Cynnwys

- Foreword

- Introduction

- International student migration has changed over the last 10 years

- International students are a component of net migration because not all students depart the UK when they have completed their studies

- International student journeys are complex and their migration intentions at the end of their studies may change

- The Home Office Exit Checks data provide a more accurate picture of what non-EU students do after their visa expires

- We have a better, but not complete, understanding of how students contribute to net migration

- This work does not provide evidence to suggest that these findings affect total net migration figures

- There is more work for the ONS team, in partnership with colleagues across the Government Statistical Service, to further improve migration statistics

1. Foreword

The Office for National Statistics continually reviews and improves the quality of our statistics to ensure that public debate is well informed. With the decision to leave the EU, we know there will be a focus on migration statistics. While recently this focus has been on student migration, other topics are highly likely to come up. As Deputy National Statistician for Population and Public Policy I want to set out our work on student migration and look wider to ensure we meet the full range of user needs on migration statistics.

A comprehensive update on the statistics on immigration for study and emigration after study has been published by ONS today. This is a major part of our work plan, published in April 2017, in response to debates on student migration. Currently, these statistics come from the number of people who report to the International Passenger Survey (IPS) that they are immigrating for study and experimental statistics on those intending to emigrate for 12 months or more, after having originally come to the UK to study.

Over the past 10 years, there have been significant policy changes which have impacted on migration for study purposes. The latest International Passenger Survey figures show that 139,000 people were long-term immigrants for study and 59,000 people were long-term emigrants following study.

Available sources1 have shown a broadly consistent picture of long-term immigration of non-EU students but until recently there has been no alternative data source to compare with IPS former student long-term emigration figures. Our work published today therefore focuses on this area.

This report and the complementary report2 by Home Office Statisticians sets out analysis of Exit Checks data which indicate what actually happened to non-EU students when their visas have expired following their studies; and their compliance with their visa conditions in terms of whether they leave the UK or remain in the UK after their studies by extending their visas. Additionally, we include the results of a new survey of graduating Higher Education students on their intentions following study.

The work of the statisticians across government suggests that recent cohorts of non-EU students are to a very large extent compliant with their visas in terms of departing or staying legally via extensions of leave.

This work crucially demonstrates two things:

that many people do not simply immigrate for study and leave afterwards; their lives are more complex – some people arrive on a work visa and legitimately change to a study visa and vice versa

there is no evidence of a major issue of non-EU students overstaying their entitlement to stay

At the end of study students are at a transition point in their life. This presents two issues which are particularly important when breaking down net migration by reason from survey data collected as people pass through airports, sea ports and the Channel Tunnel.

Firstly, people need to recall back to their first arrival under the visa not just the last visit. Students are often travelling back to home countries and so may not accurately report back to the original reason being study and so may appear in other categories.

Secondly, the Survey of Graduating International Students shows that for many students they have a high degree of uncertainty about what they will be doing next. This makes intentions for this group more challenging. Exit Checks data indicate actual outcomes as opposed to intentions. Our analysis confirms that a lower number of departing students return to the UK within 12 months compared to the number who reported such an intention when departing the UK.

This doesn’t provide evidence of an issue with overall net migration figures for two reasons; because (a) students emigrating might have stated their original reason for migration under the work category or other categories; and (b) a tendency for a particular group of migrants to change their intentions in one way may be offset by a different group of migrants with a tendency to change their intentions in the opposite way. For example, people emigrating after work or British emigrants returning earlier than expected. While we make some adjustments to account for changes in intentions, these need to be reviewed.

So my conclusions from this work are as follows:

That it remains legitimate to look at immigration by reason for those migrating to the UK and emigration by what people came here to do. But the data on those leaving is based on asking people to recall their original reason for arriving and is often asked when their intentions to return are uncertain. Users should therefore take caution in over-interpreting emigration by reason for originally coming to the UK.

The above work concludes that looking at net migration without full consideration of challenges of measuring emigration by original reason could mislead. Using current methods, net migration by reason for arrival is not a robust statistic. We would caution users from subtracting emigration after study numbers from immigration to study numbers without full consideration of the issues set out here.

We will work with statisticians across Government to continue to improve migration statistics, and in particular to develop a robust approach to measuring net migration by reason, but in the meantime we should no longer publish breakdowns of net migration by reason as these do not reflect the complexities of people’s lives.

But most importantly, we need to urgently move beyond debates on the quality of the International Passenger Survey. ONS have long acknowledged that the current demands of migration statistics are pushing the survey well beyond what it was designed for. The Digital Economy Act (2017) provides a platform to use administrative data from across Government to provide a far deeper and richer understanding of migration.

By using data from across Government we can provide greater statistical insight into the number of migrants, where they live, what they are doing, how long they have been here for and what the benefits and impacts are for local communities as well as providing a better understanding of net migration. This is not, however, a panacea. Administrative data also has limitations. In particular, you have to wait 12 months to know whether someone has become a long-term emigrant.

There is clearly a need for more timely data and the International Passenger Survey will play a valuable role as a leading indicator of net migration in our future system.

This is an ambitious programme and I have formed a cross-Government Statistical Group to come together to deliver this agenda. In September, I will set out fully the plans for improving our statistics further to help support the political and public debate.

Iain Bell

Deputy National Statistician for Population and Public Policy

Notes for: Foreword

- IPS long-term study for non-EU nationals, Home Office long-term study visas.

- Second report on statistics being collected under the Exit Checks programme (Home Office, August 2017).

2. Introduction

Overseas students contribute around a quarter of total immigration to the UK. There is a lot of interest into the different reasons why people migrate to and emigrate from the UK, and lately this has focused on students.

Our Migration Statistics Quarterly Reports1 include estimates of the number of international students who enter the UK to study (student immigration) and an estimate of the number who leave the UK to study (student emigration). Since 2012, it also includes an estimate of the number of former students emigrating from the UK (former student emigration).

We have recognised areas for improvement in the publication of international student migration data. Since 2016, we have published three updates on our student migration research. In February we set out plans more generally, to develop data sources for international migration and we will publish further detail in September 2017. This article introduces analysis based on new evidence that helps us in developing a better understanding of international student migration.

The analysis presented in this article is focused on non-EU student migration because non-EU nationals contribute around 70% of international student migration to the UK and are subject to immigration control. Evidence presented in this article is supported by a technical report, including Home Office data and the results of a new student survey. A separate report published by the Home Office provides a second update on the new Exit Checks data, including further analysis of that source relating to non-EU students. This article shows that:

international student migration has changed over the last 10 years

international students are a component of net migration

international student journeys are complex and their migration intentions at the end of their studies may change

the Home Office Exit Checks data provide a more accurate picture of what non-EU students do after their studies; this knowledge has given us greater insight into the International Passenger Survey (IPS) derived statistics, which are likely to underestimate student emigration and therefore, any implied student net migration figure is likely to be an overestimate

we have a better, but not complete understanding of how students contribute to net migration

this work does not provide evidence to suggest that these findings affect total net migration figures

there is more work for the team at Office for National Statistics (ONS), in partnership with colleagues across the Government Statistical Service, to improve further the migration statistics

Notes for: Introduction

- The latest Migration Statistics Quarterly Report was published on 24 August 2017.

3. International student migration has changed over the last 10 years

Figure 1: Long-term non-EU international immigration for study, 1991 to 2016, UK

Source: International Passenger Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Inflow for formal study is the estimate of immigrating students entering the UK long-term.

- Figure 1 shows calendar years only, however the latest available figures are provisional estimates for the year ending (YE) March 2017 that indicate 139,000 immigrated for study.

- Estimates for the calendar year 2016 are provisional and will become final on 30 November 2017.

Download this chart Figure 1: Long-term non-EU international immigration for study, 1991 to 2016, UK

Image .csv .xlsA number of operational and policy changes were made to UK immigration rules between 2010 and 2016. These changes are reflected in a fall in immigration for study since 2010, with much of this decrease concentrated in the Further Education sector.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. International students are a component of net migration because not all students depart the UK when they have completed their studies

Previously published Home Office analysis of non-EU students’ journeys through the immigration system shows that around 1 in 5 non-EU former students had valid leave to remain up to 5 years after their arrival to study as students or by switching visa routes. In addition, a small proportion (1%) had achieved settlement in 5 years.

Further evidence from the Survey of Graduating International Students shows that around a quarter of non-EU students responding to the survey state that they intend to work in the UK after completing their studies.

The main source of data that is currently used to measure migration into and out of the UK is the International Passenger Survey (IPS).

The published total net migration figure is an estimate of the difference between the numbers of people who are immigrating and the numbers who are emigrating for 12 months or more. All people migrating to or from the UK are included in the total figures regardless of their nationality or reason for migrating.

Immigrants are identified in the IPS as people who:

- have lived abroad for 12 months or more prior to their arrival in the UK

- intend to live in the UK for 12 months or more

Emigrants are identified in the IPS as people who:

- have lived in the UK for 12 months or more prior to their departure from the UK

- are intending to live abroad for 12 months or more

Currently, students are identified in the IPS as those whose answers meet these criteria in addition to stating that they are arriving to study; and when they emigrate they state that they previously immigrated to study.

Figure 2 shows that since data on emigration of former students was collected from 2012, there has been a “gap” between the numbers of non-EU students immigrating long term and the numbers of former students emigrating long term.

Figure 2: Immigration for study and emigration of former student immigrants, non-EU nationals, 1991 to 2016, UK

Source: International Passenger Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Inflow for formal study is the estimate of immigrating students entering the UK long-term.

- The above shows calendar years only, however the latest available figures are provisional estimates for the year ending (YE) March 2017 that indicate 139,000 immigrated for study.

- Estimates for the calendar year 2016 are provisional and will become final on 30 November 2017.

- The inflows for formal study are Long-Term International Migration estimates (LTIM). LTIM estimates include a number of adjustments, including for people who change their intentions (switchers).

Download this chart Figure 2: Immigration for study and emigration of former student immigrants, non-EU nationals, 1991 to 2016, UK

Image .csv .xlsThe “gap” between the immigration of international students and the emigration of former students implies that the contribution of non-EU students to the total net migration figure of overseas students is typically around 50,000. However, we would not expect the numbers to be the same because not all students leave the UK at the end of their studies.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. International student journeys are complex and their migration intentions at the end of their studies may change

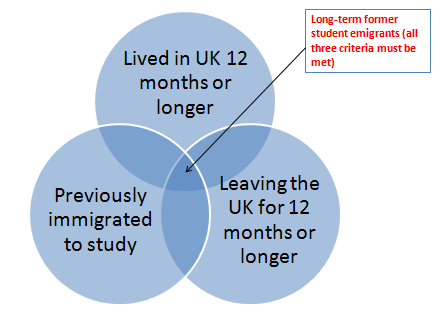

Figure 3 shows how the answers provided to the International Passenger Survey (IPS) categorise departing passengers as former international student immigrants who are now emigrating from the UK.

Figure 3: How the International Passenger Survey identifies emigration of former international students

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 3: How the International Passenger Survey identifies emigration of former international students

.png (17.1 kB)The answers provided by students who emigrate following their studies need to meet all three criteria to be categorised as a long-term emigrating former student. Our analysis of Exit Checks data and the Survey of Graduating International Students is discussed further in this section.

Students may be likely to overstate their intentions to return to the UK compared with actual behaviour

When non-EU former students were departing the UK in 2015 and 2016, just over a quarter (28%) stated that they were unsure how long they would be out of the UK or that they intended to return within 12 months1. Exit Checks data suggest the proportion of non-EU students who actually returned is much lower at around 6%.

When departing, students may say that they have been in the UK for a shorter time than they actually have

International students who travel abroad several times during their studies may understate their duration when asked how long they have been living in the UK.

The majority of international students (70%) who responded to the graduate survey said they had travelled outside the UK in the Christmas, Easter or summer holidays during the previous year. While IPS interviewers are trained to exclude short trips abroad when establishing length of residency, for some departing students, it seems plausible that they may respond to the IPS with the duration since their last return to the UK, which may be within the last 12 months.

Emigrating former students may state a different reason for previously immigrating to the UK

The IPS asks a person’s main reason for migration. This may or may not be the same as the visa they are travelling on. Home Office data show that in 2016, around one in five visa extensions were for non-study visas, which means that a former student remained in the UK for work, family or other reasons. When they eventually emigrate, they may not state “study” as their previous main reason for immigration.

These reasons contribute to understanding why the IPS may underestimate actual emigration of previous student immigrants.

To better understand what happens to international students, we also need to understand migration patterns, not just of those that have recently finished their studies, but also those who have studied, but continued to stay in the UK, for legitimate reasons, for a period of time after their study period. The IPS alone does not collect all of this information and needs to be viewed along with other data sources to provide a more complete picture of what students do after their studies.

Notes for: International student journeys are complex and their migration intentions at the end of their studies may change

- Further information from the Survey of Graduating International Students of how certain students are of their post-study intentions can be seen in Figure 3 of the International Student Migration Research Update.

6. The Home Office Exit Checks data provide a more accurate picture of what non-EU students do after their visa expires

The International Passenger Survey (IPS) records migration intentions, which may be more likely to reflect actual behaviour when immigrating long-term to the UK (because students will have registered on their courses and are asked about these by interviewers). This is supported by the historical close patterns seen in IPS data and other sources. However, evidence shows that these intentions are less likely to reflect actual behaviour on departure, because post-study plans are likely to be less certain, and personal circumstances will change.

Whilst in the UK, non-EU students may apply for leave to remain in the UK (for further study, to work, or for another reason), they may leave the UK temporarily intending to return, or they may emigrate long-term. This complexity of different behaviours and a strong likelihood that international students are more flexible with their plans than some other types of migrants, such as those with family ties, mean that what they tell the IPS their intentions are, as they leave the UK, may not reflect what they actually do.

New analysis of Exit Checks data shows that 69% of the international students who immigrated on a long-term visa (12 months or more) and whose visa or extension of leave to study expired in 2016 to 2017, left the UK. A further 26% extended their visas to remain in the UK for further study or for other reasons such as work. The remainder have no identified record of departure or extension, or appeared to depart after their visa had expired.

Exit Checks data following up non-EU former students who departed in 2015 and 2016 indicated that 77% emigrated long-term after their studies (didn’t return within 12 months); 15% returned on a short-term visit visa and departed again within 12 months; and 6% returned on a long-term visa (12 months or more) for work or other reasons.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. We have a better, but not complete, understanding of how students contribute to net migration

We now know that there is strong evidence to suggest that the International Passenger Survey (IPS) is likely to underestimate student emigration, therefore any attempt to estimate the contribution that students make to net migration is likely to be an overestimate. There is evidence to suggest that for this particular group of immigrants, their intentions (as stated to the IPS) don’t accurately reflect their actual migration patterns.

We don’t yet have reliable data to measure fully the extent to which these intended behaviours match actual migration behaviours.

Exit Checks data provide an improved and developing measure of the actual long-term departure behaviour of non-EU students, but this is only possible once repeated entries and exits have been identified and linked in the data to separate migrants from short-term visitors. Additionally, Exit Checks data don’t provide information about EU or UK nationals migrating internationally to study, which will be necessary to assess how all international students contribute to net migration.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. This work does not provide evidence to suggest that these findings affect total net migration figures

There are possible reasons why we think these findings may not affect total net migration figures, which are detailed in this section.

Emigrating students who gave a different previous reason for immigration may potentially be included in other categories, for example “work” or “accompany or join”. Therefore, while they aren’t separately identified as previous student immigrants, they will be included in the total figures.

There may potentially be some “offsetting” with other groups of migrants who will contribute to the total net migration figures in other ways. For example, there could be a group of emigrants who have a tendency to understate their duration from the UK – perhaps British emigrants who return home earlier than intended.

Total net migration figures include an adjustment for people who change their migration intentions. This is an adjustment to the overall figures for long-term international migration (for estimating the population) and isn’t applied to more detailed breakdowns such as reason for migration by nationality. It isn’t currently possible to separate out this adjustment for students as a particular group.

All these possible reasons require further investigation before any conclusions can be reached about the benefit of further adjustments to total net migration figures.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. There is more work for the ONS team, in partnership with colleagues across the Government Statistical Service, to further improve migration statistics

This report takes us a significant way forward in better understanding how the International Passenger Survey (IPS) is measuring student migration, but there is more to do. We believe that working in partnership with government departments and other stakeholders improves the quality and relevance of our analysis. We will continue to strengthen the way in which we work with those who can help us.

Our future work will involve a re-examination of the adjustment made to account for changes in intentions that is currently part of our statistical methodology. We will also examine Exit Checks data for other groups of migrants who are on work or family visas.

Further work is planned to identify how sharing, linking and exploiting other sources of data can help produce additional insight to help us understand patterns of international migration. We aim to link with more administrative data held by government departments and we will publish updates on the progress of this work and other plans to make better use of data (administrative data, survey data and census data).

We will continue to publish updates on the progress of this work and other plans to make better use of data across our priority areas to understand the impact of migration on the economy and labour market.

The Digital Economy Act 2017 provides an opportunity to move beyond the current limitations of the statistics by more fully integrating the administrative data held across government to provide greater depth of statistical knowledge on:

- how many migrants are in the country and what are they doing here?

- how long have people been here and where are they within the UK?

- recognition that for many the distinction between long-term and short-term migrants isn’t helpful in understanding the impact of international migration in the UK; however, for measuring the population as a whole, long-term migration is essential

- administrative data could potentially measure long-term migration, but with significant delays as we would need to wait 12 months then process the data to get an answer (and even longer for Census results); however, a timely indicator of long-term net migration is essential and the IPS will provide a useful leading intentions-based indicator, and will continue to play an essential feature of any system