Cynnwys

- Main points

- Introduction

- Trends in property crime

- Trends in police recorded property crime

- Existing theories on why property crime has fallen

- Metal theft

- Shoplifting

- Vehicle-related theft offences

- Theft from the person

- Fraud and cyber-crime

- Levels of victimisation

- Characteristics associated with being a victim of property crime

- Mobile phone ownership and theft

- Nature of CSEW property crime

- Property crime against businesses

- Background notes

1. Main points

Property crime covers a range of criminal activities where the aim is to either steal property or to cause damage to it. It is an important driver of overall crime, accounting for 70% of all police recorded crime in 2014/15 and 81% of all incidents measured by the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) in the same period.

Marked reductions have been seen in property crime since peak levels in the 1990s, with falls seen across both main measures of crime. The CSEW indicates that while there have been long-term declines across most types of property crime, the falls have been pronounced in vehicle-related theft, domestic burglary and criminal damage.

Cash and wallets or purses continue to be stolen in a high proportion of theft offences. However, as more people carry valuable electronic gadgets, these too have become desirable targets. For example, the latest data from the CSEW indicate that about half of theft from the person incidents involved the theft of a mobile phone.

The proportion of individual mobile phone owners experiencing theft in the year ending March 2015 was 1.2%, equivalent to 538,000 people. This is compared with 1.7% in the previous years CSEW, a reduction of 246,000 victims. This reduction may, in part, be explained by improvements to mobile phone security and theft prevention.

The value of items is an important factor in driving trends in theft. Metal theft provides a good example of this, with increases seen between 2009/10 and 2011/12, which corresponded with a spike in metal commodity prices. However, the most recent metal theft data from the police show that levels have continued to fall, with the 27,512 offences recorded during 2014/15 representing a decrease of 35% compared with 2013/14. These falls are also likely to reflect legislation introduced to tackle metal theft.

The 2014/15 CSEW showed that 4.6% of plastic card owners were victims of card fraud in the previous year, a much higher rate of victimisation than traditional offences such as theft from the person (0.9%). Estimates of the prevalence of plastic fraud have shown declines since peak levels in seen in 2009/10 (6.4%).

Consistent with previous years younger age groups were generally more likely to be victims than older age groups for most property crime types, according to the 2014/15 CSEW. Exceptions to this pattern were plastic card fraud and criminal damage where victimisation tended to be higher in the middle of the age distribution.

Those living in urban areas were more likely to be victims than those living in rural areas for most property crime types.

Respondents living in the most deprived output areas were most likely to be victims of household property crime offences such as burglary, vehicle-related theft and bicycle theft. Victims of plastic card fraud showed a contrasting pattern, where respondents living in the most deprived output areas (4.0%) were less likely to be victims than those living in the least deprived output areas (5.5%).

The characteristics of plastic card fraud victims were different from other types of property crime in many respects. In particular, the likelihood of victimisation did not vary significantly by age, those living in rural areas had a similar likelihood of victimisation compared with those living in urban areas (4.7% and 4.6% respectively), and victimisation was greater in higher-income households (6.4%) compared with those with a lowest incomes (3.4%).

2. Introduction

This bulletin provides an overview of statistics on property crime measured by the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) and recorded by the police1. The main trends and the more detailed CSEW data contained within the ‘Nature of Crime’ tables, published alongside this release are discussed. We also present some statistics on property crimes against businesses based on the Commercial Victimisation Survey (CVS)2. There is further information on each of these sources, in the ‘Data Sources and References’ section of this release.

Property crime is defined as incidents where individuals, households or corporate bodies are deprived of their property by illegal means or where their property is damaged. It includes offences of burglary and other household theft, vehicle offences (which include theft of vehicles or property from vehicles), bicycle theft, other personal theft, shoplifting, fraud, and criminal damage. For the purposes of this report, robbery3 is included as a property crime.

An assessment of our crime statistics by the UK Statistics Authority, found the statistics based on police recorded crime data did not meet the required standard for designation as National Statistics. Data from the CSEW continue as National Statistics. Further information on the interpretation of police recorded crime data is available in the ‘Data sources’ section.

Property crime accounted for 70% (2,902,371 offences) of all police recorded crime in 2014/15 and 81% (an estimated 5,465,000 incidents) of all crime covered by the 2014/15 CSEW. Of the crimes covered by the CVS, 86% in 2014 were property related (an estimated 4,103,000 offences). The consistently high proportion of offences accounted for by property crime means that these types of crimes, in particular the high volume ones such as vehicle-related theft, criminal damage and burglary, are important in driving overall crime trends.

The largest component of property crime in the 2014/15 CSEW was criminal damage (24%). Figure 1.1 shows a full breakdown. Comparing the composition of property crime in 1995 with the 2014/15 survey, the most noticeable difference is in vehicle-related theft, which has dropped from an estimated 4.3 million offences in 1995 (making up 28% of property crime) to an estimated 0.9 million offences in the 2014/15 survey (making up 17% of property crime). Improvements to vehicle security in recent years are likely to have contributed to the reduction seen in vehicle offences. Evidence from the Home Office Research Report, published in July 2014 on the drug epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s published in July 2014 suggests the rise and fall in vehicle related theft could also be partly attributed to the changing levels of illegal drug use. Domestic burglary also dropped substantially between 1995 (an estimated 2.4 million offences) and the 2014/15 survey (an estimated 0.8 million offences).

Looking at crimes experienced by children aged 10 to 154 based on the CSEW in the year ending March 2015, there were an estimated 278,000 incidents of personal theft and 59,000 incidents of criminal damage to personal property experienced by children aged 10 to 15. Around 62% of the thefts were classified as ‘Other theft of personal property’ (172,000 incidents), which includes thefts of unattended property.

Figure 1.1: Composition of Crime Survey for England and Wales property crime, year ending December 1995 and year ending March 2015

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1.1: Composition of Crime Survey for England and Wales property crime, year ending December 1995 and year ending March 2015

Image .csv .xlsLooking at the profile of property offences recorded by the police, in 2014/15 criminal damage and arson (17%) and ‘other’ theft offences (17%) were the two largest components. Theft from the person (3%), bicycle theft (3%) and robbery (2%) collectively accounted for a small proportion of all police recorded property crime. Figure 1.2 has a full breakdown.

In most respects, the profile of property crime recorded by the police has remained fairly stable. However, comparing the composition of police recorded property crime in 2014/15 with 2002/03, the most noticeable differences are:

- fraud made up 20% of property crime (593,150 offences) in 2014/15 compared with 4% (183,683 offences) in 2002/03

However, it should be noted that increases in fraud offences can at least in part be attributed to the extended coverage of police recorded fraud. As a result of recent improvements to the coverage of official statistics, 2014/15 data on fraud recorded by the police include offences reported to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB) via industry bodies Cifas and Financial Fraud Action UK). As such, it is not possible to make direct comparisons with police recorded fraud figures from 2002/03. Further information is available in the sections on trends in police recorded crime and fraud and cyber crime.

vehicle offences made up 12% in 2014/15 compared with 22% of property crime in 2002/03

shoplifting6 accounted for 11% of property crime in 2014/15 compared to 6% in 2002/03, although the number of shoplifting offences recorded by the police remained roughly the same (326,440 in 2014/15 compared with 310,881 in 2002/03)

Figure 1.2: Composition of police recorded property crime in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 and year ending March 2015

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

- Fraud offences were recorded by Action Fraud and National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (through Cifas and Financial Fraud Action UK) from the year ending March 2012 to the year ending March 2015. Comparisons between earlier years are not directly comparable due to fraud offences coming from new data collections and the implementation of improved recording practices since the year ending March 2012

Download this chart Figure 1.2: Composition of police recorded property crime in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 and year ending March 2015

Image .csv .xlsOwing to a change in recording practices brought about by the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard7 (NCRS) April 2002, it is not possible to make direct long-term comparisons of police recorded crime prior to 2002/03.

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 are not directly comparable because the population, offence coverage and volume of offences differ between the CSEW and police recorded crime.

Notes for introduction

Police recorded crime data presented in this chapter are those notified to the Home Office and were recorded in the Home Office database on 3 September 2015.

Data from the CVS are classified as Official Statistics as they have not yet been assessed for National Statistics status.

Robbery is an offence in which violence or the threat of violence is used during a theft (or attempted theft) and, within the quarterly statistical release, is reported as a separate, standalone category in both the police recorded crime and CSEW data series. As robbery involves an element of theft, it is included within this ‘Focus on: Property crime’ publication.

Based on the preferred measure of crime. More information about the preferred and broad measures of crime against children aged 10 to 15 can be found in Section 2.5 of the User Guide to Crime Statistics for England and Wales (1.36 Mb Pdf).

Based on the preferred measure of crime. More information about the preferred and broad measures of crime against children aged 10 to 15 can be found in Section 2.5 of the User Guide to Crime Statistics for England and Wales (1.36 Mb Pdf).

Shoplifting offences are not covered by the CSEW which is a survey of the household population.

The NCRS, introduced in April 2002, was designed to ensure greater consistency between forces in recording crime and to take a more victim-oriented approach to crime recording, with the police being required to record any allegation of crime unless there was credible evidence to the contrary.

3. Trends in property crime

CSEW property crime

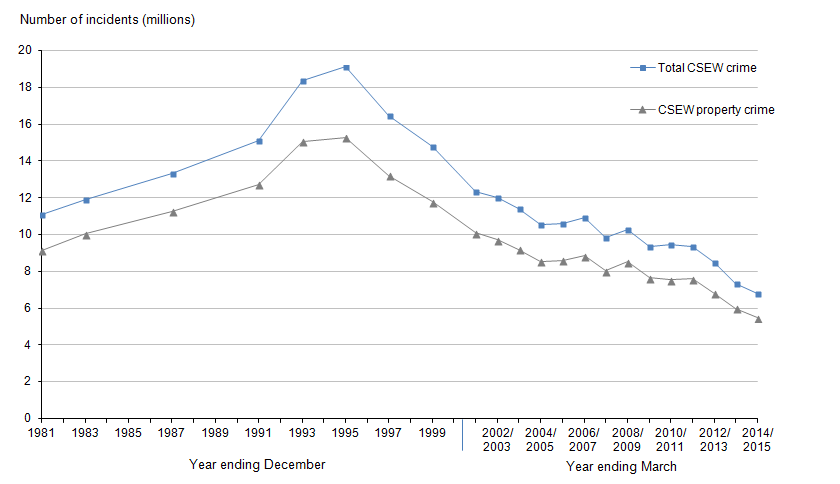

The proportion of all Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) crime accounted for by property crime has remained relatively stable over time; it has comprised at least 80% since the survey began, indicating the importance of property crime in driving overall CSEW trends. Steady increases were seen from 1981 when the survey started, peaking in 1995. Since then levels of property crime have declined and estimates from the 2014/15 CSEW were 64% lower than 1995 (Figure 1.3). This trend is consistent with that seen in many other countries (Exploring the international decline in crime rates, Tseloni et al., 2010).

Figure 1.3: Long-term trends in total Crime Survey for England and Wales crime and property crime, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Prior to the year ending March 2002, CSEW respondents were asked about their experience of crime in the previous calendar year, so year-labels identify the year in which the crime took place. Following the change to continuous interviewing, respondents' experience of crime relates to the full 12 months prior to interview (that is, a moving reference period), so year-labels from the year ending March 2002 onwards identify the CSEW year of interview

Download this image Figure 1.3: Long-term trends in total Crime Survey for England and Wales crime and property crime, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

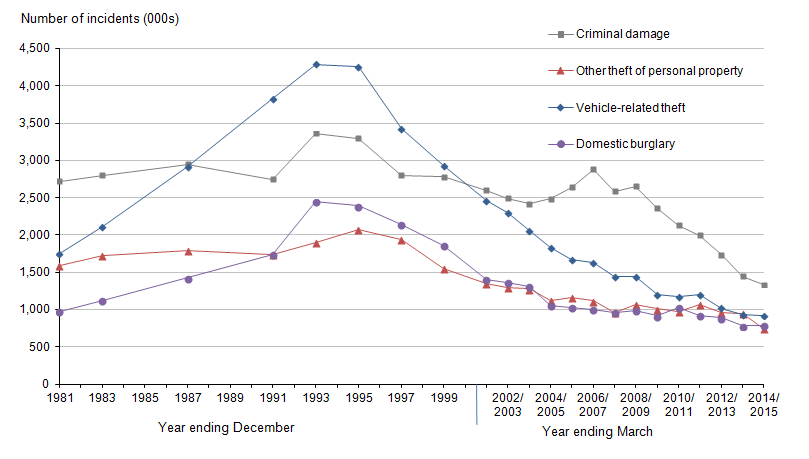

.png (23.8 kB) .xls (33.8 kB)Figure 1.4 shows the trend for a number of the high volume property crime types. Most of these show a similar trend to overall CSEW property crime with levels peaking in either 1993 or 1995, followed by a general decline. Criminal damage has followed a slightly different pattern, peaking in the 1993 survey with 3.4 million incidents followed by a series of modest falls (when compared with other CSEW offence types) until the 2003/04 survey (2.4 million offences). There was then a short upward trend until the 2006/07 CSEW (2.9 million offences), after which there were falls to its current level, the lowest since the survey began.

Figure 1.4: Long-term trends in Crime Survey for England and Wales criminal damage, other theft of personal property, vehicle-related theft and domestic burglary, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Prior to the year ending March 2002, CSEW respondents were asked about their experience of crime in the previous calendar year, so year-labels identify the year in which the crime took place. Following the change to continuous interviewing, respondents' experience of crime relates to the full 12 months prior to interview (that is, a moving reference period), so year-labels from the year ending March 2002 onwards identify the CSEW year of interview

Download this image Figure 1.4: Long-term trends in Crime Survey for England and Wales criminal damage, other theft of personal property, vehicle-related theft and domestic burglary, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

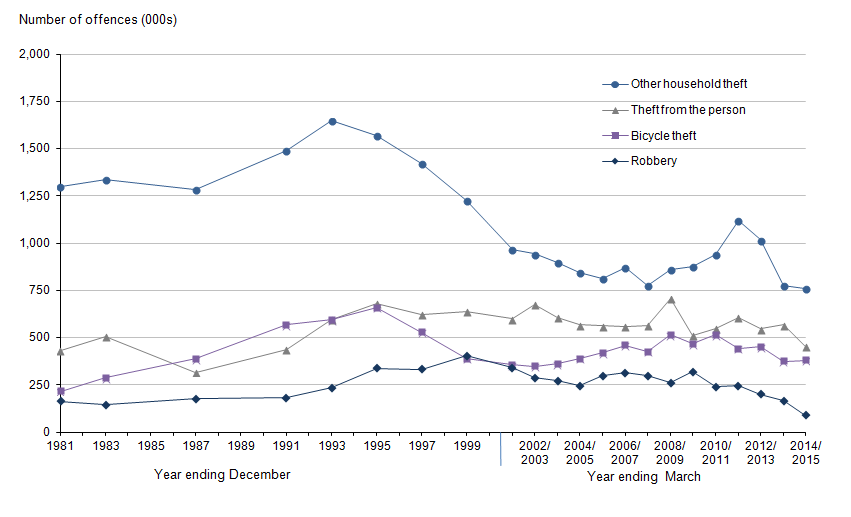

.png (32.3 kB) .xls (32.3 kB)Figure 1.5 shows the long term trends in CSEW ‘other household theft’1, theft from the person2, bicycle theft and robbery from 1981 to 2014/15. These crime types have shown somewhat different trends compared with those seen for overall CSEW property crime (Figure 1.3):

‘Other household theft’ peaked in 1993 and then declined until around the mid-2000s. This was then followed by an upward trend between the 2007/08 and 2011/12 surveys. Since 2011/12 there has been a general decline in ‘other’ household theft where the 2014/15 estimate (760,000 offences) has decreased to a level similar to that seen in 2007/08 (778,000 offences)

the trend in theft from the person has remained relatively flat since the mid-1990s. Estimates of the volume of theft from the person offences have shown a slight downward trend over the period from the late 1990s. In the 2014/15 survey a fall of around 21% was seen compared to the previous year. This is consistent with the change seen in police recorded crime for this offence type and similar to decreases seen in other theft categories such as other theft of personal property

bicycle theft peaked in 1995 and then declined until around the early-2000s. Since 2002/03 while the overall trend has remained relatively flat there has been some fluctuation year on year

robbery has remained a low volume offence across the history of the survey, typically accounting for around 2 to 3% of CSEW property crime. Levels have fluctuated from year to year and showed a small upward trend during the 1990s, peaking in the 1999 survey, before falling to levels similar to those seen in the 1980s. However, it should be noted that owing to the small number of robbery victims interviewed, CSEW estimates have large confidence intervals and are prone to fluctuation

there is no clear trend within the estimates for property crime experienced by children aged 10 to 15 as data are only available from 2009/10 onwards. The relatively small number of children aged 10 to 15 interviewed by the CSEW means that the estimates for crime experienced by children aged 10 to 15 are much more prone to year-on-year fluctuation than estimates from the CSEW for adults aged 16 and over

Figure 1.5: Long-term trends in Crime Survey for England and Wales other household theft, theft from the person, bicycle theft and robbery, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Prior to the year ending March 2002, CSEW respondents were asked about their experience of crime in the previous calendar year, so year-labels identify the year in which the crime took place. Following the change to continuous interviewing, respondents' experience of crime relates to the full 12 months prior to interview (i.e. a moving reference period), so year-labels from the year ending March 2002 onwards identify the CSEW year of interview

Download this image Figure 1.5: Long-term trends in Crime Survey for England and Wales other household theft, theft from the person, bicycle theft and robbery, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

.png (31.6 kB) .xls (32.8 kB)Notes for trends in property crime

Thefts from inside a dwelling by someone who had the right to be there (in contrast to domestic burglary, where the offender did not have the right to be there) and thefts from outside a dwelling.

Thefts of property being held or carried by someone, but no or minimal force is used (in contrast to robbery, where non-minimal force, or the threat of, is used).

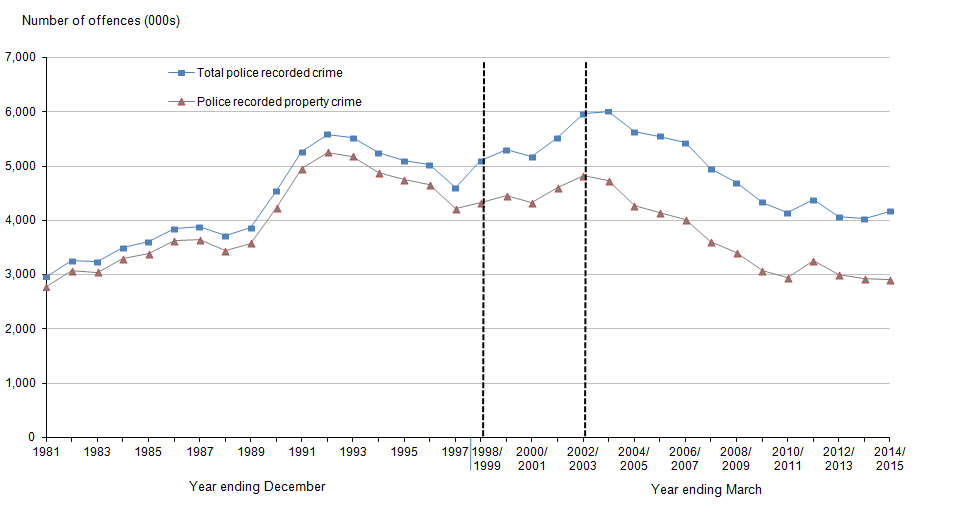

4. Trends in police recorded property crime

Following changes to the Home Office Counting Rules (HOCR) in 1998 and the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in 2002, police recorded crime data from 2002/03 onwards are not directly comparable with earlier years1. However, overall long-term trends in property crime are not likely to have been substantially affected by the above changes. The trend in police recorded property crime has been similar to that seen for the CSEW, rising during the 1980s before peaking in the 1990s and showing gradual decreases for the majority of the 2000s and beyond (Figures 1.3 and 1.6).

After concerns were raised about the quality of crime recording by the police in late 2013 Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) carried out a national inspection of crime data integrity during 2014. In their final report ‘Crime-recording: making the victim count’ HMIC concluded that, across England and Wales as a whole, an estimated 1 in 5 offences (19%) that should have been recorded as crimes were not. The greatest levels of under-recording were seen for violence against the person offences (33%) and sexual offences (26%). However there was considerable variation in the level of under-recording for different offence types investigated and levels of compliance with recording standards were judged to have been better for property crime types (for example, 11% under-recording of burglary, and 14% for robbery and criminal damage). Following the publication of the HMIC report action taken by police forces to improve their compliance with the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) is likely to have resulted in the increase in the number of offences recorded. This has contributed to the increase in overall police recorded crime, which saw a 4% rise between 2013/14 and 2014/15. However, the effect of recording improvements has been seen mainly for violent crimes and sexual offences, and is likely to be substantially less pronounced in property crime offences.

As with crime measured by the CSEW, the trend in police recorded property crime is similar to the trend for all police recorded crime. Property crime has shown year-on-year falls and was 40% lower in volume in 2014/15 (2,902,371 offences) than in 2002/03 (4,821,745 offences). This represents a faster rate of reduction than overall police recorded crime which fell by 36% over the same period. Thus, the proportion of total police recorded crime accounted for by property crime2 has decreased by 11 percentage points; from 81% in 2002/03 to 70% in 2014/15. Reflecting this change, the relative contribution of other crime types have increased slightly over this period; the biggest being violence against the person, with an increase of 7 percentage points (from 12% in 2002/03 to 19% in 2014/15). Full data tables are available in Crime in England and Wales for year ending March 20153.

Figure 1.6: Trends in total police recorded crime and police recorded property crime in England and Wales, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

- Following changes to the Home Office Counting Rules (HOCR) in 1998 and the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in 2002, data from the year ending March 2003 onwards are not directly comparable with earlier years; nor are data between the year ending March 1999 and year ending March 2002 directly comparable with data prior to the year ending March 1999

- Fraud offences include incidents recorded by Action Fraud and National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (through Cifas and Financial Fraud Action UK) from the year ending March 2012 to the year ending March 2015

Download this image Figure 1.6: Trends in total police recorded crime and police recorded property crime in England and Wales, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

.png (29.6 kB) .xls (32.8 kB)With regard to specific property crime types covered in this overview, discussions of trends have been restricted to the period 2002/03 to 2014/15, where data are more comparable.

Similar to the CSEW police recorded vehicle offences and burglary have shown the largest decreases in volume over the last decade. Between the years 2002/03 and 2014/15; vehicle offences were down by 67% (to 351,458 offences) and burglary down by 54% (to 411,425 offences) as seen in Figure 1.7. These decreases have been the main drivers on the overall downward trend in property crime.

‘(All) other theft offences’ showed a 4% decrease in 2014/15 compared with the previous year. The trend has been generally downward, other than a short period of increases between 20010/11 and 2011/12 (Figure 1.7). ‘Other theft offences’ the largest subcategory of ‘(all) other theft offences’ includes theft of both personal property such as wallets or phones and property from outside peoples’ homes, such as garden furniture, as well as metal theft from businesses.

This ‘other theft offences’ subcategory comprises mostly of the theft of unattended items and accounted for 73% (360,021 offences) of the overall ‘all other theft offences’ (493,617 offences) in 2014/15. The police recorded ‘other theft offences’ category includes crimes against businesses and other organisations not covered by the CSEW but it is not possible to separately identify thefts against such victims in centrally held police recorded crime data (this type of crime is covered by the Commercial Victimisation Survey for some business sectors).

‘Other theft offences’ have seen a 7% decrease in 2014/15 compared with the previous year, consistent with declining trends seen over the last 3 years. A short period of increase was seen between 2010/11 and 2011/12. This rise was thought to have been driven by a surge in metal theft over this period which corresponds with a spike in world commodity prices. Recent evidence suggests that such offences are now decreasing and should be seen in the context of metal theft legislation which came into force in May 2013 (further information is given in the metal theft section).

Fraud offences have increased by 14% (to 593,150 offences) in 2014/15 compared with 2013/14, a rise consistent with previous years since 2011/12. Although over recent years fraud offences appear to have been increasing while many other forms of property crime have fallen, trends in fraud over this period are difficult to interpret for a number of reasons:

new arrangements for the reporting and recording of fraud offences via Action Fraud, (a public facing national reporting centre that records incidents reported directly by the public and by organisations) is likely to have had an impact on the reporting and recording of such offences

the centralisation of fraud recording may have led to improved recording practices and a greater proportion of reported incidents being recorded as crimes

the police recorded crime series recent extension to the coverage of the statistics include data from 2 industry bodies, the police recorded crime figures we publish now include referrals to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (within the City of London Police) from Cifas and Financial Fraud Action UK (FFA UK)

A limited time series for these new sources is available back to 2011/12. When looking at trends it is important to note that statistics on fraud offences recorded by the police in earlier years are not comparable as they are limited to those offences recorded by individual police forces.

Figure 1.7: Trends in selected police recorded theft offences in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1.7: Trends in selected police recorded theft offences in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015

Image .csv .xlsNotes for trends in police recorded property crime

Changes to the HOCR and the introduction of the NCRS had a greater impact on the number of violent crimes recorded by the police; see Section 5.1 of the User Guide to Crime Statistics for England and Wales (1.36 Mb Pdf) for more information.

Including robbery.

The police recorded crime series will have been subject to revisions since the Crime in England and Wales year ending March 2015 publication was released (the changes will be small and will not affect the percentages above).

5. Existing theories on why property crime has fallen

The reduction in property crime has been an important factor in driving falls in overall crime and various theories have been put forward to explain these falls. Many of them are contested and subject to continuing discussion and debate1, some of these include:

the rise in the use of the internet has roughly coincided with falls in crime (in 1995 use of the internet was not widespread). As it became more popular, it may have helped to occupy young people’s time when they may otherwise have turned to crime. Farrell et al., 2011 suggests the internet also provides more opportunity for online crime

reduced consumption of drugs and alcohol is likely to have resulted in a drop in offending (Bunge et al., 2005). A 2014 Home Office research paper ‘The heroin epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s and its effect on crime trends - then and now’ supports the notion that the changing levels of opiate and crack-cocaine use have affected acquisitive crime trends in England and Wales, potentially explaining over half of the rise in crime in the 1980s to mid-1990s and between a quarter and a third of the fall in crime since the mid-1990s

significant improvements in forensic and other crime scene investigation techniques and record keeping, such as fingerprinting and DNA testing may have led to a reduction in crime. Given the prominence of these advancements, perceived risk to offenders may have increased, inducing a deterrent effect (Explaining and sustaining the crime drop: Clarifying the role of opportunity-related theories, Farrell et al., 2010)

an American study has suggested that the introduction of legalised abortion on a wide number of grounds meant that more children who might have been born into families in poverty or troubled environments and be more prone to get drawn into criminality, would not be born and therefore be unable to commit these crimes (The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime, Donohue and Levitt, 2001). However, this theory has been contested by others (for example, The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime: Comment, Foote and Goetz, 2005)

changes (real or perceived) in technology and infrastructure, including security technology such as CCTV, may act as deterrents to committing crime (CCTV has modest impact on crime, Welsh and Farrington, 2008)

the impacts of longer prison sentences and police activity on reducing crime, particularly property crimes, are likely to act as deterrents (Acquisitive Crime: Imprisonment, Detection and Social Factors, Bandyopadhyay et al., 2012).

Increased quality of building and vehicle security is also likely to have been a factor in the reduction in property crime. This concept of ‘target-hardening’ which makes targets (that is, anything that an offender would want to steal or damage) more resistant to attack is likely to deter offenders from committing crime (Opportunities, Precipitators and Criminal Decisions: A reply to Wortley's critique of situational crime prevention, Cornish and Clarke, 2003).Findings from the CSEW add some evidence which may support this, indicating that alongside the falls in property crime, there were also improvements in household and vehicle security.

Since 19952, there have been statistically significant increases in the proportion of households in the 2014/15 CSEW ( ‘Nature of Crime’ table 3.12 (370.5 Kb Excel sheet) ) with:

window locks (up 21 percentage points from 68% to 89% of households)

light timers/sensors (up 16 percentage points from 39% to 55% of households)

double/dead locks (up 12 percentage points from 70% to 82% of households)

burglar alarms (up 11 percentage points from 20% to 31% of households)

There have also been statistically significant reductions in vehicle-related theft resulting from offenders gaining entry by forcing locks (39% of vehicle-related theft incidents in the 1995 CSEW; compared to 17% in the 2014/15 survey) or breaking windows (40% of vehicle-related theft incidents in the 1995 CSEW; compared to19% in the 2014/15 survey).

Notes for existing theories on why property crime has fallen

ONS does not endorse any one of the theories over the others.

Sourced from ‘Nature of burglary, 2007/08’ tables (the latest published data on home security measures from the 1996 CSEW).

6. Metal theft

Metal thefts refer to the theft of items for the value of their constituent metals, rather than the attainment of the item itself. There is no specific separate criminal offence of metal theft and so it is not possible to identify such crimes within the main recorded crime collection. However, a separate data collection from police forces has been established by the Home Office to identify the extent of metal theft. Forces can flag theft offences that involve metal theft and break these offences down further as relating to either infrastructure or non-infrastructure. Infrastructure related thefts involve the removal of metal that has a direct impact on the functioning or structure of buildings or services. This includes the theft of metal from live services. For example, the theft of railway cabling which causes major disruption to passenger travel, the theft of lead roofing from churches and historical buildings and power suppliers are targeted for their copper cabling which can impact on communities when it results in power loss. Non-infrastructure related metal thefts involve the removal of metal that has no direct impact on the functioning or infrastructure of buildings or services. This includes theft of redundant metals, abandoned vehicles, and gates/fencing.

Metal theft offences affect a range of sectors, notably telecommunications, transport and power suppliers. Other affected sectors include water suppliers, construction and local authorities, as well as individuals and businesses. While metal theft offences were at peak levels, the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) estimated that metal theft offences cost the UK economy around £770 million every year (Tackling metal theft - A councillor’s handbook, Local Government Association, 2013). Metal theft offences have cost the bill payer in terms of repair, security and prevention measures, and labour.

Table 1.1 shows there were 27,512 metal theft offences recorded by the 44 police forces in England and Wales including British Transport Police in 2014/15, a decrease of around a third (35%) compared with the previous year. Table 1.1 also provides a breakdown by infrastructure and non-infrastructure related offences. In 2014/15, 42% of metal theft offences were infrastructure related whilst 58% were non-infrastructure related. In 2012/13 infrastructure related theft accounted for 51% of offences, in 2013/14 it accounted for 46%. This suggests that although the fall in metal theft offences is driven by a reduction in both infrastructure and non-infrastructure related metal thefts, infrastructure is the biggest driver in overall falls.

Table 1.1: Metal theft offences recorded by the police in England and Wales, year ending March 2013 to year ending March 2015 [1,2]

| England and Wales | ||||

| Number of offences | Apr '14 to Mar '15 compared with previous year (% change) | |||

| Apr '12 to Mar '13 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | Apr '14 to Mar '15 | ||

| Infrastructure related2 | 27,153 | 16,549 | 9,860 | -40 |

| Non-infrastructure related2 | 25,599 | 19,165 | 13,600 | -29 |

| All metal theft3 | 62,348 | 42,156 | 27,512 | -35 |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics. | ||||

| 2. Breakdowns given for infrastructure and non-infrastructure related offences will not sum to total metal theft offences. Includes data from 37 police forces in England and Wales (excluding Cleveland, Norfolk and Leicestershire who did not provide a complete infrastructure/non-infrastructure breakdown in the year ending March 2013, Devon and Cornwall who did not provide a full breakdown for years ending March 2013 to March 2015, North Wales and West Midlands who recorded all offences in year ending March 2013 as infrastructure only and Wiltshire who recorded some offences in year ending March 2013 as both infrastructure and non-infrastructure). | ||||

| 3. Excludes Norfolk for year ending March 2013 as they did not provide a full year's worth of data. All 44 forces are included in subsequent years. | ||||

Download this table Table 1.1: Metal theft offences recorded by the police in England and Wales, year ending March 2013 to year ending March 2015 [1,2]

.xls (28.7 kB)The overall decline in metal theft offences recorded by the police has occurred alongside government initiatives to tackle the prevalence of metal theft incidences. The government provided £5million in funding in November 2011 to implement the National Metal Theft Taskforce. The taskforce received continued funding until September 2014 when government funding ended. Funding ended because it was believed there has been sufficient time for legislative reforms to have become well established, for co-ordinated enforcement to have taken place, and for police forces to have developed and implemented proposals to embed tackling metal theft within their normal business.

Operation Tornado, a joint initiative between British Transport Police, Home Office, police forces and the scrap metal industry, was implemented in January 2012. The scheme required participating scrap metal dealers to take voluntary additional steps to check the identity of individuals selling scrap metal and a more focused, co-ordinated law enforcement response. This was aimed not to inhibit individuals that operate legitimate businesses rather to identity dealers who operate outside the law.

Other changes have been implemented as part of the Scrap Metal Dealer’s Act 2013. This included the banning of cash payments for scrap metal, which was introduced in December 2012 and became mandatory for all scrap metal dealers in October 2013. Other requirements introduced by the Scrap Metal Dealer’s Act 2013 required all individuals and businesses to obtain a scrap metal dealer’s licence. Local authorities have the power to decline unsuitable applicants and revoke licences where necessary. It also requires all metal sellers to provide proof of identity at the point of sale and for dealers to keep intensive records of their suppliers, increasing traceability of metal transactions.

In 2015 the Home Office produced an evaluation of Government interventions aimed at reducing metal theft. Even when controlling for the price of metal and other factors driving acquisitive crime the analyis reported a large, statistically signifcant, effect on the levels of metal theft by the interverntions launched during Operation Tornado and the Scrap Metal Dealer’s Act.

Metal theft by offence type

The Home Office Data Hub (HODH) collects record level crime data supplied by police forces. Although ‘metal theft’ is not a specific offence code within police recorded crime if police believe an offence to by related to metal theft, they can flag it as such. It is possible to gain further detail on the nature of flagged metal theft offences using the HODH1, including the specific types of offences, infrastructure or non-infrastructure. The following analysis uses data from 19 forces that were deemed by Home Office analysts to provide good metal theft data to the HODH for 2014/15.

Figure 1.8 shows that in 2014/15 around 58% of metal theft offences recorded by the police were part of the offence classification ‘other theft offences’. This includes thefts not classified elsewhere, the removal of articles from public places such as unattended personal property and theft from organisations (such as electricity suppliers). This was followed by burglary and vehicle offences which accounted for 22% and 18% of all metal theft offences. Around 76% of burglary offences involving metal theft were recorded as non-domestic burglary with the remaining 24% of offences recorded as domestic burglary.

Figure 1.8: Metal theft offences recorded by the police in England and Wales, by offence type, Home Office Data Hub, year ending March 2015

Source: Home Office Data Hub, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

- Data based on 19 forces that provided accurate data via the Home Office Data Hub

- Percentages do not add up to 100 as a small proportion of metal theft offences (less than 1%) fall into categories which are not property crime related and are therefore not included in this figur

Download this chart Figure 1.8: Metal theft offences recorded by the police in England and Wales, by offence type, Home Office Data Hub, year ending March 2015

Image .csv .xlsNotes for metal theft

- The HODH collects record level crime data supplied by the forces which provides detailed information about the crimes committed.

7. Shoplifting

While recent trends show continuing falls in most types of property crime, there have been some small increases seen in specific crime types, including shoplifting. The longer term trend in shoplifting recorded by the police is different from that seen for other theft offences. While most theft offences saw steady declines over much of the last decade, incidents of recorded shoplifting have shown comparatively little change over this time (Figure 1.9).

Shoplifting accounted for 8% of all police recorded crime in the year ending March 2015. The police recorded 326,440 shoplifting offences in this period, a 2% increase compared with the previous year and the highest volume since the introduction of the NCRS in 2002/03. However, the latest increase represents a slowing of the rise compared with the previous year. Police recorded crime figures for year ending March 2015 showed that across England and Wales there were 5,375 more shoplifting offences when compared with the previous year. There were reported increases in 25 of the 44 police force areas in March 2015. Overall, while it is possible that there have been some genuine rises in the incidence of shoplifting the balance of evidence suggests that the increase in offences recorded by the police are likely to reflect a change in reporting practice leading to a greater proportion of shoplifting offences being reported to the police.

This is supported by the 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey which provides an alternative measure of shoplifting (referred to in the survey as ‘theft by customers’); it includes crimes not reported to the police as well as those that have been1. In 2014, the number of thefts by customers incidents decreased by 36% per 1,000 premises in the wholesale and retail sector compared with 2012. However, thefts by customers still accounted for the largest number of all crime types against this business sector, with 2.1million incidents in the 12 months prior to interview (6,695 incidents per 1,000 premises).

Additionally, increased reporting is consistent with findings from a separate British Reail Consortium (BRC) survey which showed that, while their members had experienced greater losses (as the average value of losses have risen), the number of incidents of shoplifting in 2013/14 has fallen compared with the previous year.

Figure 1.9: Trends in police recorded shoplifting offences in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1.9: Trends in police recorded shoplifting offences in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015

Image .csv .xlsNotes for shoplifting

- Results from the 2014 CVS survey relate to interviews carried out between August and November 2014, when interviewers asked about the incidents of crime experienced in the 12 months prior to interview. This is an earlier time period than the latest police recorded crime figures which cover crimes recorded in the year ending March 2015.

9. Theft from the person

Theft from the person involves offences where there is theft of property, while the property is being carried by, or on the person of, the victim. These include snatch thefts (where an element of force may be used to snatch the property away) and stealth thefts (where the victim is unaware of the offence being committed, for example, pick-pocketing). Unlike robbery, these offences do not involve violence or threats to the victim.

While most theft offences saw steady declines in the number of crimes recorded by the police over much of the last decade, levels of recorded theft from the person, although generally declining since 2002/03, saw a period of year-on-year increases between 2008/09 and 2012/13. Over this period there was an average annual increase of 5% in theft from the person offences recorded by the police. More recently in the last 2 years the downward trend has resumed, and the number of theft from the person offences recorded by the police fell by 20% between 2013/14 and 2014/15 (Figure 1.10).

It is thought that the increase seen in the police recorded crime data between 2008/09 and 2012/13 may be due to people carrying more valuable items than previously, such as more advanced smartphones and tablet computers which attract high value in the stolen goods market. Analysis conducted on London-specific data during the period August 2012 to January 2014 in a recent Home Office research paper ‘Reducing mobile phone theft and improving security’ indicates that certain smartphones are significantly more likely to be targeted.

The concept of ‘target-hardening’, in relation to buildings and vehicles, is also being applied by phone providers to mobile phones. The Home Office research suggests that the release of a more advanced operating system for mobile devices (iOS7) in September 2013, that introduced enhancements in security, is likely to have contributed to the substantial reduction in mobile phone thefts in London. If this effect was replicated across the whole of England and Wales, it may help to explain the 20% decrease in theft from the person offences recorded by the police in 2014/15 compared with the previous year, ther section on CSEW mobile phone ownership and theft has more information.

Figure 1.10: Trends in police recorded theft from the person offences in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1.10: Trends in police recorded theft from the person offences in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015

Image .csv .xls10. Fraud and cyber-crime

The extent of fraud is difficult to measure because it is a deceptive crime, often targeted indiscriminately at organisations as well as individuals. Some victims of fraud may be unaware they have been a victim of crime, or that any fraudulent activity has occurred. Others may be reluctant to report the offence to the authorities, feeling embarrassed that they have fallen victim. The level of fraud reported to the police is thought to significantly understate the true level of such crime.

Official statistics on fraud draw on a range of sources, including administrative data on fraud referred to the police and data from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW). No individual source provides a complete measure of the overall extent of fraud offences, but together they help to provide a fuller picture.

To help meet the increasing demand for better statistics, we have been working to improve the collection and presentation of official statistics on fraud by drawing in new sources and expanding current collections. This includes work to extend the CSEW to cover fraud and elements of cyber crime into the survey's main crime estimates. Improvements have also been made to the administrative data on fraud recorded by the police, which have now been extended to incorporate crime reported by industry bodies.

Concerning improvements to administrative sources, in addition to offences recorded by Action Fraud, the coverage of police recorded crime data on fraud has been extended to include offences of fraud reported to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB)1 by 2 industry bodies; Cifas and Financial Fraud Action UK (FFA UK). Statistics based on this increased coverage were first published in October 2015 in the quarterly bulletin for the year ending June 2015. As a result, police recorded fraud data presented in this bulletin differ from the year ending March 2015 bulletin and the Focus on Property Crime, 2012/13 which did not include figures from Cifas or FFA UK. Based on the newly extended coverage in the year ending March 2015, a total of 593,150 fraud offences were recorded by the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau in England and Wales, an increase of 14% compared with the previous year.

Regarding work to extend the CSEW, a large scale field trial to extend the main victimisation module to cover fraud and elements of cyber-crime was carried out between May and August 2015 (more information is available in the methodological note ‘Extending the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) to include fraud and cyber crime’ (382.4 Kb Pdf)). It should be noted that these statistics from the field trial have been published as research outputs and not official statistics. The new questions are designed to cover a broad spectrum of fraud and computer misuse crimes, including those committed in person, by mail, over the phone and online. They also encompass a range of harm or loss, including incidents where the victim suffered no or little loss or harm, or experienced significant harm or loss and cases where losses were reimbursed by others (such as bank or credit card company). Preliminary results from this field trial were published in the briefing note on ‘Improving crime statistics in England and Wales: Developments in the coverage of fraud’ and the results indicated that:

there were an estimated 5.1 million incidents of fraud, with 3.8 million adult victims in England and Wales in the 12 months prior to interview; just over half of these incidents involved some initial financial loss to the victim, and includes those who subsequently received compensation in part or full

where a loss was reported, three-quarters (78%) of the victims received some form of financial compensation, and in well over half (62%) they were reimbursed in full

in addition to fraud, the field trial estimated there were 2.5 million incidents of crime falling under the Computer Misuse Act, the most common incident where the victim’s computer or other internet enabled device was infected by a virus; it also included incidents where the respondent’s email or social media accounts had been hacked

It is important to recognise that these new data are not simply uncovering new crimes, but finding better ways of capturing existing crime that has not been measured well in the past. It is not possible to say whether these new figures represent an increase or decrease compared with earlier levels and it will be some years before year on year comparisons can be reliably made. It is therefore not valid to simply add these new estimates to the existing 2014/15 CSEW estimates and compare them with the previous year’s total.

There are a number of reasons why the number of offences reported to the police (via Action Fraud, Cifas or FFA UK) was so much lower than estimates from the CSEW field trial. The profile of cases covered by the CSEW cover the full spectrum of harm or loss. Reporting rates are likely to be lower in cases where there is low or no harm, but merely inconvenience, to the victim. In contrast, offences reported to the police are likely to represent the more serious end of the spectrum, where the scale of financial loss or emotional impact on the victim is greater and victims are more likely to report the offence.

As many of the statistics on fraud and cyber-crime are subject to ongoing development work it is difficult, at this stage, to provide a clear picture of trends over time. However, the CSEW does collect some statistics on the prevalence of plastic card fraud as part of a separate module of the survey. Figures for the year ending March 2015 CSEW showed that 4.6% of plastic card owners were victims of card fraud in the last year, a statistically significant decrease from the 5.1% estimated in the previous year. The overall trend shows a decline in levels of plastic card fraud following a rise between the 2005/06 and 2009/10 surveys. The statistical bulletin, Crime in England and Wales, year ending March 2015 contains further discussion of these trends.

Further information on the ongoing improvements to statistics on fraud and cyber crime, and how to interpret the existing evidence on trends is available in ‘Improving crime statistics in England and Wales: Developments in the coverage of fraud’.

Notes for fraud and cyber-crime

- A government funded initiative run by the City of London Police, who lead national policing on fraud.

11. Levels of victimisation

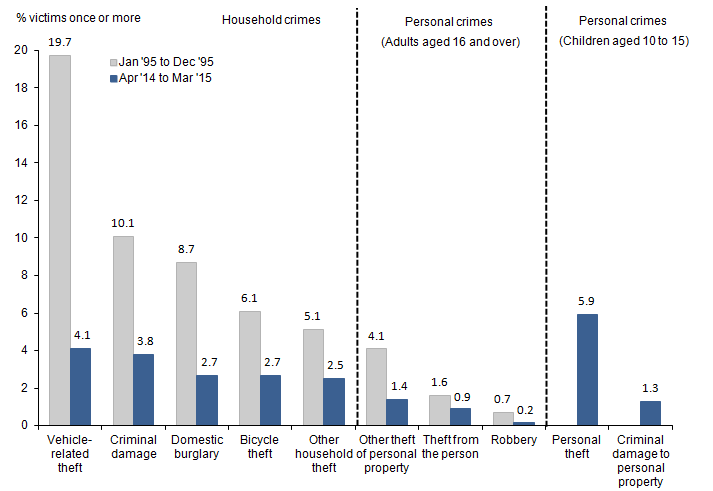

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) provides estimates of victimisation rates for the crimes that it covers, and these vary by property crime type (Figure 1.11). In the 2014/15 CSEW, 4.1% of vehicle-owning households had experienced vehicle-related theft and 3.8% of households had experienced criminal damage. In contrast, 0.9% of adults had been a victim of theft from the person and 0.2% had been a victim of robbery. 5.9% of children aged 10 to 15 had been a victim of personal theft1 and 1.3% had been a victim of criminal damage to personal property. In the separate victimisation module 4.6% of plastic card owners were victims of card fraud.

Comparing victimisation rates in 1995 (when crime was at its peak) with the 2014/15 CSEW:

the most noticeable difference is in vehicle-related theft which decreased from 19.7% of vehicle-owning households experiencing a vehicle-related theft in 1995 to 4.1% in the 2014/15 CSEW

criminal damage has shown a decrease from 10.1% of households experiencing criminal damage in 1995 to 3.8% in the 2014/15 CSEW

domestic burglary has also shown a decrease from 8.7% of households experiencing domestic burglary in 1995 to 2.7% in the 2014/15 CSEW

personal crimes such as, theft from the person, have shown smaller decreases; 1.6% of adults experienced theft from the person in 1995 compared with 0.9% in the 2014/15 survey

The levels of victimisation experienced by children aged 10 to 15 years shows a higher level than adult victimisation rates for all crime types in 2014/15 (Figure 1.11). This is because data from the CSEW show that crimes against 10 to 15 year olds are different in nature compared with those against adults. For example, the majority of personal theft offences against children were carried out by a pupil at their school (65%) or a friend (26%), and took place in or around school (62%). The ‘Nature of Crime’ tables accompanying this release have further detail on the data contained within this section.

Figure 1.11: Property crime victimisation, year ending December 1995 and year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Vehicle-related theft victimisation rates relate to vehicle-owning households only

- Bicycle theft victimisation rates relate to bicycle-owning households only

- Data for 1995 are unavailable for children aged 10 to 15

Download this image Figure 1.11: Property crime victimisation, year ending December 1995 and year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

.png (21.2 kB) .xls (30.7 kB)Notes for levels of victimisation

- Personal theft includes: theft from the person (stealth theft, snatch theft and attempted snatch or stealth theft) and ‘other’ theft of personal property, but also theft from inside and outside a dwelling and theft of bicycles where the property stolen belonged solely to the child respondent.

12. Characteristics associated with being a victim of property crime

Analysis has been conducted on the 2014/15 Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) on the characteristics associated with being a victim of property crime. Some of the characteristics may be closely associated with each other, so caution is needed in the interpretation of the effect of these different characteristics when viewed in isolation, (for example employment and household income are closely related). The following is a summary of some household and personal characteristics where there was variation observed in the likelihood of being a victim of property crimes. Appendix tables 1.01-1.11 (386 Kb Excel sheet) contain victimisation data broken down according to a broad range of household and personal characteristics.

Similar to previous findings from previous years some general patterns in victimisation, common across many types of property crime, were seen in the 2014/15 CSEW:

those in younger age groups were more likely to be victims than those in older age groups for most property crime types (the exceptions were plastic card fraud and criminal damage)

levels of victimisation were similar for men and women for most crime types; one exception was robbery where men had higher rates1

while the differences were not statistically significant, there was a pattern across almost all offence types where those who were unemployed appeared more likely to be victims compared with those in employment or who were economically inactive2 (the exceptions were plastic card fraud and criminal damage)

those living in urban areas were more likely to be victims than those living in rural areas for all property crime types with the exception of plastic card fraud

respondents living in the most deprived output areas (based on employment deprivation3) were most likely to be victims of household property crime offences such as burglary, vehicle-related theft and bicycle theft; in contrast, those living in the least deprived areas were more likely to be victims of plastic card fraud

Other victim characteristics vary across different types of property crime. This section summarises the main findings for specific crime types.

Plastic card fraud

The characteristics of plastic card fraud victims were different from other types of property crime in many respects. In particular:

the likelihood of victimisation did not vary significantly by age with the exception of those over 75 (2.0%) who were less likely to be victims than all other age categories (for example, 5.6% of 35 to 44 year old were victims of plastic card fraud)

those living in rural areas (4.7%) had a similar likelihood of victimisation compared with those living in urban areas (4.6%)

those living in the most deprived output areas (4.0%) were less likely to be victims than those living in the least deprived output areas (5.5%)

those in employment (5.1%) were more likely to be a victim compared with those who were unemployed (4.3%) or economically inactive2 (3.8%), and victimisation was greater in higher-income households (for example 6.4% of households with a total income of £50,000 or more compared with 3.4% of households with an income of less than £10,000)

Bicycle theft

bicycle-owning households where the reference person was a full-time student were more likely to be victims of bicycle theft (7.9%) than those in other occupations or who were unemployed (though not all differences were statistically significant)

respondents in lower-income households (for example, 5.1% of bicycle-owning households with a total income of less than £10,000) were more likely to be victims than respondents in higher-income households (for example, 2.5% of bicycle-owning households with a total income of £50,000 or more)

respondents living in bicycle-owning households in areas of high incivility4 (5.8%) were more likely to be victims of bicycle theft than those living in bicycle-owning households in areas of low incivility (2.5%)

Domestic burglary

lone-parent households (4.9%) were more likely to be victims of domestic burglary than adults with children households (2.9%) and households without children (2.5%)

households in areas with high incivility4 (4.2%) were more likely to be victims of burglary than those living in areas with low incivility (2.6%)

Theft from the person

- full-time students (1.9%) were more likely to be victims of theft from the person than those in other occupations

Notes for characteristics associated with being a victim of property crime

Levels of victimisation also varied for other household theft where females had higher rates compared to men.

People who are not in employment or unemployed (people without a job who have not actively sought work in the 4 weeks prior to their interview and/or are not available to start work in the two weeks following their interview) including, for example: students, unpaid carers and retirees.

Data are available for England only. There is more information on the employment deprivation indicator, in Section 7.1 of the User Guide to Crime Statistics for England and Wales.

A physical disorder measure is based upon a CSEW interviewer’s assessment of the level of: (a) vandalism, graffiti and deliberate damage to property; (b) rubbish and litter; and (c) homes in poor condition in the area.

13. Mobile phone ownership and theft

Since 2005/06, the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) has asked respondents about every household member’s ownership of mobile phones and their experience of mobile phone theft. Data on CSEW mobile phone ownership and theft are shown in Appendix Tables 1.12-1.15 (386 Kb Excel sheet).

Theft

According to the 2014/15 CSEW, 1.2% (equivalent to 538,000 people) of mobile phone owners experienced a theft in the previous year a decrease from 1.7% in 2013/14.

Between 2005/06 (when measurement began on the CSEW) and the 2008/09 survey, levels of mobile phone theft showed a fairly flat trend, but this was followed by a fall between 2008/09 and 2009/10 (from 2.1% to 1.7%). Since then levels have remained at a similar level until the latest 0.5 percentage point decrease in 2014/15 (Figure 1.12).

Figure 1.12: Proportion of individual mobile phone owners experiencing theft in the last year, year ending March 2006 to year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Information on mobile phone theft was collected about the respondent and all other members of the household

Download this chart Figure 1.12: Proportion of individual mobile phone owners experiencing theft in the last year, year ending March 2006 to year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Image .csv .xlsThe trend in prevalence of mobile phone theft since CSEW measurement began in 2005/06 is similar for males and females. In the 2014/15 CSEW, 1.2% of males and 1.1% of females had their mobile phone stolen in the last year, equivalent to around 278,000 males and 257,000 females.

According to the 2014/15 CSEW, teenagers and young adult mobile phone owners (those aged 18 to 24) were more likely than other age groups to have had their mobile phone stolen (18 to 21: 3.0%; 22 to 24: 2.4%). Children under 10 (0.4%), adults aged 65 to 74 (0.4%) and adults aged 75 or older (0.2%) who own a mobile phone were least likely to have had their phone stolen.

It is not clear what caused the fall in mobile phone theft prevalence between the 2008/09 and 2009/10 surveys, although they cover a period relatively soon after a charter was launched by the Mobile Industry Crime Action Forum (at the end of 2006) where the majority of mobile phones would be blocked (and hence unusable) within 48 hours of being reported stolen making them less desirable to criminals. The latest 0.5 percentage point decrease (representing a reduction of 246,000 victims) in the prevalence of mobile phone theft compared to 2013/14 may, be partly explained by improvements to mobile phone security and theft prevention. It has been suggested that the release of a new operating system for mobile devices (iOS7) in September 2013, that introduced enhancements in security, is likely to have contributed to the reduction in mobile phone thefts.

The Home Office research paper ‘Reducing mobile phone theft and improving security’ published on 7 September 2014 provides further information on mobile phone ownership and theft, using results from the CSEW and London-specific data from the Metropolitan Police. The London-specific analysis showed that some brands and types of mobile phone, such as smartphones, were more likely to be stolen than others. There are several factors that are likely to affect this, from how desirable a phone is, including its potential resale in second hand markets, to how easy it is to steal the personal data contained within it.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys14. Nature of CSEW property crime

There is further detail on the data contained in the ‘Nature of Crime’tables accompanying this release.

Timing

The 2014/15 CSEW showed that property crimes happened mostly in the evening or night1 (ranging from 40% to 82% of incidents depending on the property crime type) (Figure 1.13). Exceptions to this general pattern were ‘other’ theft of personal property and theft from the person, which were more likely to happen in the daytime (both 60% of incidents respectively). Incidents of robbery were more likely to occur during the night-time (58%) than the daytime (42%). As might be expected, the majority of thefts experienced by children aged 10 to 15 took place during daylight2 hours (91%).

Figure 1.13: Time during day when incidents of property crime occurred, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Morning/afternoon is from 6:00am to 6:00pm; afternoon is from noon (12:00pm) to 6:00pm

- Evening/night is from 6:00pm to 6:00am; night is midnight (12:00am) to 6:00am

Download this chart Figure 1.13: Time during day when incidents of property crime occurred, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Image .csv .xlsLooking at days of the week when offences take place (Figure 1.14), the timing of victimisation is similar across all crime types for domestic burglary, domestic burglary in a non-connected dwelling, ‘other’ household theft, vehicle-related theft, bicycle theft, criminal damage, robbery, theft from the person and ‘other’ theft of personal property. The likelihood of being a victim of the above crime types was higher during a week day compared with a weekend day. Looking at these crimes, between 58% and 72% of incidents occurred during the week (this is equivalent to 13% and 16% per week day3) and between 28% and 42% of incidents occurred during the weekend (this is equivalent to 11% and 17% per weekend day4).

Criminal damage and theft from the person have the lowest proportions of incidents occurring during the week at 58% and the highest proportions of incidents occurring during the weekend at 42%.

In the 2014/15 CSEW, 86% of incidents of theft from children aged 10 to 15 occurred during the week (equivalent to 19% per week day) and 14% of incidents occurred during the weekend (equivalent to 6% per weekend day). This means that the likelihood of a child aged 10 to 15 being a victim of theft is much higher during the week and reflects the fact that a large proportion of incidents occurred in or around school (62%) (‘Nature of crime’ table 10.1).

Figure 1.14: Time during week when incidents of property crime occurred, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Weekend is from Friday 6:00pm to Monday 6:00am

Download this chart Figure 1.14: Time during week when incidents of property crime occurred, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Image .csv .xlsLocation

In the 2014/15 CSEW incidents of vehicle-related theft, criminal damage to a vehicle and bicycle theft most often occurred at or nearby the victim’s home (77%, 75% and 68% respectively) (Figure 1.15). Looking in more detail at the location of these incidents (‘Nature of Crime’ tables 4.2, 5.2, and 8.2), bicycle theft was most likely to occur in a semi-private5 location nearby the victim’s home (53% of incidents), while criminal damage to a vehicle was most likely to occur in the street outside the victim’s home (51% of incidents). Vehicle-related theft was almost equally likely to occur in the street outside the victim’s home (39% of incidents) or in a semi-private location nearby the victim’s home (35% of incidents).

Figure 1.15: Location of where incidents of property crime occurred, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1.15: Location of where incidents of property crime occurred, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

Image .csv .xlsItems stolen

Table 1.2 shows the items most commonly stolen in different types of property crime where a theft was involved.

The 2014/15 CSEW found that jewellery and watches were the items most commonly stolen in incidents of domestic burglary in a dwelling (43%).

Cash and foreign currency6 was the most commonly stolen item in incidents of robbery (44%) and mobile phones were the most commonly stolen item in incidents of theft from the person (51%) (‘Nature of Crime’ tables 3.6 and 7.3).

Results from the 2014/15 CSEW showed that in incidents of theft from vehicles, the items most commonly stolen were exterior fittings (for example, hub caps, wheel trims, number plates); stolen in 33% of incidents. Car radios were stolen in a much lower proportion of thefts from vehicles in the 2014/15 CSEW (2%) compared with the 2005/06 survey (20%). Conversely, according to the 2014/15 CSEW, electrical equipment was stolen in 18% of incidents, higher than in the 2005/06 (3%). This reflects the changing value of such goods and of the emergence of new consumer electronics, mobile telephones and computing (such as satellite navigation systems), which have become more attractive to criminals (‘Nature of Crime’ table 4.5 (251 Kb Excel sheet)).

Table 1.2: Item most commonly stolen in incidents of property crime, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

| England and Wales | ||

| Households/adults aged 16 and over / children aged 10 to 15 | ||

| Property crime type | Item most commonly stolen | Proportion of incidents where item was stolen (%) |

| Theft from the person1 | Mobile phone | 51 |

| Theft from outside a dwelling | Garden furniture | 45 |

| Robbery1 | Cash / foreign currency | 44 |

| Domestic burglary in a dwelling1 | Jewellery / watches | 43 |

| Domestic burglary in a non-connected building to a dwelling1 | Tools / work materials | 40 |

| Theft from a dwelling | Purse / wallet / money / cards | 35 |

| Theft from vehicles1 | Exterior fittings | 33 |

| Other theft of personal property | Cash / foreign currency | 30 |

| Personal theft (children aged 10 to 15) | Mobile phone | 19 |

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | ||

| Notes: | ||

| 1. Where an item was stolen (excludes attempts). | ||

Download this table Table 1.2: Item most commonly stolen in incidents of property crime, year ending March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales

.xls (27.6 kB)The 2014/15 survey showed that mobile phones were the most commonly stolen items in incidents of theft experienced by children aged 10 to 15 (stolen in 19% of incidents). Cash and foreign currency were stolen in 16% of incidents and clothing was stolen in 11% of incidents (‘Nature of Crime’ table 10.6 (102.5 Kb Excel sheet)).

Emotional impact on victims

Property crime does not generally result in physical injury to the victim7; one possible exception to this is robbery, which by definition involves the use or threat of force or violence. However, the emotional impact can still be considerable for victims. The ‘Nature of Crime’ tables 3.10, 4.7, 5.4, 6.4, 7.5, 8.5, and 9.4 provide estimates on the proportion of victims emotionally affected by the result of property crimes.

Perceived seriousness

Respondents who were victims of property crime were asked to rate the seriousness of the crime, with a score of 1 being the least serious and 20 being the most. The ‘Nature of Crime’ tables 3.11, 4.8, 5.5, 6.5, 7.6, 8.6, and 9.5 provide estimates on the perceived seriousness of the property crimes.

Offender profile

For certain crime types, it is possible to provide further information on the characteristics of offenders. According to the 2014/15 CSEW, the victim was able to say something about the offender(s) in 96% of incidents of robbery, 44% of incidents of domestic burglary, 26% of criminal damage incidents and in 51% of thefts of personal property experienced by children aged 10 to 15. There is more detailed information on the characteristics of offenders for the above crime types in ‘Nature of Crime’ tables: 9.1, 3.9, 8.7 and 10.3.

Notes for nature of CSEW property crime

Evening is from 6:00pm to midnight (12:00am); night is midnight (12:00am) to 6:00am.

Daylight (morning) is from 6am to noon (12:00pm); and (afternoon) from noon (12:00pm) to 6:00pm.

Daily data are calculated from the weekly total with the week classified at 6:00am Monday until 6:00pm Friday.

Daily data are calculated from the weekend total with the weekend classified as 6:00pm Friday until 6:00am Monday.

'Semi-private' includes outside areas on or near the premises and garages or car parks around, but not connected to the home.

For personal theft offences (robbery, theft from the person and ‘other’ theft of personal property) ‘Purse/wallet’, ‘Cash/foreign currency’ and ‘Credit cards’ are separate stolen item categories; for household theft offences (domestic burglary and ‘other’ household theft) they have been combined into one stolen item category: ‘Purse/wallet/money/cards’.

CSEW offences are coded according to the Home Office Principal Crime Rule, where if the sequence of crimes in an incident contains more than one type of crime, then the most serious is counted. For example, if the respondent was seriously wounded during the course of a burglary this would be recorded as a violent crime, however if the respondent was assaulted but not seriously wounded this would be recorded as a burglary.

15. Property crime against businesses

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is restricted to crimes experienced by the population resident in households in England and Wales, so doesn’t cover crime against commercial victims. While police recorded crime does include crimes against businesses, it does not separate these out from other crimes (other than for robbery of business property and offences of shoplifting which, by their nature, are against businesses) and only includes crimes reported to and recorded by the police.

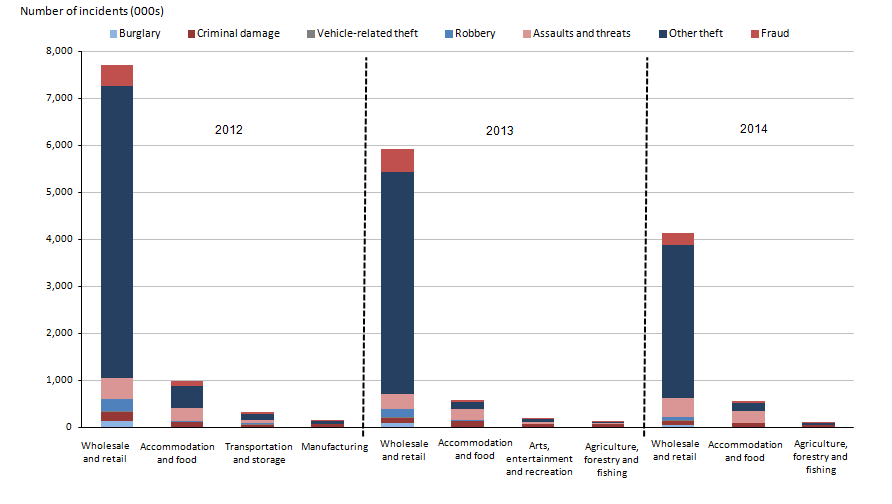

The Commercial Victimisation Survey (CVS) is a telephone survey in which respondents from a representative sample of business premises in certain sectors in England and Wales are asked about crimes experienced at their premises in the 12 months prior to interview. Surveys took place in 2012, 2013 and 2014, having previously run in 1994 and 2002, and work is currently underway on the 2015 CVS.

The 2012 CVS provided information on the volume and type of crime committed against businesses in England and Wales across four sectors: ‘manufacturing’; ‘wholesale and retail’; ‘transportation and storage’; and ‘accommodation and food’. There is more information in the Home Office’s ‘Headline findings from the 2012 Commercial Victimisation Survey’ and ‘Detailed findings from the 2012 Commercial Victimisation Survey’.

The 2013 CVS covered a slightly different set of business sectors; it continued to include the ‘accommodation and food’, and ‘wholesale and retail’ sectors, but the ‘manufacturing’ and ‘transportation and storage’ sectors were replaced by the ‘agriculture, forestry and fishing’ and the ‘arts, entertainment and recreation’ sectors. There is more information in the Home Office’s ‘Headline findings from the 2013 Commercial Victimisation Survey‘ and ‘Detailed findings from the 2013 Commercial Victimisation Survey’.

The 2014 CVS covered ‘wholesale and retail’, ‘accommodation and food’ and ‘agriculture, forestry and fishing’ sectors only (‘arts, entertainment and recreation’, ‘manufacturing’ and ‘transportation and storage’ were not included). In 2014 the wholesale and retail sector had a boosted sample of over 2,000 premises which is around double the usual sample of 1,000 premises for each business sector. There is more information in the Home Office’s ‘Headline findings from the 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey‘ and ‘Findings from the 2014 CVS: confidence intervals and comparisons with 2012 and 2013 CVS’.

Results from the 2012, 2013 and 2014 CVS

It should be noted that the following totals from the CVS represent a small proportion of all crimes experienced by businesses. Direct comparisons in all sectors are not possible due to different sectors being sampled each year.

2012 CVS data estimated that there were 9.2 million crimes against business in the 4 sectors covered by the survey in the year prior to interview; of these 91% were property related (Figure 1.16).

2013 CVS data estimated that there were 6.8 million crimes against business in the 4 sectors covered by the survey in the year prior to interview; of these, 91% were property related (Figure 1.16).

2014 CVS data estimated that there were 4.8 million crimes against business in the 3 sectors covered by the survey in the year prior to the interview; of these, 86% were property related (Figure 1.16).

Figure 1.16: Crime experienced by businesses for selected sectors in England and Wales, year ending December 2012, 2013 and 2014

Source: 2012, 2013 and 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey, Home Office

Notes:

- Property crime figures in the CVS include all crime types in Figure 1.16 except ‘assaults and threats’