Cynnwys

- Main points

- Introduction

- Overall trend

- Exploring the definitional differences between the two sources

- Investigating the difference between the International Passenger Survey and the Annual Population Survey for specific groups of migrants

- What are the methodological differences between the two surveys?

- Next steps

- Annex A

1. Main points

The latest population of the UK by country of birth and nationality estimates are measured using the Annual Population Survey (APS). The APS is not designed to measure Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) but does give insights into changes in the population. While for overall international migration the long-term trends are similar the APS has shown different patterns to LTIM for changes in EU and non-EU migration. The most recent figures for overall migration are also further apart than we have seen previously.

We published a workplan in February 2019, which also considers the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and once complete, will help us to better understand the reasons for these differences. The aim of this report is to share the initial findings of our research into the coherence of these sources. We are keen to gather your views on these initial findings to feed into our future research. We will aim to complete this work by summer 2019 to help us better understand trends in migration from all sources, and to feed into our reporting and our transformation programme.

Key findings from our work to date include:

- our exploration of the definitional differences between the sources suggest that they do contribute to the divergent patterns we can see but that they are not sizeable enough to fully explain them

- there are many country groups for which the change in the APS stocks and LTIM net migration are showing similar patterns and the small differences seen are likely to be due to definitional and survey design differences; however, for a few groups there are larger differences that require further investigation

- within EU migration the divergence between the two sources is driven primarily by those from central and eastern European (EU8) countries, where the annual change in the APS stocks is much higher than LTIM net migration as estimated by the International Passenger Survey (IPS)

- within non-EU migration the divergence between the two sources is driven primarily by those from Asia where the annual change in the APS stocks is much lower than LTIM net migration as estimated by the IPS

- our next steps will therefore be building on the work we have done so far as set out in our workplan and Section 7

2. Introduction

In December 2016, we published an article explaining the definitional differences between the different data sources that measure international migration to and from the UK. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) produces several series of statistics on international migration:

- those that provide information on the flow (or movement) of international migrants

- those that estimate the stock (or resident population) of non-UK born people or nationals living in the UK.

We published a workplan in February 2019, which also considers the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and once complete, will help us to better understand the reasons for these differences. The aim of this report is to share the initial findings of our research into the coherence of these sources. In particular, we start to quantify the definitional differences between the surveys, explore how the divergence between the sources varies for different groups and takes a brief look at how the weights in the Annual Population Survey (APS) have changed over time.

In May 2019, we held a workshop with some of our key stakeholders to discuss our initial findings and gather their views on the work so far and to discuss the next steps to take. This workshop has helped us shape the research and we are keen to gather further views on these initial findings to feed into our future research.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Overall trend

In theory, the change in the number of non-UK born people living in the UK from year-to-year should be close to the net flow of non-UK born people into the UK. However, while both the International Passenger Survey (IPS) and Annual Population Survey (APS) have value, they are not directly comparable in this way as they have fundamental coverage and sampling differences. They are designed to measure different aspects of migration, in different ways, based on different types of data, and neither has complete coverage.

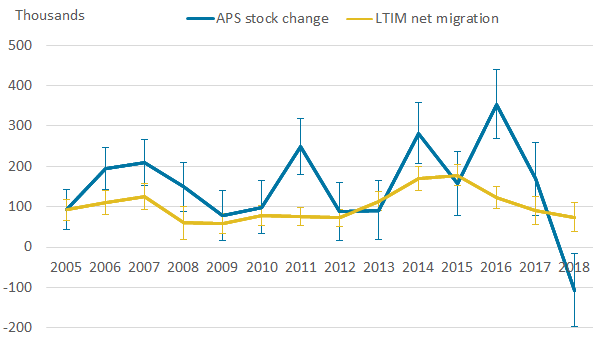

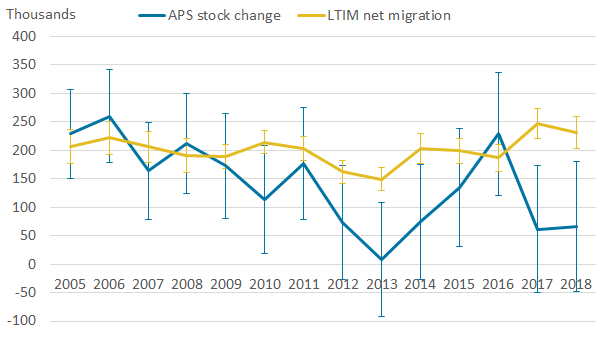

Our work to date shows that when comparing the change in stocks as reported by the APS and the Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) net flows for the non-UK population over an extended time period (2005 to 2018) there is a discrepancy in the two series (Figures 1 and 2). The annual changes in non-UK APS stocks show a highly variable pattern when compared to the more stable LTIM net migration. For EU migrants, whilst in most years the yearly change in the APS stocks is higher than LTIM net migration, in 2018 the pattern is different. For non-EU migrants, in most years the yearly change in the APS stocks are lower than LTIM net migration.

Figure 1: Comparison of LTIM net migration estimates and the annual change in the APS estimates of the population, EU-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this image Figure 1: Comparison of LTIM net migration estimates and the annual change in the APS estimates of the population, EU-born population, 2005 to 2018

.png (14.8 kB) .xls (64.5 kB)

Figure 2: Comparison of LTIM net migration estimates and the annual change in the APS estimates of the population, non-EU born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this image Figure 2: Comparison of LTIM net migration estimates and the annual change in the APS estimates of the population, non-EU born population, 2005 to 2018

.png (19.7 kB) .xls (65.5 kB)Over time the year-on-year differences between the two sources accumulate meaning the cumulative long-term differences gradually increase. Figure 3 shows between 2005 and 2018 the cumulative change in the APS stocks for EU migrants is much higher than LTIM net migration and for non-EU migrants the cumulative change in the APS stocks are much lower than LTIM net migration.

Some of these differences will be explained by the different definitions used in the two sources and the way each survey collects the data.

Figure 3: Cumulative APS stock change and LTIM net migration, Non-UK country of birth, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 3: Cumulative APS stock change and LTIM net migration, Non-UK country of birth, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls4. Exploring the definitional differences between the two sources

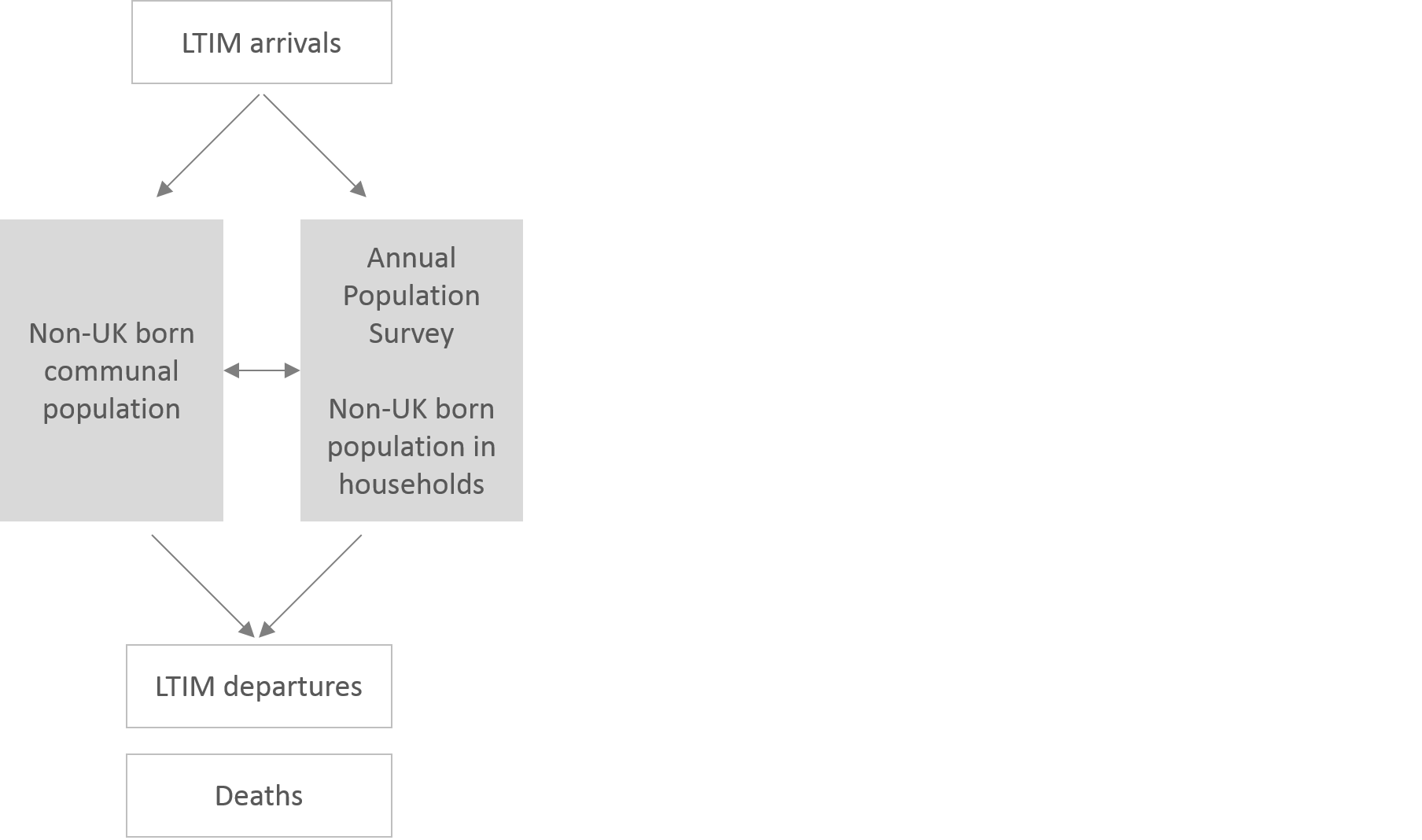

There are coverage and definitional differences that mean the Annual Population Survey (APS) and the International Passenger Survey (IPS) will never fully reconcile. The workplan published in February 2019 outlined the main definitional differences between the two surveys. Work package 4 was set up to explore these definitional differences and assess the impact on the divergence.

Figure 4 shows the theoretical relationship between the two sources, where the IPS measures people who stay in the UK for 12 months or more whereas the APS includes anyone who considers the sampled address as their main residence, or who has been resident there for at least six months regardless of if they consider it their main residence. This means the APS will be including some short-term migrants who are not covered by the Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) definition of migrants who plan to stay for 12 months or more.

Figure 4: Relationship between the APS and the IPS definitions

Download this image Figure 4: Relationship between the APS and the IPS definitions

.png (43.5 kB)The APS does not include communal establishments in the sample, therefore will not include any migrants who are living in communal establishments. Using data from the 2011 census the total number of people with a non-UK country of birth living in communal establishments was 178,000. Most were those living in education related accommodation (123,000) or medical and care establishments (18,000) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: All usual residents born outside the UK living in communal establishments by type of establishment and passport held, census 2011

England and Wales

Source: Office for National Statistics – Census 2011

Notes:

1.Excludes people who said they did not hold a passport.

Download this chart Figure 5: All usual residents born outside the UK living in communal establishments by type of establishment and passport held, census 2011

Image .csv .xlsThe APS, therefore will not measure the change in the student population living in halls of residence. Since 2011 to 2012 the number of non-UK domiciled students living in communal establishments has increased by 40,000 to 188,000 in 2016 to 2017 (Table 1). While we can see that there has been an increase in this population we need to further explore how this has changed separately for EU and non-EU students to understand this further. However, as this increase is relatively small in comparison to the overall differences we are seeing between the sources, we expect that this is only one factor in building our understanding.

| Thousands | ||

|---|---|---|

| Academic Year | All | Non-UK domiciled students |

| 2011 to 2012 | 417 | 149 |

| 2012 to 2013 | 424 | 163 |

| 2013 to 2014 | 445 | 174 |

| 2014 to 2015 | 461 | 176 |

| 2015 to 2016 | 480 | 180 |

| 2016 to 2017 | 501 | 188 |

Download this table Table 1: Number of places in communal student establishments, academic year ending 2012 to academic year ending 2017

.xls .csvThe yearly change in the APS stocks do not account for the deaths of non-UK born migrants. Table 2 shows that each year there are around 50,000 deaths registered to those with a non-UK country of birth. Around 30,000 of these are those with a non-EU country of birth and around 20,000 with an EU country of birth. To make the yearly change in the APS stocks comparable to IPS net migration the APS estimates will need to be adjusted to account for these deaths. However, as the yearly adjustment is relatively small in comparison to the overall differences we are seeing between the sources we expect that this is only one factor in building our understanding.

| Thousands | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of birth | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| UK | 530,454 | 533,856 | 514,568 | 515,932 | 507,057 | 521,173 | 527,473 | 520,393 | 548,709 | 542,605 | 551,445 |

| EU | 20,233 | 20,708 | 20,029 | 20,275 | 19,975 | 20,847 | 20,971 | 21,041 | 22,371 | 22,356 | 22,500 |

| Non-EU | 22,706 | 23,775 | 23,610 | 24,024 | 23,831 | 25,493 | 26,145 | 27,006 | 29,326 | 29,662 | 30,605 |

| Not specified | 1,294 | 1,358 | 1,410 | 1,435 | 1,369 | 1,511 | 1,869 | 1,901 | 2,376 | 2,583 | 2,622 |

Download this table Table 2: Deaths registered in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, 2007 to 2017 by country of birth

.xls .csv5. Investigating the difference between the International Passenger Survey and the Annual Population Survey for specific groups of migrants

This section explores work package 5 in our workplan, which was set up to explore which groups are contributing most towards the divergence between the cumulative change in the Annual Population Survey (APS) stocks and Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) net migration. The charts for all country groups can be found in the Annex of this report. Here we focus on the countries showing the largest differences between the two sources for both EU and non-EU.

Which groups are driving the divergence for EU born migrants?

Looking at trends for EU-born migrants the divergence between the change in the APS stocks and LTIM net migration has occurred throughout the whole time series with the APS showing consistently higher totals. By 2018 the APS is showing a cumulative change of 2.1 million compared to 1.4 million cumulative LTIM net migration (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 6: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xlsFor migrants born in the 14 states of the EU (not including the UK) that were members of the EU prior to the 2004 accessions (EU14), the pattern as shown in Figure 7 is different to the overall EU total, where for EU14-born migrants LTIM net migration is slightly higher than the change in the APS stocks across the whole time-series. By 2018 cumulative LTIM net migration is 114,000 higher than the cumulative change in the APS stocks.

Figure 7: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU14-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 7: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU14-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xlsThe overall EU pattern is driven by those born in the central and eastern European countries (EU8 – who joined the EU in 2004), where in most years the change in the APS stocks has been much higher than LTIM net migration which is causing the divergence to grow over time (Figure 8). By 2018 the difference between the two sources is 640,000 with the cumulative change in the APS being more than double LTIM net migration.

Figure 8: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU8-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: : Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 8: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU8-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xlsIn 2012 ONS published a report, Quality of Long-Term International Migration estimates from 2001 to 2011 (PDF, 1MB), outlining the methods used to revise the national population estimates between mid-2002 to mid-2010. A reconciliation exercise carried out in light of the 2011 census found a difference of 464,000 between the census population estimate and the rolled forward mid-year population estimates. It was found that the single largest cause of this is likely to be the underestimation of long-term immigration from central and eastern Europe (EU8 countries) in the middle part of the decade. This was due to limitations in the coverage of the IPS at this time where it did not cover some regional airports such as Stanstead and Luton. The 2012 report Methods used to revise the national population estimates for mid-2002 to mid-2010 (PDF, 171KB) estimated that this accounted for 250,000 of the difference and estimated the distribution of this difference over time. With this adjustment applied to the cumulative LTIM net migration for the EU8 country group, the gap between LTIM net migration and the change in the APS stocks slightly narrows (Figure 9). However, the change in APS is still higher than LTIM net migration over the whole timeseries with the divergence growing year on year until 2017.

We will continue to explore these differences further and publish our conclusions in summer 2019.

Figure 9: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population with adjusted net migration adding on EU8 undercount up to 2011

EU8-born population, 2005 to 2018, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional

Download this chart Figure 9: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population with adjusted net migration adding on EU8 undercount up to 2011

Image .csv .xlsFrom 2011 the APS has collected data on reason for initial migration to the UK. Figure 10 shows most of the growth since 2011 for EU8 migrants has been those who initially migrated here for work or to accompany or join family.

It is not possible to compare this to the IPS as we cannot calculate net migration by reason for migration. This is because someone’s reason for leaving the UK might be different to their reason for initially moving to the UK, so it is not possible to match the two reasons together. As part of our future analysis we will look at reason for migration on inflow from the IPS and compare this to the APS looking just at those who arrived in the previous year and their reason for migration to see if this helps us further understand the difference.

Figure 10: Cumulative annual differences in APS estimates of the population by reason for migration, EU8-born population, 2012 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – Annual Population Survey

Download this chart Figure 10: Cumulative annual differences in APS estimates of the population by reason for migration, EU8-born population, 2012 to 2018

Image .csv .xlsWhich groups are driving the divergence for non-EU born migrants

Looking at trends for non-EU born migrants the divergence between the change in the APS stock and LTIM net migration has occurred mainly from 2009 onwards, before this the two series were showing similar levels (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, non-EU born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 11: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, non-EU born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xlsLooking at the two main country groups that make up non-EU migration “Asia” and “Rest of the world”, Figure 12 shows that the pattern for Asian-born migrants is driving the pattern for non-EU.

Figure 12: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 12: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xlsAsia

Looking further into the patterns within Asian-born migrants; East Asia and South Asia are the main drivers of the trend for Asia as a whole. The divergence between the two series is greatest for East Asia (Figure 13), by 2018 LTIM net migration is almost four times higher than the change in the APS stock (480,000 compared with 127,000). For South Asia the two series start to diverge from 2010 onwards and by 2018 LTIM net migration is higher than the change in the APS stock (940,000 compared with 670,000). We will continue to explore these differences further and publish our conclusions in summer 2019.

Figure 13: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, East Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

- East Asia includes; China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Macao, Mongolia and Taiwan.

Download this chart Figure 13: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, East Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 14: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, South Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

- South Asia includes; Bangladesh, Bhutan, British Indian Ocean Territory, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Download this chart Figure 14: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, South Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls6. What are the methodological differences between the two surveys?

As part of our work to investigate the divergence between the Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) flows produced using the International Passenger Survey (IPS) and the change in the estimates of the non-UK born population measured by the Annual Population Survey (APS) we are exploring the methodological differences between the two surveys. This includes understanding the impact of methodological changes in each survey, quantifying them where we can, as well as the changing response rates and the effect this has on the weighting including outliers.

From 2014 the number of non-UK born contacts in the APS has been decreasing year on year, although in 2018 the number of contacts is higher than pre-2011 levels (Table 3). The average weight size has gradually increased from 200 in 2005 to 286 in 2018. Looking at the distribution of the weights in 2010 there appears to be a large increase in the number of contacts with a weight size over 400, with almost 20 contacts having a weight size over 1,100 for the first time. By 2018, 121 non-UK born contacts had a weight size larger than 1,100.

We will further investigate the impact of the increasing weight size on the APS estimates of stock change and also look at the size of the weights in the IPS.

| UK | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Average weight | 200 | 207 | 210 | 213 | 224 | 230 | 235 | 234 | 233 | 236 | 246 | 267 | 276 | 284 |

| 0 to 99 | 5,903 | 5,757 | 5,786 | 5,381 | 4,790 | 4,804 | 4,547 | 5,255 | 5,596 | 5,819 | 5,532 | 4,482 | 4,442 | 4,123 |

| 100 to 199 | 8,537 | 9,043 | 9,172 | 10,444 | 10,499 | 10,598 | 10,954 | 10,993 | 11,287 | 11,279 | 10,580 | 10,293 | 9,607 | 9,417 |

| 200 to 299 | 8,378 | 8,393 | 8,621 | 8,776 | 7,852 | 7,192 | 7,581 | 7,106 | 7,444 | 7,988 | 7,799 | 6,654 | 6,657 | 6,409 |

| 300 to 399 | 4,115 | 4,843 | 5,423 | 5,519 | 5,635 | 5,362 | 5,721 | 6,108 | 5,571 | 5,567 | 5,778 | 6,220 | 5,967 | 5,177 |

| 400 to 499 | 679 | 935 | 1,182 | 1,304 | 1,966 | 2,418 | 2,586 | 2,769 | 2,724 | 2,850 | 3,066 | 4,065 | 4,250 | 4,168 |

| 500 to 599 | 213 | 202 | 226 | 237 | 540 | 763 | 758 | 797 | 848 | 1,004 | 1,277 | 1,591 | 1,791 | 1,890 |

| 600 to 699 | 42 | 16 | 27 | 61 | 92 | 176 | 254 | 209 | 259 | 351 | 489 | 531 | 621 | 963 |

| 700 to 799 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 16 | 61 | 57 | 57 | 136 | 123 | 150 | 235 | 296 | 434 |

| 800 to 899 | 4 | . | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 25 | 26 | 50 | 49 | 62 | 104 | 122 | 147 |

| 900 to 999 | . | . | . | 1 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 24 | 27 | 34 | 45 | 73 | 58 |

| 1000 to 1099 | . | . | . | . | . | 5 | 9 | 9 | 17 | 27 | 21 | 34 | 41 | 30 |

| 1100 and over | . | . | . | . | . | 19 | 43 | 45 | 54 | 61 | 57 | 85 | 138 | 121 |

| Total | 27,875 | 29,192 | 30,443 | 31,727 | 31,393 | 31,413 | 32,545 | 33,389 | 34,010 | 35,145 | 34,845 | 34,339 | 34,005 | 32,937 |

Download this table Table 3: Number of non-UK born contacts in the APS by weight size, 2005 to 2017

.xls .csv7. Next steps

Our work to date has shown that while the definitional differences between the sources do contribute to the divergent patterns we can see, they are not sizeable enough to fully explain them.

Our exploration of how different country of birth groups contribute to the divergent patterns has revealed that for many groups the two sources do show similar patterns, and that any small differences are most likely to be a result of definitional and survey design differences. For a few groups, however, there are large differences – these are particularly EU8, East Asia and South Asia.

Our next steps will therefore be to build on the work we have done so far as set out in our workplan.

We will investigate the impact of non-response on the survey estimates for the APS. In 2011, a Census Non-Response Link Study (PDF, 169KB) was conducted to assess non-response within the Labour Force Survey. We will further explore these findings to try to help us understand how these impact on our outputs.

We will also investigate how falling response rates affects the weighting (particularly for outliers) and how these impact on the estimates for both the International Passenger Survey (IPS) and Annual Population Survey (APS).

We will attempt to adjust the comparisons to account for changes in the student population in halls of residence and for deaths of non-UK born people that will provide us with a much clearer comparison between the two sources, and the size of the remaining difference.

For those groups contributing most to the differences between the sources, our next steps will be to focus on further exploring the year of arrival data in the Annual Population Survey (APS). This includes comparing the year of arrival on the APS to the International Passenger Survey (IPS) inflow and looking at arrival cohorts in the APS over time. We will use the IPS inflow compared to APS year of arrival to look at differences by reason for migration to see which reasons are being measured by each survey. We will also attempt to undertake some further exploration based on the demographic characteristics of migrants.

We will also further explore the policy changes made since 2005 to assess the impact on each data source. We will further explore the impact of short-term international migration and circular migration to identify if this helps to explain any of the divergence between the two sources. We will progress our work to explore the IPS evaluation of imbalance for travel and tourism estimates to identify what impact this may have on migration estimates. We will also continue to explore the available administrative data and assess whether this can help to triangulate the APS and IPS estimates.

We will also consider how estimates produced from the APS and LFS compare, and how this may impact on our analysis.

We will publish our conclusions to this research in Summer 2019. The conclusions to this work will inform our wider migration statistics transformation programme.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Annex A

Figure 15: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 15: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 16: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU14-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 16: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU14-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 17: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU8-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 17: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU8-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 18: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU2-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 18: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, EU2-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 19: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, non-EU born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 19: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, non-EU born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 20: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 20: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 21: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, "Rest of the World"-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 21: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, "Rest of the World"-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 22: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, East Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

- East Asia includes; China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Macao, Mongolia and Taiwan.

Download this chart Figure 22: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, East Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 23: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, South Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

- South Asia includes; Bangladesh, Bhutan, British Indian Ocean Territory, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Download this chart Figure 23: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, South Asian-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 24: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, Sub Saharan and North African-born population, 2005 to 2018

UK

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey, Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional.

Download this chart Figure 24: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population, Sub Saharan and North African-born population, 2005 to 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 25: Comparison of cumulative LTIM net migration estimates and annual differences in APS estimates of the population

North American, Central and South American and Oceania-born population, UK, 2005 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – International Passenger Survey and Annual Population Survey

Notes:

- For 2018 LTIM migration, nationality has been used instead of country of birth as a proxy, country of birth data is not due to be published until November 2019.

- 2018 data is provisional