Cynnwys

1. Key findings

The inequality in life expectancy between the local areas with the highest and lowest figures decreased for only males at birth between 2000–02 and 2010–12.

The majority of local areas in Scotland (72%) were in the fifth of local areas in the UK with the lowest male and female life expectancy at birth in 2010–12. Conversely, only 15% of local areas in England were in this group.

None of the local areas in Scotland and Wales and only one in Northern Ireland were in the fifth of areas with the highest male and female life expectancy at birth in UK. In contrast, a quarter of local areas in England were in this group.

In 2010–12, male life expectancy at birth was highest in East Dorset (82.9 years) and lowest in Glasgow City (72.6 years).

For females, life expectancy at birth was highest in Purbeck (86.6 years) and lowest in Glasgow City (78.5 years).

Approximately 91% of baby boys in East Dorset and 94% of girls in Purbeck will reach their 65th birthday, if 2010–12 mortality rates persist throughout their lifetime. The comparable figures for Glasgow City are 75% for baby boys and 85% for baby girls.

Life expectancy at age 65 was highest for men in Harrow, where they could expect to live for a further 20.9 years compared with only 14.9 years for men in Glasgow City.

For women at age 65, life expectancy was highest in Camden (23.8 years) and lowest in Glasgow City (18.3 years).

2. Summary

This bulletin presents male and female period life expectancy at birth and at age 65 for the United Kingdom and local areas within the four constituent countries. Figures are presented for the period 2010–12, with those for the periods 2006–08 to 2009–11 for comparison purposes. Information is given about the context, calculation and interpretation of life expectancy figures.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Background

Period life expectancy at a given age for an area is the average number of years a person would live, if he or she experienced the particular area’s age-specific mortality rates for that time period throughout his or her life.

Life expectancy at birth has been used as a measure of the health status of the population of England and Wales since the 1840s. It was employed in some of the earliest reports of the Registrar General to illustrate the differences in mortality experienced by populations in different parts of the country. This tradition of using life expectancy as an indicator of geographic inequalities in health has been continued by ONS since 2001 with the publication of sub-national life expectancy statistics.

Several studies have shown that geographical variations in life expectancy can largely be accounted for by individual and area based deprivation. For example, using an employment and income based measure, Griffiths and Fitzpatrick (2001) (1 Mb Pdf), established that there was a strong association between deprivation at local authority level in England and life expectancy. They found that decreasing life expectancy was associated with increasing deprivation and that this association was stronger for males than for females. Similarly, Woods, et al. (2005) examined variations in life expectancy at birth across English regions and in Wales, concluding that the geographical patterns observed were largely explained by variations in income deprivation.

More recently, analyses of life expectancy at birth by socioeconomic position (129.1 Kb Pdf) have reported a clear gradient. Boys whose parent(s) had an occupation classified as ‘Higher managers and professionals’, such as directors of major organisations, doctors and lawyers, could be expected to live 5.8 years longer than boys whose parents were classified to ‘Routine’ occupations such as labourers and cleaners (ONS, 2011).

Furthermore, the Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010 (Marmot, 2010) reported that people living in the poorest neighbourhoods in England, will, on average, die seven years earlier than those living in the richest neighbourhoods.

These studies provide a compelling case for monitoring inequalities in life expectancy with a view to narrowing the gap between different areas. As noted by Marmot (2010), reducing health inequalities would benefit society in many ways. There would be economic benefits in reducing losses from illness associated with health inequalities. These currently account for productivity losses, reduced tax revenue, higher welfare payments and increased treatment costs.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Users and policy context

Life expectancy figures are widely used by local health planners in monitoring health inequalities and in targeting resources to tackle these inequalities in the most effective manner. They also help to inform policy, planning and research in both public and private sectors in areas such as health, population, pensions and insurance. Key users include the Department of Health and Public Health England, devolved health administrations, local and unitary authorities, and private pensions and insurance companies.

In England, the Department of Health’s Public Health Outcomes Framework, 2013–2016 Healthy lives, healthy people: Improving outcomes and supporting transparency (Department of Health, 2013) sets out its vision for public health, desired outcomes and the indicators that will help in understanding how well public health is being improved and protected. This framework uses the difference in life expectancy and healthy life expectancy between communities as one of two high level outcomes for monitoring population health. Similarly, the NHS Outcomes Framework 2013/14 (Department of Health, 2012) includes an objective to prevent people from dying prematurely. One of the two overarching indicators used to measure and monitor this objective is life expectancy at age 75.

In Wales, life expectancy is used as a high level indicator in the Public Health Strategic Framework - Our Healthy Future (OHF) - to monitor progress against reducing inequities in health.

At an international level, life expectancy is used by the European Community Health Indicators Monitoring (ECHIM) project to monitor health across Europe. In addition, life expectancy at birth, age 45 and age 65, and by socioeconomic status are also used as indicators of access to care (including inequity in access to care) and inequalities in outcomes in the European commission’s policy framework on Social Inclusion and Social Protection.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. National life expectancy

The interim life tables, 2010-12 (ONS, 2014) provide life expectancy figures for the United Kingdom and its four constituent countries. They are calculated using complete life tables (based on single year of age) for three-year rolling periods. The national life expectancy figures included in this statistical bulletin were calculated using the same methodology (abridged life tables method) used for sub-national life expectancy figures and should be used when making national and sub-national comparisons (see the ‘Methods’ section for more information). The difference in methodology means that the two sets of national figures may differ very slightly.

Life expectancy at birth

Life expectancy at birth in the UK increased between 2006–08 and 2010–12, from 77.5 to 78.9 years for males and 81.7 to 82.7 years for females.

Life expectancy was higher in England than in any of the other UK countries in every period examined. In England, male life expectancy increased from 77.9 years in 2006–08 to 79.2 years in 2010–12. For females, the corresponding increase was from 82.0 to 83.0 years. Over the same period, life expectancy at birth in Scotland, the country with the lowest figures, increased from 75.1 to 76.6 years for males and from 79.9 to 80.8 years for females.

All four UK countries saw increases in life expectancy over time albeit to varying extents. The greatest increase since 2000–02 was observed in Scotland for males (3.3 years) and in England for females (2.4 years). Conversely, the smallest increase was in Northern Ireland for males (2.6 years) and Scotland for females (2.0 years).

In each country, the increase in life expectancy was greater for males than for females, causing the difference between the sexes to narrow over time.

Table 1: Life expectancy at birth: by sex and country, 2006-08 to 2010-12

| United Kingdom | |||||

| Years | |||||

| Country | 2006-08 | 2007-09 | 2008-10 | 2009-11 | 2010-2012 |

| Males | |||||

| United Kingdom | 77.5 | 77.8 | 78.1 | 78.6 | 78.9 |

| England and Wales | 77.8 | 78.1 | 78.4 | 78.8 | 79.1 |

| England | 77.9 | 78.2 | 78.5 | 78.9 | 79.2 |

| Wales | 77.0 | 77.2 | 77.6 | 78.0 | 78.2 |

| Scotland | 75.1 | 75.4 | 75.9 | 76.3 | 76.6 |

| Northern Ireland | 76.4 | 76.8 | 77.1 | 77.6 | 77.8 |

| Females | |||||

| United Kingdom | 81.7 | 82.0 | 82.2 | 82.6 | 82.7 |

| England and Wales | 81.9 | 82.2 | 82.4 | 82.8 | 82.9 |

| England | 82.0 | 82.3 | 82.5 | 82.9 | 83.0 |

| Wales | 81.3 | 81.5 | 81.8 | 82.2 | 82.2 |

| Scotland | 79.9 | 80.1 | 80.4 | 80.7 | 80.8 |

| Northern Ireland | 81.3 | 81.4 | 81.6 | 82.0 | 82.3 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Three year rolling averages, based on deaths registered in calendar years and mid-year population estimates. | |||||

| 2. Figures for England and Wales include deaths of non-residents. Figures for England and Wales separately exclude deaths of non-residents. | |||||

| 3. Figures for 2002 to 2010 are based on mid-year population estimates, revised in light of the 2011 Census. | |||||

Download this table Table 1: Life expectancy at birth: by sex and country, 2006-08 to 2010-12

.xls (28.7 kB)Life expectancy at age 65

For men at age 65, UK life expectancy increased from 17.5 years in 2006–08 to 18.2 years in 2010–12. For women, the comparable increase was from 20.2 years to 20.9 years over the periods.

In the UK, life expectancy at age 65 was highest in England and lowest in Scotland.

In England, life expectancy for men at this age increased from 17.6 years in 2006–08 to 18.6 years in 2010–12. For women, the corresponding increase was from 20.3 to 21.1 years over the periods. The gender difference in life expectancy narrowed slightly over these periods.

In Scotland, life expectancy for men at age 65 increased from 16.3 years in 2006-08 to 17.2 years in 2010-12. For women, the corresponding increase was from 18.9 years to 19.5 years.

Table 2: Life expectancy at age 65: by sex and country, 2006-08 to 2010-12

| United Kingdom | |||||

| Years | |||||

| Country | 2006-08 | 2007-09 | 2008-10 | 2009-11 | 2010-2012 |

| Males | |||||

| United Kingdom | 17.5 | 17.7 | 17.9 | 18.2 | 18.4 |

| England and Wales | 17.6 | 17.8 | 18.1 | 18.3 | 18.5 |

| England | 17.6 | 17.9 | 18.1 | 18.4 | 18.6 |

| Wales | 17.2 | 17.3 | 17.6 | 17.9 | 18.0 |

| Scotland | 16.3 | 16.5 | 16.8 | 17.0 | 17.2 |

| Northern Ireland | 16.9 | 17.2 | 17.4 | 17.8 | 17.9 |

| Females | |||||

| United Kingdom | 20.1 | 20.3 | 20.5 | 20.9 | 20.9 |

| England and Wales | 20.3 | 20.5 | 20.7 | 21.0 | 21.1 |

| England | 20.3 | 20.5 | 20.7 | 21.0 | 21.1 |

| Wales | 19.9 | 20.1 | 20.2 | 20.5 | 20.6 |

| Scotland | 18.9 | 19.0 | 19.3 | 19.5 | 19.5 |

| Northern Ireland | 19.9 | 20.0 | 20.3 | 20.6 | 20.6 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Three year rolling averages, based on deaths registered in calendar years and mid-year population estimates. | |||||

| 2. Figures for England and Wales include deaths of non-residents. Figures for England and Wales separately exclude deaths of non-residents. | |||||

| 3. Figures for 2002 to 2010 are based on mid-year population estimates, revised in light of the 2011 Census. | |||||

Download this table Table 2: Life expectancy at age 65: by sex and country, 2006-08 to 2010-12

.xls (50.7 kB)6. Regional life expectancy

Life expectancy varied across English regions in each period examined and tended to be higher among those in the south than in the north and midlands.

Life expectancy at birth

In 2010–12, life expectancy at birth was highest in the South East (80.3 years) for males and in the South West for females (83.9 years). Conversely, these figures were lowest in the North West for males (77.7 years) and in the North East for females (81.6 years).

Life expectancy was higher for females than males across all regions in each period examined. In addition, this inequality in life expectancy between the sexes was consistently smaller in the South East and East of England than in any other region.

Life expectancy increased in each region between 2006–08 and 2010–12, with London experiencing the greatest improvement for both males (1.6 years) and females (1.2 years). Improvements in other regions varied between 1.1 and 1.5 years for males and 0.8 and 1.1 years for females.

A number of factors have been identified as plausibly being responsible for the excess mortality, and consequently lower life expectancy, in the northern regions of England. These include socioeconomic, environmental (including working conditions), educational, epigenetic, and lifestyle factors, which may act over the whole life course, and possibly over generations (Hacking, Muller and Buchan, 2011).

One factor that has received less attention is the selective migration of healthy individuals from poorer health areas into better health areas or vice-versa. This type of migration has been shown to play a significant role in increasing or decreasing location-specific illness and mortality rates, which then consequently impact on life expectancy figures. Norman, Boyle and Rees (2005) demonstrated that the largest absolute flow within England and Wales between 1971 and 1991 was of relatively healthy people moving from more deprived into less deprived areas. The impact of this migration was to raise ill-health and mortality rates where these people originated from and lower them in the destination areas. The authors also noted that the benefit to less deprived areas was reinforced by a significant group of people in poor health who moved from less to more deprived locations.

Evidence from the pattern of interregional migration between 1991 and 2010 (ONS, 2013a) also suggests that there might be a selective migration effect at play; there was a higher flow of people into southern regions than out while the reverse was the case in the North East and North West. However, it is not possible to quantify the extent to which better health areas are benefiting from selective migration of healthy people since the health status of these migrants is not known.

In a recent study, Hacking, Muller and Buchan (2011) examined trends in mortality across the north-south divide in England over a period of four decades. In addition to the excess deaths observed in northern regions throughout the period, they also noted that 14% of such deaths in 2004–06 were attributed to the prevalence of smoking while 3.5% in 2005 was associated with alcohol consumption. In addition, death rates for potentially avoidable causes, such as certain cancers, respiratory and heart disease, are significantly higher in northern regions than in the south (ONS, 2013b).

Table 3: Life expectancy at birth: by sex and region, 2006-08 to 2010-12

| England | |||||

| Years | |||||

| Region | 2006-08 | 2007-09 | 2008-10 | 2009-11 | 2010-12 |

| Males | |||||

| North East | 76.4 | 76.7 | 77.1 | 77.5 | 77.8 |

| North West | 76.4 | 76.6 | 77.0 | 77.4 | 77.7 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 77.1 | 77.4 | 77.7 | 78.1 | 78.3 |

| East Midlands | 77.8 | 78.1 | 78.3 | 78.7 | 79.1 |

| West Midlands | 77.2 | 77.5 | 77.9 | 78.4 | 78.7 |

| East | 78.9 | 79.2 | 79.5 | 79.9 | 80.1 |

| London | 78.1 | 78.5 | 78.8 | 79.3 | 79.7 |

| South East | 79.1 | 79.4 | 79.7 | 80.0 | 80.3 |

| South West | 78.9 | 79.1 | 79.4 | 79.8 | 80.0 |

| Females | |||||

| North East | 80.5 | 80.9 | 81.1 | 81.5 | 81.6 |

| North West | 80.6 | 80.8 | 81.1 | 81.5 | 81.7 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 81.3 | 81.4 | 81.7 | 82.0 | 82.2 |

| East Midlands | 81.8 | 82.0 | 82.3 | 82.8 | 82.9 |

| West Midlands | 81.6 | 81.9 | 82.2 | 82.6 | 82.7 |

| East | 82.7 | 83.0 | 83.2 | 83.6 | 83.7 |

| London | 82.6 | 82.9 | 83.2 | 83.6 | 83.8 |

| South East | 82.9 | 83.2 | 83.4 | 83.8 | 83.8 |

| South West | 83.0 | 83.2 | 83.4 | 83.7 | 83.9 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Three year rolling averages, based on deaths registered in calendar years and mid-year population estimates. | |||||

| 2. Figures exclude deaths of non-residents. | |||||

| 3. Figures for 2002 to 2010 are based on mid-year population estimates, revised in light of the 2011 Census. | |||||

Download this table Table 3: Life expectancy at birth: by sex and region, 2006-08 to 2010-12

.xls (51.2 kB)Life Expectancy at Age 65

In 2010–12, life expectancy at age 65 was highest for men in the South East (19.2 years), 1.5 years longer than in the North East with the lowest figure (17.6 years). For women, the comparable figures were 21.7 years in London and 20.0 years in the North East.

In contrast to at birth, the greatest improvement in life expectancy at age 65 between 2006–08 and 2010–12 was observed in the West Midlands for both sexes.

Gender inequality in life expectancy persists at age 65, albeit to a smaller extent than at birth. In addition, this inequality was smaller in the North East and North West than in other regions.

Table 4: Life expectancy at age 65: by sex and region, 2006-08 to 2010-12

| England | |||||

| Years | |||||

| Region | 2006-08 | 2007-09 | 2008-10 | 2009-11 | 2010-12 |

| Males | |||||

| North East | 16.6 | 16.9 | 17.1 | 17.5 | 17.6 |

| North West | 16.8 | 17.0 | 17.2 | 17.6 | 17.8 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 17.2 | 17.4 | 17.6 | 17.8 | 18.0 |

| East Midlands | 17.4 | 17.7 | 17.9 | 18.2 | 18.3 |

| West Midlands | 17.3 | 17.6 | 17.9 | 18.2 | 18.4 |

| East | 18.2 | 18.4 | 18.6 | 18.9 | 19.1 |

| London | 17.9 | 18.1 | 18.4 | 18.7 | 18.9 |

| South East | 18.4 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 19.0 | 19.2 |

| South West | 18.3 | 18.5 | 18.7 | 19.0 | 19.1 |

| Females | |||||

| North East | 19.2 | 19.4 | 19.6 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| North West | 19.3 | 19.5 | 19.8 | 20.1 | 20.2 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 19.8 | 20.0 | 20.2 | 20.5 | 20.5 |

| East Midlands | 20.1 | 20.4 | 20.6 | 20.9 | 21.0 |

| West Midlands | 20.1 | 20.4 | 20.6 | 21.0 | 21.0 |

| East | 20.7 | 20.9 | 21.1 | 21.5 | 21.5 |

| London | 20.8 | 21.1 | 21.3 | 21.6 | 21.7 |

| South East | 20.9 | 21.2 | 21.4 | 21.6 | 21.6 |

| South West | 21.1 | 21.2 | 21.4 | 21.6 | 21.7 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Three year rolling averages, based on deaths registered in calendar years and mid-year population estimates. | |||||

| 2. Figures exclude deaths of non-residents. | |||||

| 3. Figures for 2002 to 2010 are based on mid-year population estimates, revised in light of the 2011 Census. | |||||

Download this table Table 4: Life expectancy at age 65: by sex and region, 2006-08 to 2010-12

.xls (51.7 kB)7. Local area life expectancy

The local area life expectancy figures presented in this bulletin are based on the current geographical boundaries.

Life expectancy at birth

The local areas in the UK with the highest and lowest male and female life expectancy at birth for the periods 2000–02 to 2010–12 are presented in tables 5 and 6 respectively. For the purpose of this bulletin, figures are only presented for the top and bottom ten ranked local areas.

In 2010–12, male life expectancy at birth was highest in East Dorset (82.9 years) and lowest in Glasgow City (72.6 years). For females, life expectancy at birth was highest in Purbeck at 86.6 years and lowest in Glasgow City where females could expect to live for 78.5 years. These differences were statistically significant. It is noteworthy that these areas may not always be ranked top and bottom respectively in the UK. Therefore, the change in geographical inequality in life expectancy is not necessarily a measure of the change in the gap between specific areas over time. Nevertheless, Glasgow City was consistently ranked as the area with the lowest male and female life expectancy between 2000–02 and 2010–12.

Geographical inequality in life expectancy fell for males between 2000–02 to 2010–12 but not for females. The difference in male life expectancy between the local areas with the highest and lowest figures fell from 10.6 years in 2000–02 to 10.3 years in 2010–12. For females, the comparable difference increased from 7.7 years to 8.1 years over the periods.

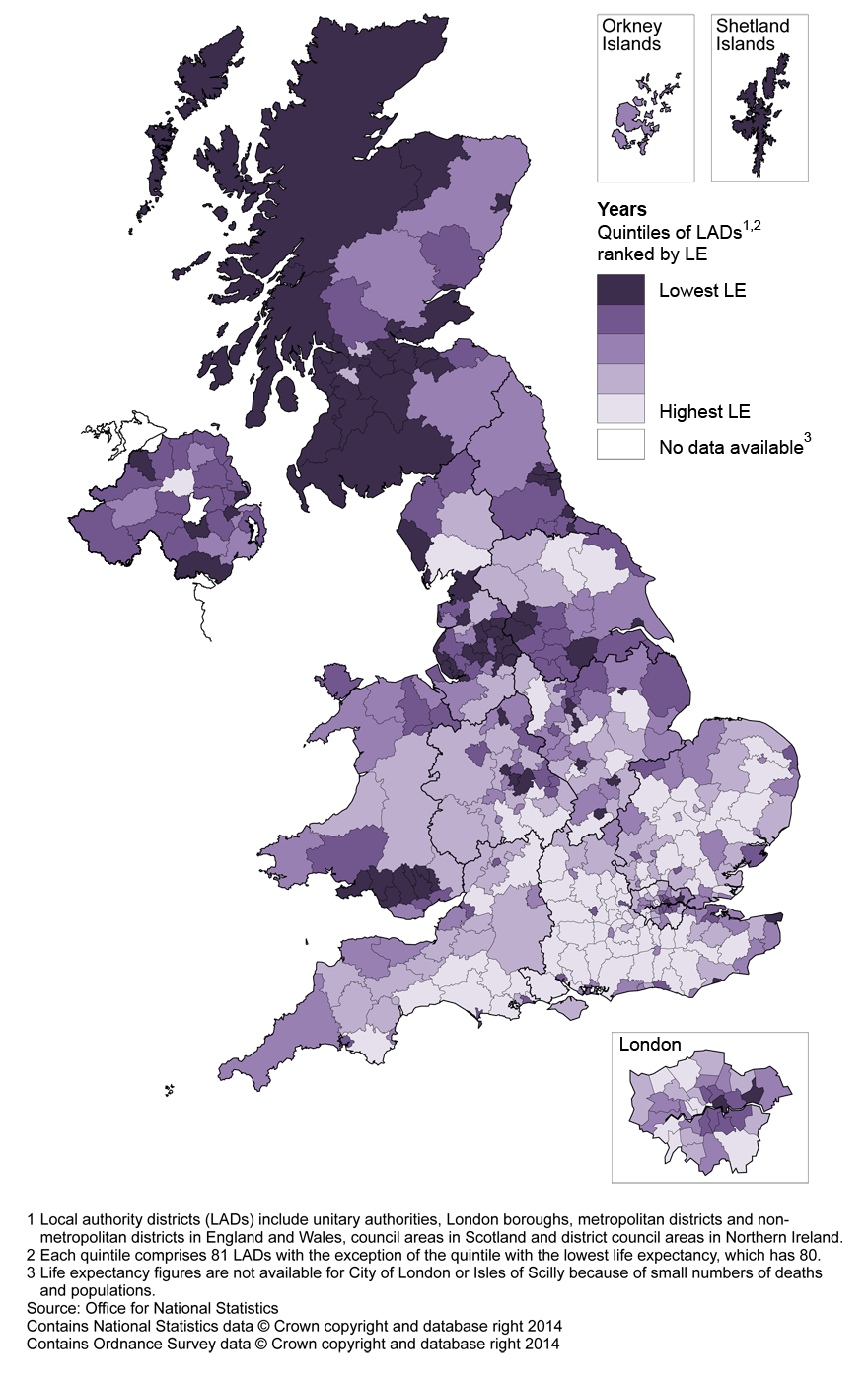

For males at birth, 72% of local areas in Scotland, 36% in Wales and 19% in Northern Ireland and only 14% of local areas in England were in the fifth of areas with the lowest life expectancy in 2010-12. Conversely, only one local area in Northern Ireland and none of the local areas Scotland and Wales were in the fifth of areas with the highest life expectancy while a quarter of local areas in England were in this group.

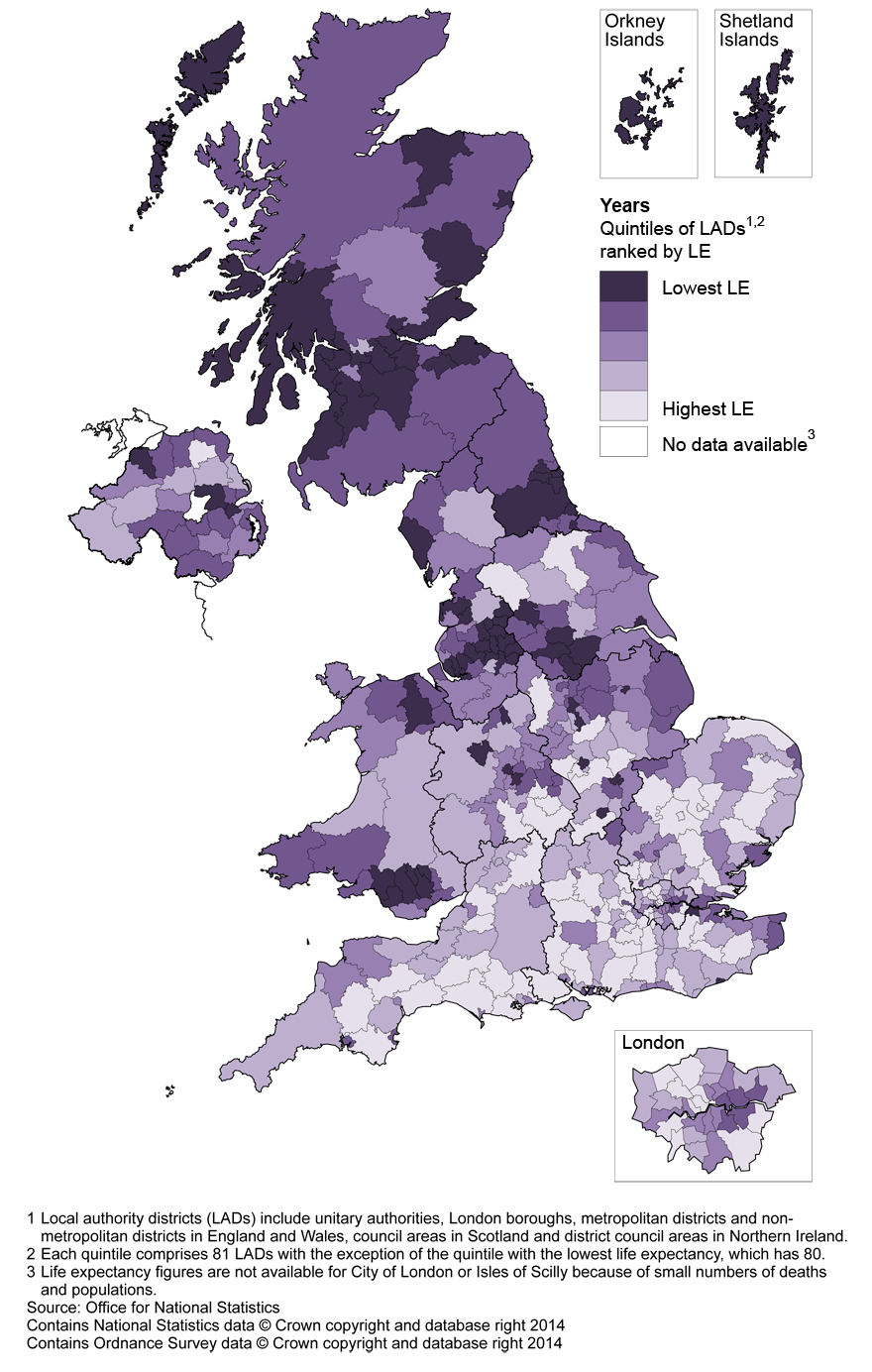

A similar picture was observed for females with 72% of local areas in Scotland, 32% in Wales, 12% in Northern Ireland and 15% in England fifth of areas with the lowest life expectancy. Again, a quarter of local areas in England were in the fifth of local areas in the UK with the highest life expectancy while only one in Northern Ireland and none in Scotland and Wales were in this group.

The distribution of male and female life expectancy at birth by local areas in the UK for 2010–12 can be found in maps 1 and 2 respectively below.

Map 1: Life expectancy (LE) for males at birth by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Local authority districts include unitary authorities, London boroughs, metropolitan districts and non-metropolitan districts in England and Wales; council areas in Scotland and district council areas in Northern Ireland.

- Each quintile comprises 81 LADs with the exception of the quintile with the lowest life expectancy, which has 80.

- Life expectancy figures are not available for City of London or Isles of Scilly because of small numbers of deaths and populations.

Download this image Map 1: Life expectancy (LE) for males at birth by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

.png (560.6 kB)

Map 2: Life expectancy (LE) for females at birth by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Local authority districts include unitary authorities, London boroughs, metropolitan districts and non-metropolitan districts in England and Wales; council areas in Scotland and district council areas in Northern Ireland.

- Each quintile comprises 81 LADs with the exception of the quintile with the lowest life expectancy, which has 80.

- Life expectancy figures are not available for City of London or Isles of Scilly because of small numbers of deaths and populations.

Download this image Map 2: Life expectancy (LE) for females at birth by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

.png (561.0 kB)Life expectancy at Age 65

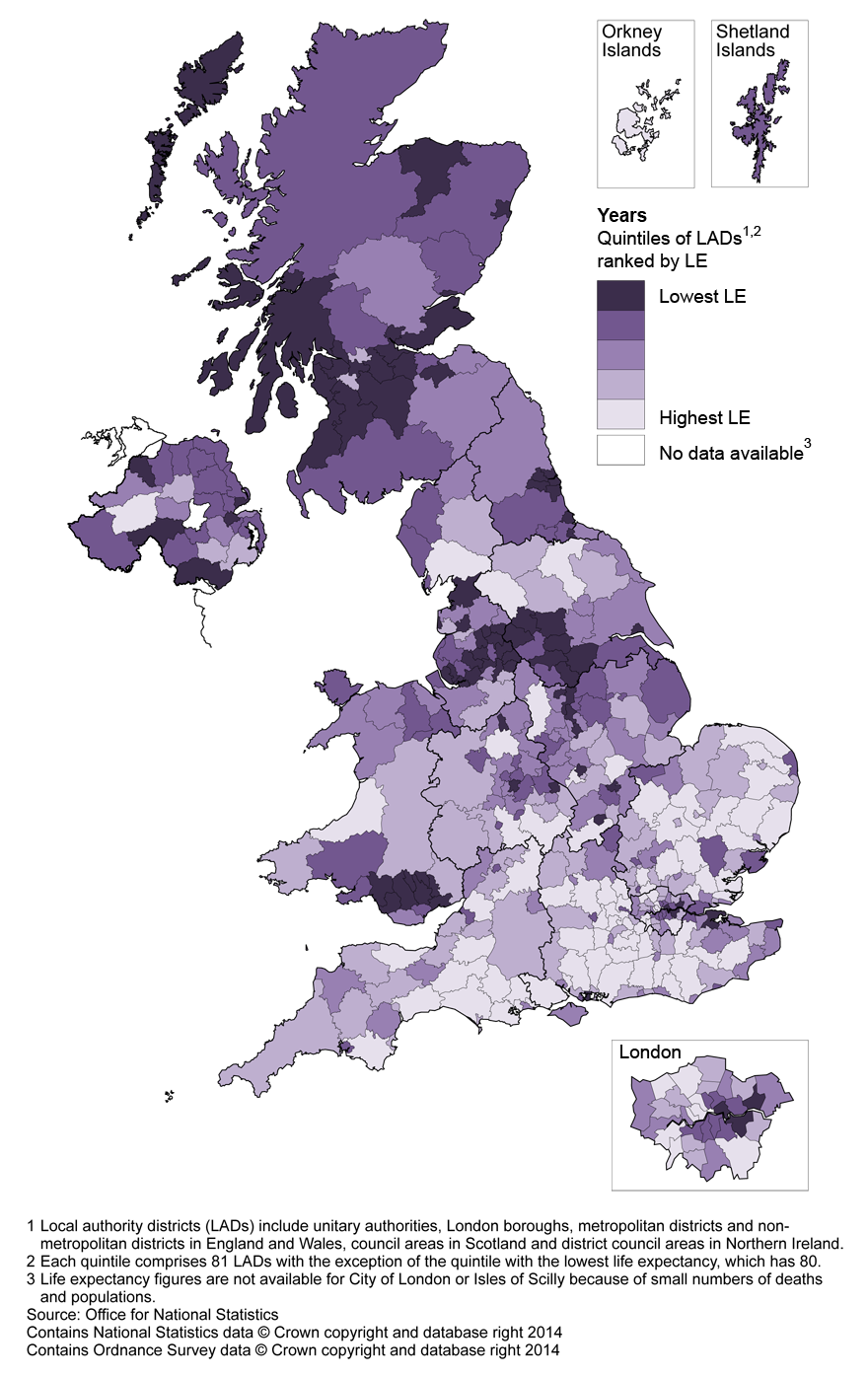

In 2010–12, life expectancy for men at age 65 was highest in Harrow (20.9 years) and lowest in Glasgow City (14.9 years).

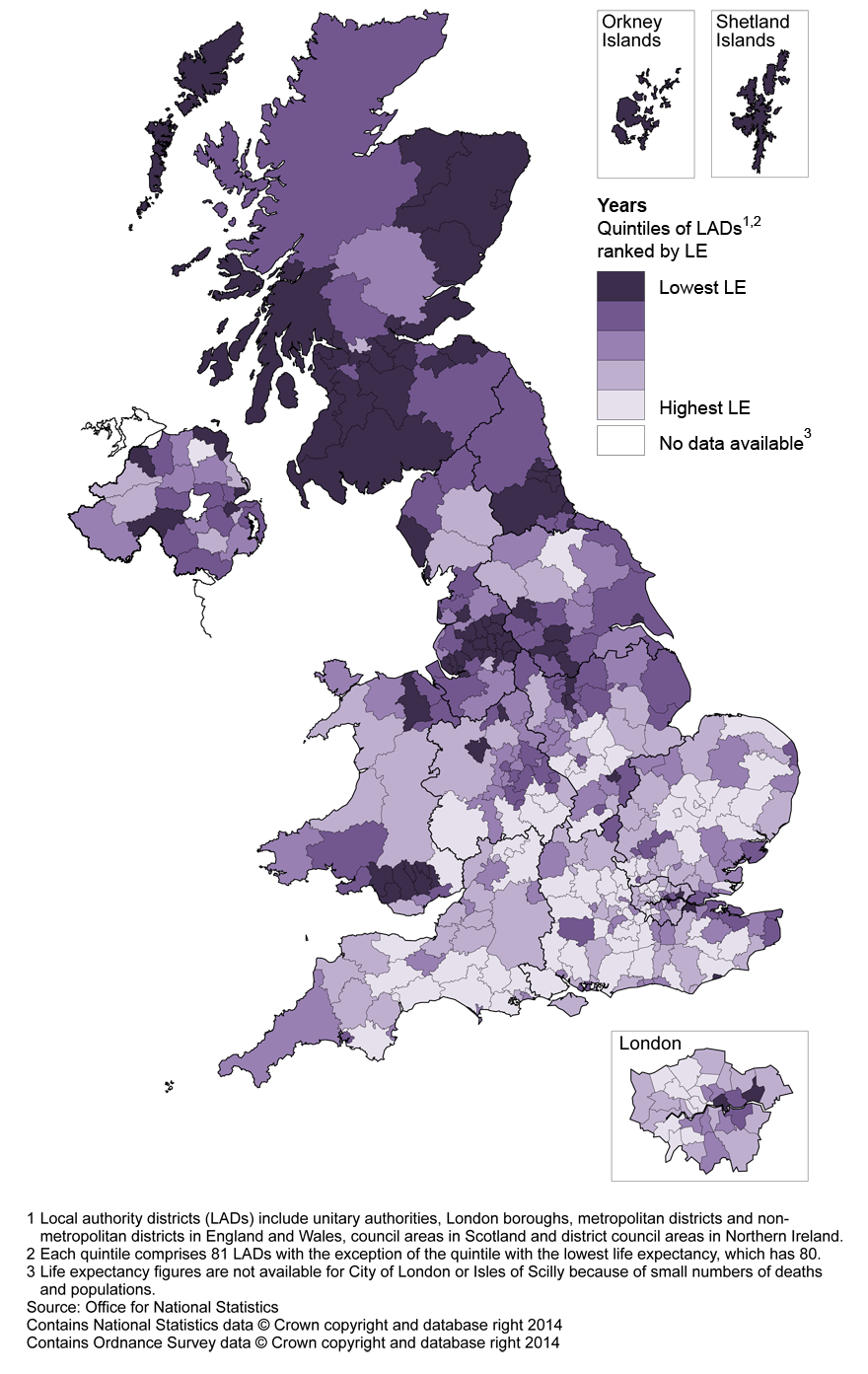

For women at this age, life expectancy was highest in Camden (23.8 years) and lowest in Glasgow City (18.3 years). These differences were statistically significant.

For both sexes, the geographical inequality in life expectancy at age 65 increased between 2000–02 and 2010–12. The difference between the local areas with the highest and lowest male life expectancy rose from 5.5 years in 2000–02 to 6.0 years in 2010–12. For females, the geographical inequality was 5.0 years in 2000–02 but rose to 5.5 years in 2010–12.

While national estimates of life expectancy provide a snapshot of the mortality experience of a whole population, they do not reveal the heterogeneity of experience within it. As such, favourable averages at national level or even at regional level may be disproportionately influenced by extremes of mortality experience within these areas. As observed from these figures, the inequality in life expectancy becomes more pronounced as the geographical level of analysis becomes more refined.

The distribution of male and female life expectancy at age 65 by local areas in the UK for 2010–12 can be found in maps 3 and 4 respectively below.

Map 3: Life expectancy (LE) for males at age 65 by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Local authority districts include unitary authorities, London boroughs, metropolitan districts and non-metropolitan districts in England and Wales; council areas in Scotland and district council areas in Northern Ireland.

- Each quintile comprises 81 LADs with the exception of the quintile with the lowest life expectancy, which has 80.

- Life expectancy figures are not available for City of London or Isles of Scilly because of small numbers of deaths and populations.

Download this image Map 3: Life expectancy (LE) for males at age 65 by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

.png (563.6 kB)

Map 4: Life expectancy (LE) for females at age 65 by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Local authority districts include unitary authorities, London boroughs, metropolitan districts and non-metropolitan.

- Each quintile comprises 81 LADs with the exception of the quintile with the lowest life expectancy, which has 80.

- Life expectancy figures are not available for City of London or Isles of Scilly because of small numbers of deaths and populations.

Download this image Map 4: Life expectancy (LE) for females at age 65 by local authority district, United Kingdom, 2010–12

.png (560.4 kB)8. Animated maps and reference tables

Life expectancy at birth and at age results for 2000–02 to 2010–12 have been published as a set of interactive animated maps to show the change in life expectancy at local area level over time.

The life expectancy results presented in this bulletin and additional results from 1991–93 can be found – presented with 95 per cent confidence intervals – in the following reference tables:

Reference table 1 – life expectancy at birth and at age 65 for the UK and local areas in England and Wales

Reference table 2 – life expectancy at birth and at age 65 for the UK and local areas in Scotland

Reference table 3 – life expectancy at birth and at age 65 for the UK and local areas in Northern Ireland

Reference table 4 – life expectancy at birth and at age 65 for the UK and constituent countries

Reference table 5 – top and bottom ten ranked local areas by life expectancy at birth and at age 65

9. Methods

Calculation

Abridged life tables (based on five-year age groups) were constructed using standard methods (Shyrock and Siegel, 1976; Newell, 1994). Separate tables were constructed for males and females using numbers of deaths registered in calendar years and annual mid-year population estimates. A life table template (192.5 Kb Excel sheet) which illustrates the method used to calculate life expectancy (and 95% confidence intervals) for this bulletin, including a description of the notation, can be found on the ONS website.

The 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) for each area was calculated using the revised Chiang method (Chiang II), allowing the calculation of the variance of the mortality rates for those age groups with no deaths registered in the analysis period. This method is the approved standard for ONS outputs of life expectancy at sub-national level (Toson and Baker, 2003 (288.1 Kb Pdf)).

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys10. Interpretation of life expectancy

All figures presented in this bulletin are period life expectancies. Period expectation of life at a given age for an area in a given time period is an estimate of the average number of years a person of that age would survive if he or she experienced the particular area’s age-specific mortality rates for that time period throughout the rest of his or her life. The figure reflects mortality among those living in the area in each time period, rather than mortality among those born in each area. It is not therefore the number of years a person in the area in each time period could actually expect to live, both because the death rates of the area are likely to change in the future and because many of those in the area may live elsewhere for at least some part of their lives.

Period life expectancy at birth is also not a guide to the remaining expectation of life at any given age. For example, if female life expectancy at birth was 80 years for a particular area, the life expectancy of women aged 65 years in that area is likely to exceed 15 years. This reflects the fact that survival from a particular age depends only on the death rates beyond that age, whereas survival from birth is based on death rates at every age.

Further information on period and cohort life expectancies can be found on the ONS website.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys11. Differences between period and cohort life expectancies

Expectations of life can be calculated in two ways: period life expectancy (as presented in this bulletin) and cohort life expectancy.

Cohort life expectancies are calculated using age-specific mortality rates which allow for known or projected changes in mortality in later years and are therefore regarded as a more appropriate measure of how long a person of a given age would be expected to live, on average, than period life expectancy.

For example, period life expectancy at age 65 in 2000 would be worked out using the mortality rate for age 65 in 2000, for age 66 in 2000, for age 67 in 2000, and so on. Cohort life expectancy at age 65 in 2000 would be worked out using the mortality rate for age 65 in 2000, for age 66 in 2001, for age 67 in 2002, and so on.

Period life expectancies are a useful measure of mortality rates actually experienced over a given period and, for past years, provide an objective means of comparison of the trends in mortality over time, between areas of a country and with other countries. Official life tables in the UK and in other countries that relate to past years are generally period life tables for these reasons. Cohort life expectancies, even for past years, usually require projected mortality rates for their calculation and so, in such cases, involve an element of subjectivity.

Further information on period and cohort life expectancies can be found on the ONS website.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys