1. Key figures

Net long-term migration to the UK was estimated to be 298,000 in the year ending September 2014, a statistically significant increase from 210,000 in the previous 12 months, but below the peak of 320,000 in the year ending June 2005

624,000 people immigrated to the UK in the year ending September 2014, a statistically significant increase from 530,000 in the previous 12 months. There were statistically significant increases for immigration of non-EU citizens (up 49,000 to 292,000) and EU (non-British) citizens (up 43,000 to 251,000). Immigration of British citizens increased by 4,000 to 82,000, but this change was not statistically significant

An estimated 327,000 people emigrated from the UK in the year ending September 2014. Overall emigration levels have been relatively stable since 2010

271,000 people immigrated for work in the year ending September 2014, a statistically significant increase of 54,000 compared with a year earlier. This continues the rise since the year ending June 2012. The increase over the past year applied to both non-EU and EU (non-British) citizens, as well as British citizens. However, only the increase for non-EU citizens was statistically significant

Latest employment statistics show estimated employment of EU nationals (excluding British) living in the UK was 269,000 higher in October to December 2014 compared with a year earlier. Over the same period, British nationals in employment also increased (by 375,000) while non-EU nationals in employment fell by 29,000

In the year ending September 2014, work-related visas granted (main applicants) rose 8,833 (or 8%) to 115,680, largely reflecting a 6,142 (or 14%) increase for skilled work

National Insurance number (NINo) registrations to adult overseas nationals increased by 24% to 768,000 in the year ending December 2014, when compared with the previous year

37,000 Romanian and Bulgarian (EU2) citizens immigrated to the UK in the year ending September 2014, a statistically significant increase from 24,000 in the previous 12 months. Of these, 27,000 were coming for work, a rise of 10,000 on year ending September 2013, but this increase itself was not statistically significant

Immigration for study increased from 175,000 to 192,000 in the year ending September 2014, but this change was not statistically significant. Over the same period, visa applications to study at a UK university (main applicants) rose 2% to 171,065

The number of immigrants arriving to accompany or join others showed a statistically significant increase, from 66,000 to 90,000 in the year ending September 2014

There were 24,914 asylum applications (main applicants) in 2014, an increase of 6% compared with 23,584 in 2013, but low relative to the peak of 84,132 in 2002. The largest number of asylum applications in 2014 came from Eritrea (3,239), Pakistan (2,711), Syria (2,081) and Iran (2,011)

2. Overview

The Migration Statistics Quarterly Report (MSQR) is a summary of the quarterly releases of official international migration statistics. This edition covers those released on 26 February 2015 and it also includes links to other migration products released on that date. The majority of figures presented are for the year ending September 2014, but where available, figures are provided for the year ending December 2014.

Long-term migration estimates relate to people who move from their country of previous residence for a period of at least a year. Figures relating to visas include long-term and short-term migrants and their dependants; National Insurance number allocations to adult overseas nationals also include long-term and short-term migrants.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Introduction

This edition of the Migration Statistics Quarterly Report (MSQR) includes provisional estimates of international migration for the year ending September 2014.

The MSQR series brings together statistics on migration published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the Home Office and the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). Migration statistics are a fundamental component of ONS’s mid-year population estimates. These are used by central and local government and the health sector for planning and monitoring service delivery, resource allocation and managing the economy. There is considerable interest in migration statistics both nationally and internationally, particularly in relation to the impact of migration on society and on the economy. Additionally, migration statistics are used to monitor the impact of immigration policy and performance against a stated target to reduce annual net migration to the tens of thousands by 20151.

For further information on how ONS migration statistics are used, along with information on their fitness for purpose, please see the ‘Quality and Methodology Information for Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) Releases’ (217.6 Kb Pdf) . For information on the accuracy of these statistics, the difference between provisional and final figures and guidance on comparing different data sources, please see the ‘MSQR Information for Users’ (365.1 Kb Pdf). If you are new to migration statistics, you might find it helpful to read our ‘International Migration Statistics First Time User Guide’ (315.4 Kb Pdf).

New for this release:

- New tables and charts have been added to the ‘Provisional Estimates of Long-Term International Migration’ spreadsheet showing estimates of citizenship by main reason for migration and by previous main reason for migration, using the new country groupings which ONS consulted on in 2014. A list of which countries are in each of the old and new groups (371.5 Kb Excel sheet) is also available.

Accuracy of migration estimates

Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) estimates are about 90% based on data from the International Passenger Survey (IPS), with adjustments made for asylum seekers, non-asylum enforced removals, visitor and migrant switchers and flows to and from Northern Ireland.

Surveys gather information from a sample of people from a population. In the case of the IPS, the population is passengers travelling through the main entry and exit points from the UK including airports, seaports and the Channel Tunnel. The estimates produced are based on only one of a number of possible samples that could have been drawn at a given point in time. Each of these possible samples would produce an estimated number of migrants. These may be different to the true value that would have been obtained if it were possible to ask everyone passing through about their migration intentions. This is known as sampling variability.

The published estimate is based upon the single sample that was taken and is the best estimate of the true value based on the data collected. However, to account for sampling variability, the estimates are published alongside a 95% confidence interval.

The confidence interval can be interpreted as the range within which there is a high probability (95%) that the true value for the population lies because, if we were to repeat the sampling process, we would expect the true value to lie outside the confidence interval only 1 in 20 times.

The confidence interval is a measure of the uncertainty around the estimate. Confidence intervals become larger for more detailed estimates (such as citizenship by reason for migrating). This is because the number of people in the sample who have these specific characteristics (for example, EU8 citizens arriving to study in the UK) is smaller than the number of people sampled within a category at a higher level (such as the total number of EU citizens arriving to study in the UK). The larger the confidence interval, the less precise is the estimate. Therefore users of migration statistics are advised to use the highest level breakdown of data where possible.

Estimates from the IPS may change from one period to the next simply due to sampling variability. In other words, the change may be due to which individuals were selected to answer the survey, and may not represent any real-world change in migration patterns.

Statistical tests can be used to determine whether any increases or decreases that we see in the estimates from the IPS could be due to chance, or whether they are likely to represent a real change in migration patterns. If the tests show that the changes are unlikely to have occurred through chance alone, and are likely to reflect a real change, then the change is described as being statistically significant. The usual standard is to carry out these tests at the 5% level of statistical significance. This means that we would expect only 1 out of 20 differences identified as statistically significant to have occurred purely by chance.

Revisions to net migration estimates in light of the 2011 Census

In April 2014, ONS published a report (1.04 Mb Pdf) examining the quality of international migration statistics between 2001 and 2011 (1.04 Mb Pdf) , using the results of the 2011 Census. A key finding of the report was that over the ten year period annual net migration estimates were a total of 346,000 lower than total net migration implied by the 2011 Census. However, the report also showed that the quality of international migration estimates improved following changes made to the International Passenger Survey (IPS) in 2009.

Within the report, ONS published a revised series of net migration estimates for the UK. Published tables have been updated on the ONS website to include the revised estimates. The report (1.04 Mb Pdf), a summary and guidance (55.9 Kb Pdf) on how to use these revised figures are available on the ONS website.

Note on use of LTIM and IPS in the MSQR

The MSQR uses LTIM estimates where available. However, for some combinations of variables it is not possible to aggregate IPS survey data up to full LTIM statistics. In such cases the IPS statistics are presented, which exclude the various adjustments used to create LTIM: asylum seekers, non-asylum enforced removals, visitor and migrant switchers and flows to and from Northern Ireland. This means that the IPS totals will not match LTIM totals, but will still give a good measure of magnitude and direction of change. In the main body of the report (Section 1 onwards) any IPS statistics are indicated as such.

Notes for introduction

There have been references to the target in documents and speeches. For example:

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/jcb-staffordshire-prime-ministers-speech

4. Net migration to the UK

This section describes the latest international migration statistics within the context of the historical time series of the statistics and sets out the likely drivers behind the trends observed.

Net migration is the difference between immigration and emigration. The net migration estimate for the year ending September 2014 is 298,000 and has a confidence interval of +/-43,000. This is a statistically significant increase from the estimate of 210,000 (+/-36,000) in the previous year. This continues the generally increasing trend in net migration over the last two years since the recent low of 154,000 in the year ending September 2012.

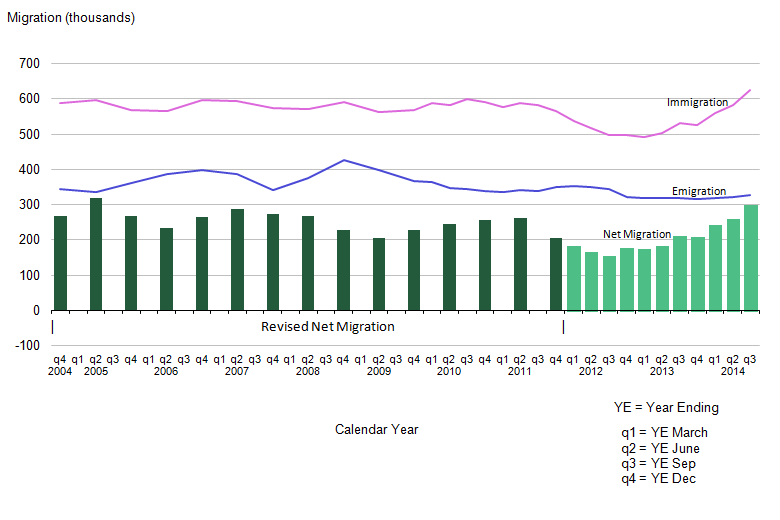

Figure 1.1a shows rolling annual estimates from the year ending December 2004 onwards. This shows that net migration remains lower than the peak of 320,000 in the year ending June 2005. Figure 1.1b provides annual totals from 1970 to 2013 to show the longer-term context.

Figure 1.1a: Long-Term International Migration, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: Long-term International Migration - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures for quarters ending in 2014 are provisional.

- Net migration estimates up to 2011 have been revised in light of the 2011 Census. Therefore they will not be consistent with the separate immigration and emigration figures shown. The revised estimates are only available for the years ending June and December each year.

Download this image Figure 1.1a: Long-Term International Migration, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

.png (22.4 kB) .xls (36.4 kB)

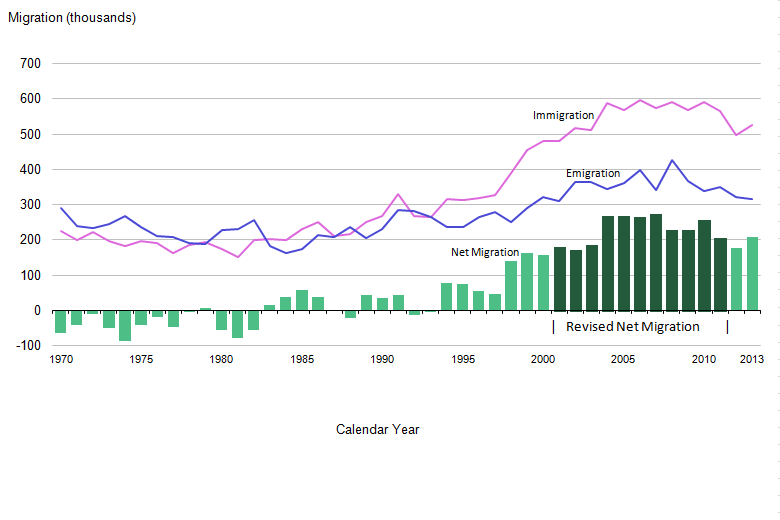

Figure 1.1b: Long-Term International Migration, 1970 to 2013 (annual totals)

Source: Long-term International Migration - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Net migration estimates for the period 2001 to 2011 have been revised in light of the 2011 Census. Therefore they will not be consistent with the separate immigration and emigration figures shown.

Download this image Figure 1.1b: Long-Term International Migration, 1970 to 2013 (annual totals)

.png (23.0 kB) .xls (32.3 kB)During the 1960s and 1970s, there were more people emigrating from the UK than arriving to live in the UK. During the 1980s and early 1990s, net migration remained at a relatively low level. Since 1994, it has been positive every year and rose sharply after 1997. During the 2000s, net migration increased, in part as a result of immigration of citizens from the countries that joined the EU in 2004. Since the mid-2000s, annual net migration has fluctuated between around 150,000 and 300,000.

The most recent increases in net migration have been driven by higher levels of immigration coupled with stable levels of emigration. Table 1 shows that there was a statistically significant increase in immigration to 624,000 (+/-36,000) in the year ending September 2014, from 530,000 (+/- 30,000) in the year ending September 2013. The latest immigration figure is the highest in the series, but users should be aware that no revisions were made to immigration and emigration estimates at the time the net migration estimates were revised.

Emigration was estimated to be 327,000 (+/- 23,000) in the year ending September 2014, similar to the figure of 320,000 a year earlier.

Table 1 shows the key figures for the year ending September 2014 and the previous year with their corresponding confidence intervals. The annual differences are also presented with the confidence interval for these differences.

Table 1: Latest changes in migration

| United Kingdom | ||||||

| Thousands | ||||||

| YE Sep 2013 | 95% CI | YE Sep 2014 | 95% CI | Difference | 95% CI | |

| Net Migration | 210 | +/-36 | 298 | +/-43 | 88 | +/- 56 |

| Immigration | 530 | +/-30 | 624 | +/-36 | 95 | +/- 47 |

| Emigration | 320 | +/-19 | 327 | +/-23 | 7 | +/- 30 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||

| Notes: | ||||||

| 1. Figures are rounded to the nearest thousand. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | ||||||

| 2. Further information on confidence intervals can be found in the MSQR Information for Users. | ||||||

| 3. The difference has been calculated by subtracting the 2013 estimate from the 2014 estimate. Where the confidence interval for the difference does not contain zero, we can say that the difference is statistically significant. This means that the difference is likely to reflect a real change in migration flows. There are statistically significant differences for immigration and net migration but not for emigration. | ||||||

| 4. YE = Year Ending. | ||||||

| 5. CI = Confidence Interval. | ||||||

Download this table Table 1: Latest changes in migration

.xls (27.6 kB)In December 2013, ONS published a report on the history of immigration to the UK based on the 2011 Census, which provides further evidence of the drivers behind historical migration to the UK.

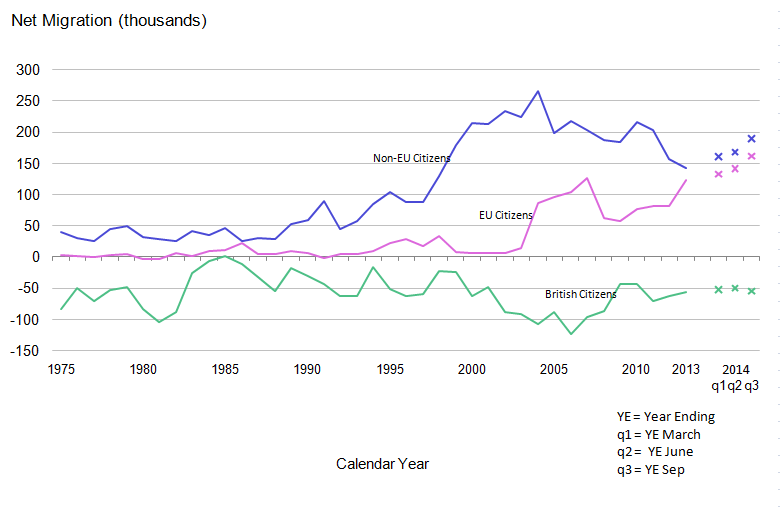

Figure 1.2 shows trends in net migration for EU, non-EU and British citizens.

The latest estimates show an increase in EU net migration, to 162,000 in the year ending September 2014 from 130,000 in the previous year, but this change was not statistically significant. Until the year ending December 2013 there had been a decline in the net migration of non-EU citizens; however, the estimates for year ending September 2014 show a statistically significant increase from the previous year, from 138,000 to 190,000. This is driven by a statistically significant increase in net migration for Commonwealth citizens, from 47,000 to 82,000 in the year ending September 2014. Overall, non-EU net migration is at its highest level since the year ending December 2011 (Figure 1.2).

Net migration of British citizens is negative, reflecting higher emigration than immigration for this group. This has remained relatively stable over the last few years, and was estimated to be 55,000 in the year ending September 2014. The largest value of net emigration was -124,000 in the year ending December 2006.

Figure 1.2: Long-Term International Net Migration by citizenship, 1975 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: Long-term International Migration - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures for 2014 are provisional. All other figures are final calendar year estimates of LTIM. Provisional rolling quarterly estimates are denoted by a cross.

- This chart is not consistent with the total revised net migration estimates as shown in Figure 1.1. Please see guidance on revised net migration statistics for further information.

Download this image Figure 1.2: Long-Term International Net Migration by citizenship, 1975 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

.png (28.4 kB) .xls (35.8 kB)Using the new country groupings which ONS consulted on in 2014, the latest IPS estimates show that there was a statistically significant increase in net migration of South Asian citizens, but a statistically significant decrease in net migration of East Asian citizens. South Asian estimates doubled from 24,000 to 48,000 and East Asian estimates declined from 43,000 to 24,000 between the year ending September 2013 and the year ending September 2014.

A listing of which countries are in each of the old and new groups (371.5 Kb Excel sheet) is available.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Immigration to the UK

In Section 1, we looked at net migration, the difference between immigration and emigration. In this section, we look at the immigration component in more detail.

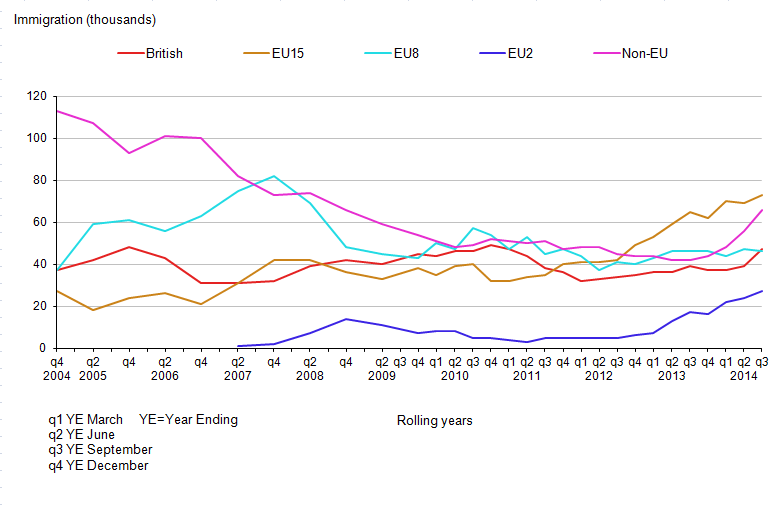

The latest immigration estimate for the year ending September 2014 is 624,000, with a confidence interval of +/-36,000. There has been a statistically significant increase in immigration from 530,000 (+/-30,000) in the previous year. The latest immigration figure of 624,000 is the highest in the series but users should be aware that no revisions were made to immigration and emigration estimates at the time the net migration estimates were revised.

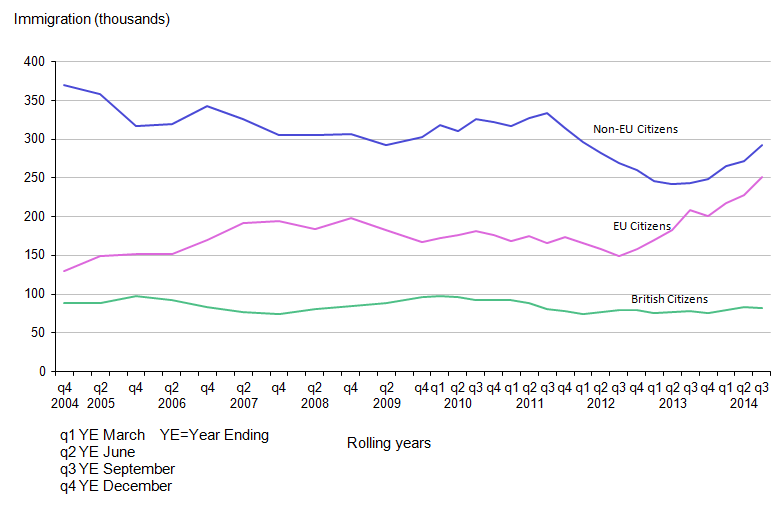

There has been a statistically significant increase among both EU and non-EU citizens (Figure 2.1). Immigration of EU citizens has increased to 251,000 in the year ending September 2014, from 208,000 in the year ending September 2013. Non-EU immigration increased to 292,000 in the year ending September 2014, from 243,000 in the previous 12 months. While the increase in EU immigration continues the recent trend, immigration of non-EU citizens had declined from 2011 to 2013, before the recent increase (Figure 2.1).

The varying trends in migration patterns among EU and non-EU citizens reflect their different rights to immigrate to the UK and the impact of government policy.

Figure 2.1: Immigration to the UK by citizenship, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: Long-term International Migration - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures for 2014 are provisional.

- This chart is not consistent with the total revised net migration estimates as shown in Figure 1.1. Please see guidance on revised net migration statistics for further information.

Download this image Figure 2.1: Immigration to the UK by citizenship, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

.png (23.0 kB) .xls (35.3 kB)British citizens

Long-Term International Migration estimates by citizenship show that, in the year ending September 2014, the estimated number of British citizens immigrating to the UK was 82,000. This figure is similar to the 78,000 British citizens estimated to have immigrated to the UK in the previous year. IPS estimates show that the majority of British citizens are immigrating for work-related reasons (47,000). The next most common reason is ‘going home to live’ (14,000), followed by accompanying/joining others (10,000) and formal study (6,000). Generally, immigration of British citizens remains relatively stable, both in terms of the overall level and the main reasons for immigrating.

EU citizens

Immigration of EU citizens (excluding British) was estimated to be 251,000 in the year ending September 2014, a statistically significant increase from 208,000 in the previous year and the highest recorded level for this group (Figure 2.1).

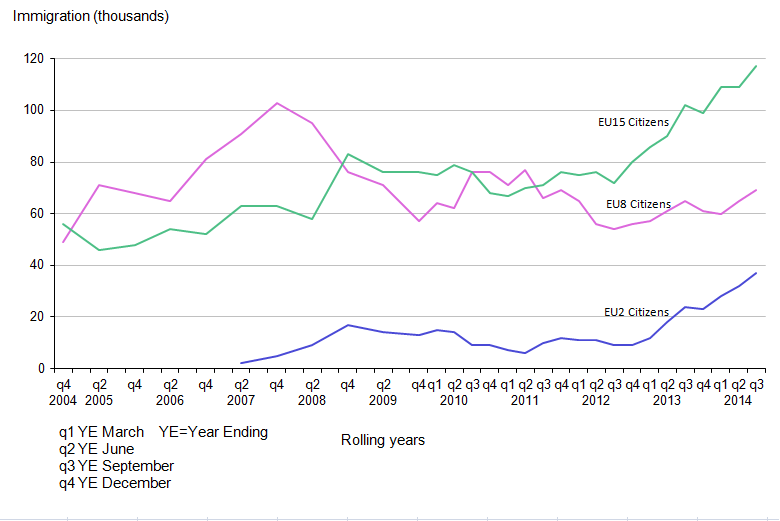

Figure 2.2 shows estimates for specific groups of EU countries, namely the first 15 EU member states (EU15), the 8 Central and Eastern European countries that joined in 2004 (EU8) and Bulgaria and Romania (EU2), which joined in 2007. IPS estimates show that 51%, 30% and 16% of total EU immigration in the year ending September 2014 was accounted for by citizens of the EU15, EU8 and EU2 respectively.

Figure 2.2: EU Immigration to the UK, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: International Passenger Survey (IPS) - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures for 2014 are provisional.

Download this image Figure 2.2: EU Immigration to the UK, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

.png (26.9 kB) .xls (35.8 kB)EU15 citizens

The recent increase in EU immigration has been partly driven by an increase, albeit not statistically significant, in the number of EU15 citizens (excluding British) arriving in the UK, from 107,000 in the year ending September 2013 to 128,000 in the year ending September 2014 (LTIM figures).

IPS estimates show that the most common reason for immigration among EU15 citizens is work, with 73,000 (62%) arriving for this reason in the year ending September 2014, a slight but not statistically significant increase from 65,000 in the previous year.

EU8 citizens

Over the last five years, immigration of EU8 citizens has been relatively stable. An estimated 78,000 EU8 citizens (LTIM figures) immigrated to the UK in the year ending September 2014, compared with 73,000 in the previous year. These levels are lower than the 112,000 EU8 citizens who immigrated in the year ending December 2007. IPS estimates show that, in the year ending September 2014, the majority (67%) of EU8 citizens arrived for work-related reasons (46,000).

It should be noted that in May 2011, transitional controls that applied to EU8 citizens seeking work in other EU countries expired (these were never applied in the Irish Republic, Sweden and the UK). This may have had the effect of diverting some EU8 migration flows to other EU countries, such as Germany, which in 2013 experienced its highest level of net migration since 1993.

EU2 citizens

The latest IPS estimates for the year ending September 2014 show that an estimated 37,000 Bulgarian and Romanian (EU2) citizens migrated to the UK. This was a statistically significant increase from 24,000 in the previous year. An estimated 73% of EU2 citizens arrived for work-related reasons (27,000), compared with 71% (17,000) in the year ending September 2013.

Bulgaria and Romania joined the European Union (EU) on 1 January 2007. Migrants from these countries coming to the UK were initially subject to transitional employment restrictions, which placed limits on the kind of employment they could undertake. These restrictions ended on 1 January 2014.

Non-EU citizens

Immigration of non-EU citizens increased to 292,000 in the year ending September 2014, from 243,000 in the previous year. This was a statistically significant increase and is the highest estimate since the year ending March 2012 (Figure 2.1).

In the year ending September 2014, there was a statistically significant increase in immigration for the Other Foreign citizenship group, to 165,000 from 141,000 in the year ending September 2013. IPS estimates show that the majority of these Other Foreign citizens arrive for formal study (89,000) and the numbers arriving for study have been stable for some time. The increase in immigration among this citizenship group appears to be driven by statistically significant rises in Other Foreign citizens arriving for work-related reasons (24,000 compared with 15,000 in the previous year) and accompanying/joining others (28,000 compared with 18,000 in the previous year).

The longer-term decline in immigration of non-EU citizens has been largely due to lower immigration of New Commonwealth citizens, in particular for study. These changes are likely to be related to changes also seen in the visa statistics, reflecting the sharp decline in sponsored study applications in the further education sector (see Section 2.3).

The latest IPS estimates using the new country groupings which ONS consulted on in 2014 show that there was a statistically significant increase in immigration of citizens from many of the country groups, including South Asia, which increased from 48,000 to 65,000 between the year ending September 2013 and the year ending September 2014.

Administrative data on entry clearance visas provide information on the nationality of those who are coming to the UK, though they only relate to those nationals subject to immigration control. The majority of people subject to immigration control are nationals of non-EU countries.

Figure 2.3: Entry clearance visas granted (excluding visitor and transit visas), by world area, UK, 2005 to 2014

Source: Home Office

Notes:

- A small number (one to two thousand per year excluding visitor and transit visas) of Home Office visas cannot be ascribed to a world area and are categorised as ‘Other’. This category does not appear in the above chart.

- European Economic Area (EEA) nationals do not require a visa to enter the UK, however see p 34 of User Guide to Home Office Immigration Statistics for exceptions (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/user-guide-to-home-office-immigration-statistics--9)

- See the Glossary for discussion of world regions and differences between Home Office and DWP definitions.

Download this chart Figure 2.3: Entry clearance visas granted (excluding visitor and transit visas), by world area, UK, 2005 to 2014

Image .csv .xlsFigure 2.3 shows trends in visas granted (excluding visitor and transit visas) by world area since 2005. From the year ending September 2009 onwards, those with an Asian nationality have accounted for the majority of visas and have driven the recent fluctuations in visa numbers. Asian nationals accounted for 294,697 (54%) of the 546,371 visas granted in the year ending December 2014, with India and China each accounting for 16% of the total.

The number of visas granted in the year ending December 2014, excluding visitor and transit visas, was 14,321 higher than in the year ending December 2013 (532,050). This included increases for India (up 6,542 or +8%), China (up 4,044 or +5%) and Libya (up 2,262 or +36%).

Although the above figures exclude visitor and transit visas, they will include some individuals who do not plan to move to the UK for a year or more as well as dependants. There is evidence that recent increases in visas granted have reflected higher numbers of short-term visas. The Home Office short story indicated that the increase from 2012 to 2013 in total visas granted, excluding visit and transit visas, was accounted for by higher numbers of short-term (less than 1 year) visas. Nevertheless, recent trends in visas granted have provided a good leading indicator for trends in long-term non-EU immigration.

For more information see the Home Office Immigration Statistics, October to December 2014 bulletin. In addition, ONS will be publishing its next annual report on Short-Term International Migration on 21 May 2015.

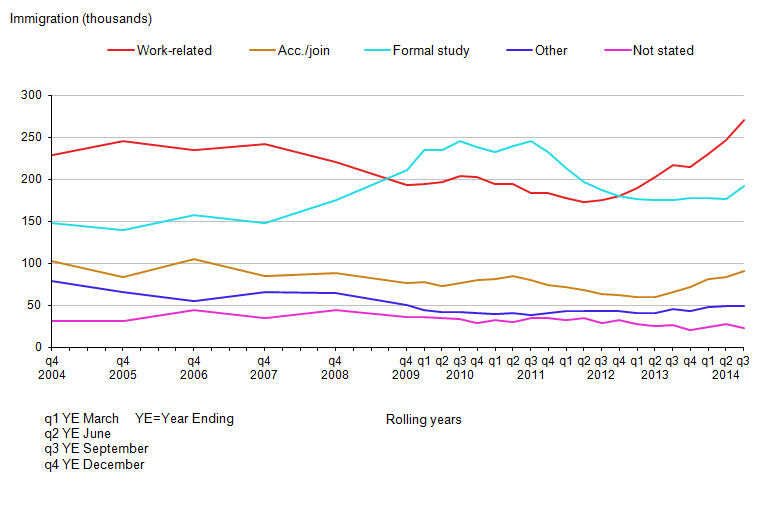

2.1 Immigration to the UK by main reason

The next sections describe the main reason for migration for long-term immigrants to the UK. Three-quarters of immigrants to the UK are people migrating to work or study (Figure 2.4). Changes in flows of people migrating for these reasons are affected by the differing rights of EU and non-EU citizens to migrate to the UK and by the impact of government policy.

Home Office visa statistics show that most of the 546,371 visas granted (excluding visitors and transit visas) to non-EEA nationals in the year ending December 2014 were for study (220,116, excluding student visitors) or for work (167,202). In addition, 73,625 student visitor and 34,967 family-related visas were granted.

IPS long-term immigration estimates for work and formal study broadly follow the same trends as visas granted for work and study. However, IPS estimates tend to be lower than the visa figures. A key reason for this is that IPS estimates exclude those individuals who intend to stay for less than 1 year. There has been analysis showing that, in recent years, the number of visas for less than 12 months duration has increased, while the number of longer-term visas have fallen.

Furthermore, the dependants of those granted a visa to work or study are included in the work and study visas figures, whereas the reason for migration for such individuals would be recorded as accompanying/joining others on the IPS.

IPS statistics and visa statistics represent flows of people, only a proportion of whom will remain for longer periods. A recent Home Office research report ‘The reason for migration and labour market characteristics of UK residents born abroad’ (September 2014) uses ONS data from the Labour Force Survey to provide estimates of the number of residents born abroad by the reason for original migration.

A key finding of this was that the distribution of original purposes given for migrating by people resident in the UK who were born abroad is different from that produced when looking at the migration flows reported in the IPS. For example, the proportion of people who come for family purposes or as a dependant takes greater significance, because of the higher likelihood of people who come for relationship reasons to stay longer. Similarly, although many foreign students are temporary, the analysis confirmed findings in other studies that a number of foreign students do stay on as residents.

Figure 2.4: Long-Term International Migration estimates of immigration to the UK, by main reason for migration, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: ong-term International Migration - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures for 2014 are provisional.

- Up to year ending December 2009, estimates are only available annually.

- Acc./join means accompanying or joining.

Download this image Figure 2.4: Long-Term International Migration estimates of immigration to the UK, by main reason for migration, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

.png (26.2 kB) .xls (33.3 kB)2.2 Immigration for work

The most commonly stated reason for immigration to the UK is work (Figure 2.4). This has been the case historically, with the exception of 2009 to 2012, when study was the most common main reason for immigration.

The majority of sources show that immigration for work has increased over the last year for both EU and non-EU citizens. Data from the IPS, LFS and National Insurance number (NINo) registrations suggest that there has been an increase in immigration for work among EU citizens. The IPS and NINo data suggest that this increase applied to both EU15 and EU2 citizens. The LFS, which includes short-term migrants and changes in employment in the resident population, also suggests that there has been an increase in EU8 citizens in employment.

There has also been an increase in the number of non-EU citizens who have immigrated for work-related reasons. The number of non-EU immigrants for work-related reasons rose by 24,000 to 66,000 according to the latest IPS figures. 80% of non-EU immigrants who arrived for work-related reasons had a job to go to. This is consistent with the increase in visas issued to non-EU citizens. These visas were predominantly issued to skilled workers. Figures for the Labour Force Survey and NINo registrations, which include both short-term and long-term migrants, both showed falls in the number of non-EU workers.

More information on individual sources is as follows:

LTIM estimates show that, in the year ending September 2014, a total of 271,000 people migrated to the UK for work-related reasons. This is a statistically significant increase from 217,000 in the previous year and is the highest figure in the series, although users should be aware that no revisions were made to estimates by reason for migration at the time the overall net migration estimates were revised

this increase includes a statistically significant rise in immigration of non-EU citizens for work, but also an increase of immigration of EU citizens for work which is not statistically significant. These statistics are covered in more detail later in this section

Labour market statistics from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) show that the number of non-UK nationals in employment increased by 239,000 (or 9%) to 3.0 million in October to December 2014 compared with the same quarter in the previous year (2.7 million). Employment of EU nationals increased by 269,000 (17%) to 1.8 million, while employment of non-EU nationals decreased by 29,000 (3%) to 1.1 million. The growth in overall employment over the last year was 611,000, and of this 61% can be accounted for by a growth in employment for UK nationals

in 2014, there were 8% more work-related visas granted (up 12,442 to 167,202), largely accounted for by 13% higher skilled work grants (+10,743) and 87% higher grants of investor visas (+1,397). Over the same period there was a corresponding 14% increase in sponsored visa applications for skilled work (54,571 in 2014, main applicants). Most of the applications were for the Information and Communication (23,151), Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities (10,439), and Financial and Insurance Activities (6,529) sectors. 56% of the sponsored skilled workers were Indian nationals and a further 12% were USA nationals

in the year ending December 2014, the number of new National Insurance numbers (NINos) allocated to non-UK nationals was 768,000 (Figure 2.6), an increase of 151,000 (24%) on the previous 12 months

It is important to note that these different data sources are not directly comparable with each other. More information on this is available in the MSQR Information for Users (365.1 Kb Pdf) .

Figure 2.5: Immigration to the UK for work-related reasons by citizenship, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: International Passenger Survey (IPS) - Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 2.5: Immigration to the UK for work-related reasons by citizenship, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

.png (28.9 kB) .xls (33.8 kB)The latest IPS estimates show that around 57% of immigrants arriving for work were EU citizens, 25% were non-EU citizens and a further 18% were British citizens.

EU immigration for work began to increase following the EU Accession (enlargement) in 2004, from 65,000 in 2004, to 125,000 in 2007. There was a decline in EU immigration for work during 2008, particularly among EU8 citizens, following which it remained steady at around 90,000 until 2012. In the last two years, EU immigration for work increased again. IPS estimates show that 147,000 EU citizens arrived for work in the year ending September 2014 – an increase, albeit not statistically significant, from 128,000 in the previous year. This comprised the following (none of which are statistically significant):

EU15 citizens – an increase to 73,000 from 65,000

EU8 citizens – remaining steady at 46,000

EU2 citizens – an increase to 27,000 from 17,000

Approximately 58% of all EU immigrants arriving for work-related reasons had a definite job to go to. The equivalent percentages for the EU15, EU8 and EU2 citizenship groups are 67%, 52% and 41% respectively.

In 2004, 113,000 non-EU citizens arrived for work with an intention to remain more than 12 months. This figure declined until 2013, but the latest estimates show that there has been a statistically significant increase in non-EU immigration for work to 66,000 in the year ending September 2014, up from 42,000 in the previous year (Figure 2.5).

Using the new country groupings which ONS consulted on in 2014, the latest IPS estimates show that there were statistically significant increases in migrants coming to the UK for work-related reasons from both South and East Asia. South Asian citizens arriving for work-related reasons increased from 10,000 to 22,000 between the year ending September 2013 and the year ending September 2014. The majority (91%) had a definite job to go to. Citizens of East Asia (including China) coming for work increased from 3,000 to 7,000 between the year ending September 2013 and the year ending September 2014.

National Insurance number (NINo) allocations to overseas nationals

The number of NINos registered to non-UK nationals shows a peak of 797,000 in 2007 following a steady increase since 2004. For several years they fluctuated around 600,000, falling to a low of 519,000 in 2012. However, latest data show a recent increase to 768,000 registrations in the year ending December 2014 (Figure 2.6). It should be noted that these figures also include short-term migrants and are not a direct measure of when a person immigrated to the UK, as those registering may have arrived to live in the UK weeks, months or years before registering – and may have subsequently returned abroad.

National Insurance number (NINo) allocations to overseas nationals

The number of NINos registered to non-UK nationals shows a peak of 797,000 in 2007 following a steady increase since 2004. For several years they fluctuated around 600,000, falling to a low of 519,000 in 2012. However, latest data show a recent increase to 768,000 registrations in the year ending December 2014 (Figure 2.6). It should be noted that these figures also include short-term migrants and are not a direct measure of when a person immigrated to the UK, as those registering may have arrived to live in the UK weeks, months or years before registering – and may have subsequently returned abroad.

Figure 2.6: National Insurance number allocations to adult overseas nationals by world area of origin, UK, 2005 to 2014

Source: Department for Work and Pensions

Notes:

- EU Accession countries here refers to the EU8, the EU2, Cyprus, Malta and Croatia (see Glossary). This definition applies to the full time series.

- The figures are based on the recorded registration date on the National Insurance Recording and Pay as you Earn System (NPS), ie after the NINo application process has been completed. This may be a number of weeks or months (and in some cases years) after arriving in the UK.

Download this chart Figure 2.6: National Insurance number allocations to adult overseas nationals by world area of origin, UK, 2005 to 2014

Image .csv .xls

Table 2: National Insurance number registrations to adult overseas nationals entering the UK - Year Ending December 2014

| United Kingdom | ||||

| Thousands | ||||

| World area | Year to December 2013 total | Year to December 2014 total | Difference | % Change to previous year |

| Total | 617.2 | 767.8 | 150.5 | 24% |

| European Union | 440.0 | 590.5 | 150.5 | 34% |

| Non European Union | 176.7 | 175.6 | -1.1 | -1% |

| EU15 | 207.6 | 217.1 | 9.5 | 5% |

| EU8 | 201.6 | 182.6 | -19.1 | -9% |

| EU2 | 27.7 | 187.4 | 159.7 | 576% |

| Source: Department for Work and Pensions | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. The figures are based on recorded registration date on the National Insurance Recording and Pay as you Earn System, i.e. after the NINo application process has been completed. This may be a number of weeks or months (and in some cases years) after arriving in the UK. | ||||

| 2. The data series include both short-term and long-term migrants. | ||||

| 3. The number of new registrations of NINos to non-UK nationals over a given period is not the same as the total number of non-UK nationals who hold a NINo. | ||||

| 4. The total number of non-UK nationals who have been allocated a NINo is not the same as the number of non-UK nationals working in the UK. This is because people who have been allocated NINos may subsequently have left the UK, or they may still be in the UK but have ceased to be in employment. | ||||

| 5. Some people arriving into the UK may already hold a NINo from a previous stay in the UK. Once a person has been allocated a NINo, they do not need to reapply in order to work in the UK. | ||||

Download this table Table 2: National Insurance number registrations to adult overseas nationals entering the UK - Year Ending December 2014

.xls (28.2 kB)Increases in immigration for work among EU15 and EU2 citizens are reflected in data on NINo registrations to adult overseas nationals (Table 2) from within the EU. For EU15 citizens the number of NINo registrations in 2014 was 591,000, an increase of 150,000 (34%) on 2013. Romanian (146,000), Polish (107,000), Italian (51,000), Spanish (50,000), and Bulgarian (42,000) form the top 5 EU nationalities for NINo registrations in 2014. One-third of EU2 NINo registrations in 2014 were to Romanians and Bulgarians who arrived in the UK prior to 1 January 2014.

For non-EU citizens, the number of NINo registrations in 2014 was 176,000, a fall of 1,000 (1%) on 2013. Indian (32,000), Pakistani (13,000), Chinese (13,000), Australian (11,000) and Nigerian (11,000) form the top 5 non-EU nationalities for NINo registrations in 2014.

Labour market statistics

The latest labour market statistics from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) show that the number of non-UK nationals in employment increased by 239,000 (9%) to 3.0 million in October to December 2014 compared with the same quarter in the previous year (2.7 million). Employment of EU nationals increased by 269,000 (17%) to 1.8 million, while employment of non-EU nationals decreased by 29,000 (3%) to 1.1 million. The growth in overall employment over the last year was 611,000 and, of this, 61% can be accounted for by a growth in employment for UK nationals.

Labour market statistics show an estimated 154,000 EU2 citizens were employed in the UK in October to December 2014, an increase of 19% from the same quarter in the previous year. This follows the lifting of labour market restrictions for EU2 citizens in January 2014.

This compares with an increase of 11% to 761,000 for EU15 (excluding British) citizens and an increase of 23% to 895,000 for EU8 citizens. Labour market statistics are a measure of the stock of people working in the UK, rather than a measure of migration flows. Therefore, the increase in employment among EU8 citizens may be partially accounted for by those who were already resident in the UK taking up employment. There have been recent increases in the number of EU8 citizens arriving in the UK to accompany/join others and these people may subsequently take up employment in the UK. In addition, the labour market figures include both short-term and long-term migrants.

Overall, the IPS and LFS estimates and NINo allocations data all provide evidence that there has been increased immigration for work among EU citizens. IPS estimates suggest that this increase has been predominantly among EU15 and EU2 citizens. Labour market statistics are showing increased levels of employment across all EU groupings, with the greatest increases among EU2 and EU8 citizens. Note, however, that both NINo and labour market statistics will include short-term workers as well as long-term migrants.

Work-related visas (Non-EEA nationals)

There have previously been falls in work-related visas granted following the introduction of the Points Based System and more recently related to the closure of the Tier 1 General and Tier 1 Post-Study categories to new applicants – see Home Office Work topic. These trends also reflect the changing economic environment over that period. More recently, the numbers of skilled work visas (Tier 2) have started to rise.

In 2014, there were 8% more work-related visas granted (up 12,442 to 167,202), largely accounted for by higher numbers of skilled work visas (+10,743) and higher numbers of investor visas (+1,397). Over the same period, there was also a corresponding 14% increase in sponsored visa applications for skilled work (to 54,571 in 2014, main applicants). Most of the applications were for the Information and Communication (23,151), Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities (10,439), and Financial and Insurance Activities (6,529) sectors (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7: Skilled work visa applications by industry sector, 2010 to 2014

Source: Home Office

Notes:

- As part of the application process for visas, individuals must obtain a certificate of sponsorship from an employer. The data shown relate to the numbers of sponsoring documents used by main applicants applying for Tier 2 (Skilled work) visas

- European Economic Area (EEA) nationals do not require a visa to enter the UK

Download this chart Figure 2.7: Skilled work visa applications by industry sector, 2010 to 2014

Image .csv .xlsWork-related grants for extensions to stay longer in the UK fell by over a quarter (-33,907, or -28%) to 88,551 in 2014. This included falls in Tier 1 General (-32,055) and Tier 1 Post Study (-816), both categories closed to new entrants, as well as for Tier 2 skilled workers (-2,194), and domestic workers (-1,235). These were partly offset by increases for Tier 1 Entrepreneurs (+2,278) and Tier 1 Investors (+377).

The Migrant Journey Fifth Report indicated that, based on data matching, over a quarter (28%) of those issued skilled work visas in 2008 had either been granted permission to stay permanently (settlement) or still had valid leave to remain five years later. This was lower than the 44% of those granted skilled work visas in 2004.

2.3 Immigration for study

Immigration to the UK for study increased from 175,000 to 192,000 in the year ending September 2014, albeit not statistically significantly. Over the same period, visa applications to study at a UK university (main applicants) rose 2% to 171,065.

LTIM estimates show how the number of people coming to the UK to study has changed over the last ten years (Figure 2.4). The figures include all educational sectors, including universities and other forms of study. Around 150,000 long-term migrants arrived annually to study in the middle part of the last decade. After 2007 this increased to a two-year plateau of around 240,000 in 2010 and 2011 before falling below 180,000 by 2013. However, since the year ending September 2013 the figure has risen (not statistically significantly) to 192,000. IPS estimates for the year ending September 2014 show that over 70% of long-term immigrants to the UK for study are non-EU citizens. Of these, approximately two-thirds are Asian citizens.

IPS estimates also show that the number of New Commonwealth citizens, which includes the Indian subcontinent, coming to the UK to study in the year ending September 2014 was 36,000. This is one-third of the peak of 108,000 in the year ending June 2011. Immigration for formal study from the Other Foreign citizenship group, which includes China, has been relatively stable over the last four years and was estimated to be 89,000 in the year ending September 2014. EU15 immigration for formal study was estimated to be 31,000 in the year ending September 2014. This is a return to the level seen in the year ending June 2010.

The latest IPS estimates using the new country groupings, which ONS consulted on in 2014, show that there were statistically significant increases for citizens of the Middle East and Central Asia grouping; North America, and Central and South America. Estimates for the Middle East and Central Asia grouping increased from 6,000 to 11,000 between the year ending September 2013 and the year ending September 2014. Estimates for North America also increased from 6,000 to 11,000 over the same period, while estimates for Central and South America increased from 4,000 to 12,000.

Home Office statistics show that there were 220,116 visas granted for the purposes of study (excluding student visitors) in 2014, a rise of 0.7%. There were large rises in numbers of study visas granted (excluding student visitors) for Chinese (+2,070 or +3%), Saudi Arabian (+1,084 or +12%) nationals, and falls for Indian (-999 or -7%) and Nigerian (-1,521 or -13%) nationals.

Trends in student numbers over time, as recorded by study visa applications, differ by nationality and by education sector. IPS long-term immigration estimates, while being substantially lower, follow a broadly similar trend to student visas granted, with increases in both series during 2009 and decreases after the year ending June 2011 (and with both study visas granted and IPS increasing more recently).

Statistics on sponsored applications for visas by education sector show that the falls in visas granted to non-EEA nationals for study have been in the non-university sector (Figure 2.8). The number of study-related sponsored visa applications (main applicants) overall fell 1% in 2014 (208,427) compared with 2013 (210,099). However, there was a slight rise in sponsored visa applications for the university sector (to 168,565, up 0.3%) and independent schools (to 14,035, up 3%) alongside falls in the further education sector (to 19,365, down 10%) and English language schools (to 3,351, down 5%).

Figure 2.8: Study-related sponsored visa applications by sector, 2010 to 2014

Source: Home Office

Notes:

- The numbers show the use of a Certificate of Acceptance for Study (CAS) in a study visa application.

- Universities are 'recognised bodies' (meaning that it has its own UK degree-awarding powers), or bodies in receipt of public funding as a Higher Education Institute (HEI). Institutions (including further education colleges) which receive some public funding to deliver higher education courses do not fall within this definition of an HEI. They are UK-based. Further education contains the remainder of sponsors who described themselves as ‘University and tertiary’, plus those who described themselves as ‘Private Institution of Further or Higher Education’ or whose self-description included ‘further education’ or ‘higher education’. Includes a small number of foreign-based universities, but these account for very small numbers of CAS used.

- The chart excludes sponsored visa applications from a small number of other sponsors.

Download this chart Figure 2.8: Study-related sponsored visa applications by sector, 2010 to 2014

Image .csv .xlsThe number of student visitor visas granted fell by 5% (-3,976) to 73,625, after doubling over the previous four years from 37,703 in 2009. Student visitors are normally only allowed to stay for up to six months (11 months for English language schools) and cannot extend their stay.

For more information on immigration to the UK for study, see the Home Office topic report on Study.

2.4 Immigration for other reasons

Reasons for migrating other than work or study include accompanying or joining family or friends, asylum and returning home to live.

LTIM estimates show that the third most common reason for migrating to the UK is to accompany/join others. In the year ending September 2014, 90,000 long-term migrants arrived in the UK to accompany or join others, a statistically significant increase from 66,000 in the previous year (Figure 2.4). Immigration to accompany/join others peaked at 105,000 in 2006, prior to the recent economic downturn, but then declined reaching a low of 59,000 in the year ending March 2013. Recent increases represent a return to levels similar to those in 2011. According to IPS estimates, there was a statistically significant increase in immigration of Other Foreign citizens to accompany/join others to 28,000 in the year ending September 2014, from 18,000 in the previous year.

As would be expected, the vast majority (14,000) of the 15,000 immigrants who stated ‘going home to live’ as their reason for immigrating were British.

Family visas (Non-EEA nationals)

Entry clearance visa statistics show that 34,967 family route visas were granted in 2014, an increase of 5% compared with the year ending December 2013 (33,162). However, this still stands at less than half the level of the peak in the year ending March 2007 (72,894).

The increase in IPS estimates of Other Foreign citizens arriving in the UK to accompany/join others noted above is more pronounced than the increase in family route visas granted. There are a number of possible explanations for this:

Visa figures will also include short-term migrants (people intending to stay in the UK for less than 12 months).

Dependants of those granted work or study visas will be included in the figures for those visa categories, rather than in the family visa figures; however, in the IPS these dependants may give their main reason for migration as accompany/join.

People may have multiple reasons for migrating. For example, they may hold a work visa but their main reason for migration, which they state in the IPS, is to accompany or join.

There may be a time lag between when visas are granted and when individuals travel. Individuals may be granted a visa in one quarter and then travel in a later quarter.

Also, as explained in the user guide (365.1 Kb Pdf) IPS estimates for groups with very specific characteristics (such as Other Foreign citizens arriving to accompany/join others) are based on a relatively small sample and therefore will have comparatively large confidence intervals associated with them.

These differences are subject to further research, which it is planned to report on in due course.

Further information on visas granted for family reasons has been published by the Home Office.

Asylum applications

There were 24,914 asylum applications in 2014, an increase of 6% compared with 23,584 in 2013. The number of applications remains low relative to the peak number of applications in 2002, when there were 84,132. The largest number of asylum applications in 2014 came from Eritrea (3,239), Pakistan (2,711), Syria (2,081) and Iran (2,011). Grant rates for asylum, humanitarian protection, discretionary leave or other grants of stay vary between nationalities. For example, 87% of the total decisions made for nationals of Eritrea were grants, compared with 20% for Pakistani nationals, 54% for Iranian nationals and 86% for Syrian nationals. Applications for asylum peaked in 2002 (at 84,132) but now typically account for only 4% of long-term inflows.

Further information on asylum has been published by the Home Office.

Recent Home Office publications

In February 2015, the Home Office published its ‘Migrant Journey: Fifth Report’, which shows how non-EEA migrants change their immigration status or achieve settlement in the UK.

Key results include:

20% (18,359) of those issued skilled work visas (with a potential path to settlement) in the 2008 cohort had been granted settlement five years later and a further 8% (6,912) still had valid leave to remain.

Indian nationals were issued the largest proportion (39%) of skilled work visas in the 2008 cohort and, of these skilled Indian nationals, 19% had received settlement after five years, while a further 7% still had valid leave to remain.

In May 2014 the Home Office published an update to the article ‘Extensions of stay by previous category’. Looking at extensions data by individuals’ previous category, 6,238 former students were granted extensions for work in 2013 (main applicants). The comparable figure for 2012 was 38,505. This large fall reflected the closure of the Tier 1 Post-Study category in 2012.

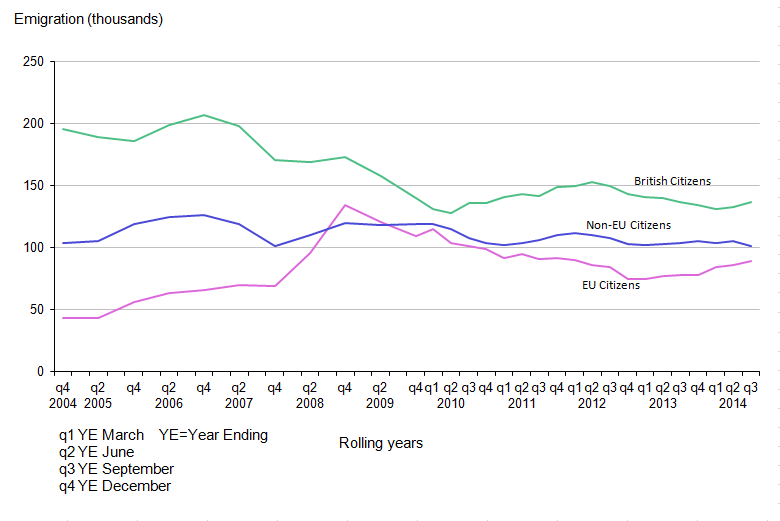

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Emigration from the UK

The latest emigration estimate for the year ending September 2014 was 327,000 with a confidence interval of +/-23,000. Recently levels of emigration have remained very stable, and well below the high of 427,000 in 2008. It is important to note that emigration comprises a range of different types of emigrant, including British citizens but also people of other citizenships, including those leaving the UK after a period of work or study.

British citizens accounted for 42% of emigrants in the year ending September 2014 (137,000). Emigration of British citizens has remained at around the same level since 2010, having fallen from the peak of 207,000 in 2006 (Figure 3.1).

The estimated number of EU citizens (excluding British) emigrating from the UK was 89,000 in the year ending September 2014, which is similar to the estimated 78,000 EU citizens who emigrated in the previous year. LTIM estimates are not available for every individual EU citizenship grouping. However, IPS estimates show that emigration among the various EU citizenship groups has been stable over the last few years, with 55% (46,000), 39% (32,000) and 5% (4,000) of EU emigration accounted for by EU15, EU8 and EU2 citizens respectively, in the year ending September 2014.

The LTIM estimates show the number of non-EU citizens emigrating from the UK in the year ending September 2014 was 101,000, a figure very similar to the previous year (104,000). While this is not a significant decrease in itself, there was a significant decrease in the number of New Commonwealth citizens emigrating, from 36,000 to 29,000 in the year ending September 2014.

Figure 3.1: Emigration from the UK by citizenship, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: Long-term International Migration - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures for 2014 are provisional.

- This chart is not consistent with the total revised net migration estimates as shown in Figure 1.1. Please see guidance note for further information.

Download this image Figure 3.1: Emigration from the UK by citizenship, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

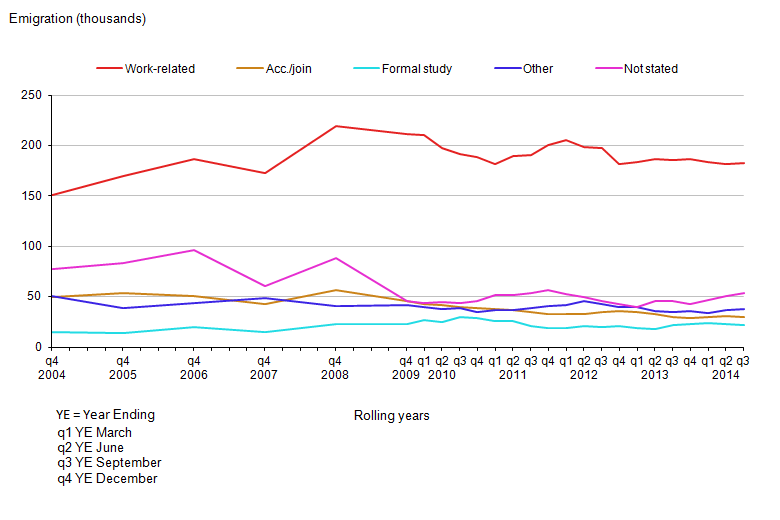

.png (23.7 kB) .xls (27.1 kB)In the LTIM estimates for the year ending September 2014, work-related reasons continue to be the main reason given for emigration and account for 56% of emigrants. An estimated 183,000 people emigrated from the UK for work-related reasons in the year ending September 2014, a similar figure to the previous year (186,000).

Of the 35,000 emigrants in the IPS who stated their main reason for migration as ‘going home to live’, 19,000 were EU citizens and 15,000 were citizens of non-EU countries. The peak of people leaving the UK to return home was in 2008, when 62,000 emigrated for this reason. This peak coincides with the start of the economic downturn.

Using the new country groupings which ONS consulted on in 2014, the latest IPS estimates show that there was a statistically significant increase in East Asian citizens leaving the UK for work-related reasons, from 13,000 in the year ending September 2013 to 18,000 in the year ending September 2014. There was also a statistically significant decrease in South Asian citizens leaving for work-related reasons between the year ending September 2013 and the year ending September 2014 (19,000 to 13,000).

Figure 3.2: Long-Term International Migration estimates of emigration from the UK, by main reason, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

Source: Long-term International Migration - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures for year ending March 2014, year ending June 2014 and year eding September 2014 are provisional.

- Up to year ending December 2009, estimates are only available annually.

- It should be noted that reasons for emigration will not necessarily match reasons for intended immigration. For example, someone arriving for study may then leave the UK after their course for work-related reasons.

- Acc./Join means accompanying or joining.

Download this image Figure 3.2: Long-Term International Migration estimates of emigration from the UK, by main reason, 2004 to 2014 (year ending September 2014)

.png (24.8 kB) .xls (25.6 kB)Home Office Research Report 68, published in November 2012, presents information from academic research and surveys drawn together to present key aspects of long-term emigration from the United Kingdom. This includes recent outward migration and some trends over the last 20 years, separately for British, EU and non-EU citizens.

The report considers where emigrants go, how long for, and their motivations. The evidence suggests emigration is mainly for work, and that the most common destinations for British citizens are Australia, Spain, the United States and France. Reasons and drivers for emigration from the UK appear to vary across citizenship groups. While many factors influence emigration, the report says that British and EU citizen emigration appears to be associated with changes in unemployment and exchange rates. This is less apparent for non-EU citizens.

3.1 People emigrating from the UK by previous main reason for immigration

In 2012 a new question was added to the IPS asking current emigrants who had previously immigrated to the UK about their main reason for migration at the time that they immigrated.

In the year ending September 2014, IPS data show that 305,000 individuals emigrated from the UK. These comprised 104,000 ‘new’ long-term emigrants (individuals who had not previously lived away from the UK for 12 months or more) and 201,000 long-term emigrants who had formerly immigrated to the UK.

Figure 3.3: Outflow of migrants, who are former immigrants to the UK, by citizenship and previous main reason for immigration (year ending September 2014)

Source: nternational Passenger Survey (IPS) - Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Figures are provisional.

- 'Work-related reasons' is the sum of definite job and looking for work.

Download this chart Figure 3.3: Outflow of migrants, who are former immigrants to the UK, by citizenship and previous main reason for immigration (year ending September 2014)

Image .csv .xlsWork-related reasons and formal study were the two most common previous main reasons for immigrating to the UK, reported by those former immigrants who emigrated in the year ending September 2014, at 85,000 (42%) and 70,000 (35%) respectively. It should be noted that these IPS emigration flows reflect inward flows in previous years, not the current year.

An estimated 14,000 (7%) had previously immigrated to the UK to accompany or join another person, while 32,000 (16%) had previously immigrated for other reasons or did not state their previous reason for immigration.

Of those who had previously immigrated to the UK for work-related reasons, 48,000 (56%) were EU citizens, 13,000 (15%) were citizens of the Old or New Commonwealth, and 12,000 (14%) were citizens of other foreign countries.

Of the 70,000 emigrants who had previously immigrated to the UK for formal study, 19,000 (27%) were EU citizens and 31,000 (44%) were Other Foreign citizens. 17,000 (24%) were citizens of the Old or New Commonwealth, which shows a statistically significant decrease compared with the year ending September 2013 estimate of 22,000 (31%).

Using the new country groupings which ONS consulted on in 2014, the latest IPS estimates show that in the year ending September 2014, of those who had previously immigrated to the UK for work-related reasons, 13,000 (15%) were citizens of Asian countries. The estimates also show that, of those who had previously immigrated to the UK for formal study, 19,000 (27%) were East Asian citizens (this was a statistically significant increase from 13,000 (18%) in the year ending September 2013). There was a statistically significant decrease in estimates of South Asian citizens, from 24,000 in the year ending September 2013 to 17,000 in the year ending September 2014.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. List of products

The following are URL links to the products underlying this report, or otherwise associated with the co-ordinated migration release of 26 February 2015. The department releasing each product is indicated.

The MSQR User Information (ONS) (365.1 Kb Pdf) – guidance on interpreting confidence intervals, the difference between provisional and final estimates, and the comparability and quality of input data sources.

International Migration Statistics First Time User Guide (ONS) (315.4 Kb Pdf) – an introduction to the key concepts underpinning migration statistics including basic information on definitions, methodology, use of confidence intervals and information on the range of available statistics related to migration.

Guidance on revised net migration statistics (ONS) (55.9 Kb Pdf) – information for users on how to interpret the revised net migration estimates alongside published LTIM estimates.

Long-Term International Migration – Frequently asked Questions and Background notes (ONS) (442.3 Kb Pdf) – information on recent trends in migration, methods and coverage, comparisons to international migration estimates, a complete list of definitions and terms and a guide to the published tables.

Quality and Methodology Information for International Migration (ONS) (217.6 Kb Pdf) – information on the usability and fitness for purpose of long-term international migration estimates.

Long-Term International Migration estimates methodology (ONS) (930.8 Kb Pdf) – a detailed methodology document for LTIM estimates, including information on current methodology and assumptions, data sources including the International Passenger Survey and changes to the methodology since 1991.

International Passenger Survey: Quality Information in Relation to Migration Flows (ONS) (324.7 Kb Pdf) – an overview of the quality and reliability of the International Passenger Survey (IPS) in relation to producing Long-Term International Migration estimates.

Local Area Migration Indicators Suite (ONS) – This is an interactive product bringing together different migration-related data sources to allow users to compare indicators of migration at local authority level. This product is updated annually in August.

Migration Theme Page (ONS) – This provides the most up to date figures and highlights the latest summaries, publications and infographics for internal and international migration.

Population Theme Page (ONS) – This provides the most up to date figures and highlights the latest summaries, publications and infographics for different components that contribute to population change, including migration.

Overview of Population Statistics (ONS) – This describes different aspects of population we measure and why. Information on how these are measured, and the statistics themselves, can be found via the links provided within the document.

Population by Country of Birth and Nationality (ONS) – This short report focuses on annual and regional changes in the UK resident population by nationality and country of birth for the year ending December 2013. The product is published annually in August.

Short-Term International Migration annual report (ONS) – A report and tables detailing estimates of short-term migration to and from the UK for England and Wales for the year ending mid-2012. The product is published annually in May.

Quarterly releases on 26 February 2015:

Provisional Long-Term International Migration, year ending September 2014 (ONS)

Immigration Statistics, September to December 2014 (Home Office)

National Insurance Number (NINo) Allocations to Adult Overseas Nationals to December 2014 (DWP)

Annual releases on 22 May 2014:

Annual releases on 28 August 2014:

Annual releases on 27 November 2014:

Additional Useful links:

Labour Market Statistics, February 2015 (ONS). This includes estimates of the number of people in employment in the UK by country of birth and nationality.

Quality of Long-Term International Migration estimates from 2001 to 2011 (ONS) (1.04 Mb Pdf)

International Migration Timeline (ONS)

Final Long-Term International Migration (2013) (ONS)

A Comparison of International Estimates of Long-term Migration (ONS)

Migrant Journey Fifth Report (Home Office)

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys