.4 | 55.8 | 57.0 | 69.9 | |||||||||

| 3 | 81.6 | 58.8 | 58.2 | 59.4 | 72.1 | |||||||||

| 4 | 82.4 | 62.1 | 61.5 | 62.7 | 75.4 | |||||||||

| 5 | 83.2 | 63.6 | 62.9 | 64.2 | 76.4 | |||||||||

| 6 | 83.7 | 66.2 | 65.6 | 66.8 | 79.1 | |||||||||

| 7 | 84.3 | 67.2 | 66.7 | 67.8 | 79.8 | |||||||||

| 8 | 84.6 | 68.1 | 67.5 | 68.6 | 80.4 | |||||||||

| 9 | 85.2 | 70.0 | 69.4 | 70.6 | 82.2 | |||||||||

| 10 | 86.1 | 71.4 | 70.8 | 72.0 | 82.9 | |||||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Deciles are presented by gender. | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | ||||||||||||||

Download this table Table 6: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for males and females at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

.xls (30.2 kB)The proportion of life spent in “Good” health allows us to see whether those who have a shorter LE could still expect to live the same proportion of their remaining life in “Good” general health. However, the figures show that this isn’t the case. For males, even though those in the most deprived decile (decile 1) have the shortest LE, they can also expect to spend a smaller proportion of their remaining life in “Good” health when compared with those in the least deprived decile (decile 10) with the longest LE. This difference amounts to those in the least deprived decile (decile 10) having an extra 14.9 percentage points of their longer life in “Good” general health compared with those in the most deprived decile (decile 1). Females in the least deprived decile (decile 10) can expect an extra 17.1 percentage points of their life in “Good” health when compared with females in the most deprived decile (decile 1). Females in the most deprived decile (decile 1) could expect to spend less than two-thirds of their LE in good general health.

When analysing the difference using the SII, males in the least deprived areas could expect to live an extra 15.0 percentage points of their life in “Good” health compared with males in the most deprived areas; for females the inequality was 18.0 percentage points (see Table 5).

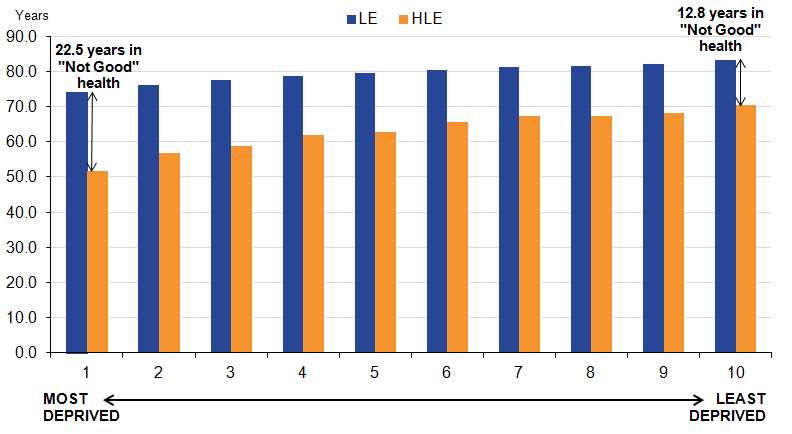

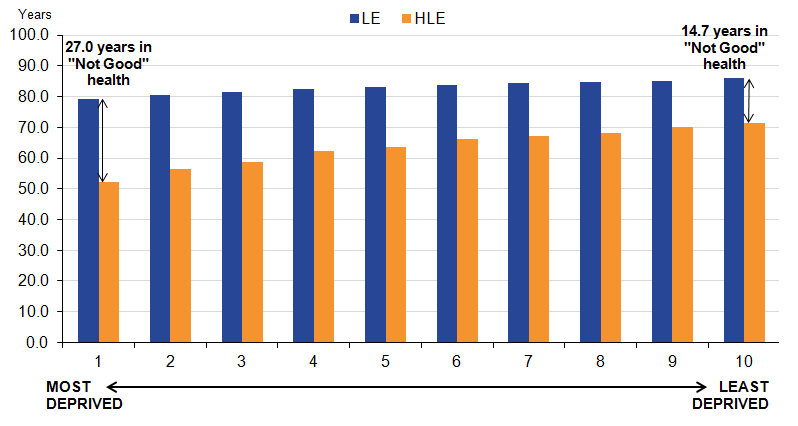

The pattern of inequality in HLE at birth, whereby the estimate falls in line with the increasing deprivation, can also be illustrated through looking at years spent in “Not Good” health. Males in the least deprived decile (decile 10) could expect to spend 12.8 years in “Not Good” health compared with 22.5 years in the most deprived decile (decile 1). For females these figures are 14.7 years in “Not Good” health in the least deprived decile (decile 10) and 27.0 years in the most deprived decile (decile 1, see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for males at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Download this image Figure 3: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for males at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

.png (28.8 kB) .xls (59.9 kB)

Figure 4: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for females at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Download this image Figure 4: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for females at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

.png (27.4 kB) .xls (58.4 kB)At age 65

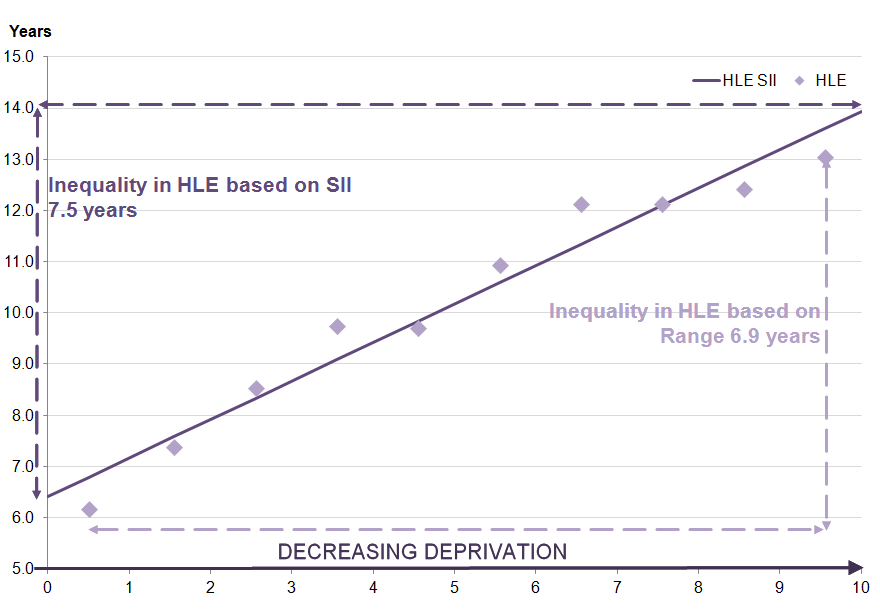

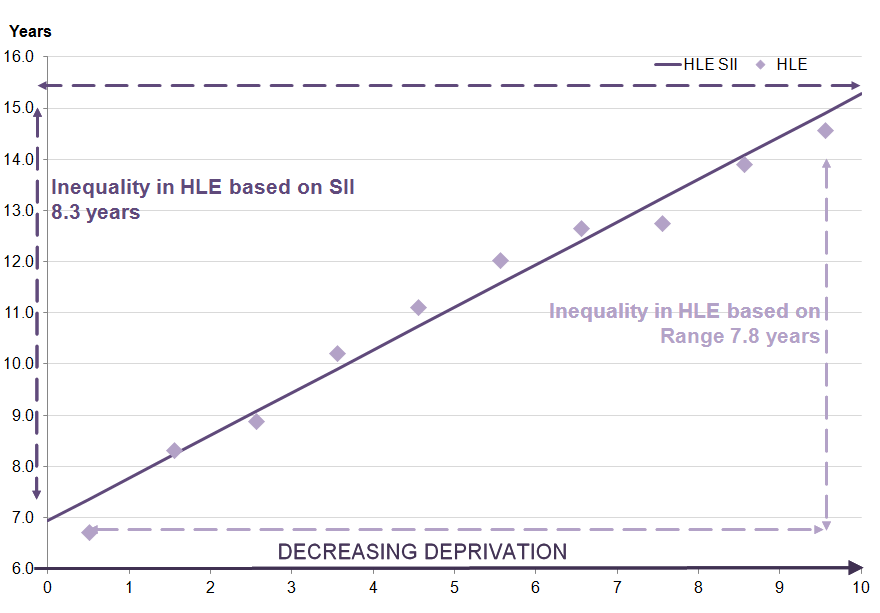

Men at age 65 in the least deprived areas could expect to live 7.5 years longer in “Good” health than those in the most deprived areas as measured by the slope index of inequality (SII). For women, this was 8.3 years longer.

At age 65, healthy life expectancy (HLE) in the most deprived 10% of lower super output areas (LSOAs) in England (decile 1) was 6.9 years lower for men and 7.8 years lower for women than the least deprived 10% of LSOAs (decile 10) when measured by the range. The inequality is somewhat wider than in life expectancy (LE) where the difference was 5.1 years for men and 4.5 years for women.

The slope index of inequality (SII) in HLE at age 65 shows greater inequality than the range at 7.5 years for men and 8.3 years for women between the most and least deprived areas. When assessing LE with the same measure, the SII is lower at 5.2 years for men and 4.5 years for women.

Table 7: Slope index of inequality (SII) and range for healthy life expectancy (HLE), life expectancy (LE) and proportion of life spent in "Good" health for men and women at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

| England | ||||

| Range (years) | SII (years) | Lower 95% confidence interval | Upper 95% confidence interval | |

| Men | ||||

| LE | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 5.8 |

| HLE | 6.9 | 7.5 | 6.2 | 8.8 |

| Proportion of life in "Good" health (%) | 23.4 | 26.0 | 18.9 | 33.1 |

| Women | ||||

| LE | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.1 |

| HLE | 7.8 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 9.4 |

| Proportion of life in "Good" health (%) | 26.8 | 28.8 | 23.7 | 33.9 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | ||||

| 2. Estimates are presented by gender. | ||||

| 3. Range is calculated by taking the difference between decile 1 and decile 10. | ||||

| 4. SII is calculated by taking the difference between the extremes of a population weighted regression line of best fit. | ||||

Download this table Table 7: Slope index of inequality (SII) and range for healthy life expectancy (HLE), life expectancy (LE) and proportion of life spent in "Good" health for men and women at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

.xls (28.7 kB)

Figure 5: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for men at age 65 by deprivation decile

England, 2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Download this image Figure 5: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for men at age 65 by deprivation decile

.png (28.2 kB) .xls (58.4 kB)

Figure 6: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for women at age 65 by deprivation decile

England, 2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Download this image Figure 6: Inequality in healthy life expectancy (HLE) for women at age 65 by deprivation decile

.png (28.1 kB) .xls (57.9 kB)HLE at age 65 generally increased between each decile from most to least deprived but for men, deciles 4 and 5 and deciles 7 and 8 had the same HLE at 9.7 years and 12.1 years respectively. This has resulted in decile 5 for men having a slighter smaller proportion of remaining life in “Good” health compared with decile 4. Similarly, decile 8 had a smaller proportion of remaining life in “Good” health compared with decile 7, instead of the proportion steadily increasing in line with lowering exposure to deprivation. Decile 7 also had a larger proportion of remaining life in “Good” health compared with decile 9. For women, decile 7 also had a larger proportion of remaining life in “Good” health compared with decile 8, which could be explained by the small differences in LE and HLE at age 65 between these 2 neighbouring deciles.

Table 8: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for men and women at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

| England | |||||

| LE (years) | HLE (years) | Lower 95% confidence interval | Upper 95% confidence interval | Proportion of life in "Good" health (%) | |

| Men | |||||

| 1 | 15.8 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 39.0 |

| 2 | 16.8 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 43.9 |

| 3 | 17.3 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 49.2 |

| 4 | 18.1 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 53.8 |

| 5 | 18.7 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 10.1 | 52.0 |

| 6 | 19.0 | 10.9 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 57.4 |

| 7 | 19.5 | 12.1 | 11.7 | 12.5 | 62.2 |

| 8 | 19.8 | 12.1 | 11.7 | 12.6 | 61.3 |

| 9 | 20.1 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 61.7 |

| 10 | 20.9 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 13.5 | 62.4 |

| Women | |||||

| 1 | 18.6 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 36.2 |

| 2 | 19.5 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 42.6 |

| 3 | 20.0 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 9.4 | 44.5 |

| 4 | 20.6 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 49.7 |

| 5 | 21.1 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 52.7 |

| 6 | 21.4 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 12.5 | 56.3 |

| 7 | 21.8 | 12.7 | 12.2 | 13.1 | 58.3 |

| 8 | 22.0 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 13.2 | 58.0 |

| 9 | 22.4 | 13.9 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 62.0 |

| 10 | 23.2 | 14.6 | 14.1 | 15.1 | 63.0 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | |||||

| 2. Deciles are presented by gender. | |||||

| 3. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | |||||

Download this table Table 8: Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for men and women at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, 2012 to 2014

.xls (29.2 kB)The proportion of life men and women could expect to spend in “Good” health at age 65 by deciles of deprivation are shown in Table 8. The gap between the most deprived and least deprived deciles for men was 23.4 percentage points and 26.8 percentage points for women. This means that for the most deprived areas, men and women could expect to live 39.0% and 36.2% of their remaining lives in “Good” health, whilst men and women in the least deprived areas could expect to live a larger proportion of their remaining lives in “Good” health at 62.4% and 63.0% respectively.

The pattern of inequality in HLE at age 65, whereby the estimate falls in line with the increasing deprivation, can also be illustrated through looking at remaining years spent in “Not Good” health. Men in the least deprived decile (decile 10) could expect to spend 7.9 years in “Not Good” health compared with 9.7 years in the most deprived decile (decile 1). For women, these figures are 8.6 years in “Not Good” health in the least deprived decile (decile 10) and 11.9 years in the most deprived decile (decile 1, see Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7. Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for men at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Download this image Figure 7. Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for men at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

.png (27.6 kB) .xls (58.4 kB)

Figure 8. Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for women at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address.

Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Download this image Figure 8. Healthy life expectancy (HLE) and life expectancy (LE) for women at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, England 2012 to 2014

.png (26.7 kB) .xls (57.9 kB)10. National deciles of area deprivation comparison of 2012 to 2014 data with 2009 to 2011

To be confident about the conclusions drawn about changes in healthy life expectancy (HLE) estimates over time, statistical significance tests are performed. Please see methods section for more detail.

At birth

To find out whether or not there has been a significant change in the level of inequality and health improvement across the deciles over time, 2 non-overlapping time points were compared. This is the first time it has been possible to compare changes over time as the 2009 to 2011 publication was the first in this series.

For males between 2009 to 2011 and 2012 to 2014, the range in healthy life expectancy (HLE) between the least and most deprived deciles increased by 0.4 years and the slope index of inequality (SII) declined by 0.4 years. For females, the HLE range and SII increased by 0.3 years and 0.1 years respectively. However, none of these changes were significant.

Decile 2 was the only decile to have a significant increase in HLE at birth which was observed for males with an increase of 1.0 year from 55.8 years in 2009 to 2011 to 56.8 years in 2012 to 2014. There were no other significant changes.

Table 9: Significant changes to healthy life expectancy (HLE) estimates for males at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, England, between 2009 to 2011 and 2012 to 2014

| Decile | HLE 2009 to 2011 | HLE 2012 to 2014 | Change | |

| 2 | 55.8 | 56.8 | 1.0 | * |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | ||||

| 2. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | ||||

| 3. * indicates a significant increase to HLE over the time period. | ||||

| 4. The significance test refers to a one tailed Z test of the difference of the estimates as detailed in Jagger et al., (2007) | ||||

Download this table Table 9: Significant changes to healthy life expectancy (HLE) estimates for males at birth by national deciles of area deprivation, England, between 2009 to 2011 and 2012 to 2014

.xls (27.1 kB)At age 65

For men between 2009 to 2011 and 2012 to 2014, the range in healthy life expectancy (HLE) between the least and most deprived deciles and the slope index of inequality (SII) both declined by 0.3 years. For women, the HLE range increased by 0.2 years whereas the SII increased by 0.1 years. However, none of these changes were significant.

Decile 4 was the only decile to have a significant increase in HLE at age 65 which was for men with an increase of 0.9 years, from 8.9 years in 2009 to 2011 to 9.7 years in 2012 to 2014. There were no other significant changes.

Table 10: Significant changes to healthy life expectancy (HLE) estimates for men at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, England, between 2009 to 2011 and 2012 to 2014

| Decile | HLE 2009 to 2011 | HLE 2012 to 2014 | Change | |

| 4 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 0.9 | * |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Excludes residents of communal establishments except NHS housing and students in halls of residence where inclusion takes place at their parents' address. | ||||

| 2. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | ||||

| 3. * indicates a significant increase to HLE over the time period. | ||||

| 4. The significance test refers to a one tailed Z test of the difference of the estimates as detailed in: Jagger et al., (2007) | ||||

Download this table Table 10: Significant changes to healthy life expectancy (HLE) estimates for men at age 65 by national deciles of area deprivation, England, between 2009 to 2011 and 2012 to 2014

.xls (27.1 kB)11. What are health expectancies?

Health expectancies add a quality of life dimension to estimates of life expectancy (LE) by dividing expected lifespan into time spent in different states of health. We routinely publish 2 types of health expectancies. The first is healthy life expectancy (HLE), which estimates lifetime spent in “Very good” or “Good” health based on how individuals perceive their general health. The second is disability-free life expectancy (DFLE), which estimates lifetime free from a limiting persistent illness or disability. This is based upon a self-rated assessment of how health limits an individual’s ability to carry out day-to-day activities. Both health expectancies are summary measures of population health and important indicators of the well-being of society, providing context to the impacts of policy changes and interventions at both national and local levels. Health expectancies are used across public, private and voluntary sectors, in the assessment of healthy ageing, fitness for work, monitoring health improvement, extensions to the state pension age, pension provision and health and social care need.

The importance of HLE as a summary measure of population health is reflected in its inclusion in the 2 high level outcomes for the Public Health Outcomes Framework (PHOF). The first outcome is increased HLE, taking account of the quality as well as the length of life. The second is to reduce differences in LE and HLE between communities, through greater improvements in more disadvantaged communities. The vision for the outcomes is “to improve and protect the nation’s health and wellbeing, and improve the health of the poorest fastest” (page 9, DH, 2012) .

The 2012 to 2014 HLE figures in this publication represent the expected life years in “Good” health for an individual, assuming 2012 to 2014 mortality and health status rates apply throughout that individual’s life. Therefore, they provide a snapshot of the health status of the population(s) in England during 2012 to 2014. The health status and mortality rates of a population change year on year due to exposure to different risks and treatments affecting health, and also through inward and outward migration. Therefore, the estimates reported in this bulletin should not be interpreted as the actual number of years a person will live in “Good” health. HLE figures are a likely estimate should the health status and mortality rates remain fairly stable over the life course.

HLE estimates are, in part, subjective and based upon the following survey question:

“How is your health in general; would you say it was...”

- Very good

- Good

- Fair

- Bad

- Very bad

If a respondent answered “Very good” or “Good” they were classified as having “Good” health. Those who answered “Fair”, “Bad”, or “Very bad” were classified as having “Not Good” health.

Changes in health expectancies over time are assessed by comparing non-overlapping time periods. Therefore, estimates for 2012 to 2014 should not be compared with estimates for 2011 to 2013 or 2010 to 2012 for example, as they will contain some of the same survey respondents.

For the first time, a non-overlapping period is available and the HLE estimates are compared with 2009 to 2011 estimates in order to assess how HLE has changed for England, regions, UTLAs and by national deciles of area deprivation.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys12. What are the measures of inequality?

There are 2 measures that have been used to compare the least and most deprived groups of areas. The first is the range, which shows the absolute difference between the least and most deprived deciles. The second is the slope index of inequality (SII), which measures the gap in healthy life expectancy (HLE) by taking into account the inequality across all adjacent deciles of relative deprivation, rather than focusing only on the extremes.

The use of the range can mask the scale of inequality as it ignores the inequality present between the intervening deciles. The SII better represents the magnitude of the absolute inequality in HLE between more and less deprived areas, as it reflects the experiences of the whole population. It is, therefore, more sensitive to changes in the socioeconomic profile of all areas (Low and Low, 2004). SII can be interpreted as the range in HLE between the most and least deprived parts of the population, based on the line of best fit.

In 2011, lower super output areas (LSOA) boundaries were revised, creating 32,844 LSOAs from the original 32,482 (based on 2001 boundaries). As a result of these boundary changes LSOAs have either remained unchanged, merged, split or had complex changes. To take account of these changes adjusted IMD 2010 (PHE, 2013) scores were applied using a formulation developed by Public Health England. IMD 2010 has been used in this publication as ONS are currently investigating the impact in moving to the IMD 2015 score and will look to revise all time point estimates based on the IMD 2015 scores. LSOAs were ranked using these adjusted scores and aggregated into 10 groups or “deprivation deciles” based on their ranking, with approximately equal numbers of LSOAs in each. The most deprived tenth were allocated to decile 1 and the least deprived to decile 10, with the intervening deciles having levels of exposure on a gradient between these extremes. This statistical bulletin assesses HLE in the private household population across these 10 groupings of areas by gender and quantifies the inequality between them in absolute terms using the range and SII.

Measuring differences in health states between populations exposed to different levels of deprivation allows health organisations to make informed decisions about the level of intensity with which preventive actions designed to improve health should be focused (Institute of Health Equity, 2010). It also enables organisations to understand the benefit to the wider economy in terms of fitness for work and extending the working lifespan.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys13. Methods

Calculating healthy life expectancy

The data used in calculating the prevalence of “Good” general health was obtained from the annual population survey (APS). It was aggregated over a 3-year period to achieve sufficiently large sample sizes to enable meaningful statistical comparison.

However, as the size of each upper tier local authority (UTLA) varies, the number of respondents sampled in some UTLAs was a lot smaller than for others. For these authorities with relatively small sample sizes, such as the London borough of Tower Hamlets, the estimates are more susceptible to large fluctuations because of the impact of random variation.

The prevalence of “Good” general health among males and females resident in private households in England was compared across regions and UTLAs. UTLAs include unitary authorities, London boroughs and metropolitan districts in England, but excludes the City of London and the Isles of Scilly due to insufficient population size. HLE was then calculated using the Sullivan method, which combines prevalence data with mortality and mid-year population estimates (MYPE) over the same period and geographical coverage to calculate estimates of life expectancy (LE) and healthy life expectancy (HLE) at birth and age 65 by sex (ONS Life Table Template, Jagger et al., (2007).

The prevalence of “Good” general health among males and females was also compared across aggregations of lower super output areas (LSOAs) to deprivation deciles. LSOAs are classified in the super output area classification of statistical geographies. They were originally established in 2004 and cover populations of between 1,000 and 3,000 (400 to 1,200 households) (ONS). LSOAs were allocated to deprivation deciles by allocating each one their deprivation score as measured by the English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) and using these scores to rank the areas and divide into 10 groups with approximately equal numbers of LSOAs in each.

The APS provides prevalence information for those aged 16 years and over. We are able to estimate HLE at birth by directly imputing health prevalence at age 16 to 19 for those under 16 (ONS, 2013).

The age band structure used for calculating healthy life expectancy (HLE) is not that outlined in the update to methodology to calculate health expectancies (ONS, 2013) but the traditional age band structure of <1, 1 to 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19……85 and over.

Results are presented with 95% confidence intervals in reference tables to help interpretation. Confidence intervals in this statistical bulletin indicate the uncertainty surrounding HLE estimates and allow more meaningful comparisons between areas. When comparing the estimates of 2 areas, non-overlapping confidence intervals are indicative of statistical significance but to confirm this, a test of significance should be carried out. When the statistical significance is noted in the text, this is based on a statistical test of the differences (Jagger et al., 2007). All differences noted in this text have been calculated to more than 1 decimal place.

Quality information about ONS health expectancies is available on our website.

Slope index of inequality

The slope index of inequality (SII) was used to assess the absolute inequality in HLE between the least and most deprived deciles. This indicator measures the gap in HLE by taking into account the inequality across all adjacent deciles of relative deprivation, rather than focusing only on the extremes.

To calculate the slope index of inequality:

Deciles were ordered by decreasing area deprivation, that is, from the most to the least deprived. The fraction of the total population in each decile (f) was calculated. The cumulative frequency (ci), that is the cumulative sum of the population in successively less deprived deciles, was also obtained and the relative deprivation rank (x) for each decile was calculated as:

Equation for relative deprivation rank

Download this image Equation for relative deprivation rank

.png (789 B)This formula calculates the relative deprivation rank for use in the slope index of inequality calculation.

The SII (slope of the regression line) was then estimated by regressing HLE for each decile against the relative deprivation rank (x), weighted by the population in each decile.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys14. Uses and users

Life expectancy (LE) has increased considerably since the 1980s and is expected to increase further (ONS 2015b). However, it is important that the number of years lived in “Good” health rises faster or at the same rate. If not, then these additional years of life are being spent in poor health and greater dependency, putting additional strain on health and social care resources. Health expectancies are therefore used to monitor whether the “extra” years gained are spent in favourable health.

The questions used to calculate healthy life expectancy (HLE) are in part subjective, with responses being influenced by an individual’s expectations. Clear differences have been observed in HLE by socio-demographic factors such as age, sex, socio-economic position (ONS 2010) and area deprivation.

However, self-assessed general health and limiting persistent illness (ONS, 2014b, Manor et al., 2001) are linked to more objective measures of health and have been shown to have value in predicting health care need or usage and subsequent mortality. Research evidence indicates people with poor self-assessed health (both general health and limiting persistent illness) die sooner than those who report their health more positively (Mossey and Shapiro, 1982; Idler and Benyamini, 1997; Miilunpalo et al., 1997; DeSalvo et al., 2006; Bopp et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2012).

Survey measurements of general health and limiting persistent illness are used globally to identify health inequality between administrative areas, inform unmet care and health service needs and to target and monitor health care resource allocation amongst population groups (Marmot, 2010). International organisations and networks such as the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2011), Eurostat (Eurostat, 2013) and the Reves network on health expectancy use this information to compare morbidity across countries and to monitor trends over time.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys15. Feedback

If you have any comments or suggestions, we’d like to hear them. Please email us at hle@ons.gov.uk.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys