Cynnwys

- Main points

- Introduction

- Data sources and analysis

- EU Overview

- EU15 (excludes British citizens)

- EU8

- EU2

- Next steps

- Annex 1 – International Passenger Survey - Long-Term and Short-Term International Immigration Assumptions

- Annex 2 - National Insurance registrations to adult overseas nationals

- Annex 3 - Non-UK nationals’ interaction with HM Revenue and Customs compared to National Insurance Number registrations and Long-Term International Migration

- Glossary

1. Main points

Short-term migration to the UK largely accounts for the recent differences between the number of long-term migrants (as estimated by the International Passenger Survey (IPS)) and the number of National Insurance number (NINo) registrations for EU citizens.

IPS continues to be the best source of information for measuring long-term international migration (LTIM).

Definitional differences between these data are fundamental and it is not possible to provide an accounting type reconciliation that simply ‘adds’ and ‘subtracts’ different elements of the NINo registrations to match the LTIM definitions.

NINo registrations data are not a good measure of LTIM, but they do provide a valuable source of information to highlight emerging changes in patterns of migration.

Work on NINo interactions data supports these conclusions, but this is complex work and will need further consideration. We intend to continue to work on these data sources and hope to be able to publish further analysis in due course.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Introduction

2.1 On 7 March ONS published an information note explaining the reasons why long-term international immigration figures from the IPS could differ from the number of NINo registrations. It noted that the two series are likely to differ because of short-term immigration and timing differences between arriving in the UK and registering for a NINo. This note presents an initial analysis that has been undertaken by experts across government to help understand why the two series are diverging, with a focus on EU migration particularly from the EU8 and EU2, where the recent differences between the two series have been most pronounced.

2.2 The analysis uses a range of administrative and survey data sources and requires looking at Government databases from a new perspective. This is complex work and will take time to complete. Given the considerable interest in this subject, ONS has decided to publish a note of our analysis now.

2.3 This paper concludes that, on the basis of the available evidence, the divergence between the NINo registrations and the Long-Term Immigration series from the IPS is likely to be largely due to short-term immigration and that estimates derived from the IPS remain the most appropriate for measuring long-term immigration.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Data sources and analysis

3.1 The data sources we have looked at are:

a) Short-term International Migration (STIM) data. The IPS can identify short-term migrants who arrive for employment, study or work (other) purposes for between 1 to 12 months. Up until 2014 it can identify the actual number of short-term migrants in England and Wales by analysing information from those leaving the country. An ad hoc analysis has also been run to estimate the number of short-term migrants in 2015 using ‘intentions’ data which are only available for the UK as a whole. The inclusion of short-term intentions data for mid-2015 provides a good indication of whether the recent sharp rise in NINo registrations could be related to short-term immigration, which you would not expect to see reflected in Long-Term International Migration (LTIM) figures (12 months or more) and therefore the headline net migration figure. Since people's intentions can change, these data will not be directly comparable with the mid-2015 estimates of 'actual' short-term migration, which will be published in May 2017. However, the short-term intentions data do represent a recent flow of people arriving in the UK who may apply for a NINo. Two estimates of the STIM 2015 figures have been included in this paper to reflect the uncertainty and the fact that they can be estimated in a number of different ways. The charts presented below include actual STIM estimates up until 2014 and use two short-term intentions estimates for 2015. The assumptions used to create the STIM intentions estimates in this paper are given in Annex 1.

b) ‘Interactions data’ – The analysis of these data for this purpose is relatively new and has not yet been fully explored. However, focusing on the trends and proportions the data are showing is still helpful and can be set alongside the IPS data for comparison. It should be noted that these represent three distinct pieces of analysis. Getting a coherent picture from all three is complex given that they use a combination of survey data and administrative data that cover both stocks and flows. Nevertheless, some general conclusions can be drawn and these are presented throughout this paper. The sources we are utilising are:

L2 – Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) analysis using the Lifetime Labour Market Database (L2), which is based on a 1% sample of NINos and collates data from National Insurance, PAYE, DWP Benefit and Local Authority benefit systems. The L2 holds individual interactions with these systems up to end March 2015.

SPI - HMRC analysis of those subject to income tax (PAYE or Self-Assessment) or National Insurance Contributions (NICs) or receiving Tax Credits or Child Benefit or any combination of these, from the Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI) and HMRC’s administrative data on tax credit and child benefit recipients, which are available up to end March 2013.

RTI/SA - HMRC analysis of employers’ payments for their employees’ income tax PAYE or occupational pensions in 2014-15 by submission to HMRC’s Real Time Information (RTI) system, supplemented by Self-Assessment (SA) data on the number of individuals who have filed a 2014-15 SA return who did not report employment, pension or taxable benefit income on their SA return.

More details on how the analysis has been carried out and the limitations of each source are included in Annexes 2 and 3 for information.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. EU Overview

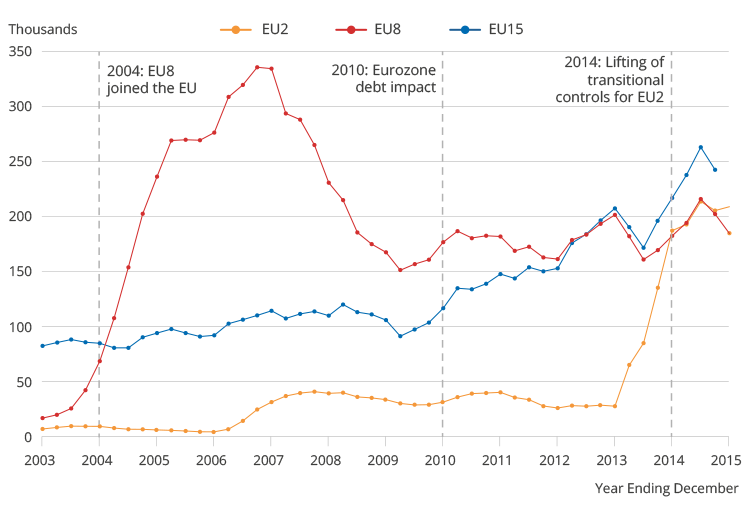

Figure 1: Overview of NINo Registrations data for EU citizens, year ending Dec 2003 to year ending Dec 2015

Source: National Insurance Numbers Registered to Adult Overseas Nationals - Department for Work and Pensions

Download this image Figure 1: Overview of NINo Registrations data for EU citizens, year ending Dec 2003 to year ending Dec 2015

.png (50.4 kB) .xls (31.7 kB)4.1 The sharp increase in NINo registrations is not a new phenomenon. Figure 1 above shows there have been sharp increases and decreases over the last 12 years which appear to have been driven by changes to the rights to access the labour market or economic factors. In particular, there was a sharp increase in the number of NINos allocated to EU8 citizens after their accession to the EU in 2004 followed later by a decrease. This appears to be mirrored by the marked increase in EU NINo registrations, largely driven by the number of EU2 citizens registering following their accession in 2014, though this has been partially reversed recently due to slight falls in EU8 and EU15 registrations.

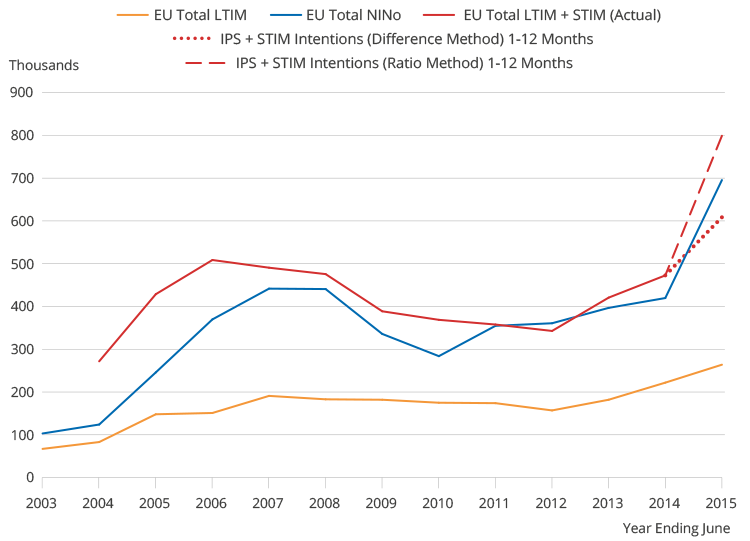

Figure 2: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

Source: Source: Long-term International Migration (LTIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: Short-term International Migration (STIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: National Insurance Numbers Registered to Adult Overseas Nationals - Department for Work and Pensions

Notes:

- Please see Assumptions section in Annex 1 for detail on the data used in the charts in this paper.

- Short-term migration estimates for the year to mid-2015 will be published in May 2017. However, the two provisional estimates of intended short-term migration are provided as an indication of people who arrived in this period and may have acquired a NINo. For more information, refer to Annex 1

- Note that for 2003 to 2014 the LTIM data are adjusted LTIM whereas for 2015 the data are IPS only to avoid double counting switchers who may appear in the STIM intentions data.

Download this image Figure 2: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

.png (41.4 kB) .xls (35.8 kB)4.2 As the March report set out, one of the main reasons for the divergence between LTIM and NINos is likely to be that LTIM does not (and is not intended to) pick up short-term migration. Consequently, when we add STIM data to LTIM data1 we can see that there is a much closer parallel between measured immigration and the numbers of NINo registrations, which is shown in figure 2 above.

4.3 Any remaining gap between LTIM + STIM and the NINo registrations data could potentially be explained by looking at the number of visitors that come to the UK for work or business for less than one month. In 2015 there were almost 5.9 million visitors that came to the UK for work or business. These visitors could be eligible to apply for a NINo and although the great majority will not, a small number are likely to need or use the opportunity to apply for one.

Notes for EU Overview

- Please note that the addition of LTIM and STIM do not provide a simple and accurate measure of all immigration to the UK within a specific time period. Please see Annex 1 for more information.

5. EU15 (excludes British citizens)

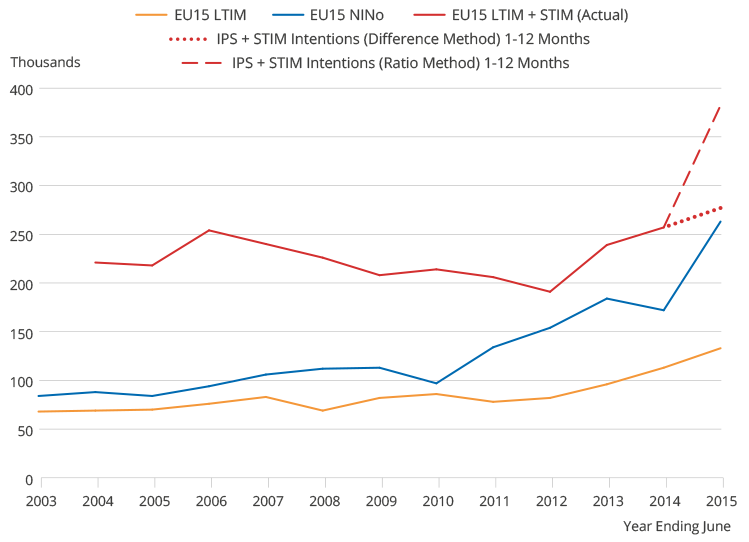

Figure 3: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU15 citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

Source: Long-term International Migration (LTIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: Short-term International Migration (STIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: National Insurance Numbers Registered to Adult Overseas Nationals - Department for Work and Pensions

Notes:

- Please see Assumptions section in Annex 1 for detail on the data used in the charts in this paper.

- Short-term migration estimates for the year to mid-2015 will be published in May 2017. However, the two provisional estimates of intended short-term migration are provided as an indication of people who arrived in this period and may have acquired a NINo. For more information, refer to Annex 1

- Note that for 2003 to 2014 the LTIM data are adjusted LTIM whereas for 2015 the data are IPS only to avoid double counting switchers who may appear in the STIM intentions data.

Download this image Figure 3: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU15 citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

.png (36.3 kB) .xls (34.8 kB)5.1 Figure 3 above shows that when STIM data are added to LTIM data the level of international immigration is above the number of NINo registrations for EU15 citizens. This may reflect that citizens in these countries are used to having freedom of movement and many of those arriving will be repeat visitors and therefore already have a NINo.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. EU8

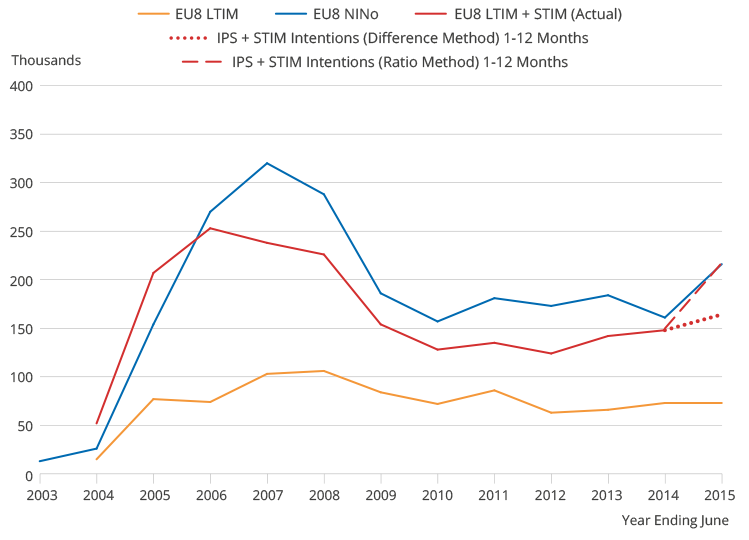

Figure 4: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU8 citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

Source: Long-term International Migration (LTIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: Short-term International Migration (STIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: National Insurance Numbers Registered to Adult Overseas Nationals - Department for Work and Pensions

Notes:

- Please see Assumptions section in Annex 1 for detail on the data used in the charts in this paper.

- Short-term migration estimates for the year to mid-2015 will be published in May 2017. However, the two provisional estimates of intended short-term migration are provided as an indication of people who arrived in this period and may have acquired a NINo. For more information, refer to Annex 1

- Note that for 2003 to 2014 the LTIM data are adjusted LTIM whereas for 2015 the data are IPS only to avoid double counting switchers who may appear in the STIM intentions data.

Download this image Figure 4: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU8 citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

.png (43.2 kB) .xls (34.8 kB)6.1 EU8 countries gained the right to free movement in 2004, which accounts for the large rise in LTIM + STIM and NINos for that year and beyond. Whilst the rapid changes in patterns of migration in 2004 revealed some shortcomings in the IPS, which have since been addressed, the large number of NINo registrations from the EU8 have not been indicative of further large increases in the long-term migration numbers, which subsided after the initial rapid growth and appears relatively stable now.

6.2 As figure 4 shows LTIM + STIM have consistently been below the number of NINo registrations since 2006, although the pattern both data sources have followed is similar. This difference is likely to reflect visitors who may be in the country for less than one month who may need a NINo to work or use the opportunity to apply for one. It may also reflect those short-term migrants that come to accompany and join relatives and friends but are not included in the short-term estimates in this paper. They may, however, apply for NINo.

6.3 Much of the gap between LTIM and NINo registrations is likely to be driven by short-term immigration and this is supported by the NINo interactions analysis:

The NINo data from the L2 sample dataset suggest that, for the period 2010 to 2013, on average 32% of EU8 NINo registrations have interactions that are under 52 weeks, suggesting that they only stay in the United Kingdom for a short period. A further 18% of registrations state that they arrived in earlier years to the year in which they registered and therefore should not be counted as an inflow in the registration year. Although their interactions suggest visits of a short-term nature, some of these people appear to have been in the country for longer than 12 months and so a proportion may be long-term migrants.

The SPI data show, that of those EU8 nationals who registered for a NINo between 2011/12 and 2013/14, 29% had no interaction at all with the tax, national insurance or tax credits system in 2013/14 . Conversely, 71% of EU8 nationals were known to the HMRC during those tax years.

The RTI/SA data show that for those EU8 nationals registering for a NINo who arrived in 2014/15 and had interacted with RTI/SA in 2014/15, around half showed interaction with RTI for 12 months or more and 44% for less than 12 months. A further 6% showed interaction with SA. Those who had not interacted with RTI or SA records on RTI during 2014/15 could be claiming benefits, not working, or have left the country.

6.4 The analysis of NINo activity shows that a substantial proportion (up to 50%), of EU8 citizens have short-term activity of less than 12 months. This supports the evidence from the IPS that the gap between NINo activity and the LTIM series is likely to largely be accounted for by short-term migration.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. EU2

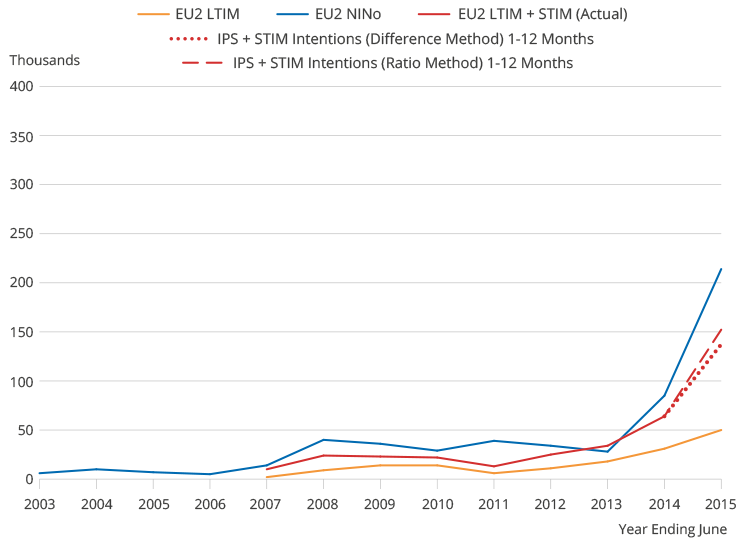

Figure 5: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU2 citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

Source: Long-term International Migration (LTIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: Short-term International Migration (STIM) - Office for National Statistics Source: National Insurance Numbers Registered to Adult Overseas Nationals - Department for Work and Pensions

Notes:

- Please see Assumptions section in Annex 1 for detail on the data used in the charts in this paper.

- Short-term migration estimates for the year to mid-2015 will be published in May 2017. However, these two provisional estimates of intended short-term migration are provided as an indication of people who arrived in this period and may have acquired a NINo. For more information, refer to Annex 1

- Note that for 2003 to 2014 the LTIM data are adjusted LTIM whereas for 2015 the data are IPS only to avoid double counting switchers who may appear in the STIM intentions data.

Download this image Figure 5: NINo Registrations for the UK, LTIM estimates of immigration to the UK, and STIM estimates of immigration to England and Wales for employment, study or work (other), EU2 citizens, mid-2003 to mid-2015

.png (32.1 kB) .xls (34.8 kB)7.1 It is the EU2 data where we see the most marked increase in NINo registrations following the lifting of employment restrictions at the start of 2014. There were similar increases in registrations for the EU8 following those countries' entry into the EU in 2004.

7.2 It is reasonable to expect that we might see some replication of this pattern for the EU2, however there are less data available as yet to help us understand whether the rise in NINo registrations is being driven by short-term migration.

7.3 We know that some of the increase in registrations will be NINos issued to people who had already arrived in the UK in previous years, for example students already in the country. DWP data show us that in 2014/15, when NINo registrations began to rise, 62% of EU2 migrants registering for a NINo had arrived in the UK more than 3 months before registering and 31% arrived more than 6 months before. This time lag effect is particularly apparent for EU2 because of the work restrictions they faced until January 2014. A proportion of those registering for a NINo in 2014 would therefore not be included in the 2014/15 LTIM figures, which is supported by the fact the LTIM / STIM data for 2013 are higher than NINo registrations for the first time. Likewise, there will be some EU2 migrants who arrived in 2014 who will be recorded in the 2015 NINo registration data. Like EU8 citizens, some of the gap seen in 2014 and 2015 is likely to reflect visitors who may be in the country for less than one month who may need a NINo to work or use the opportunity to apply for one. It may also reflect those short-term migrants that come to accompany and join relatives and friends. They are not included in the short-term estimates in this paper but may, nevertheless, apply for a NINo.

7.4 Similar to EU8 nationals, much of the gap between LTIM and NINo registrations is likely being driven by short-term immigration and this is supported by the NINo interactions analysis:

The NINo data from the L2 sample dataset suggest that, for the period 2010 to 2013, on average 23% of NINo registrations have interactions that are under 52 weeks, suggesting that they only stay in the United Kingdom for a short period. A further 38% of registrations state that they arrived in earlier years to the year in which they register and had interactions of less than 52 weeks and therefore should not be counted as an inflow in the registration year. Although their interactions suggest visits of a short-term nature, some of these people appear to have been in the country for longer than 12 months and so a proportion may be long-term migrants.

The SPI data show that, of those who registered between 2011/12 and 2013/14, over 40% of EU2 nationals had no interaction with the HMRC tax, national insurance or tax credit system in 2013/14.

The RTI/SA data tell us that for those registering for a NINo who arrived in 2014/15 and had interacted with RTI/SA, 41% showed long-term interaction with RTI, 40% short-term and 19% had interacted with SA during 2014/15. Those who had not interacted with RTI/SA could be claiming benefits, not working, or have left the country. For EU2 it is particularly difficult to unpick the latter category at this time, since many may have only applied for their NINo after January 2014 and not yet had a chance to interact with the system on a long-term basis. However the low proportion showing long-term interactions in 2014/15, once restrictions had been lifted, still indicate that a large number of new EU2 migrants have come in as short-term migrants.

7.5 The analysis of NINo activity shows that a substantial proportion (of up to 61%) for EU2 citizens have short-term activity of less than 12 months. This supports the evidence from the IPS that the gap between NINo activity and the LTIM series is likely to largely be accounted for by short-term migration.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Next steps

8.1 The analysis we have done to date and presented above indicates that the reason the LTIM estimates and the NINo figures have been diverging is likely to be largely due to short-term immigration. However the work that we have started is not complete, particularly around the interactions data. We will be undertaking further work to understand these data and hope to be able to publish further analysis in due course.

8.2 Furthermore, over the next two years, more analysis will take place to better understand what administrative sources tell us about migration patterns, particularly migrants who may enter and leave the UK several times within a year. This work should help to better understand the measurement of international migration into and out of the UK, particularly for those who are uncertain of their migration intentions and may stay for a shorter or longer time than originally stated on their arrival in the IPS. Such work will also include ONS’s ongoing investigation into how the IPS identifies particular groups of migrants, focusing on sampling, the practical operation of the survey and the methodology to produce migration estimates.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys