1. About this article

This article updates on our progress towards developing a better understanding on student migration to and from the UK since the November 2016 update.

We published two papers1 in 2016 that described what the statistics show on international student migration and potential reasons for the difference between long-term immigration of international students and those who subsequently emigrate after their studies. In addition, we published a paper2 in February 2017 on wider plans to make better use of data sources across government to inform public and policy debate on international migration, including international student migration.

ONS and other government departments are working together on a continuing programme of research to better understand what international students do after their studies and this article provides an update on progress made since the last published update in November 2016.

Latest provisional figures3 show that in the year ending September 2016:

long-term immigration to the UK was 596,000 and long-term emigration was 323,000; net migration was therefore 273,000

long-term immigration for study was 126,000 (87,000 were non-EU nationals)

long-term emigration for former students was 62,000 (41,000 were non-EU nationals)

If all international students emigrated from the UK after their studies and immigration for study was remaining at similar levels, then we’d expect the immigration and emigration figures to be similar. Therefore, there’s a demand for more detailed information to explain the difference between these two flows.

Notes for: About this article

(i) Population Briefing: International Student Migration – What do the statistics tell us? (January, 2016) (ii) An update on international student migration statistics (November 2016)

International migration data and analysis: improving the evidence (February 2017)

ONS International Passenger Survey figures on long-term international migration (based on the UN definition of someone changing their country of residence for one year or more).

2. Our research so far

Our work since November 2016 has looked at:

how the International Passenger Survey (IPS) identifies departing international students

what Home Office visa statistics are available to explain the difference

producing a conceptual diagram to describe more fully what non-EU students may do at the end of their studies

There is, however, no single data source that records all possible outcomes for international students after they’ve completed their studies, which can answer the question “what do students do after their studies if so few are emigrating?” However, for non-EU national students (around 70% of total student immigration), data are published in the Home Office Immigration Statistics Quarterly Release on grants of extensions to stay by visa category and nationality. Additional analysis is available from the Home Office publication “Statistics on changes in migrants’ visa and leave status: 2015” (formerly known as “The Migrant Journey”), which shows how non-EU nationals changed their immigration status, and the immigration routes used prior to achieving settlement in the UK.

Home Office data1 also provide information on the numbers of non-EU nationals previously on a study visa who switched their visa type for work, family or other (non-study). Therefore, it’s possible that some of these former students also appear in the IPS departure figures.

Does this help explain the “gap” between the immigration and emigration figures for students? It will help explain some of the gap. However, it can’t fully explain the gap because the number of students completing their courses in any particular year won’t match the numbers immigrating unless immigration levels are steady and all courses are the same duration, which isn’t the case. Therefore, if precise figures were available on all outcomes of those students who have finished their studies, there’s likely to still be a gap (and in some years the immigration figures could be theoretically lower).

Notes for: Our research so far

- Table expc_01 Immigration Statistics Quarterly Release, October to December 2016. Home Office

3. Student outcomes and further work

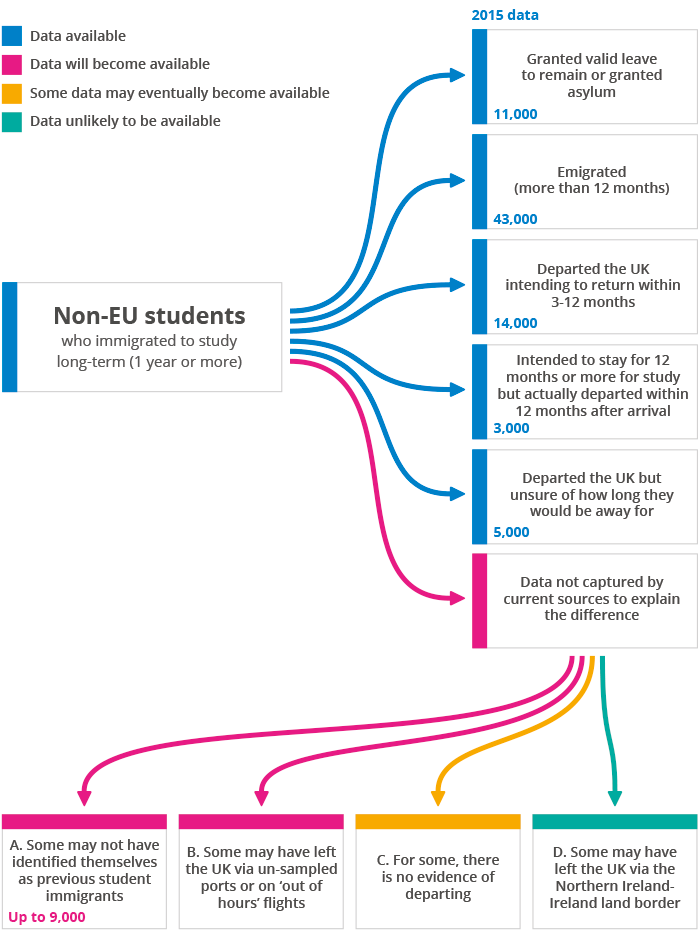

Figure 1 shows the different outcomes for non-EU international student immigrants after they’ve completed their studies. It shows where data sources are available; where they’ll become available; and the outcomes for students that may not be possible to measure with existing or planned data sources. It is provided for illustrative purposes only, since the inter-relationships between these sources are often complex and some students may appear on more than one overlapping source.

There are some outcomes that are likely to be explained as new data sources become available (for example, Home Office “exit checks” data); and some outcomes that may not be possible to measure with existing or even new data sources (for example, where international students may have left via the Common Travel Area or where there is no evidence of departing).

During 2017, we will continue working closely with other government departments to assess and develop new analyses based on administrative data sources. This includes:

collaborative analysis with the Home Office of its visas, Migrant Journey and "exit checks" data (introduced by the Home Office in April 2015); these data are likely to provide evidence relating to departures of some non-EU nationals who previously had study visas

linkage of HM Revenue and Customs’ PAYE data with Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) course completions data; these data will provide evidence of students remaining in the UK to work after completion of their studies, which will be particularly useful for EU nationals who are not included in Home Office visa data

linking HESA data on course completions in one year with new course enrolments in other years; for consecutive years, this will provide evidence of international students continuing to study in the UK following their initial courses (e.g. completing an undergraduate course and then enrolling on a postgraduate course)

analysis of cohorts of students, including evidence of their departure from the UK

In addition, in collaboration with the Centre for Population Change and Universities UK, we’ve launched an online international student survey to provide further information on international students’ post-study intentions; how sure they are of these intentions; their travel patterns whilst studying; use of public services; and working patterns whilst studying.

We will continue to identify how sharing, linking and exploiting other sources of data can help produce more detailed analysis of the impact of international migration on the economy and public services.

We plan to publish a further update in August 2017 to include the provisional results of this experimental work.

Figure 1: Outcomes of non-EU international student migrants who arrived for study in the UK for 12 months or more

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

There are a number of reasons why former students may not identify themselves as previous student immigrants. For example, students who extend their study visas or switch to other visa types would still be expected to leave the UK eventually (or acquire settlement). However, when they eventually leave they may not state that they originally immigrated to study in the UK. Some former students who acquire settlement may become British citizens and therefore respond to the International Passenger Survey (IPS) as a UK national. An improved understanding of those who were originally on study visas could come from “exit check” data (for those leaving after April 2015). These data link departure information with the Home Office visa system. Additionally, a departing person won’t be identified as a former student immigrant if they state that they’ve not been living in the UK for 12 months or more (which may happen if they’ve had short trips away from the UK). The online student survey will provide more information about this, with results expected mid-2017.

The IPS sample design is regularly reviewed to ensure that coverage and interviewing hours (6am to 10pm) are sufficient to ensure that all types of passengers are included. Since the data collected in the IPS is weighted to total passenger numbers, interviewing within these hours isn’t a problem unless passengers travelling outside these hours have different characteristics. During 2017, a pilot exercise will show if students are more likely to be missed (particularly during July to September when most student journeys take place). Results will be available early 2018.

If a visa has expired and the person has applied for a new visa, they may live in the UK while this process occurs. Further analysis of Home Office visa systems could give some indication of how many people, on average, have extended or applied for a new visit route whilst in the UK, after their last visa expired. There will never be a precise measure of how many people living in the UK have overstayed the duration of their visa. However, “exit check” data will provide information on how many departures were made by students whose visas had expired. Additionally, linking Higher Education Statistics Agency data with the HM Revenue and Customs' PAYE system will provide information on those who have completed Higher Education courses and then remained to work in the UK. (This will also be helpful for EU students). We expect to link these sources together and have initial results in 2017.

There are no suitable data available on land-border crossings between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, therefore it’s not possible to know how many international students have crossed this border and then departed from the Republic of Ireland. The number is expected to be small. Not all these categories are exclusive and it’s possible that some categories overlap.