Cynnwys

- Introduction

- Main points

- Statistician's comment

- Things you need to know about this release

- Setting the scene

- What industry and occupations did non-UK nationals work in?

- What were the employment characteristics of foreign nationals in the UK?

- How skilled were non-UK nationals living in the UK?

- Next steps

- Annual Population Survey: Quality and methodology

- Annex 1: Sector definitions used in this article

- Annex 2: Skill level definitions

- Annex 3: Nationality groupings by country

1. Introduction

This article and accompanying data provides information on the number and characteristics of migrants in the UK Labour Market in 2016. In particular, it focuses on industry, occupation, hours worked, earnings and skills. The data accompanying the article also provides information at a regional level. This article will underpin further short articles we intend to publish over the next year looking at individual topics in greater depth.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Main points

In 2016, 11% (3.4 million +/- 0.2 million) of the UK labour market (30.3 million +/- 0.3 million) were non-UK nationals; EU nationals contributed 7% (2.2 million +/- 0.1 million) and non-EU nationals 4% (1.2 million +/- 0.1 million).

There are higher proportions of international migrants in some industry sectors more than others; particularly the 14% of the wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants workforce are international migrants (508,000 (+/- 64,000) EU nationals are employed here) and 12% of the financial and business services sector's workforce are international migrants (382,000 (+/- 56,000) of which are EU nationals); 8% of workers in manufacturing are EU8 nationals.

701,000 non-UK nationals work in the public administration, education and health sector; over a quarter of EU14 workers (27%) and non-EU workers (29%) are employed in these industries.

The highest number of non-UK nationals are employed in elementary occupations (such as selling goods, cleaning or freight handling), in which approximately 669,000 (+/-86,000) non-UK nationals are employed (510,000 are EU nationals); this is followed by professional occupations, in which an estimated 658,000 (+/-83,000) non-UK nationals were employed (352,000 were EU nationals).

Non-UK nationals are more likely to be in jobs they are over-qualified for than UK nationals; approximately 15% of UK nationals were employed in jobs they were deemed to be over-educated for (in comparison to other workers), compared with almost 2 in 5 non-UK nationals (37% of EU14, EU2 and non-EU nationals and 40% of EU8 nationals).

EU2 and EU8 work more hours than UK nationals; half of working EU8 nationals (50%) and nearly two-thirds of EU2 nationals (61%) work more than 40 hours per week, compared to a third of UK nationals (32%).

Compared to the national average (median) earnings (£11.30 per hour), EU14 nationals earned more (£12.59) whereas EU8 and EU2 had the lowest (£8.33).

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Statistician's comment

“Today’s analysis shows the significant impact international migration has on the UK labour market. It is particularly important to the wholesale and retail, hospitality, and public administration and health sectors, which employ around 1.5 million non-UK nationals.

“Migrants from Eastern Europe, Bulgaria and Romania are likely to work more hours and earn lower wages than other workers, partly reflecting their numbers in lower-skilled jobs. Many EU migrants are also more likely to be over-educated for the jobs they are in."

Anna Bodey, Migration Analysis, Office for National Statistics.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Things you need to know about this release

This article considers international residents based on their nationality rather than their country of birth, following recommendations supplied to the Lords EU Home Affairs Sub-Committee1.

A non-UK national is an individual who resides in the UK but is currently a citizen of another country; this characteristic is referred to as their nationality.

It should be noted that a person’s nationality can change over time. For instance, a person may come to the UK as an overseas national, but later apply for British citizenship. (Information on grants of citizenship by previous nationality is published by the Home Office2). Some non-UK nationals may have been born in the UK, such as children of overseas nationals.

The European Union (EU) is a political and economic union of 28 member states. Not all member states joined the union at the same time, which has led to countries being split into the smaller sub-groups: EU14, EU8, EU2 and EU other.

This article compares characteristics of the following nationality groups:

- UK

- EU143

- EU84

- EU25

- EU other6

- non-EU

Data quality

Numbers presented in this article are estimates based on the UK household population only. As these are estimates, confidence intervals have been included to provide a measure of the margin of error for these estimates.

A confidence interval is the range within which the true value lies with known probability. For example, a 95% confidence interval represents the range in which, over many repeats of the sample under the same conditions, we would expect the confidence interval to contain the true value to lie 95 times out of 100. The uppermost and lowermost values of the confidence interval are termed "confidence limits".

The formula used to calculate this is contained in the data tables.

Data used in this analysis: Annual Population Survey

The analysis is largely based on the Annual Population Survey (APS) Jan to Dec 2016. The analysis also draws from data available in the APS 3-year pooled dataset Jan 2013 to Dec 2015 (the most recent available); this dataset provides a larger sample on which to conduct analysis, which allows more detailed analysis to be undertaken. This is a household survey.

Things to be aware of concerning the APS:

- a person’s nationality is self-reported and is influenced by how a person perceives their nationality

- the survey is designed to measure household population stocks within the UK7; it does not measure the flow of non-UK nationals into and out of the UK8

- data is collected from individuals in households, but does not include most communal establishments (managed accommodation such as halls of residence, hostels and care homes); this means that students living in communal establishments will only be included in APS estimates if their parents (resident in a household) are sampled and include the absent student

- students living in non-communal establishments will be captured in APS sampling

- the APS will include long-term migrants and some short-term migrants although it is unlikely to include short-term migrants living in the UK for very short periods of time

This could have a disproportionate effect on certain categories of overseas nationals. For example, students and short-term or seasonal workers from overseas (such as those working in the agricultural industry) may be more likely to stay in communal establishments or be in the UK on a short-term basis and will therefore be excluded from the sample, resulting in their under-representation.

Things to be aware of concerning the APS 3-year pooled dataset Jan 2013 to Dec 2015:

- it is less sensitive to more volatile trends than 1-year datasets as this dataset encompasses 3 years

- changes to those eligible to travel to the UK from EU countries during the 2013 to 2015 period would not be specifically noted (that is, it does not specifically highlight the lifting of employment restrictions on nationals of Bulgaria and Romania in January 20149, which had been in place since both joined the EU in 2007, nor the joining of Croatia to the EU in July 2013)

Data has not been used from the International Passenger Survey (IPS) as this survey is a measure of the flows into and out of the UK, whereas the APS provides a better snapshot of the long-term household overseas population. More information can be found in a report published in December 2016, titled Note on the differences between Long-Term International Migration flows derived from the International Passenger Survey and estimates of the population obtained from the Annual Population Survey: December 2016. The most recent IPS estimates on flows were published on 23 February 2017 in the Migration Statistics Quarterly Report.

Information contained in the data tables

The data tables contain the data analysed in the article at a UK level and additional data at a regional level.

Policy and operational context

Immigration control operates differently for EU nationals exercising treaty rights and non-European Economic Area (non-EEA) nationals who, for example, generally require entry clearance visas and employers sponsoring them to enter the UK for skilled work. Further information about the operation of the “points-based system” for non-EEA nationals can be found in the Home Office’s user guide to its Immigration Statistics. Information on policy changes relating to immigration control for work routes are produced by the Home Office and can be found in Policy and legislative changes affecting migration to the UK: timeline.

Notes for: Things you need to know about this release

- Evidence provided by ONS to the Lords EU Home Affairs Sub-Committee on 15 December 2015 states: “In many cases therefore, nationality is the preferable measure to use when seeking to understand the interactions of migrants with, for example the labour market, the benefit system, housing, education and health. With such a large proportion of those who are born abroad having now acquired British nationality it is not recommended that country of birth be used as a headline measure in analysis of such data.”

- The latest edition is available in the Immigration Statistics Citizenship publication.

- EU14 are countries who were members of the EU prior to 2004: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland (Republic of), Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden.

- EU8 are countries who joined the EU January 2004: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia.

- EU2 is Bulgaria and Romania, who joined the EU in January 2007

- EU other contains Cyprus, Malta (both joined January 2004) and Croatia (joined July 2013)

- Resident population stocks refer to the number of people living in the UK.

- Flow of non-UK nationals refers to the number of people entering and leaving the UK.

- More information about the employment restrictions placed on Bulgarian and Romanian nationals is available in a report by the House of Commons Library, titled Ending of transitional restrictions for Bulgarian and Romanian workers.

5. Setting the scene

In 2016, the resident household population of the UK was estimated to be 64.7 million1 (+/-0.4 million). Table 1 shows how the household population has changed between 2011 and 2016. It shows that the estimate of EU2 nationals resident in the UK has increased by an estimated 273,000 between 2011 and 2016; this is likely due to the lifting of employment restrictions from Romanian and Bulgarian nationals in 2014. Otherwise, although the numbers have increased, the proportion of UK residents by nationality group has largely remained the same.

Table 1: UK resident population by nationality, 2011 and 2016

| 2011 | 2016 | |||

| Estimate | % | Estimate | % | |

| ( +/- ) | ( +/- ) | |||

| UK | 57,288 | 92 | 58,720 | 91 |

| (+/- 333) | (+/- 357) | |||

| EU14 | 1,110 | 2 | 1,557 | 2 |

| (+/-51) | (+/- 65) | |||

| EU8 | 1,060 | 2 | 1,567 | 2 |

| (+/- 49) | (+/- 62) | |||

| EU2 | 141 | 0~ | 414 | 1 |

| (+/- 21) | (+/- 35) | |||

| EU-other | 17 | 0~ | 28 | 0~ |

| (+/- 6) | (+/- 8) | |||

| Non-EU | 2,539 | 4 | 2,425 | 4 |

| (+/- 78) | (+/- 81) | |||

| Total | 62,480 | 100 | 64,730 | 100 |

| (+/- 349) | (+/- 378) | |||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Estimates are rounded to the nearest thousand. Totals may not sum due to rounding. | ||||

| 2. 0~ indicates that a percentage has been rounded to 0, i.e. is less than 0.5%. It is not a true zero. | ||||

| 3. These population estimates are likely to differ from the mid-year population estimates, scheduled to be published in June 2017, as they do not include communal establishments. | ||||

| 4. Previously published 2011 estimates differ to these due to different countries classified within each nationality grouping. Please see Annex 3 for the country groupings used in this article. | ||||

Download this table Table 1: UK resident population by nationality, 2011 and 2016

.xls (30.2 kB)In 2016, within the UK, the household population aged 16 to 64 was estimated to be 41.0 million2 (+/-0.3 million).

Figure 1 shows that working immigrants tend to be younger than UK workers. More than half (estimated 53%) of non-UK working nationals aged 16 to 64 years old were between 25 and 39 years old.

Figure 1: Comparison of the age distribution of UK and non-UK nationals in employment aged 16 to 64 years old

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Totals may not sum due to rounding.

- 13 April 2017: title amended to include "in employment".

Download this chart Figure 1: Comparison of the age distribution of UK and non-UK nationals in employment aged 16 to 64 years old

Image .csv .xlsThe data tables behind this release contain the estimates of the number and proportion of UK residents in each age band by detailed nationality group (UK, EU14, EU8, EU2, EU-other, non-EU).

Table 2 illustrates the percentage of employed, unemployed and economically inactive UK residents by nationality group. The proportion of those in employment was highest for EU8 and EU2 nationals (estimated 83%) whilst non-EU nationals had the lowest proportion of people in employment (estimated 62%); this reflects the fact that many non-EU nationals immigrate to study. Approximately three-quarters of nationals from the UK and EU14 countries were in employment (estimated 74% and 76% respectively). Slightly more than 1 in 10 (estimated 11%) of non-EU nationals stated study as the reason for their inactivity, which was the highest proportion compared with other nationalities. Non-EU nationals were estimated to also have had a higher proportion of residents who are inactive for other reasons, compared with the national average (estimated 22% compared with national average of 16%).

Table 2: Number and percentage of UK 16 to 64 aged population by nationality and economic activity, UK, 2016

| (thousands) | ||||||||||

| In employment | Unemployed | Inactive: student | Inactive: other | Total | ||||||

| Estimate | % | Estimate | % | Estimate | % | Estimate | % | Estimate | % | |

| ( +/- ) | ( +/- ) | ( +/- ) | ( +/- ) | ( +/- ) | ||||||

| UK | 26,915 | 74 | 1,385 | 4 | 2,024 | 6 | 5,998 | 17 | 36,322 | 100 |

| (+/- 253) | (+/- 58) | (+/-72) | (+/-112) | (+/- 291) | ||||||

| EU14 | 863 | 76 | 47 | 4 | 100 | 3 | 132 | 12 | 1,142 | 100 |

| (+/- 50) | (+/- 12) | (+/-18) | (+/-18) | (+/- 57) | ||||||

| EU8 | 1,015 | 83 | 42 | 3 | 51 | 4 | 121 | 10 | 1,229 | 100 |

| (+/-52) | (+/-10) | (+/-11) | (+/-17) | (+/- 56) | ||||||

| EU2 | 281 | 83 | 13 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 35 | 10 | 340 | 100 |

| (+/-30) | (+/- 6) | (+/- 6) | (+/- 10) | (+/- 33) | ||||||

| EU Other | 18 | 74 | c | c | c | c | c | c | 22 | 100 |

| (+/- 7) | (+/- 8) | |||||||||

| Non-EU | 1,206 | 62 | 101 | 5 | 211 | 11 | 437 | 22 | 1,955 | 100 |

| (+/- 59) | (+/- 17) | (+/- 26) | (+/- 33) | (+/- 74) | ||||||

| Total | 30,299 | 74 | 1,588 | 4 | 2398 | 6 | 6734 | 16 | 41,020 | 100 |

| (+/- 271) | (+/- 63) | (+/-79) | (+/-120) | (+/- 312) | ||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||

| 1. Estimates are rounded to the nearest thousand. Totals may not sum due to rounding. | ||||||||||

| 2. The percentages contained in this table are not employment and unemployment rates. | ||||||||||

| 3. 'c' indicates that data is not available due to disclosure control. | ||||||||||

| 4. 'Inactive: other' includes inactivity for reasons such as retirement, illness, disability and looking after family. | ||||||||||

Download this table Table 2: Number and percentage of UK 16 to 64 aged population by nationality and economic activity, UK, 2016

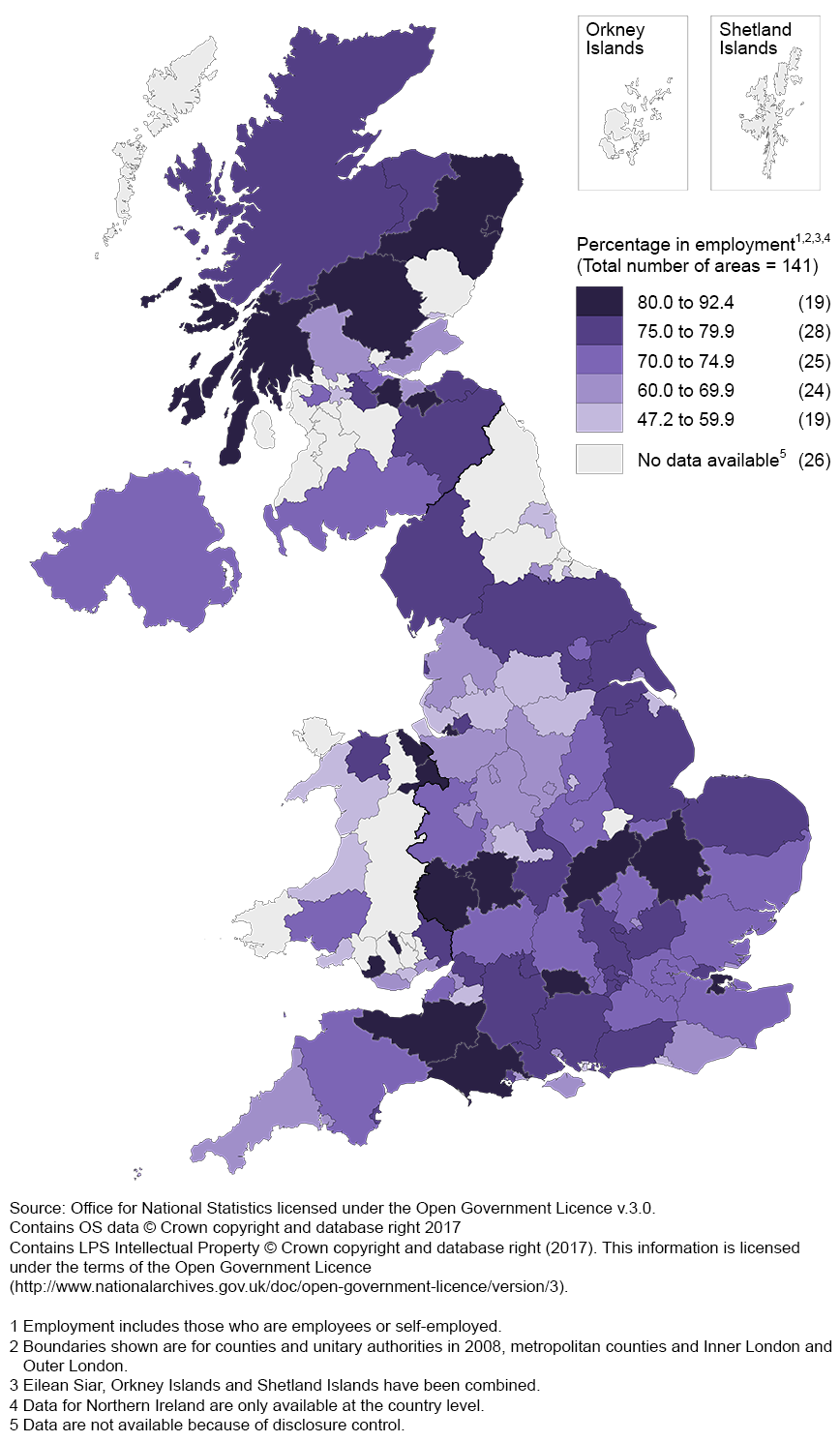

.xls (31.2 kB)Figure 2 shows the percentage of non-UK nationals aged 16 to 64 years who were employed within the borders of a specific county or unitary authority in 2016. The percentage of non-UK nationals aged 16 to 64 years in employment in the whole of the UK was estimated to be 69%. Figure 2 shows that the majority of areas in the south of England were estimated to have a higher than average percentage of non-UK nationals in employment.

Figure 2: Percentage of 16-64 year old non-UK nationals in employment by county and unitary authority

UK, 2013 to 2015

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 2: Percentage of 16-64 year old non-UK nationals in employment by county and unitary authority

.png (367.6 kB) .xls (52.2 kB)The remainder of this article focuses on those aged 16 to 64 in the UK resident household population who describe themselves as being in employment.

Notes for: Setting the scene

1 and 2. Annual Population Survey 2016

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. What industry and occupations did non-UK nationals work in?

This section presents an analysis of the following characteristics against a worker’s nationality:

- sector of main job

- occupation of main job

The industry groupings presented are based on standard classifications, so present a broad picture. Within these classifications, there are likely to be further differences in the numbers of workers by nationality, which will be addressed in future analyses (See Next Steps).

Industry sector of workers

In 2016, the UK labour market was estimated to comprise 89% UK nationals and 11% non-UK nationals.

Figure 3 shows that within the energy and water and public admin, education and health sectors that more than 9 in 10 employed workers were UK nationals. EU2 nationals made up approximately 3% of the UK labour market; however, they represented approximately 8% of workers in manufacturing. Despite that almost 3 in 10 (estimated 27%) EU14 nationals worked in the public admin, education and health sector, they only contributed approximately 2% of the workforce.

In numerical terms, the sector with the highest number of non-UK nationals employed is the wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants sector, in which approximately 761,000 (+/-96,000) non-UK nationals are employed, followed by the public admin, education and health sector, in which an estimated 701,000 (+/-85,000) non-UK nationals were employed. The highest number of EU nationals were also employed in the wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants sector (estimated 508,000 +/-69,000), followed by financial and business services (approximately 382,000 +/-59,000).

Figure 3: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by industry sector

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 3: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by industry sector

Image .csv .xlsThese proportions will not reflect the full impact of additional short-term foreign workers in these sectors. For reasons outlined in the Things you need to know about this release section, short-term migrants are likely to be under-represented in the Annual Population Survey (APS); this affects some sectors more than others.

One sector that is likely to be under-represented is agriculture, forestry and fishing. There are a range of surveys that are able to capture aspects of the workforce in the agriculture industry, for example:

- June Agriculture Survey (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs)

- Labour Providers Survey (National Farmers Union)

- Annual Population Survey and Labour Force Survey (Office for National Statistics)

But, none of these surveys are designed to capture the total number of long- and short-term (seasonal) workers in the agriculture industry by nationality.

Figure 4 shows that, in 2016, the highest proportion of UK, EU14 and non-EU nationals worked in the public admin, education and health sector (estimated 31%, 26% and 28%) respectively. The highest proportion of resident EU8 nationals (estimated 26%) worked in the wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants sector; 22% of EU8 nationals were estimated employed in the manufacturing sector.

These proportions reflect the sector in which people work rather than the type of job, for example, people working in the finance sector may include cleaning and administrative staff as well as finance professionals, and the same is true for other sectors.

Figure 4: Distribution of workers in each sector by nationality group

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

- Totals may not sum to 100% due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 4: Distribution of workers in each sector by nationality group

Image .csv .xlsOccupation of workers

Figure 5 shows the proportion of workers in each nationality group by occupation. 89% of workers are UK nationals and 11% are non-UK nationals. Approximately 21% of workers in elementary (such as selling goods, cleaning or freight handling) and process, plant and machine operatives occupations were non-UK nationals. The proportion of non-UK nationals in managers, directors and senior officials, associate professional and technical occupations, administrative and secretarial occupations, and sales and customer service occupations was lower than the occupation average across all professions.

In numerical terms, the highest number of non-UK nationals are employed in elementary occupations, in which approximately 669,000 (+/-86,000) non-UK nationals were employed, followed by professional occupations, in which an estimated 658,000 (+/-83,000) non-UK nationals were employed. This was the same for EU nationals, with 510,000 (+/-65,000) and 352,000 (+/-53,000) respectively employed in those occupations.

Figure 5: Distribution of workers in each occupation by nationality group

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 5: Distribution of workers in each occupation by nationality group

Image .csv .xlsFigure 6 shows that UK, EU14 and non-EU nationals were most likely to work in professional occupations (estimated 21%, 30% and 26% respectively). EU8 nationals were most likely to work in lower-skilled occupations; approximately half (51%) of EU8 nationals who worked in the UK were employed in the process, plant and machine operatives or elementary occupations. Almost one-third (estimated 31%) of EU2 nationals worked in elementary occupations.

The lowest proportion of both EU8 and EU2 nationals worked as managers, directors and senior officials (estimated 3% and 4% respectively). This does not necessarily mean that EU8 and EU2 nationals have a lower professional skill level than workers from other countries. EU8 and EU2 nationals may choose to work in lower-skilled roles to improve other skills, such as their English language skills, before moving on to more skilled labour.

Figure 6: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by occupation

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 6: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by occupation

Image .csv .xls7. What were the employment characteristics of foreign nationals in the UK?

This section presents the following characteristics of workers in the UK labour market:

- whether workers were employed in the public or private sector

- the proportion of workers who were self-employed

- whether workers were full or part-time

- the hours worked by those in employment

- the median hourly pay

Public or private sector

Figure 7 illustrates how, regardless of nationality, a higher proportion of people worked in the private sector compared with the public sector in 2016. Approximately 5% of EU8 and EU2 nationals worked in the public sector compared with around 20% of UK, EU14 and non-EU nationals.

Figure 7: Distribution of workers in each nationality group in the public and private sector

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 7: Distribution of workers in each nationality group in the public and private sector

Image .csv .xlsIt should be noted that there are nationality restrictions on some public sector roles that may prevent a non-UK national from working in such a role. For example, only nationals from the UK, the Republic of Ireland, the Commonwealth, the European Economic Area (EEA), Switzerland and Turkey are eligible for employment in the UK Civil Service1. Exceptions to this rule do exist, however.

There were an estimated 6.7 million (+/-0.1 million) workers employed in the public sector in 2016, according to the APS. This is higher than the estimate published in the Public sector employment, UK: September 2016 statistical bulletin, which estimates that in September 2016 total UK public sector employment was 5.4 million; however, these figures do not provide a breakdown by nationality. It should be noted that public sector estimates in the Annual Population Survey (APS) are self-reported. This means that survey respondents classify themselves as public or private sector workers, which does not necessarily correspond to the national accounts definition used for public sector employment estimates2. This is because, for example, if an individual is a caterer in a hospital, then their work environment could be described as public sector, whereas they could actually be employed by a private company and contracted to work in the hospital.

Self-employed

Overall, 14% of those in employment within the UK were self-employed. Figure 8 below compares the proportions of self employment by nationality. It illustrates that EU2 nationals living in the UK in 2016 had the highest proportion of 16- to 64-year-olds who were self-employed (estimated 25%), whilst UK nationals had the lowest proportion of those self-employed alongside EU14 nationals (estimated 14%).

Figure 8: Distribution of workers in each nationality group who are employees and self-employed

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

- The percentage of unpaid family workers and employees on government schemes rounded to 0%.

Download this chart Figure 8: Distribution of workers in each nationality group who are employees and self-employed

Image .csv .xlsThe APS 2016 provides limited information on the sectors in which self-employed persons work, due to small sample sizes.

Figure 9, therefore, displays estimates produced using the APS 3-year pooled dataset Jan 2013 to Dec 2015, which can provide more detailed information due to the larger sample sizes.

It shows the proportion of self-employed workers by the industry sector they worked in. Almost half of (48%) EU2 nationals were self-employed in the 'Construction' sector. A higher than average proportion of non-EU nationals was found to work in the 'Wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants' sector (estimated 19% to 12%). Almost 1 in 3 (estimated 30%) EU14 nationals were self-employed in 'Financial and business services', compared with an average of approximately 23%.

Figure 9: Distribution of the self-employed in each nationality group by sector

UK, 2013 to 2015

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

- Totals may not sum to 100% due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 9: Distribution of the self-employed in each nationality group by sector

Image .csv .xlsWorking pattern

In 2016, 75% of those in employment worked full-time. The proportion of EU8 and EU2 nationals who were full time workers is estimated to be more than 4 in 5 (estimated 82% and 88% respectively).

Figure 10 shows that the higher proportion of full-time EU8 nationals was due to a slightly higher proportion of EU8 males who worked full-time. This pattern was mirrored when looking at females; more EU8 female nationals worked full-time compared to the national average. Male non-EU nationals had the highest proportion of workers who were part-time.

Figure 10: Distribution of workers within each sex and working full- or part-time by nationality group

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

- The columns corresponding to each nationality sum to 100%.

Download this chart Figure 10: Distribution of workers within each sex and working full- or part-time by nationality group

Image .csv .xlsThe highest proportion of full- and part-time UK nationals were employed in the public admin, education and health sector. Female UK nationals contributed almost half of the public admin, education and health sector workforce (estimated 46%); however, the highest proportion of male workers from the UK were employed in the financial and business services sector (estimated 18%). EU14 workers shared the same pattern, with the highest proportion of female workers being in the public admin, education and health’ sector (estimated 39%), whilst the highest proportion of male workers from EU14 countries were employed in the financial and business services sector (estimated 26%).

The highest number (107,000 +/-19,000) of male EU14 nationals worked in the financial and business services sector if working full-time, yet were more likely to work in the wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants sector (22,000 +/-8,000) if working part-time. The highest proportion of non-EU nationals worked in the public admin, education and health sector (250,000 +/-26,000) if working full-time, and worked in the wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants and the public admin, education and health sector (98,000 +/-16,000 and 89,000 +/-15,000 respectively) if working part-time.

This data is available for all sectors in the data behind the release.

Hours worked

Figure 11 shows that at least half of EU8 and EU2 workers (estimated 50% and 61% respectively) worked more than 40 hours per week compared with around a third of UK nationals (estimated 32%). On average, 1 in 5 UK and non-EU residents worked below 25 hours per week (estimated 20%); however, a smaller proportion of resident EU nationals (regardless of country grouping) worked below 25 hours a week.

Figure 11: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by hours worked

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

- Hours worked refers to the total usual hours worked in a week, excluding overtime.

Download this chart Figure 11: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by hours worked

Image .csv .xlsHourly pay

When comparing the average gross hourly pay3 by nationality, the median is chosen as the main measure; that is the data value at which 50% of data values are above it and 50% of data values are below it. We present the median because the distribution of earnings is not symmetrical, with more people earning lower salaries than higher salaries; this is consistent with our other publications, such as the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), our preferred measure of earnings.

The hourly pay estimates collected in the Annual Population Survey (APS) are self-reported and have the potential to be incorrectly estimated by respondents. ASHE collects information directly from a business’s payroll and is deemed to be more accurate, but it does not collect information on an employee’s nationality. Therefore, as no other source is currently available, the hourly pay by nationality group estimates from the APS are presented here.

When comparing the analysis for all UK employees (of all nationalities), the differing methods used to produce earnings data result in a different median wage being produced. For example, in 2016, a median wage of £12.10 is estimated using ASHE data whilst the APS estimate of median wage stands at £11.30 (both estimates exclude overtime).

Please also note that self-employed persons, (approximately 14% of UK residents aged 16- to 64-years-old), are not included4; this measure is collected for employees and those in government training programmes only. Please see the Next steps section for more information on how we plan to develop these estimates in the future.

Figure 12 shows that EU14 nationals received the highest median hourly pay at £12.59 compared with the national average of £11.30; this can be explained by the fact that almost 2 in 5 (37%) of EU14 nationals were employed in high-skilled jobs, the highest proportion in comparison to other nationals (please see the Skills section for more detail). This is followed by UK nationals who received £11.53 per hour, non-EU nationals with £10.97 per hour and £9.35 for nationals from Cyprus, Malta and Croatia. EU8 and EU2 workers received the lowest median hourly pay, compared with all other workers, receiving £8.33; again a possible explanation for this is that EU8 and EU2 nationals have a higher proportion of workers in low-skilled jobs (please see the Skills section for more detail).

Figure 12: Median gross hourly pay of workers by nationality group

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Hourly pay may include overtime and any bonuses received.

Download this chart Figure 12: Median gross hourly pay of workers by nationality group

Image .csv .xlsNotes for: What were the employment characteristics of foreign nationals in the UK?

- As stated in the Civil Service Nationality Rules: Guidance on checking eligibility.

- Definition stated in A Brief Guide to Sources of Public Sector Employment Statistics.

- Gross hourly pay is the amount of pay received per hour before tax, National Insurance and other deductions.

- Self-employed workers are not included due to difficulties in obtaining accurate information without complex questioning. This is because self-employed workers do not necessarily receive a salary and may receive payment in ways other than money.

8. How skilled were non-UK nationals living in the UK?

This section presents the skill level of working UK residents in three ways. These are:

- by highest qualification level achieved

- by the skill level of their occupation

- by whether a worker had an education level that is “matched” to their occupation, or whether they were over- or under-educated

The Home Office published analysis in 2014 on the skill level of workers in the UK labour market over a 10-year period (ending 2012). This release is available to read at Employment and occupational skill levels among UK and foreign nationals.

The highest qualification achieved

The Annual Population Survey provides information on the highest qualification level a person has achieved. It should be noted that the highest qualification achieved does not define whether a person can work in a job requiring that level qualification. For example, a person may have one GCSE at A* to C, however, usually a job at Level 2 would require five GCSEs of A* to C. A worker may also have relevant experience that negates the need for a higher qualification level. It also does not tell us whether a person was working in a job that was appropriate for their education level.

When looking into the highest qualification achieved by nationality, the following was found:

- more than half of EU14 nationals (estimated 57%) had a degree or equivalent qualification, similar to non-EU nationals (estimated 52%)

- approximately one-third of UK nationals had a degree or equivalent (estimated 33%)

- Almost one-quarter (estimated 24%) of EU8 nationals had a degree or equivalent; the lowest proportion compared with all other nationalities

There were a high proportion of non-UK nationals who stated their highest qualification is an ”other qualification”. When interpreting this result, it should also be noted that foreign qualifications can be difficult to capture within the survey, and a person with a foreign qualification, other than a degree or equivalent, is often classified as having an “other qualification”.

Skill level of occupation

Occupations can be aggregated to four groups and these groupings represent the skill level of the job, rather than the person. These classifications are as follows:

- high (for example, chief executives, teacher, engineer)

- upper middle (for example, accommodation managers, electrician)

- lower middle (for example, administrator, childminder, hairdresser)

- low (for example, farm worker, cleaner, waiters or waitresses)

Please see Annex 2 for more information on these groupings and the occupations contained within them.

Figure 13 shows that almost 2 in 5 EU14 nationals (estimated 37%) were employed in high-skill jobs; this compares with almost 1 in 10 (estimated 8%) EU8 nationals. The chart also shows that an estimated 69% of EU8 nationals and 61% of EU2 nationals were employed in low- or lower-middle skilled jobs, in comparison to less than 50% of nationals from the UK, EU14 and outside the EU.

Figure 13: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by skill level of occupation

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 13: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by skill level of occupation

Image .csv .xlsSkills mismatch and education attainment

Determining the skills mismatch1 of a worker and their job enables comparison between a worker’s highest qualification and the average level of qualification held by those in the job. This looks to determine whether a worker2 is:

- matched

- over-educated

- under-educated

This measure is based on a methodology we have previously produced. For further information on the methodology of this measure, please see the original article titled Analysis of the UK labour market - estimates of skills mismatch using measures of over and under education: 2015.

Figure 14 shows the proportion of workers, by nationality, who were over-educated, under-educated or whose education level matched their job role. The graph shows that across all nationalities, the majority of workers had the appropriate skill level for their work. Looking at the specific nationality groupings, UK nationals were equally likely to be under- or over-educated whereas this wasn’t true for non-UK nationals. More than 1 in 3 non-UK nationals (regardless of country grouping) were estimated to be over-educated compared with other workers; approximately 1 in 2 were estimated to be matched and around 1 in 10 under-educated.

As previously shown, many foreign workers were young and well-educated. One explanation for the proportion classed as over-educated is that they may have sought employment in the UK to do lower-skilled jobs in order to experience life in the UK and gain other experiences (such as learning English), rather than as a career move.

Figure 14: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by whether they are matched, over-educated or under-educated for their job

UK, 2016

Source: Annual Population Survey, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Data is unavailable for EU other nationals due to disclosure controls.

Download this chart Figure 14: Distribution of workers in each nationality group by whether they are matched, over-educated or under-educated for their job

Image .csv .xlsThis measure is also explored by industry sector and the data are contained in the data tables.

Notes for: How skilled were non-UK nationals living in the UK?

- Defined by previous ONS methodology as the comparison of how far educational attainment of groups within the UK workforce differs from the average education level for their occupations.

- Matched are individuals in employment whose highest level of educational attainment lies within one standard deviation of the mean for their given occupation. Over-educated have a highest educational attainment greater that one standard deviation below the mean. Under-educated have a highest educational attainment greater than one standard deviation above the mean.

9. Next steps

This article, by its very nature, has provided a high level overview of migration and the UK labour market. It will underpin further shorter articles that will provide more in-depth coverage of the topics discussed. In particular, these shorter articles will also provide a regional angle. We are also planning to release further articles analysing the activity of non-UK nationals who are resident in the UK, starting with housing in May 2017.

The article has highlighted several areas where more information is available for the UK as a whole but where these other sources cannot be broken down by nationality. The following sections highlight where more analysis can be done to improve the evidence base.

Current data sources

The Annual Population Survey (APS) provides information on the activity of migrants in the labour market at a UK level (for example, the industry sectors they work in). When exploring this topic by region, not all data are available. There is a growing requirement for these data to be available at a local level, which current data sources are not designed for.

Future data sources

The use and linkage of administrative data will enable us to provide much more detailed analysis at smaller, more local levels of geography. Linked data could provide information that may be able to fill the information gaps, for example:

- sectors with a high number of short-term migrants employed

- income of non-UK nationals at a local level (for both employees and self-employed)

- industry and occupation of workers at a local level

- tax contributions at a local level

- benefits received at a local level

- more robust estimates of hourly wages of EU and non-EU migrant workers

Possible data sources that may provide additional information are administrative data held by other government departments, for example the Department for Work and Pensions and Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, linked with the Migrant Worker Scan1.

It is possible that access to these data sources will enable us to produce statistics with detailed breakdowns at a more local level, which are meaningful and add further insight. However, it should not be assumed that data sources collected for one purpose will necessarily be suitable for other purposes.

More information

International migration data and analysis: Improving the evidence, released on 23 February 2017, highlighted the development plans for international migration statistics. This article covers development areas for both the stocks (the activity of migrants currently in the UK) and the flows of migration (the activity of migrants entering and leaving the UK).

This article covers the information that is currently available about non-UK nationals’ activity in the UK labour market and highlights the data gaps. It highlights the partial information we have available on the industry and occupation sectors that foreign nationals are employed in, information on their earnings and information regarding the self-employed. These areas are the main focus of development for statistics relating to the activity of residents in the UK labour market.

Notes for: Next steps

- The Migrant Worker Scan (MWS) contains information on all overseas nationals who have registered for and been allocated a National Insurance Number (NINo).More information can be found in Quality Assurance for Administrative Data (QAAD) document for the Migrant Worker Scan, published in January 2017.

10. Annual Population Survey: Quality and methodology

The Quality and Methodology Information document contains important information on:

- the strengths and limitations of the data and how it compares with related data

- uses and users of the data

- how the output was created

- the quality of the output including the accuracy of the data

11. Annex 1: Sector definitions used in this article

This article uses the Standard Industrial Classifications 2007 (UK SIC 2007) to define an industry or sector (group of industries). These are used to classify business establishments and units by the type of activity in which they are engaged. For more information, please view UK SIC 2007.

In the Annual Population Survey, an interviewer asks a respondent what their firm mainly make or do. From the answer, the interviewer determines the UK SIC 2007 code of their job. The industries used throughout this article are defined in Table 3.

Table 3: Industries contained within each sector

| Sector | Industries included | |||||||

| A | Agriculture | A | Agriculture, forestry and fishing | |||||

| B, D, E | Energy and water | B | Mining and quarrying | |||||

| D | Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | |||||||

| E | Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | |||||||

| C | Manufacturing | C | Manufacturing | |||||

| F | Construction | F | Construction | |||||

| G, I | Wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants | G | Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | |||||

| I | Accommodation and food service activities | |||||||

| H, J | Transport and communication | H | Transportation and storage | |||||

| J | Information and communication | |||||||

| K, L, M, N | Financial and business services | K | Financial and insurance activities | |||||

| L | Real estate activities | |||||||

| M | Professional, scientific and technical activities | |||||||

| N | Administrative and support service activities | |||||||

| O, P, Q | Public admin, education and health | O | Public administration and defence; compulsory social security | |||||

| P | Education | |||||||

| Q | Human health and social work activities | |||||||

| R, S, T, U | Other services | R | Arts, entertainment and recreation | |||||

| S | Other service activities | |||||||

| T | Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods-and services-producing activities of households for own use | |||||||

| U | Activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies | |||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||||

Download this table Table 3: Industries contained within each sector

.xls (30.2 kB)12. Annex 2: Skill level definitions

This article uses the Standard Occupational Classifications 2010 (SOC 2010) to define an industry or sector (group of industries). These are used to classify business establishments and units by the type of activity in which they are engaged. For more information, please view SOC 2010.

In the Annual Population Survey, an interviewer asks a respondent what their main job was in the week prior to the interview and what they mainly did in that job. From the answer, the interviewer determines the SOC 2010 code of their role.

Skill level is derived from grouping the SOC 2010 codes, which have been grouped into the skill levels associated with the occupation. Table 4 contains the groupings of SOC 2010 codes that form each skill level.

Table 4: Occupations contained within each skill level

| Skill level | Standard Occupational Classifications 2010 included | |

| High | 11 | Corporate managers and directors |

| 21 | Science, research, engineering and technology professionals | |

| 22 | Health professionals | |

| 23 | Teaching and educational professionals | |

| 24 | Business, media and public service professionals | |

| Upper middle | 12 | Other managers and proprietors |

| 31 | Science, research, engineering and technology associate professionals | |

| 32 | Health and social care associate professionals | |

| 33 | Protective service occupations | |

| 34 | Culture, media and sports occupations | |

| 35 | Business and public service associate professionals | |

| 51 | Skilled agricultural and related trades | |

| 52 | Skilled metal, electrical and electronic trades | |

| 53 | Skilled construction and building trades | |

| 54 | Textiles, printing and other skilled trades | |

| Lower middle | 41 | Administrative occupations |

| 42 | Secretarial and related occupations | |

| 61 | Caring personal service occupations | |

| 62 | Leisure, travel and related personal service occupations | |

| 71 | Sales occupations | |

| 72 | Customer service occupations | |

| 81 | Process, plant and machine operatives | |

| 82 | Transport and mobile machine drivers and operatives | |

| Low | 91 | Elementary trades and related occupations |

| 92 | Elementary administration and service occupations | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||

Download this table Table 4: Occupations contained within each skill level

.xls (28.2 kB)13. Annex 3: Nationality groupings by country

Table 5 displays the countries included in each nationality grouping used within this article. This is consistent with the nationality groupings used in our labour market releases.

Table 5: Countries contained within each nationality group

| Nationality group | Countries included |

| United Kingdom | United Kingdom |

| European Union 14 | Austria |

| Belgium | |

| Denmark | |

| Finland | |

| France | |

| Germany | |

| Greece | |

| Italy | |

| Luxembourg | |

| Netherlands | |

| Portugal | |

| Spain (except Canary Islands) | |

| Spain (not otherwise specified) | |

| Sweden | |

| Canary Islands | |

| Monaco | |

| Vatican City | |

| Republic of Ireland | |

| European Union 8 | Czech Repblic |

| Estonia | |

| Hungary | |

| Latvia | |

| Lithuania | |

| Poland | |

| Slovakia | |

| Slovenia | |

| Czechoslovakia (not otherwise specified) | |

| European Union 2 | Bulgaria |

| Romania | |

| European Union - other | Croatia |

| Cyprus | |

| Malta | |

| Non-EU | Countries not classified elsewhere |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |