1. Acknowledgements

Authors: Sami Hamroush, Rebecca Hendry and Michael Hardie

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions from Chloe Gibbs, Claire Dobbins, Rachel Jones, Laura Pullin and Ciaren Taylor.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Main points

Revised Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) estimates for 2013 and 2014 show that the amount the UK generated from its overseas foreign direct investment (credits) fell from £104.6 billion to £71.1 billion between 2011 and 2014.

The analysis shows that the decline in direct investment credits between 2011 and 2014 was entirely due to a fall in the rate of return generated by UK investments overseas; however, this was partly offset by a small rise in UK FDI assets.

In contrast, the amount overseas investors generated on UK direct investment (debits) increased from £51.1 billion to £57.9 billion between 2011 and 2014.

The rise in UK direct investment debits reflected an increase in direct investment into the UK, which was partly offset by a fall in the rate of return.

A decrease in the value of credits and rise in debits resulted in the UK’s net foreign direct investment earnings falling from £53.5 billion to £13.2 billion over the period.

When the revised estimates of direct investment earnings are incorporated into Balance of Payments, if all other components are unchanged, the downward pressure they apply would show that the current account balance in 2014 widened to 4.5% of nominal GDP1. This would soften the latest published estimates of the current account, which currently report a deficit of 5.1% of nominal GDP.

Analysis of UK earnings by geographical region highlight that UK credits fell across the majority of regions, driven mainly by a fall in the rate of return. The EU accounted for a large proportion of the decline in UK FDI credits, accounting for £21.0 billion of the £33.5 billion decrease. A fall in the rate of return the UK generates in the EU was accompanied by disinvestment over the period.

The £6.8 billion increase in the value of debits reflected increased investment from all geographical regions, with the EU accounting for £6.1 billion. The rise in debits generated by the EU reflects increased investment into the UK from the region and a higher rate of return.

Analysis by economic activity shows that the largest decline in net UK earnings was from the production industries. The decline was driven by the manufacturing and mining & quarrying sub-industries. The fall in net FDI earnings from manufacturing reflected lower rates of return and disinvestment of overseas assets; while debits rose due to increased investment into the UK and increased rates of return. FDI earnings from the mining & quarrying industries reflect falls in the value of credits, due to lower rates of return.

Other industrial groupings reporting notable declines were transport, storage & communications; distribution, hotels & restaurants; and business services & finance.

Notes for Main points

- This assumes that all other components of the current account remain unchanged; however, when these data revised FDI more up-to-date information for other aspects of the current account will be available and potentially offset or exacerbate the upward pressure applied by incorporating revised FDI data for 2013 and 2014.

3. Introduction

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) refers to cross-border investments made by residents and businesses from one country into another, with the aim of a establishing a lasting interest in the company receiving investment1.

FDI statistics published by Office for National Statistics (ONS) cover all cross-border transactions: earnings, positions, and flows. FDI earnings refer to the earnings investments generate: these are referred to as credits for earnings on UK assets abroad, and debits for earnings made by a non-resident enterprises on assets held in the UK. Investment positions refer to the value of the stock of cross-border investment: UK owned assets abroad are referred to as UK assets; assets held in the UK by non-resident enterprises are described as UK liabilities. FDI flows refer to the financial flows from one country to another; these are mainly reflected in the change in investment position, and therefore will not be covered extensively this analysis.

The UK’s Current Account has remained in deficit for over three decades. The period between 1999 and 2005 saw the deficit narrow from 2.5% to 1.2% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), before widening in the years leading up to the 2008-09 economic downturn. Despite an improvement immediately following the downturn, the current account deficit deteriorated in all years between 2011 and 2014, reaching a record 5.1% of GDP in 2014, according to the latest published estimates. The deterioration since 2011 can largely be explained by FDI earnings, which accounted for 79.1% of the decline in the current account balance between 2011 and 2014, according to published estimates.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) published ‘An analysis of Foreign Direct Investment, the key driver of the recent deterioration in the UK’s Current Account’ on 30th October 2015. This article presented analysis on the key drivers behind the change in net FDI earnings and therefore the current account, with particular focus on: the performance of FDI with different economic regions, industries and firm size; the distributions of rates of return over time; and the effects of currency fluctuations. The article utilised data from the quarterly FDI survey for 2014 and annual FDI survey for 2013. The quarterly survey provides a timely first estimate of annual FDI, whereas the annual survey, which is less timely, utilises a larger sample size and allows companies to base their returns on fully audited annual accounts, instead of management accounts that are provided on a quarterly basis.

In December 2015, ONS published Foreign Direct Investment 2014, which included revised data for 2013 and first estimates for 2014 using data from the annual FDI survey for the first time. This article updates the geographical region and industry aspects of the analysis published 30 October 2015 with the most recent FDI data for 2013 and 2014. As previously communicated, these most recent estimates of FDI were not incorporated within the most recent Balance of Payments estimates, published on 23 December 2015. ONS will incorporate these data within the Balance of Payments at the earliest opportunity.

Analysis presented in this paper will focus on the revised FDI data for 2013 and 2014. When comparisons are made to the published BoP estimates, these will be referred to as the ‘latest published Balance of Payments estimates’; whereas indicative estimates of BoP that incorporate revised FDI data for 2013 and 2014 will be referred to as the ‘indicative Balance of Payments based on latest FDI estimates’.

Notes for Introduction

- An introduction to the concepts underpinning FDI and its relationship with Balance of Payments can be found here.

4. FDI and the current account

The current account measures the UK’s interaction with the rest of the world, and includes trade in goods & services; primary income, which includes FDI; and secondary income.

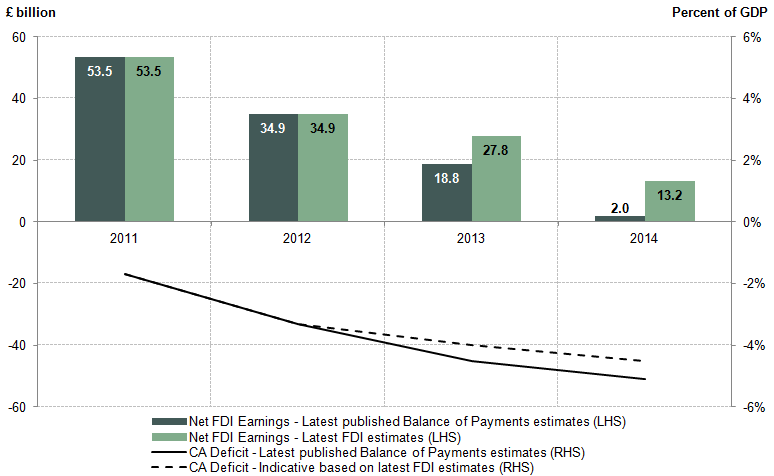

The indicative impact of incorporating the most recent FDI data for 2013 and 2014 into the Balance of Payments was outlined in - Coherence between Balance of Payments Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2015 and the FDI 2014 Bulletin, published 23 December 2015. Figure 1 shows that including these data result in net FDI earnings increasing from £18.8 billion to £27.8 billion in 2013 and from £2.0 billion to £13.2 billion in 2014. If all other components are held constant1, this would reduce the current account deficit as a percentage of nominal GDP, shown by the dotted black line, from a deficit of 4.5% to 4.0% in 2013 and 5.1% to 4.5% in 2014. The current account deficit in 2014 would still however remain the highest on record despite the upward pressure applied by incorporating the most recent annual FDI data.

Figure 1: UK Net FDI earnings and indicative impact on the current account deficit (% of GDP)

2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 1: UK Net FDI earnings and indicative impact on the current account deficit (% of GDP)

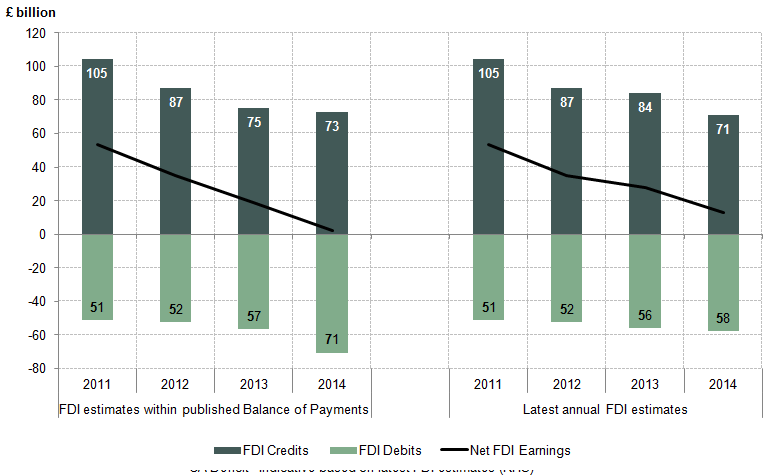

.png (26.7 kB) .xls (50.7 kB)The incorporation of the annual survey estimates for 2014 has resulted in a downward revision to UK credits from £72.6 billion to £71.1 billion and a downward revision to UK debits from £70.6 billion to £57.9 billion. Revised annual responses for 2013 have resulted in an upward revision to UK credits from £75.3 billion to £84.0 billion and a small downward revision to UK debits.

Figure 2: UK Net FDI earnings according to latest published Balance of Payments and latest FDI annual estimates, 2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 2: UK Net FDI earnings according to latest published Balance of Payments and latest FDI annual estimates, 2011 to 2014

.png (23.8 kB) .xls (18.9 kB)Incorporating revised FDI data for 2013 and 2014 are placed in context by analysing the longer term trends in the current account. The UK’s current account has remained in deficit for over three decades. The period between 1999 and 2005 saw the deficit narrow from 2.5% to 1.2% of GDP, before widening in the years leading up to the 2008-09 downturn, reaching 3.6% of GDP in 2008. The balance began to improve soon after the 2008-09 downturn, narrowing to 1.7% in 2011. More recently, the current account deficit deteriorated markedly in all years between 2011 and 2014.

Although the indicative impact of the revised FDI data result in the UK current account deficit softening from 4.5% to 4.0% in 2013 and 5.1% to 4.5% in 2014, the downward trend from 2011 remains.

Figure 3: UK indicative current account balance deficit

1984 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 3: UK indicative current account balance deficit

Image .csv .xlsWhile the 1989 deterioration in the current account deficit was mainly a result of a deteriorating trade position, the most recent deterioration in the current account can be almost fully attributed to the decline in the FDI income balance. The contribution of FDI to the current account balance, which has traditionally been positive, has fallen in each year since 2011, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: UK indicative current account balance and components

2006 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: UK indicative current account balance and components

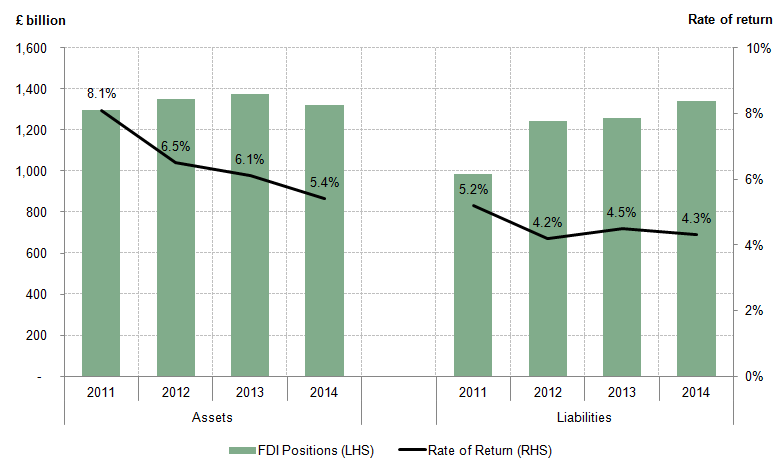

Image .csv .xlsChanges in FDI earnings can reflect a change in the rate of return2, a change in the stock of investment, or a combination of the two. Figure 5 presents the UK’s stock of assets and liabilities, along with each stock’s rate of return.

As the left side of the chart shows, the rate of return the UK generated on its overseas FDI assets fell from 8.1% to 5.4% between 2011 and 2014. The decline in the rate of return generated by assets accounted for the entire decline in credits, while the rise in assets over the period offset this slightly.

The rate of return on liabilities appears to have been more resilient, falling from 5.2% to 4.2% between 2011 and 2012, before stabilising at 4.5% and 4.3% in 2013 and 2014. The decline in the rate of return indicates that the increase in UK FDI debits was due to increases in the amount of overseas investment into the UK, with the fall in the rate of return partially offsetting this.

Figure 5: UK FDI positions and rates of return, 2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 5: UK FDI positions and rates of return, 2011 to 2014

.png (21.5 kB) .xls (38.4 kB)Notes for FDI and the current account

Indicative estimates shown in Figure 1 assume that all other components of the current account remain unchanged; however, when these data are incorporated more up-to-date information for other aspects of the current account will be available and potentially offset or exacerbate the upward pressure applied by incorporating revised FDI data for 2013 and 2014

Calculated by dividing earnings in any period by the stock of investment.

5. FDI by geographical region

Earnings

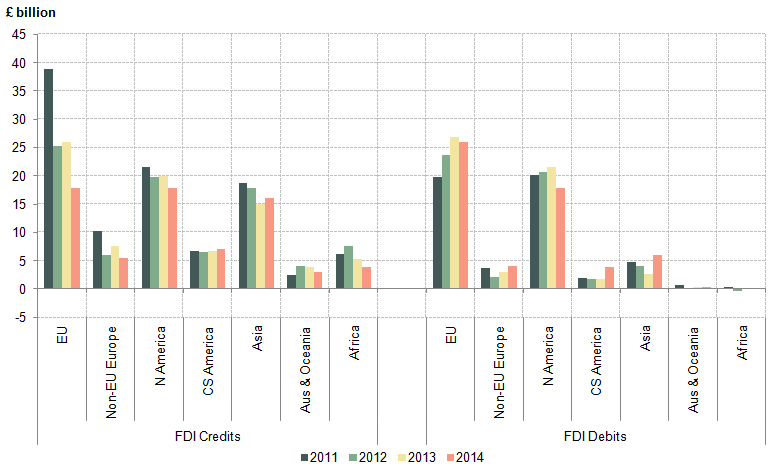

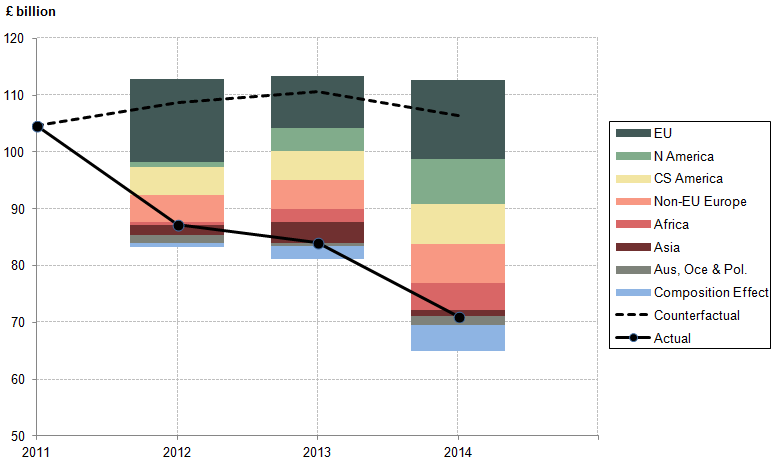

The value of UK FDI credits and debits are presented in Figure 6 by geographical region. The chart shows that the £33.5 billion decline in credits between 2011 and 2014 occurred across most regions, with the largest declines occurring in the EU and non-EU Europe, where credits fell by £21.0 billion and £4.8 billion respectively. Other regions also showing declines were North America (-£3.6 billion), Asia (-£2.7 billion), and Africa (-£2.3 billion).

The only regions reporting an increase in UK FDI credits between 2011 and 2014 were Australia, Oceania & Polar (£0.6 billion) and Central & South America (£0.3 billion).

Figure 6: UK Direct Investment Earnings by Geographical Region, 2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 6: UK Direct Investment Earnings by Geographical Region, 2011 to 2014

.png (13.6 kB) .xls (27.6 kB)Figure 6 also presents the value of UK direct investment debits by geographical region between 2011 and 2014, and helps identify which regions accounted for the £6.8 billion increase. Four of the seven regions show a rise in debits, with the largest increase accounted for by the EU, where debits rose by £6.1 billion. Other increases over the period occurred in South & Central America (£1.9 billion), Asia (£1.2 billion), and non-EU Europe (£0.4 billion).

The three regions where debits declined were to North America (-£2.4 billion), Australia, Oceania & Polar (-£0.3 billion), and Africa (-£0.3 billion).

Positions

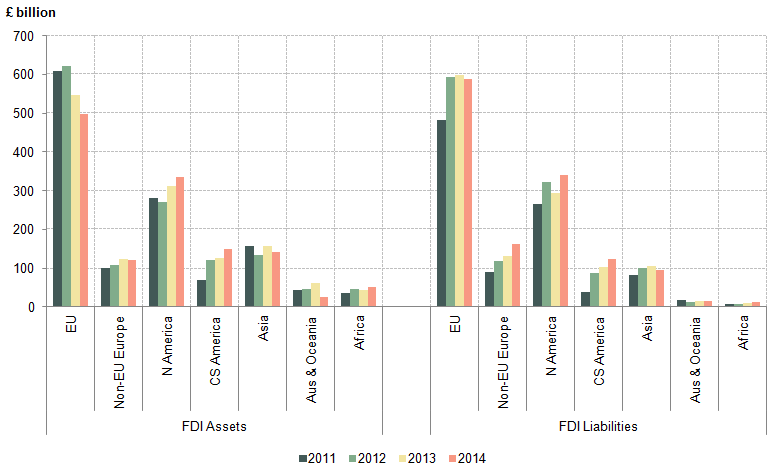

Figure 7 presents the value of UK FDI assets and liabilities between 2011 and 2014; analysing the change in the stock of investment held can indicate whether changes in earnings reflect a change in the stock of investment or a change in the rate of return, or a combination of both. For example, if the rate of return in a region remains constant and the stock of investment increases, the amount of FDI earnings would increase, and vice versa.

The rise in FDI assets from £1297.1 billion to £1320.0 billion between 2011 and 2014 reflected increases in the value of UK assets based in North America, from £279.8 billion to £334.4 billion; non-EU Europe, from £101.1 billion to £120.5 billion; South & Central America, from £70.2 billion to £148.4 billion; and Africa, from £36.2 billion to £51.6 billion.

Partly offsetting these increases was disinvestment in the EU, where the value of UK FDI assets fell from £609.1 billion to £497.4 billion. The UK also disinvested in Asia (£156.4 billion to £142.2 billion) and Australia, Oceania & Polar (£44.3 billion to £25.4 billion) over the same period.

Figure 7: UK Direct Investment Positions by Geographical Region, 2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 7: UK Direct Investment Positions by Geographical Region, 2011 to 2014

.png (13.4 kB) .xls (28.2 kB)In terms of liabilities, the amount of FDI into the UK increased across all economic regions, excluding Australia, Oceania & Polar, indicating increased appetite for UK investments internationally during this period. FDI liabilities grew from £481.1 billion to £588.9 billion from the EU; £90.7 billion to £163.4 billion from non-EU Europe; £266.5 billion to £340.9 billion from the North Americas; £39.6 billion to £123.3 billion from the South & Central Americas; £83.4 billion to £95.0 billion from Asia; and £6.6 billion to £12.8 billion from Africa.

Assets: stocks and rates of return changes

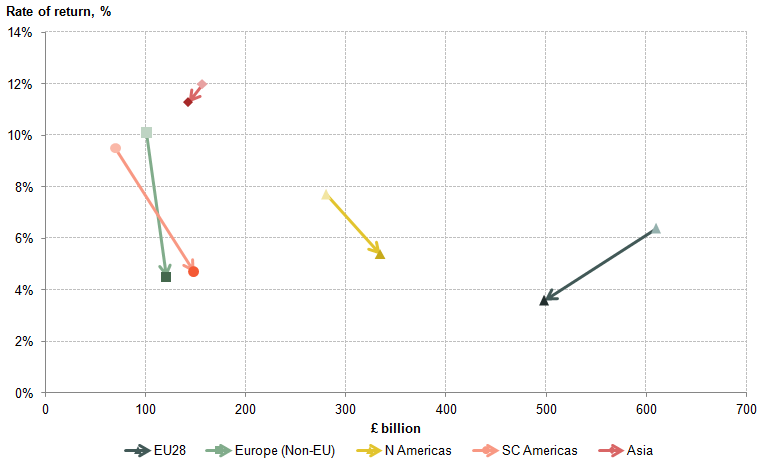

As previously mentioned, changes in direct investment earnings can reflect a change in the rate of return, a change in the stock of investment, or a combination of the two. Figure 8 presents these dynamics, showing both the stock of investment and rate of returns for the five largest investment regions in two periods of time: light data points indicate 2011, while darker ones indicate 2014. Shifts towards the horizontal axis indicate a declining rate of return, while shifts towards the vertical axis indicate disinvestment, and vice versa.

Figure 8 highlights that the decline in the value of UK FDI credits from the EU was partly due to disinvestment, as indicated by the EU shifting left from £609.1 billion to £497.4 billion; however, a further contributing factor has been the decline in the rate of return the UK generates on its EU based FDI assets, which fell from 6.4% in 2011 to 3.6% between 2011 and 2014. This decline in the rate of return on UK EU based assets explains approximately 66.1% of the decline in UK credits, with the remainder due to a stock change.

Figure 8: Movements in UK FDI assets and rates of return between 2011 and 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 8: Movements in UK FDI assets and rates of return between 2011 and 2014

.png (18.2 kB) .xls (38.4 kB)Similarly, the decline in credits from Asia is attributable not only to disinvestment, but also to a decrease in rate of return, from 12% to 11.3%. However, in contrast to the EU, where rates of returns explained the majority of the fall in credits, 63.1% of the decline in FDI earnings from Asia is explained by disinvestment1.

Declines in credits from other regions appear to have been entirely driven by falling rates of return rather than disinvestment – in fact, all remaining regions show that increased UK investment partially offset the decline in rates of returns; rates of return fell from 10.1% to 4.5% in Non-EU Europe and from 7.7% to 5.4% in North America.

The increase in UK FDI credits from South & Central America reflected a notable increase in investment, which more than offset the decline in the rate of return from 9.5% to 4.7% between 2011 and 2014.

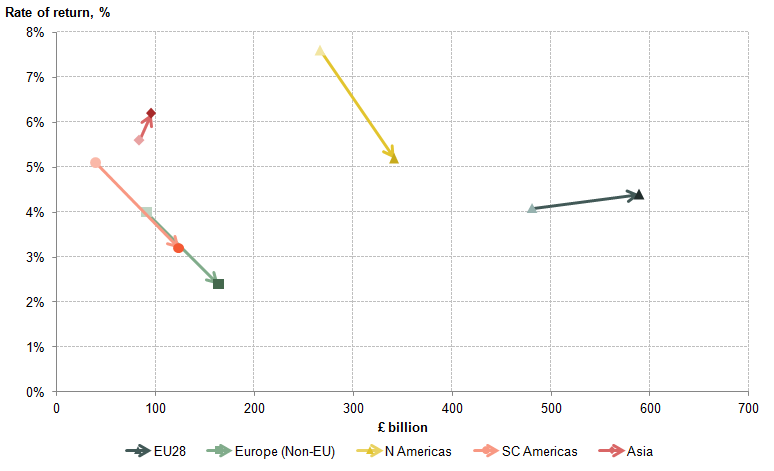

Liabilities: stocks and rates of return changes

Figure 9 repeats the same exercise but for debits, and highlights that the increase in the value of debits generated by EU investors in the UK between 2011 and 2014, was due to both an increase in UK investment, from £481.1 billion to £588.9 billion, and an increase in the rate of return, from 4.1% to 4.4%. Although both factors contributed to the rise in debits, increased investment accounted for almost three quarters of the increase in EU credits.

Similarly to the EU, the increase in debits generated by Asia on UK based FDI between 2011 and 2014 was due to a combination of both increased investment, from £83.4 billion to £95.0 billion, and an increase in the rate of return these assets generated, from 5.6% to 6.2%.

In contrast to the EU and Asia, increases in UK FDI debits to Non-EU Europe and Central & South America reflected increased investment between 2011 and 2014, with declines in rates of return over the period partially offsetting this.

The decline in UK FDI debits to North America between 2011 and 2014 is fully explained by a worsening rate of return, from 7.6% to 5.2%; partially offset by an increased investment.

Figure 9: Movement in UK FDI liabilities and rates of return between 2011 and 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 9: Movement in UK FDI liabilities and rates of return between 2011 and 2014

.png (19.1 kB) .xls (37.9 kB)FDI Earnings and the EU

It is worth noting that changes in FDI earnings between the UK and EU have had a notable impact on the UK’s overall FDI earnings balance. The EU accounted for £21 billion of the £33.5 billion overall decline in UK FDI credits, while also accounting for £6.1 billion of the £6.8 billion increase in FDI debits. Together, these changes worsened the UK’s FDI earnings balance with the EU – from a surplus of £19.1 billion in 2011 to a deficit of £8.0 billion in 2014. The deterioration with the EU alone represented 67.6% of the overall decline in net UK FDI earnings between 2011 and 2014, with the UK FDI earnings balance deficit with the EU in 2013 the first ever recorded, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: UK FDI credits, debits and balances with the EU, 2007 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 10: UK FDI credits, debits and balances with the EU, 2007 to 2014

Image .csv .xlsFigure 10 highlights that the majority of the deterioration in net UK FDI earnings with the EU between 2011 and 2014 was due to a decline in credits, which accounted for over three-quarters of the deterioration. This decline may partly reflect the challenging economic environment the EU has faced in recent years. In addition to the 2008 economic downturn, the EU encountered further economic headwinds as some eurozone governments required bailouts to meet sovereign debt repayments, resulting in slowing economic growth, and in some cases contracting, due to economic uncertainty and reductions in public expenditure.

Notes for FDI by geographical region

- Compared to a counterfactual scenario where rates of return are held constant.

6. Stock and rate of return impact on FDI earnings

The different impacts of changes in rates of return and stocks of investment have had on UK FDI often raise the question of how much of the decline in net earnings can be attributed to short-term and structural factors.

This question is difficult to answer both conceptually and technically, and requires some strong assumptions. An illustrative attempt can be made by making assumptions regarding what are considered the short-run and long-run effects. Rates of return investors generate on their FDI positions may be considered temporary – UK companies investing in the EU may expect rates of return to return to “normal” in the long-run, once economic headwinds they currently face come to pass. In contrast, the stocks of FDI positions investors hold may be considered structural – stocks are likely to take longer to rebuild once disposed of, or at least require a longer period of time to do so.

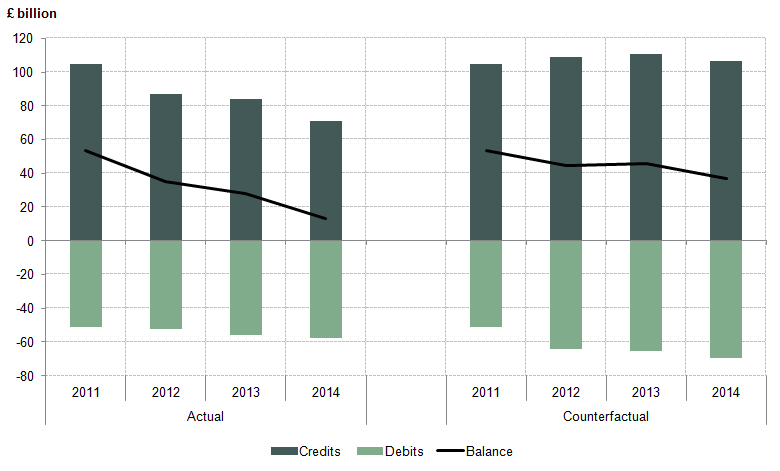

Using these assumptions allows for a counterfactual condition to be applied: what would UK FDI earnings look like if the returns FDI positions yielded in 2011 were held constant and the stock of FDI was allowed to change? Such a condition would result in changes in earnings only reflecting changes due to the stock of investment – assumed to have lasting structural effects in this exercise.

Two sets of FDI credits, debits and nets are presented in Figure 11, with the most recent FDI data presented on the left and the counterfactual scenario based on the discussed assumptions on the right. The assumptions result in two expected changes: first, the decline in credits between 2011 and 2014 does not occur under the counterfactual conditions: credits rise from £104.6 billion to £106.5 billion, rather than declining to £71.1 billion. This is due to the increase in the value of UK assets from £1,297.1 billion to £1,320.0 billion over the period. It is worth noting however, that UK FDI assets fell by £52.1 billion in 2014 compared to 2013, indicating a less temporary reduction to future earnings potential according to these assumptions.

Second, the value of debits rises from £51.1 billion to £69.5 billion when the counterfactual conditions are applied, rather than to £57.9 billion. This reflects the notable increase in the value of UK liabilities over the period, from £987.5 billion to £1,340.6 billion.

The net result of the changes in credits and debits is an improvement in the UK’s net FDI earnings, which fall from £53.5 billion to £37.0 billion between 2011 and 2014, rather than to £13.2 billion.

Figure 11: UK FDI earnings, actual and counterfactual totals, 2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 11: UK FDI earnings, actual and counterfactual totals, 2011 to 2014

.png (19.9 kB) .xls (27.1 kB)It is worth noting that the value of UK net FDI earnings still deteriorates even when rates of return are held constant; indicating that as much as 40.9% of the decline in direct investment earnings between 2011 and 2014 is structural – mostly due to the rise in UK FDI liabilities over the period.

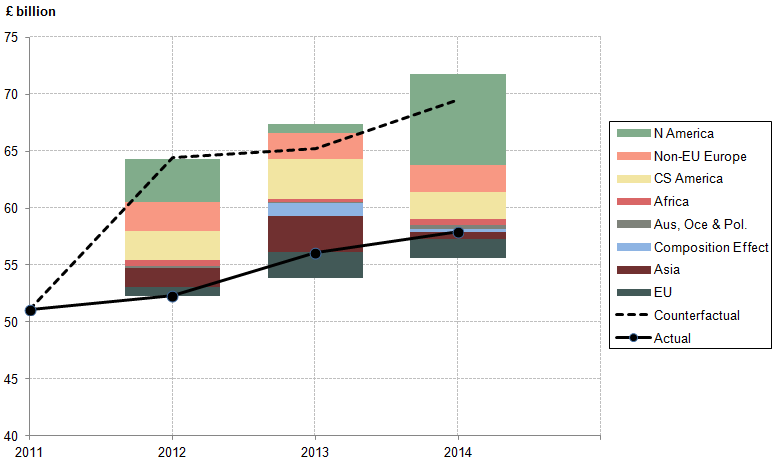

Analysis of these effects can also be conducted on a geographical basis. Figure 12 presents the UK’s FDI credits according to the latest FDI estimates as a solid line, and the UK’s counterfactual credits based on the assumptions discussed as a dotted line. The bars represent the short-run effects related to each geographical region – that is, the amount earnings would rise or fall by from each region if rates of return were held constant at 2011’s rates.

Figure 12: UK FDI credits, actual and counterfactual by geographical region, 2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 12: UK FDI credits, actual and counterfactual by geographical region, 2011 to 2014

.png (25.1 kB) .xls (49.2 kB)The largest geographical increase in credits when comparing the counterfactual scenario to actual credits comes from the EU; counterfactual credits decline from £38.9 billion to £31.8 billion between 2011 and 2014, rather than to £17.9 billion. This suggests that approximately £7.1 billion of the decline in UK FDI credits from the EU is due to stocks of investments, and assumed structural in this exercise.

Other increases in counterfactual compared to actual credits are from North America (+£7.8 billion), Central & South America (+£7.1 billion), non-EU Europe (+£6.8 billion), Africa (+£4.9 billion), Asia (+1.0 billion).

Credits from Australia, Oceania and Polar Regions decline by £1.6 billion when comparing the counterfactual scenario to the real world, reflecting rates of return the UK generate on assets based within the region increased between 2011 and 2014. There is also a compositional effect of -£4.5 billion in 2014, reflecting changes in the UK’s investment composition between 2011 and 2014 from low yielding regions to higher ones according to 2011 rates of return.

A similar exercise is repeated for debits in Figure 13, where counterfactual and real earnings can be compared on a geographical basis. The most notable increase from holding rates of return constant is with North America, where counterfactual debits rise from £21.5 billion to £25.7 billion between 2011 and 2014, rather than to £17.9 billion. This reflects notable falls in rates of return North American countries generated in the UK between 2011 and 2014, which fell from 7.6% to 5.2%, while the value of liabilities continued to increase, from £266.5 billion to £340.9 billion over the same period.

Other increases from holding rates of return constant are to non-EU Europe (+£2.4 billion), Central & South America (+£2.4 billion), Africa (+£0.5 billion) and Australia, Oceania and Polar Regions (+£0.3 billion).

The compositional effect is a positive £0.3 billion for debits in 2014, suggesting that regions which yielded the most lucrative rates of return on UK based investments in 2011 have decreased relative to lower yielding regions.

Decreases in debits from holding rates of return constant occurred to the EU (-£1.7 billion) and Asia (-£0.6 billion), reflecting that rates of returns investors from these regions generated in the UK, increased between 2011 and 2014.

Figure 13: UK FDI debits, actual and counterfactual by geographical region, 2011 to 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 13: UK FDI debits, actual and counterfactual by geographical region, 2011 to 2014

.png (25.1 kB) .xls (39.4 kB)7. FDI by economic activity

Overview of FDI earnings by economic activity

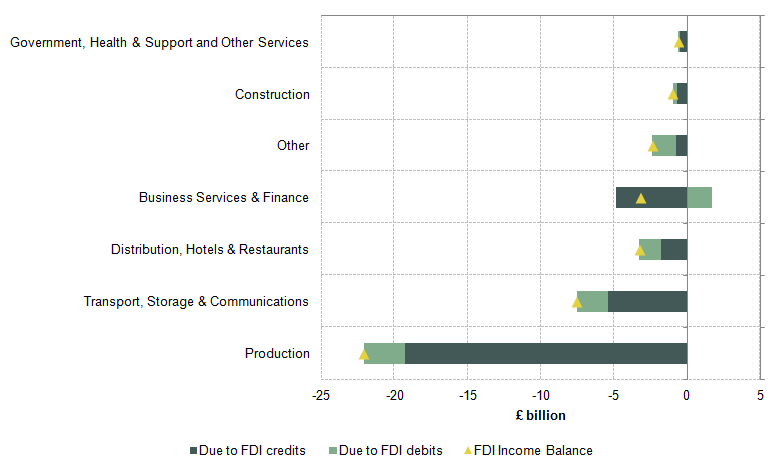

Changes in net UK FDI earnings by industry between 2011 and 2014 are presented in Figure 141, alongside the proportions of the change accounted for by credits and debits2.

Figure 14: Changes in UK FDI credits, debits and net between 2011 and 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 14: Changes in UK FDI credits, debits and net between 2011 and 2014

.png (15.2 kB) .xls (24.6 kB)Figure 14 illustrates that the four largest industrial groupings accounting for the £40.3 billion decrease in net FDI earnings between 2011 and 2014 were production (-£22.2 billion); transport, storage & communications (-£7.6 billion); distribution, hotels & restaurants (-£3.3 billion); and business services & finance (-£3.2 billion). It is worth noting that the majority of the deteriorations were due to falls in credits. Debits also applied some downward pressure to all industries excluding business services & finance; however, this was smaller relative to the impact credits had on net earnings.

As mentioned in the introductory section, this paper and the FDI 2014 statistical bulletin present revised FDI statistics for 2013 and first estimates for 2014 based on annual survey returns. The FDI revisions impact on the previous analysis of FDI earnings by industry between 2011 and 2014, published October 2015. The main impact on the change in net FDI earnings by industry is a reduction in the downward pressure applied by debits, and a reduction in the value of credits generated by business services & financial industries. Overall, the revisions result in improvements in net FDI earnings within most industrial groupings, excluding construction; government, health, support & other services; and business services & finance.

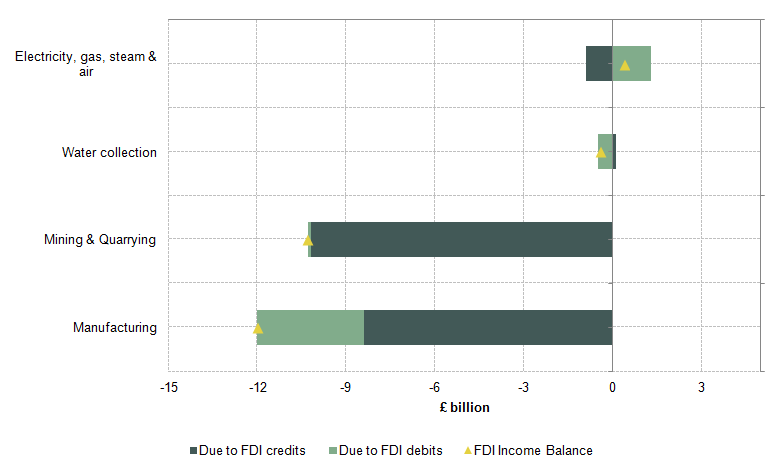

Production industries

The net earnings balance for the UK’s production industries, which consist of mining & quarrying; manufacturing; electricity, gas, stream & air; and water collection, has more than halved between 2011 and 2014. Figure 15 shows the contribution of the four sub-industries to the decline from a surplus of £34.9 billion in 2011 to £12.6 billion in 2014.

Figure 15: Changes in net UK FDI earnings in production by industry between 2011 and 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 15: Changes in net UK FDI earnings in production by industry between 2011 and 2014

.png (13.9 kB) .xls (27.1 kB)The majority of the decline in net earnings was due to declines in the manufacturing and mining & quarrying industries, with further negative contributions from water collection (-£0.4 billion). In contrast, net earnings from the electricity, gas, steam & air industries rose over the period (+£0.4 billion), partly offsetting the overall decline in production. The deterioration in both manufacturing and mining & quarrying was mainly as a result of falling credits; however, manufacturing was also impacted by an increase in UK debits.

UK credits from the manufacturing industry fell by £12.0 billion between 2011 and 2014 – this can mainly be attributed to a reduction in the rate of return from 8.4% to 6.5% and disinvestment of £36.7 billion over the period. Debits also increased due to improvements in the rate of return generated by overseas investors from the UK’s manufacturing industries (3.1% to 4.1%) and increased investment into the UK (£238.9 billion to £267.5 billion).

In contrast, the £10.3 billion fall in net FDI earnings from mining & quarrying can largely be attributed to a reduction in UK credits between 2011 and 2014. The stock of mining & quarrying assets remained stable at roughly £230 billion, but the rate of return fell from 8.8% to 6.1%, resulting in falling UK credits.

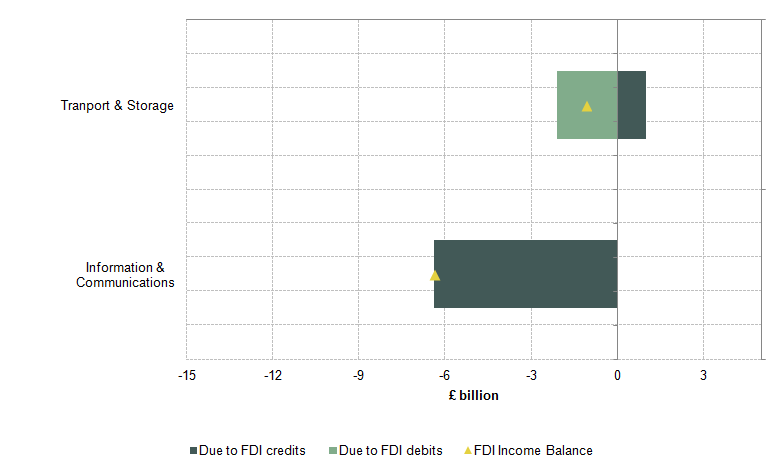

Transport, storage & communications

The value of UK FDI credits from the transport, storage & communications industrial grouping fell from £10.8 billion to £5.3 billion between 2011 and 2014, while the value of debits rose from £4.9 billion to £7.1 billion over the same period. These changes resulted in the UK’s net FDI earnings from these industries deteriorating from a surplus of £5.9 billion to a deficit of £1.8 billion over the period.

The transport, storage & communications broad industrial grouping comprises the information & communications industries3 and transport & storage industries4. The information & communications industries are the larger of the two, and accounted for 83.1% of the decline in the overall net earnings of the industrial grouping, with net earnings falling by £6.4 billion between 2011 and 2014, as shown in Figure 16. The transport & storage industries accounted for the remainder of the decline, falling £1.1 billion over the same period.

Figure 16: Changes in Net UK FDI Earnings in transport, storage & communications by industry between 2011 and 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 16: Changes in Net UK FDI Earnings in transport, storage & communications by industry between 2011 and 2014

.png (11.9 kB) .xls (18.4 kB)Net UK FDI earnings from the information & communications industries fell from a surplus of £6.1 billion to a deficit of £0.3 billion between 2011 and 2014. The majority of this decline occurred between 2011 and 2012, when credits fell by £8.3 billion to £1.4 billion. Debits also rose over this period, though had a smaller impact compared to credits.

The decline in credits the UK generates from its overseas information & communications industries between 2011 and 2014 reflected both disinvestment, from £177.0 billion to £147.1 billion, and a lower rate of return, from 5.6% to 3.2%.

It is worth noting that the majority of the decline in the rate of return appears to have occurred in 2012, when the rate of return fell to 1.4%, compared to 5.6% in 2011. This may reflect either disinvestment of lucrative assets over the period, a reallocation of assets from high yielding assets to lower yielding assets, or a decline in the rate of return of particular investments.

In terms of debits, the rise in the amount overseas investors generate on UK based information & communication investments appears to reflect a higher rate of return; partly offset by a decrease in the value of liabilities from £133.2 billion to £125.5 billion between 2011 an 2014.

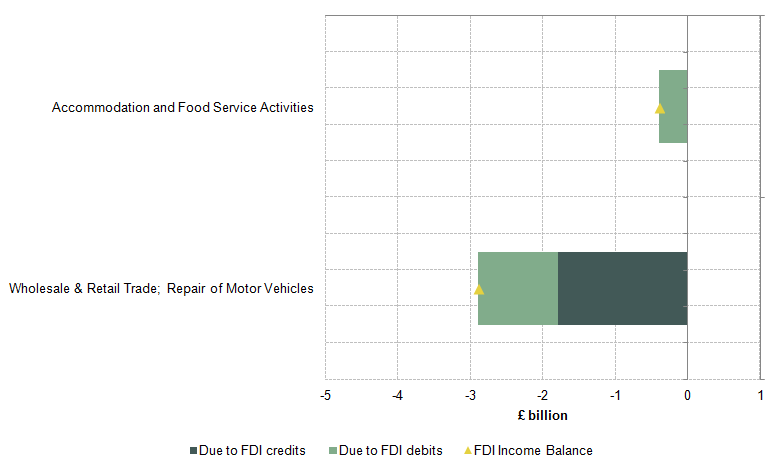

Distribution, hotels & restaurants

The value of UK FDI credits from the distribution, hotels & restaurants broad industrial grouping fell by £1.9 billion to £3.5 billion between 2011 and 2014, while the value of debits rose by £1.5 billion to £7.1 billion over the same period. The combined effect of these changes resulted in the UK’s FDI earnings balance deficit within these industries deteriorating, widening from £0.2 billion to £3.6 billion.

The distribution, hotels & restaurants broad industrial grouping comprises the wholesale, retail trade & repair of motor vehicles industries5 and the accommodation and food services activities industries6. The wholesale, retail trade & repair of motor vehicles industries are the larger of the two, and accounted for the majority of the decline in net earnings of the overall industrial grouping between 2011 and 2014 (85.3%), with the remainder accounted for by the accommodation and food services activities industries, as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17: Changes in net UK FDI earnings in distribution, hotels & restaurants by industry between 2011 and 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 17: Changes in net UK FDI earnings in distribution, hotels & restaurants by industry between 2011 and 2014

.png (10.9 kB) .xls (27.1 kB)The decline in net UK FDI earnings from the wholesale, retail trade & repair of motor vehicles industries reflected both a £1.8 billion decrease in credits and £1.1 billion increase in debits between 2011 and 2014, resulting in the balance deficit widening from £1.7 billion to £4.6 billion.

The decline in credits from the wholesale, retail trade & repair of motor vehicles industries was driven by a decline in the rate of return UK investors yielded on their overseas assets, which fell from 4.5% to 2.1% between 2011 and 2014. This was partly offset by increased investment over the period, with the value of assets rising from £86.1 to £98.5 billion over the same period.

The increase in debits from the wholesale, retail trade & repair of motor vehicles industries between 2011 and 2014 was driven by increased investment into the UK’s wholesale, retail trade & repair of motor vehicles industries, with liabilities rising from £117.3 billion to £155.5 billion over the period.

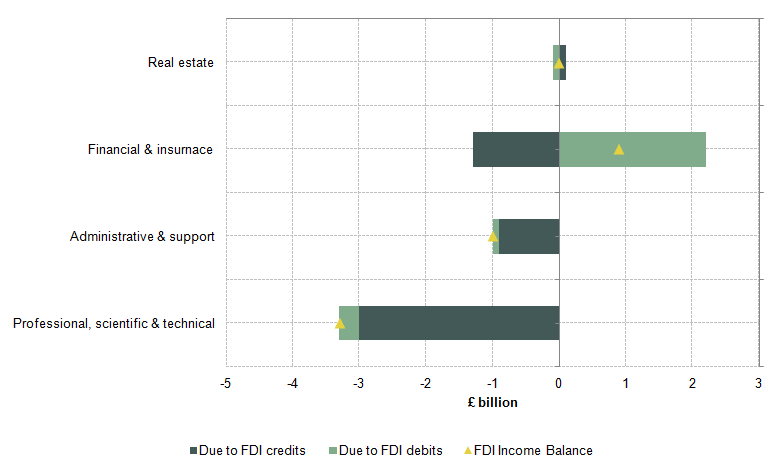

Business services & finance

Net FDI earnings from the business services and finance industries turned negative in 2014 due to a £4.9 billion fall in UK credits since 2011. This was partly offset by a £ 1.7 billion fall in UK debits over the period.

The fall in credits between 2011 and 2014 can be attributed to a reduction in the rate of return from 9.3% to 6.8%; partly offset by an increase in the value of the stock of assets held from £255.9 billion to £279.9 billion. The rate of return of UK liabilities also experienced a fall (9.2% to 4.8%) over this period, with increases in the stock of liabilities (£239.1 billion to £423.9 billion) partly offsetting this.

The business services and finance industrial grouping consists of professional, scientific & technical; administrative & support; real estate; and financial & insurance7. Figure 18 shows the change in the net FDI earnings for each of the components, broken down by the impact of credits and debits.

Figure 18: Changes in net UK FDI earnings in business services & finance by industry between 2011 and 2014

Source: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 18: Changes in net UK FDI earnings in business services & finance by industry between 2011 and 2014

.png (11.9 kB) .xls (18.4 kB)The vast majority of the decline in net FDI earnings within the industrial grouping came from professional, scientific & technical, where credits fell from £11.5 billion to £8.5 billion between 2011 and 2014, while debits rose by £0.3 billion – together negatively contributing £3.3 billion to the fall in net earnings. Administrative & support also negatively contributed £1.0 billion to the fall in net earnings; mainly driven by a fall in credits.

Financial & insurance was the only sub-industry where net FDI earnings improved; due to a larger decrease in the value of UK debits compared to credits within the industry between 2011 and 2014.

Notes for FDI by economic activity

Industry analysis, based on an earlier vintage of data, is available here.

Note that decreases in credits and increases in debits are negative, and vice versa.

Referred to as Section J within SIC 2007.

Referred to as Section H within SIC 2007.

Referred to as Section G within SIC 2007.

Referred to as Section I within SIC 2007.

Financial & insurance include reinsurance and pension funding activities.