Cynnwys

- Main points

- Overview

- Understanding crime statistics

- Summary

- Violent crime

- Robbery

- Sexual offences

- Offences involving knives and sharp instruments

- Offences involving firearms

- Theft offences

- Theft offences - burglary

- Theft offences – vehicle

- Theft offences – other theft of property

- Criminal damage

- Other crimes against society

- Fraud

- Crime experienced by children aged 10 to 15

- Anti-social behaviour

- Other non-notifiable crimes

- Commercial Victimisation Survey

- Data sources – coverage and coherence

- Accuracy of the statistics

- Users of Crime Statistics

- International and UK comparisons

- List of products

- References

- Background notes

- Methodoleg

1. Main points

Latest figures from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) showed that, for the offences it covers, there were an estimated 6.8 million incidents of crime against households and resident adults (aged 16 and over). This is a 7% decrease compared with the previous year’s survey, and the lowest estimate since the CSEW began in 1981

The decrease in all CSEW crime was driven by a reduction in the all theft offences category (down 8%). Within this group there were falls in the sub-categories of theft from the person (down 21%) and other theft of personal property (down 22%). However, there was no significant change in other sub-categories such as domestic burglary and vehicle-related theft

In contrast to the CSEW, there was a 3% increase in police recorded crime compared with the previous year, with 3.8 million offences recorded in the year ending March 2015

The rise in the police figures was driven by increases in violence against the person offences (up by 23% compared with the previous year). However, this increase is thought to reflect changes in recording practices rather than a rise in violent crime. The CSEW estimate for violent crime showed no change compared with the previous year’s survey, following decreases over the past 4 years

Offences involving knives and sharp instruments increased by 2% in the year ending March 2015. This small rise masked more significant changes at offence level with an increase in assaults (up 13%, from 11,911 to 13,488) and a decrease in robberies (down 14%, from 11,927 to 10,270). In addition, the related category of weapon possession offences also rose by 10% (from 9,050 to 9,951). Such serious offences are not thought to be prone to changes in recording practice

Sexual offences recorded by the police rose by 37% with the numbers of rapes (29,265) and other sexual offences (58,954) being at the highest level since the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard in 2002/03. As well as improvements in recording, this is also thought to reflect a greater willingness of victims to come forward to report such crimes. In contrast, the latest estimate from the CSEW showed no significant change in the proportion of adults aged 16-59 who reported being a victim of a sexual assault (including attempted assaults) in the last year (1.7%)

While other acquisitive crimes recorded by the police continued to decline there was an increase in the volume of fraud offences recorded by Action Fraud (up 9%) largely driven by increases in non-investment fraud (up 15%) – a category which includes frauds related to online shopping and computer software services. This is the first time a year-on-year comparison can be made on a like for like basis. It is difficult to know whether this means actual levels of fraud rose or simply that a greater proportion of victims reported to Action Fraud. However, other sources also show year on year increases, including data supplied to the National Fraud Investigation Bureau from industry sources (up 17%)

2. Overview

This release provides the latest statistics on crime from the Crime Survey for England and Wales and police recorded crime.

In accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007, statistics based on police recorded crime data have been assessed against the Code of Practice for Official Statistics and found not to meet the required standard for designation as National Statistics. The full assessment report can be found on the UK Statistics Authority website. Alongside this release, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) have published a progress update on actions taken in addressing the requirements set out by the Authority. Data from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) continue to be badged as National Statistics.

Further information on the datasets is available in the ‘Data sources – coverage and coherence’ section and the CSEW technical report (839.6 Kb Pdf) .

The user guide (1.36 Mb Pdf) to crime statistics for England and Wales provides information for those wanting to obtain more detail on crime statistics. This includes information on the datasets used to compile the statistics and is a useful reference guide with explanatory notes regarding updates, issues and classifications.

The quality and methodology report sets out detailed information about the quality of crime statistics and the roles and responsibilities of the different departments involved in the production and publication of crime statistics.

Last year, revised survey weights and a back-series were produced for the CSEW following the release of the new-2011 Census-based population estimates. For more information see: Presentational and methodological improvements to National Statistics on the Crime Survey for England and Wales.

An interactive guide provides a general overview of crime statistics.

A short video provides an introduction to crime statistics, including an overview of the main data sources used to produce the statistics.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Understanding crime statistics

This quarterly release presents the most recent crime statistics from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW; previously known as the British Crime Survey), and police recorded crime. Neither of these sources can provide a picture of total crime.

Crime survey for England and Wales

The CSEW is a face-to-face victimisation survey in which people resident in households in England and Wales are asked about their experiences of a selected number of offences in the 12 months prior to the interview. It covers adults aged 16 and over, and a separate survey is used to cover children aged 10 to 15, but neither cover those living in group residences (such as care homes, student halls of residence and prisons), or crimes against commercial or public sector bodies. For the population and offence types it covers, the CSEW is a valuable source for providing robust estimates on a consistent basis over time.

It is able to capture offences experienced by those interviewed, not just those that have been reported to, and recorded by, the police. It covers a broad range of victim-based crimes experienced by the resident household population. However, there are some serious but relatively low volume offences, such as homicide and sexual offences, which are not included in its main estimates. The survey also currently excludes fraud and cyber crime though there is ongoing development work to address this gap – the update paper ‘Extending the CSEW to include fraud and cyber crime (113.5 Kb Pdf)' has more information.

Recent research has questioned the ‘capping’ of counts of repeat victimisation in the production of CSEW estimates. A separate methodological note ‘High frequency repeat victimisation in the CSEW' sets out background information on the use of capping and outlines work ONS is doing to review the use of it.

An infographic looking at the people and crimes covered by the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) was published in October 2014.

Police recorded crime

Police recorded crime figures cover selected offences that have been reported to and recorded by the police. They are supplied by the 43 territorial police forces of England and Wales, plus the British Transport Police, via the Home Office, to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The coverage of police recorded crime is defined by the Notifiable Offence List (NOL)1, which includes a broad range of offences, from murder to minor criminal damage, theft and public order offences. The NOL excludes less serious offences that are dealt with exclusively at magistrates’ courts.

Police recorded crime is the primary source of sub-national crime statistics and relatively serious, but low volume, crimes that are not well measured by a sample survey. It covers victims (for example, residents of institutions and tourists) and sectors (for example, commercial bodies) excluded from the CSEW sample. While the police recorded crime series covers a wider population and a broader set of offences than the CSEW, crimes that don’t come to the attention of the police or are not recorded by them, are not included.

Statistics based on police recorded crime data don’t currently meet the required standard for designation as National Statistics (this is explained in the ‘Recent assessments of crime statistics and accuracy’ section).

We also draw on data from other sources to provide a more comprehensive picture of crime and disorder, including incidents of anti-social behaviour recorded by the police and other transgressions of the law that are dealt with by the courts, but not covered in the recorded crime collection.

Recent assessments of crime statistics and accuracy

Following an assessment of ONS crime statistics by the UK Statistics Authority, published in January 2014, the statistics based on police recorded crime data have been found not to meet the required standard for designation as National Statistics. Data from the CSEW continue to be designated as National Statistics.

In their report, the UK Statistics Authority set out 16 requirements to be addressed in order for the statistics to meet National Statistics standards. We are working in collaboration with the Home Office Statistics Unit and Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) to address these requirements. A summary of progress so far is available on the crime statistics methodology page.

In light of concerns raised about the quality of police recorded crime data, in November 2014 we launched a user engagement exercise to help expand our knowledge of users’ needs. The exercise has now closed and a summary of responses was published in May 2015. A short summary of the main themes raised by respondents is given in the ‘Users of Crime Statistics’ section.

As part of the inquiry by the Public Administration Select Committee (PASC) into crime statistics, allegations of under-recording of crime by the police were made. During 2014, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) carried out a national inspection of crime data integrity. The final report Crime-recording: making the victim count, was published on 18 November 2014.

Based on an audit of a large sample of records, HMIC concluded that, across England and Wales as a whole, an estimated 1 in 5 offences (19%) that should have been recorded as crimes were not. The greatest levels of under-recording were seen for violence against the person offences (33%) and sexual offences (26%), however there was considerable variation in the level of under-recording across the different offence types investigated (for example, burglary; 11%) and these are reported on further in the relevant sections.

The audit sample was not large enough to produce compliance rates for individual police forces. However, HMIC inspected the crime recording process in each force and have reported on their findings in separate crime data integrity force reports.

Further information on the accuracy of the statistics is also available in the ‘Accuracy of the statistics’ section.

Time periods covered

The latest CSEW figures presented in this release are based on interviews conducted between April 2014 and March 2015, measuring experiences of crime in the 12 months before the interview. Therefore, it covers a rolling reference period with, for example, respondents interviewed in April 2014 reporting on crimes experienced between April 2013 and March 2014, and those interviewed in March 2015 reporting on crimes taking place between March 2014 and February 2015. For that reason, the CSEW tends to lag short-term trends.

Recorded crime figures relate to crimes recorded by the police during the year ending March 20152 and, therefore, are not subject to the time lag experienced by the CSEW. Recorded crime figures presented in this release are those notified to the Home Office and that were recorded in the Home Office database on 4 June 2015.

There is a 9 month overlap of the data reported here with the data contained in the previous bulletin; as a result the estimates in successive bulletins are not from independent samples. Therefore, year-on-year comparisons are made with the previous year; that is, the 12 month period ending December 2013 (rather than those published last quarter). To put the latest dataset in context, data are also shown for the year ending March 2010 (around five years ago) and the year ending March 2005 (around ten years ago). Additionally, for the CSEW estimates, data for the year ending December 1995, which was when crime peaked in the CSEW (when the survey was conducted on a calendar year basis), are also included.

Users should be aware that improvements in police recording practices following the recent PASC enquiry that took place during late 2013 and HMIC audits of individual police forces which continued until August 2014 are known to have impacted on recorded crime figures. The scale of the effect on both the 2013-14 data and the 2014-15 data is likely to differ between police forces and be particularly driven by the timing of individual forces’ HMIC audit and the timetable by which they introduced any changes.

Notes for understanding crime statistics

The Notifiable Offence List includes all indictable and triable-either-way-offences (offences which could be tried at a crown court) and a few additional closely related summary offences (which would be dealt with by magistrates’ courts). Appendix 1 of the User Guide has more information on the classifications used for notifiable crimes recorded by the police.

Police recorded crime statistics are based on the year in which the offence was recorded, rather than the year in which it was committed. However, such data for any given period will include some historic offences that occurred in a previous year to the one in which it is reported to the police.

4. Summary

Latest headline figures from the CSEW and police recorded crime

Latest figures from the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) show there were an estimated 6.8 million incidents of crime against households and resident adults (aged 16 and over) in England and Wales for the year ending March 2015 (Table 1). This is a 7% decrease from 7.3 million incidents estimated in the previous year’s survey and continues the long term downward trend seen since the mid-1990s. The latest estimate is the lowest since the survey began in 1981. The total number of CSEW incidents is 27% lower than the 2009/10 survey estimate and 64% lower than its peak level in 1995.

Crime covered by the CSEW increased steadily from 1981, before peaking in 1995. After peaking, the CSEW showed marked falls up until the 2004/05 survey year. Since then, the underlying trend has continued downwards, but with some fluctuation from year to year (Figure 1).

An interactive version of Figure 1 is also available.

The CSEW covers a broad range of, but not all, victim-based crimes experienced by the resident household population, including those which were not reported to the police. However, there are some serious but relatively low volume offences, such as homicide and sexual offences, which are not included in its headline estimates. The survey also currently excludes fraud and cyber crime though there is ongoing development work to address this gap (the update paper ‘ Extending the CSEW to include fraud and cyber crime (113.5 Kb Pdf) ' contains more information). This infographic looking at the people and crimes covered by the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) provides more information on what is and is not included in the CSEW.

Figure 1: Trends in police recorded crime and Crime Survey for England and Wales, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015 [1,2]

![Figure 1: Trends in police recorded crime and Crime Survey for England and Wales, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015 [1,2]](/resource?uri=/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/2015-07-16/cdf1692d.png)

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics / Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

- Prior to the year ending March 2002, CSEW respondents were asked about their experience of crime in the previous calendar year, so year-labels identify the year in which the crime took place. Following the change to continuous interviewing, respondents’ experience of crime relates to the full 12 months prior to interview (i.e. a moving reference period). Year-labels for year ending March 2002 identify the CSEW year of interview

- CSEW data relate to households/adults aged 16 and over

- Some forces have revised their data and police recorded crime totals may not agree with those previously published

Download this image Figure 1: Trends in police recorded crime and Crime Survey for England and Wales, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015 [1,2]

.png (31.1 kB) .xls (92.7 kB)The CSEW time series shown in Figure 1 doesn't include crimes committed against children aged 10 to 15. The survey was extended to include such children from January 2009: data from this module of the survey are not directly comparable with the main survey. The CSEW estimated that 709,000 crimes1 were experienced by children aged 10 to 15 in the year ending March 2015. Of this number, 53% were categorised as violent crimes2 (373,000), while most of the remaining crimes were thefts of personal property (278,000; 39%). Incidents of criminal damage to personal property experienced by children were less common (59,000; 8% of all crimes). The proportions of violent, personal property theft and criminal damage crimes experienced by children aged 10 to 15 are similar to the previous year (55%, 40% and 5% respectively).

Police recorded crime is restricted to offences that have been reported to and recorded by the police, and so doesn’t provide a total count of all crimes that take place. The police recorded 3.8 million offences in the year ending March 2015, an increase of 3% compared with the previous year (Table 2)3. Of the 44 forces (including the British Transport Police), 29 showed an annual increase in total recorded crime which was largely driven by rises in the volume of violence against the person offences. This increase in police recorded crime needs to be seen in the context of the renewed focus on the quality of crime recording and the 7% decrease estimated by the CSEW.

Like CSEW crime, police recorded crime also increased during most of the 1980s and then fell each year from 1992 to 1998/99. Expanded coverage of offences in the police recorded crime collection, following changes to the Home Office Counting Rules (HOCR) in 1998, and the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in April 2002, saw increases in the number of crimes recorded by the police while the CSEW count fell. Following these changes, trends from both series tracked each other well from 2002/03 until 2006/07. While both series continued to show a downward trend between 2007/08 and 2012/13, the gap between them widened with police recorded crime showing a faster rate of reduction (32% compared with 19% for the CSEW, for a comparable basket of crimes)4.

More recently this pattern for the comparable basket of crimes has changed, with overall police recorded crime now showing a small increase over the past year, while CSEW estimates have continued to fall, albeit at a slower rate. However, the changes in overall crime seen in both sources mask different trends for individual types of crime; for example the increases in violence, sexual offences and fraud in police recorded crime and the flattening out of the previous downward trend in violence estimated by the CSEW.

A likely factor behind the changing trend in police recorded crime is the renewed focus on the quality of recording by the police, in light of the inspections of forces by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC), the Public Administration Select Committee (PASC) inquiry into crime statistics, and the UK Statistics Authority’s decision to remove the National Statistics designation. This renewed focus is thought to have led to improved compliance with the NCRS, leading to a greater proportion of crimes reported to the police being recorded.

Police recorded crime data are presented here within a number of broad groupings, victim-based crime, other crimes against society and fraud. Victim-based crime5 accounted for 83% of all police recorded crime, with 3.2 million offences recorded in the year ending March 2015. This was an increase of 2% compared with the previous year. While there were decreases across many of the police recorded crime categories, these were offset by large increases in both violence against the person offences, which was up by 23% (an additional 144,404 offences), and sexual offences, up by 37% (an additional 23,990 offences).

Other crimes against society6 accounted for 11% of all police recorded crime, with 403,878 offences recorded in the year ending March 2015 (an increase of 1% compared with the previous year). Trends in such offences often reflect changes in police activity and workload, rather than levels of criminality. However, anecdotal evidence from forces suggests that some increases in this grouping, such as those seen in public order offences, are being driven by a tightening of recording practices. Public order offences accounted for the largest volume rise and increased by 19%, miscellaneous crimes against society increased by 15%, offences involving possession of weapons by 6%, but drug offences decreased by 14%.

The remaining 6% of recorded crimes were fraud offences. There were 230,630 fraud offences recorded by Action Fraud in the year ending March 2015 (an increase of 9% on the previous year). This is the first year that these figures are comparable with the previous year, because of the transition to a centralised recording of fraud offences. The ‘Total fraud offences recorded by Action Fraud’ section has further details.

In addition, fraud data are also collected from industry bodies by the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB) but are not currently included in the police recorded crime series. In the year ending March 2015, there were 389,718 reports of fraud to the NFIB from industry bodies, the vast majority of which were related to banking and credit industry fraud. A further 1.3 million cases of fraud on UK-issued cards were reported by FFA UK. The ‘Fraud’ section has more information on these data sources.

Overall level of crime – other sources of crime statistics

Around 2 million incidents of anti-social behaviour (ASB) were recorded by the police for the year ending March 2015. These are incidents that were not judged to require recording as a notifiable offence within the Home Office Counting Rules for recorded crime. The number of ASB incidents in the year ending March 2015 decreased by 8% compared with the previous year. However, it should be noted that a review by HMIC in 2012 found that there was a wide variation in the quality of decision making associated with the recording of ASB. As a result, ASB incident data should be interpreted with caution.

In the year ending December 2014 (the latest period for which data are available) there were over 1 million convictions for non-notifiable offences (up 3% from the year ending December 2013), that are not covered in police recorded crime or the CSEW (for example: being drunk and disorderly; committing a speeding offence). There were 29,000 Penalty Notices for Disorder issued in relation to non-notifiable offences 7.

The CSEW does not cover crimes against businesses and police recorded crime can only provide a partial picture (as not all offences come to the attention of the police). The 2013 Commercial Victimisation Survey and 2014 Commercial Victimisation Survey, respectively, estimated that there were 6.6 million and 4.8 million incidents of crime against business premises8 in England and Wales in the three comparable sectors covered by each survey (‘Wholesale and retail’, ‘Accommodation and food’ and ‘Agriculture, forestry and fishing’).

Trends in victim-based crime – CSEW

The CSEW provides coverage of a broad range of victim-based crimes, although there are necessary exclusions from its main estimates, such as homicide and sexual offences. This infographic has more information on the coverage of the survey.

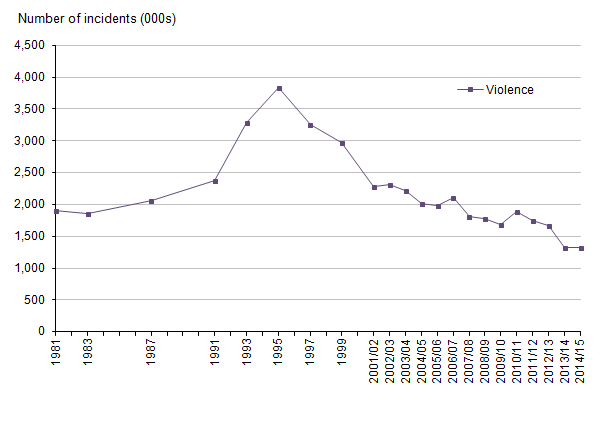

Estimates of violent crime from the CSEW have shown large falls between the 1995 and the 2004/05 survey. Since then the survey shows a general downward trend in violent crime, albeit with some fluctuations (notably in 2010/11), although the year ending March 2015 was flat when compared with the previous twelve months and may indicate a slowing of the previous downward pattern.

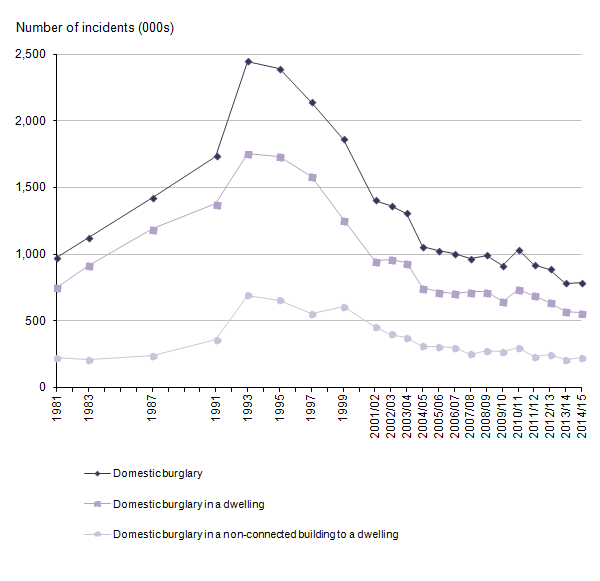

CSEW domestic burglary follows a similar pattern to that seen for all CSEW crime, peaking in the 1993 survey and then falling steeply until the 2004/05 CSEW. The underlying trend in domestic burglary remained fairly flat between the 2004/05 and 2010/11 surveys before further falls in 2012/13 and 2013/14. As a result estimates of domestic burglary for the year ending March 2015 are 26% lower than those in the 2004/05 survey. However, there has been no change in levels of domestic burglary between the 2013/14 and 2014/15 surveys (the apparent year-on-year rise of 1% was not statistically significant).

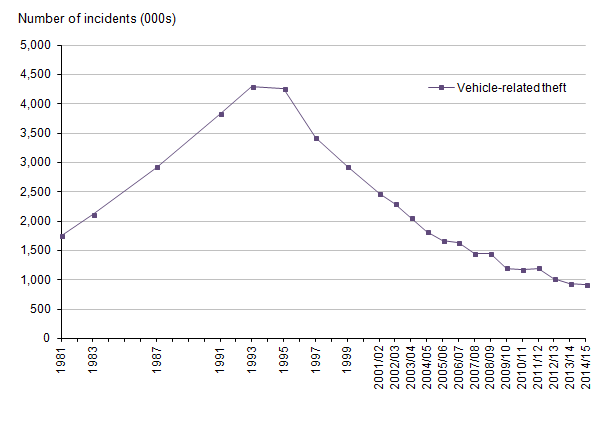

The CSEW category of vehicle-related theft has shown a consistent downward trend since the mid-1990s. However, as with domestic burglary, there was no change in the level of vehicle-related theft in the last year (the apparent decrease of 1% was not statistically significant). The latest estimates indicate that a vehicle-owning household was around 5-times less likely to become a victim of such crime than in 1995.

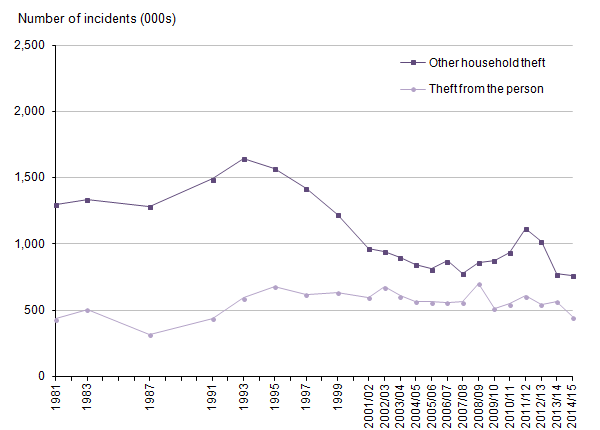

The apparent 2% decrease in CSEW other household theft compared with the previous year was also not statistically significant. The lastest estimates show levels of other household theft slightly lower than those seen in the 2007/08 survey, following a period of year-on-year increases between the 2007/08 and 2011/12 surveys. Peak levels of other household theft were recorded in the mid-1990s and the latest estimate is around half the level seen in 1995.

The CSEW estimates that there were around 741,000 incidents of other theft of personal property in the survey year ending March 2015, a decrease of 22% compared with the previous year. The underlying trend was fairly flat between 2004/05 and 2011/12 following marked declines from the mid-1990s; since 2011/12 estimates have decreased with the latest estimate 22% lower compared with the previous year.

Latest CSEW findings for bicycle theft show little change in the level of incidents in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year (the apparent 2% increase was not statistically significant). Over the long term, incidents of bicycle theft showed a marked decline between 1995 and the 1999 survey, with both small increases and decreases thereafter. Estimates for the year ending March 2015 are now 42% lower than in 1995 but remain similar to the level seen in 1999.

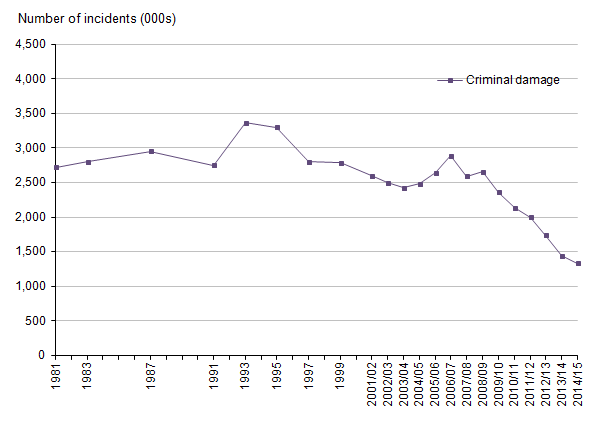

The number of incidents of criminal damage estimated by the CSEW showed little change in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year (the apparent 8% decrease was not statistically significant). The longer term trend shows a period of increasing incidents of criminal damage between 2003/04 and 2006/07 followed by a marked decline from 2008/09 onwards.

CSEW estimates for robbery and theft from the person decreased significantly from the previous year (46% and 21% respectively). These estimates (and particularly those for robbery) must be treated with caution and interpreted alongside police recorded crime as short term trends in these crimes are likely to fluctuate when measured by the CSEW due to the small number of victims interviewed in any one year. However, in the year ending March 2015 police recorded robberies and thefts from the person also decreased (by 13% and 20% respectively). Further information on these crimes is provided in the relevant sections of this bulletin.

Table 1: Number of CSEW incidents for year ending March 2015 and percentage change [1]

| England and Wales | |||||||||

| Adults aged 16 and over/households | |||||||||

| Offence group2 | Apr '14 to Mar '153 Number of incidents (thousands) | April 2014 to March 2015 compared with: | |||||||

| Jan '95 to Dec '95 | Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | ||||||

| % change and significance4 | |||||||||

| Violence | 1,321 | -66 | * | -34 | * | -22 | * | 0 | |

| with injury | 683 | -70 | * | -41 | * | -23 | * | 8 | |

| without injury | 638 | -59 | * | -24 | * | -20 | * | -8 | |

| Robbery | 90 | -74 | * | -64 | * | -72 | * | -46 | * |

| Theft offences | 4,042 | -65 | * | -30 | * | -19 | * | -8 | * |

| Theft from the person | 451 | -34 | * | -21 | * | -12 | -21 | * | |

| Other theft of personal property | 741 | -64 | * | -34 | * | -26 | * | -22 | * |

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 33,350 | ||||||||

| Domestic burglary | 785 | -67 | * | -26 | * | -14 | * | 1 | |

| Domestic burglary in a dwelling | 559 | -68 | * | -25 | * | -14 | * | -2 | |

| Domestic burglary in a non-connected building to a dwelling | 225 | -66 | * | -27 | * | -15 | * | 7 | |

| Other household theft | 760 | -52 | * | -10 | * | -13 | * | -2 | |

| Vehicle-related theft | 923 | -78 | * | -50 | * | -23 | * | -1 | |

| Bicycle theft | 381 | -42 | * | -2 | -19 | * | 2 | ||

| Criminal damage | 1,334 | -60 | * | -46 | * | -43 | * | -8 | |

| Unweighted base - number of households | 33,299 | ||||||||

| All CSEW crime | 6,786 | -64 | * | -36 | * | -27 | * | -7 | * |

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | |||||||||

| Notes: | |||||||||

| 1. More detail on further years can be found in Appendix Table A1 | |||||||||

| 2. Section 5 of the User Guide provides more information about the crime types included in this table | |||||||||

| 3. Base sizes for data since year ending March 2015 are smaller than previous years, due to sample size reductions introduced in April 2012 | |||||||||

| 4. Statistically significant change at the 5% level is indicated by an asterisk | |||||||||

Download this table Table 1: Number of CSEW incidents for year ending March 2015 and percentage change [1]

.xls (33.8 kB)Trends in victim-based crime – police recorded crime

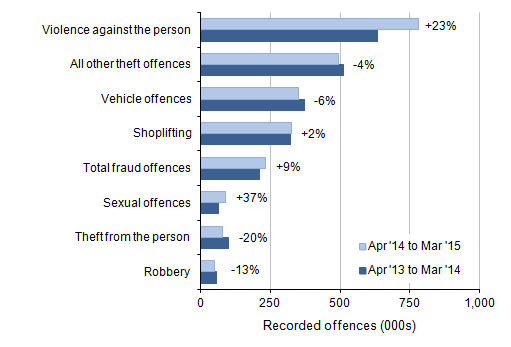

Figure 2 focuses on selected police recorded crime offences with notable changes in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year.

Figure 2: Selected victim-based police recorded crime offences in England and Wales: volumes and percentage change between year ending March 2014 and year ending March 2015

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics.

- ‘All other theft’ includes: theft of unattended items, blackmail, theft by an employee, and making off without payment.

Download this image Figure 2: Selected victim-based police recorded crime offences in England and Wales: volumes and percentage change between year ending March 2014 and year ending March 2015

.png (13.2 kB) .xls (86.0 kB)There was a 2% increase in victim-based crimes in the year ending March 2015 to 3.2 million offences. This is equivalent to 56 recorded offences per 1,000 population (though this shouldn’t be read as a victimisation rate as multiple offences could be reported by the same victim) – shown in Table 3.

The 23% increase in violence against the person offences recorded by the police is likely to be driven by improved compliance with the NCRS as the CSEW showed no change in estimated levels of violence over the same period. The volume of recorded violence against the person crimes (779,027 offences) equates to approximately 14 offences recorded per 1,000 population in the year ending March 2015. The largest increase in total violence against the person offences was in the violence without injury subcategory, which showed an increase of 30% compared with the previous year. The violence with injury subcategory showed a smaller increase (16%) over the same period.

In the year ending March 2015 the police recorded 534 homicides, 1 more than the previous year9. This latest annual count of homicides remains close to the lowest level recorded since 1978 (532 offences). The number of homicides increased from around 300 per year in the early 1960s to over 800 per year in the early years of this century, which was at a faster rate than population growth over that period10. However, over the past decade the volume of homicides has decreased while the population of England and Wales has continued to grow.

Offences involving firearms (excluding air weapons) have recorded almost no change in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year. This has seen a downward trend in previous years, and is over 50% less than it was at its peak in 2005/06. However, the number of offences that involved a knife or sharp instrument showed a small increase (2%) over the past 12 months when compared with the previous year11 and marks the end of the previous general downward trend in these offences. This, however, masked a larger rise in the offence category ‘assault with injury and assault with intent to cause serious harm’ where a knife or sharp instrument was involved (13%) and a reduction in robberies involving a knife or sharp instrument (14%).

Police recorded robberies fell 13% in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year, from 57,828 offences to 50,236 offences. This is equivalent to around 1 offence recorded per 1,000 population and is the lowest level since the introduction of the NCRS in 2002/03 (when 110,271 offences were recorded). With the exception of a notable rise in the number of robberies in 2005/06 and 2006/07, there has been a general downward trend in robbery offences since 2002/03. The overall decrease has been driven by a fall in the number of offences recorded by the Metropolitan Police Force (which decreased by 22% to 21,907 offences). As before, robbery offences tended to be concentrated in large urban areas (nearly half were recorded in London).

Sexual offences recorded by the police increased by 37% compared with the previous year, to a total of 88,219 across England and Wales in the year ending March 2015. Within this, the number of offences of rape increased by 41% and the number of other sexual offences increased by 36%. These rises are the largest year-on-year increases since the introduction of the NCRS in 2002/03. These increases are likely to be due to an improvement in crime recording by the police and an increase in the willingness of victims to come forward and report these crimes to the police. Estimates from the 2014/15 CSEW show a similar level of victimisation rates compared with the previous year. In the year ending March 2015, 1.7% of respondents had been victims of sexual assault or attempted sexual assault in the last year, compared with 1.5% in the year ending March 2014; the ‘Sexual offences’ section has more information.

Previous increases in the number of sexual offences reported to the police were shown to have been related also to a rise in the reporting of historic offences12 following ‘Operation Yewtree’, which began in 2012. Feedback from forces indicates that both current and historic offences (those that took place over 12 months before being reported) continued to rise in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year. However, the major contribution to this increase is believed to have come from current offences.

Total theft offences recorded by the police in the year ending March 2015 showed a 5% decrease compared with the previous year, continuing the year-on-year decrease seen since 2002/03. The majority of the categories in this offence group (burglary, vehicle offences, theft from the person, bicycle theft and ‘all other theft offences’) showed decreases compared with the previous year. One exception to this was shoplifting, which increased by 2% compared with the previous year (from 321,078 offences to 326,464), the highest level since the introduction of the NCRS in 2002/03, although the rate of increase has slowed from the 7% recorded in 2013/14. Vehicle interference has increased by 88% (from 20,367 to 38,229) in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year. A change in the guidance within Home Office Counting Rules (HOCR) in April 2014 is likely to have led to offences that previously might have been recorded as attempted theft of, or from, a vehicle or criminal damage to a vehicle now being recorded as vehicle interference when the motive of the offender was not clear.

Theft from the person offences recorded by the police in the year ending March 2015 showed a 20% decrease compared with the previous year. This is a reversal of recent trends, which showed year-on-year increases between 2008/09 and 2012/13. This latest decrease is thought to be associated with improved mobile phone security features. The ‘Theft offences - Other theft of property’ section has more information.

Fraud offences

Responsibility for recording fraud offences has transferred from individual police forces to Action Fraud. This transfer occurred between April 2011 and March 2013. In the year ending March 2015 there were 230,630 fraud offences recorded by Action Fraud reported to them by victims in England and Wales. This represents a volume increase of 9% compared with the previous year. This is the first time comparable data have been available on a year on year basis, as the transition from police forces to Action Fraud was completed in March 2013 (Appendix Table A5). Thus, the latest figures suggest that while other acquisitive crimes continue to fall, the level of fraud has increased.

Other industry data also show reported fraud is increasing, with 389,718 reports of fraud to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau from industry bodies. One of these bodies, FFA UK, also publishes data on the volume of fraud on UK-issued bank cards. In the 2014 calendar year, they reported 1.3 million cases of such fraud; the ‘Fraud’ section has further information.

However, it is difficult to judge whether or not administrative data reflects changes in actual crime levels or increased reporting from victims. The CSEW data on plastic card fraud shows that, for the year ending March 2015 survey, 4.6% of plastic card owners were victims of card fraud in the last year, a decrease from the year earlier (when 5.1% of card owners were victims). The current level is lower than the peak five years earlier, when 6.4% of card owners were victims.

Table 2: Number of police recorded crimes for year ending March 2015 and percentage change [1,2,3]

| England and Wales | ||||

| Number and percentage change | ||||

| Offence group | Apr '14 to Mar '15 | April 2014 to March 2015 compared with: | ||

| Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | ||

| Victim-based crime | 3,176,760 | -37 | -16 | 2 |

| Violence against the person offences | 779,027 | -8 | 11 | 23 |

| Homicide | 534 | -38 | -14 | 0 |

| Violence with injury4 | 374,216 | -27 | -7 | 16 |

| Violence without injury5 | 404,277 | 23 | 36 | 30 |

| Sexual offences | 88,219 | 45 | 66 | 37 |

| Rape | 29,265 | 109 | 94 | 41 |

| Other sexual offences | 58,954 | 26 | 55 | 36 |

| Robbery offences | 50,236 | -45 | -33 | -13 |

| Robbery of business property | 5,754 | -27 | -30 | -1 |

| Robbery of personal property | 44,482 | -46 | -34 | -15 |

| Theft offences | 1,755,436 | -38 | -18 | -5 |

| Burglary | 411,454 | -40 | -24 | -7 |

| Domestic burglary | 197,021 | -39 | -27 | -7 |

| Non-domestic burglary | 214,433 | -40 | -21 | -7 |

| Vehicle offences | 351,452 | -57 | -29 | -6 |

| Theft of a motor vehicle | 75,809 | -69 | -36 | 1 |

| Theft from a vehicle | 237,414 | -53 | -30 | -14 |

| Interfering with a motor vehicle | 38,229 | -50 | 1 | 88 |

| Theft from the person | 78,814 | -35 | -15 | -20 |

| Bicycle theft | 93,450 | -12 | -15 | -4 |

| Shoplifting | 326,464 | 16 | 6 | 2 |

| All other theft offences6 | 493,802 | -40 | -16 | -4 |

| Criminal damage and arson | 503,842 | -58 | -37 | 0 |

| Other crimes against society | 403,878 | -11 | -20 | 1 |

| Drug offences | 169,964 | 17 | -28 | -14 |

| Trafficking of drugs | 27,026 | 12 | -19 | -8 |

| Possession of drugs | 142,938 | 18 | -29 | -15 |

| Possession of weapons offences | 21,904 | -46 | -24 | 6 |

| Public order offences | 159,528 | -17 | -15 | 19 |

| Miscellaneous crimes against society | 52,482 | -30 | 1 | 15 |

| Total fraud offences7 | 230,630 | 43 | 215 | 9 |

| Total recorded crime - All offences including fraud7 | 3,811,268 | -32 | -12 | 3 |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics | ||||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police) | ||||

| 3. More detail on further years can be found in Appendix Table A4 | ||||

| 4. Includes attempted murder, intentional destruction of viable unborn child, causing death by dangerous driving/careless driving when under the influence of drink or drugs, more serious wounding or other act endangering life (including grievous bodily harm with and without intent), causing death by aggravated vehicle taking and less serious wounding offences | ||||

| 5. Includes threat or conspiracy to murder, harassment, other offences against children and assault without injury (formerly common assault where there is no injury) | ||||

| 6. All other theft offences now includes all 'making off without payment' offences recorded since year ending March 2003. Making off without payment was previously included within the fraud offence group, but following a change in the classification for year ending March 2014, this change has been applied to previous years of data to give a consistent time series | ||||

| 7. Action Fraud have taken over the recording of fraud offences on behalf of individual police forces. The process began in April 2011 and was rolled out to all police forces by March 2013. Due to this change, caution should be applied when comparing data over this transitional period and with earlier years. New offences were introduced under the Fraud Act 2006, which came into force on 15 January 2007 | ||||

Download this table Table 2: Number of police recorded crimes for year ending March 2015 and percentage change [1,2,3]

.xls (34.3 kB)

Table 3: Total police recorded crime - rate of offences [1,2,3]

| Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | Apr '14 to Mar '15 | |

| Rate per 1,000 population | ||||

| Total recorded crime - all offences including fraud | 107 | 79 | 66 | 67 |

| Victim-based crime4 | 95 | 69 | 55 | 56 |

| Other crimes against society | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| Total fraud offences | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics | ||||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police) | ||||

| 3. For detailed footnotes and further years see Appendix table A4 | ||||

| 4. Victim-based crime now includes all 'making off without payment' offences recorded since the year ending March 2003. Making off without payment was previously included within the fraud offence group, but following a change in the classification for the year ending March 2014, this change has been applied to previous years of data to give a consistent time series | ||||

Download this table Table 3: Total police recorded crime - rate of offences [1,2,3]

.xls (29.2 kB)Notes for summary

- The survey of children aged 10 to 15 only covers personal level crime (so excludes household level crime) and, as with the main survey, does not include sexual offences

- The majority (73%) of violent crimes experienced in the year ending March 2015 resulted in minor or no injury, so in most cases the violence is low level

- Police recorded crimes are notifiable offences which are all crimes that could possibly be tried by a jury (these include some less serious offences, such as minor theft that would not usually be dealt with in this way) plus a few additional closely related offences, such as assault without injury

- The methodological note Analysis of variation in crime trends and Section 4.2 of the User Guide have more details

- Victim-based crimes are those offences with a specific identifiable victim. These cover the police recorded crime categories of violence against the person, sexual offences, robbery, theft offences, and criminal damage and arson

- 'Other crimes against society’ cover offences without a direct victim, and includes drug offences, possession of weapon offences, public order offences and miscellaneous crimes against society

- Non-notifiable offences are offences dealt with exclusively by magistrates’ courts or by the police issuing of a Penalty Notice for Disorder or a Fixed Penalty Notice. Along with non-notifiable offences dealt with by the police (such as speeding), these include many offences that may be dealt with by other agencies – for example: prosecutions by TV Licensing; or the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) for vehicle registration offences

- This is a premises based survey: respondents were asked if the business at their current premises had experienced any of a range of crime types in the 12 months prior to interview and, if so, how many incidents of crime had been experienced.

- Homicide includes the offences of murder, manslaughter, corporate manslaughter and infanticide. Figures from the Homicide Index for the time period April 2013 to March 2014, which take account of further police investigations and court outcomes, were published in Focus on: Violent Crime and Sexual Offences, 2013/14 on 12 February 2015

- These figures, taken from the Homicide Index, are less likely to be affected by changes in police recording practices made in 1998 and 2002, so it is possible to examine longer-term trends

- Only selected violent offences can be broken down by whether a knife or sharp instrument was used. These are: homicide; attempted murder; threats to kill; assault with injury and assault with intent to cause serious harm; robbery; rape; and sexual assault

- More information can be found in Crime in England and Wales, Year Ending September 2013

5. Violent crime

Violent crime in the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is referred to as “violence”, and includes wounding and assault (for both completed and attempted incidents). There is also an additional breakdown of violence with, or without injury. Violent offences in police recorded data is referred to as “violence against the person” and includes homicide, violence with injury, and violence without injury. As with the CSEW, attempted assaults are counted alongside completed ones. There are some closely related offences in the police recorded crime series, such as public disorder, that have no identifiable victim and are classified as other offences.

Latest CSEW estimates show there were 1.3 million violent incidents in England and Wales. This shows no significant change compared with last year’s survey, following a period when the underlying trend from the survey was generally downward (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Trends in Crime Survey for England and Wales violence, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Prior to the year ending March 2002, CSEW respondents were asked about their experience of crime in the previous calendar year, so year-labels identify the year in which the crime took place. Following the change to continuous interviewing, respondents’ experience of crime relates to the full 12 months prior to interview (i.e. a moving reference period). Year-labels for year ending March 2002 identify the CSEW year of interview.

- The numbers of incidents are derived by multiplying incidence rates by the population estimates for England and Wales.

Download this image Figure 3: Trends in Crime Survey for England and Wales violence, year ending December 1981 to year ending March 2015

.png (13.2 kB) .xls (87.6 kB)The CSEW subcategories of "violence with injury" and "violence without injury" also showed no change with the apparent changes (with injury up 8% and without injury down 8%) not being statistically significant.

The long-term trends have been downward with the estimate of violent incidents having decreased by 66% from its peak in 1995 (Table 4b). Around 2 in every 100 adults were a victim of violent crime in the last year, based on the year ending March 2015 survey, compared with around 5 in 100 adults in the 1995 survey (Table 4a). However, it is important to note that victimisation rates vary considerably across the population and by geographic area. Such variations in victimisation rates are further explored in both our thematic reports (which are published annually)1, as well as the Annual Trend and Demographic tables, published alongside this report.

Estimates of violence against 10 to 15 year olds as measured by the CSEW can be found in the section ‘Crime experienced by children aged 10 to 15’.

The longer term reduction in violent crime, as shown by the CSEW, is supported by evidence from several health data sources. Research conducted by the Violence and Society Research Group at Cardiff University (Sivarajasingam et al., 2015) shows a downward trend, with findings from their annual survey, covering a sample of hospital emergency departments and walk-in centres in England and Wales, showed an overall decrease of 10% in serious violence-related attendances in 2014 compared with 2013 (down to 211,514 attendances in 2014). In addition, the most recent provisional National Health Service (NHS) data available on assault admissions to hospitals in England show that, for the 12 months to the end of March 2014, there were 31,243 hospital admissions for assault, a reduction of 5% compared with figures for the preceding 12 months2.

Table 4a: CSEW violence - number, rate and percentage of incidents [1]

| England and Wales | |||||

| Adults aged 16 and over | |||||

| Interviews from: | |||||

| Jan '95 to Dec '95 | Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '142 | Apr '14 to Mar '152 | |

| Number of incidents | Thousands | ||||

| Violence | 3,837 | 2,010 | 1,687 | 1,327 | 1,321 |

| with injury | 2,270 | 1,167 | 892 | 632 | 683 |

| without injury | 1,567 | 844 | 795 | 694 | 638 |

| Incidence rate per 1,000 adults | |||||

| Violence | 94 | 48 | 39 | 29 | 29 |

| with injury | 56 | 28 | 20 | 14 | 15 |

| without injury | 39 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 14 |

| Percentage of adults who were victims once or more | Percentage | ||||

| Violence | 4.8 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| with injury | 3.0 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| without injury | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 16,337 | 45,118 | 44,559 | 35,371 | 33,350 |

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Appendix table A1, A2, A3 provide detailed footnotes and data for further years | |||||

| 2. Base sizes for data since the years ending March 2014 and March 2015 are smaller than previous years, due to sample size reductions introduced in April 2012 | |||||

Download this table Table 4a: CSEW violence - number, rate and percentage of incidents [1]

.xls (93.2 kB)

Table 4b: CSEW violence - percentage change and statistical significance [1]

| England and Wales | |||||||

| Adults aged 16 and over | |||||||

| April 2014 to March 2015 compared with: | |||||||

| Jan '95 to Dec '95 | Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | ||||

| Number of incidents | Percentage change and significance2 | ||||||

| Violence | -66 | * | -34 | * | -22 | * | 0 |

| with injury | -70 | * | -41 | * | -23 | * | 8 |

| without injury | -59 | * | -24 | * | -20 | * | -8 |

| Incidence rate per 1,000 adults | |||||||

| Violence | -69 | * | -40 | * | -25 | * | -1 |

| with injury | -73 | * | -46 | * | -27 | * | 7 |

| without injury | -64 | * | -31 | * | -23 | * | -9 |

| Percentage of adults who were victims once or more | Percentage point change and significance2,3 | ||||||

| Violence | -3 | * | -1.1 | * | -0.6 | * | 0.0 |

| with injury | -2 | * | -0.8 | * | -0.4 | * | 0.0 |

| without injury | -1.2 | * | -0.4 | * | -0.3 | * | 0.0 |

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | |||||||

| Notes: | |||||||

| 1. Appendix table A1, A2, A3 provide detailed footnotes and data for further years | |||||||

| 2. Statistically significant change at the 5% level is indicated by an asterisk | |||||||

| 3. The percentage point change presented in the tables may differ from subtraction of the 2 percentages due to rounding | |||||||

Download this table Table 4b: CSEW violence - percentage change and statistical significance [1]

.xls (31.2 kB)The number of violence against the person offences recorded by the police in the year ending March 2015 showed a 23% increase compared with the previous year (up from 634,623 to 779,027, Tables 5a and 5b). There was a much larger increase in the category of “violence without injury” (up 30%) than “violence with injury” (up 16%).

All but one police force recorded a percentage point rise in violence in the year ending March compared with the previous year3, although the forces with the largest percentage increases may not necessarily have had the largest impact on the national figures, since the areas police forces serve can differ greatly in size. It is not surprising that the largest volume increase was reported by the Metropolitan Police Service, which recorded an additional 33,783 offences compared with the previous year (an increase of 26%). Other large volume increases included Greater Manchester Police (up 11,723 offences, an increase of 40%), Hampshire Constabulary (up 7,210, 34%), and Sussex Police (up 6,810, 45%). Northamptonshire Police had the largest percentage change increase, up 53% (or 3,935 offences), followed by Sussex Police (up 45% to 22,008) and Merseyside Police (up 44% to 18,587).

It is known that violent offences are more prone, than some other offences, to subjective judgement about whether or not to record a crime. The Crime-recording: making the victim count report published by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) found that violence against the person offences had the highest under-recording rates across police forces in England and Wales. Nationally, an estimated 1 in 3 (33%) violent offences that should have been recorded as crimes were not. The ‘Accuracy of the statistics’ section has more information.

Action taken by police forces to improve their compliance with the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) is likely to have resulted in the increase in the number of offences recorded4. It is thought that recording improvements are more likely to affect relativelty less serious violent offences and explains the larger increase in the sub-category "violence without injury" compared with "violence with injury". ONS has also been informed there has generally been little change in the volume of “calls for service” related to violent crime in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year. Calls for service refer to emergency and non-emergency calls from members of the public and referrals from partner agencies (such as education, health, and social services) for police to attend an incident or investigate a case. This, along with the evidence from the CSEW, suggests the rise in recorded violence against the person is largely due to process improvements rather than a genuine rise in violent crime.

As well as changes in recording practices, another possible factor behind the rise is an increase in the reporting of domestic abuse and subsequent recording of these offences by the police. An HMIC inspection expressed concerns about the police response to domestic abuse, but noted the majority of Police and Crime Commissioners (PCC) were now showing a strong commitment to tackling this crime. The report noted just under half of PCCs had made a commitment to increase the reporting of this type of offence. It is thought that this renewed focus may have led to more victims coming forward to report crimes and allegations being treated more sensitively.

Recent changes in recording practice makes comparisons of trends in violence against the person offences difficult. While the latest figures have risen, the volume of violence against the person offences recorded by the police is 8% below that recorded in the year ending March 2005. The rates for violence against the person have dropped from 16 recorded offences per 1,000 population in year ending March 2005 to 14 recorded offences per 1,000 population in the year ending March 2015 (Table 5a).

Homicides are not so prone to changes in recording practice by the police. In the year ending March 2015, the police recorded 534 homicides, 1 more than in the previous year (Table 5a)5. Historically, the number of homicides increased from around 300 per year in the early 1960s to over 800 per year in the early years of this century6, a faster rate of increase than the growth in population. Since then,the number of homicides recorded per year has been on a downward trend, while the population of England and Wales has continued to grow. The rate of homicide has fallen by almost half between the year ending March 2004 and the year ending March 2015, from 17 homicides per million population7 to 9 homicides per million population.

From 1 April 2014 stalking became a specific legal offence following the introduction of the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012. Prior to this it would have been hidden within other offences, largely harassment. In the first year that stalking has been a separate offence category, the police recorded 2,878 offences. This change in the law should be borne in mind when looking at trends in harassment (Appendix table A4). Despite the removal of stalking, the number of harassment offences increased 34% to 81,735 in the year ending March 2015. It is thought that this is largely due to increased reporting and recording of domestic violence offences in general, many of which involve some level of harassment.

There is more detailed information on trends and the circumstances of violence against the person in Focus on: Violent Crime and Sexual Offences, 2013/14.

Table 5a: Police recorded violence against the person - number and rate of offences [1,2,3]

| England and Wales | ||||

| Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | Apr '14 to Mar '15 | |

| Violence against the person offences | 845,673 | 699,011 | 634,623 | 779,027 |

| Homicide4 | 868 | 620 | 533 | 534 |

| Violence against the person - with injury5 | 515,119 | 401,244 | 322,818 | 374,216 |

| Violence against the person - without injury6 | 329,686 | 297,147 | 311,272 | 404,277 |

| Violence against the person rate per 1,000 population | 16 | 13 | 11 | 14 |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics | ||||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police) | ||||

| 3. Appendix table A4 provides detailed footnotes and further years | ||||

| 4. Includes the offences of murder, manslaughter, corporate manslaughter and infanticide | ||||

| 5. Includes attempted murder, intentional destruction of viable unborn child, causing death by dangerous driving/careless driving when under the influence of drink or drugs, more serious wounding or other act endangering life (including grievous bodily harm with and without intent), causing death by aggravated vehicle taking, assault with injury, assault with intent to cause serious harm and less serious wounding offences | ||||

| 6. Includes threat or conspiracy to murder, harassment, other offences against children and assault without injury (formerly common assault where there is no injury) | ||||

Download this table Table 5a: Police recorded violence against the person - number and rate of offences [1,2,3]

.xls (30.2 kB)

Table 5b: Police recorded violence against the person - percentage change [1,2,3]

| England and Wales | |||

| Percentage change | |||

| April 2014 to March 2015 compared with: | |||

| Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | |

| Violence against the person offences | -8 | 11 | 23 |

| Homicide4 | -38 | -14 | 0 |

| Violence against the person - with injury5 | -27 | -7 | 16 |

| Violence against the person - without injury6 | 23 | 36 | 30 |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | |||

| Notes: | |||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics | |||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police) | |||

| 3. Appendix table A4 provides detailed footnotes and further years | |||

| 4. Includes the offences of murder, manslaughter, corporate manslaughter and infanticide | |||

| 5. Includes attempted murder, intentional destruction of viable unborn child, causing death by dangerous driving/careless driving when under the influence of drink or drugs, more serious wounding or other act endangering life (including grievous bodily harm with and without intent), causing death by aggravated vehicle taking, assault with injury, assault with intent to cause serious harm and less serious wounding offences | |||

| 6. Includes threat or conspiracy to murder, harassment, other offences against children and assault without injury (formerly common assault where there is no injury) | |||

Download this table Table 5b: Police recorded violence against the person - percentage change [1,2,3]

.xls (30.2 kB)Neither the CSEW nor police recorded crime are good data sources for some “high harm” crimes, where there has been recent increased focus, such as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and modern slavery.

Offences of FGM that come to the attention of the police will be contained within the police recorded crime category of assault with injury. However, it is known that much FGM remains hidden and unreported to the police. The Health and Social Care Information Center (HSCIC) have published new experimental statistics on Female Genital Mutilation8. These data are collected monthly from hospitals in England and are being collected to gain a better picture of the prevalence of FGM9. For the period September to March 2015, there were 3,963 newly identified10 cases of FGM reported nationally. Of course, these are only cases that have come to light as a result of a victim receiving medical treatment and will understate the true volume of such offences.

Modern slavery is currently recorded within a number of police recorded classifications including “sexual offences” and “other crimes against society”. As a result it is not currently possible to identify the number of modern slavery offences coming to the attention of the police. As of 1 April 2015 a separately identifiable offence of modern slavery will be included in the police recorded crime category “violence without injury”. It has been estimated that in 2013 the number of victims of modern slavery ranged between 10,000 and 13,00011.

Notes for violent crime

There is more information on violent crime in Focus on: Violent Crime and Sexual Offences, 2013/14

Based on the latest National Health Service (NHS) Hospital Episode Statistics and hospital admissions due to assault (dated 15 July 2014). These don’t include figures for Wales and relate to activity in English NHS hospitals

The exception was Leicestershire Police, which reported no change

The inspections took place over the period December 2013 to August 2014, this falls within the time period covered by this release. The current year covers the period January 2014 to December 2014 and the comparator year covers the period January 2013 to December 2013

Homicide includes the offences of murder, manslaughter, corporate manslaughter and infanticide

These figures, taken from the Homicide Index, are less likely to be affected by changes to in police recording practice made in 1998 and 2002, so it is possible to examine longer-term trends

While most rates of recorded crime are given per 1,000 population, due to the relatively low number of offences recorded, and to aid interpretation, homicide rates are given per million population

Figures from the Health and Social Care Information Center on Female Genital Mutilation do not include figures for Wales and relate to activity in English foundation and non-foundation trusts including A&E departments. 131 of the 157 eligible acute trusts in England submitted signed off data

Clinical staff must record in patient healthcare records when it is identified that a patient has undergone FGM. This applies to all NHS clinicians and healthcare professionals across the NHS. However, the requirement to submit the FGM Prevalence Dataset is only mandatory for Foundation and non-Foundation trusts, including Accident and Emergency departments. Other organisations (which may include GPs) may wish to provide an FGM Prevalence Dataset centrally, the Data Quality Note contains further information

Patients first identified during the reporting period as having undergone FGM at any stage in their life

This exploratory analysis uses Multiple Systems Estimation (MSE) which includes data on the number of victims of modern slavery from a number of organisaions such as; Local Authorities, Police Forces, Government Organisations (mostly Home Office agencies), Non-governmantal organisations, the National Crime Agency and the General Public (through various routes). The report ‘Modern Slavery: an application of Multiple Systems Estimation’ has more information

6. Robbery

Robbery is an offence in which force, or the threat of force, is used either during or immediately prior to a theft or attempted theft.

Robbery is a relatively low volume offence, accounting for just over 1% of all police recorded crime in the year ending March 2015. The latest figures show police recorded robberies decreased by 13% in the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year (Tables 6a and 6b). With the exception of a notable rise in the number of robberies in 2005/06 and 2006/07, there has been a general downward trend since 2002/03 in England and Wales. The latest figure shows the number of robbery offences falling to 50,236 - the lowest level since the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in 2002/03 (Figure 4).

The Crime-recording: making the victim count report, published by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) found that nationally, an estimated 19% of all offences that should have been recorded as a crime were not. This compares to 14% for robbery offences.

Not all robberies will be reported to the police1, the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) estimated there were 90,000 robbery offences in the year ending March 2015. However, it should be noted that owing to the small number of robbery victims interviewed, CSEW estimates have large confidence intervals and are prone to fluctuation. The number of robberies recorded by the police provides a more robust indication of trends.

Figure 4: Trends in police recorded robberies in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015 [1,2]

England and Wales

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

Notes:

- Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics

- The data on this chart refer to crimes recorded in the financial year (April to March)

Download this chart Figure 4: Trends in police recorded robberies in England and Wales, year ending March 2003 to year ending March 2015 [1,2]

Image .csv .xlsIn the year ending March 2015, 89% of robberies recorded by the police were of personal property. There were 44,482 of these offences, down 15% compared with the previous year. Robbery of business property (which makes up the remaining 11% of total robbery offences) showed similar levels in the year ending March 2015 to those recorded in the previous year. In the year ending March 2015, 1 in 5 robberies (20%) recorded by the police involved a knife or other sharp instrument, a similar level to that recorded in the previous year (Table 9b).

Table 6a: Police recorded robbery - number and rate of offences [1,2,3]

| England and Wales | ||||

| Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | Apr '14 to Mar '15 | |

| Robbery offences | 91,010 | 75,105 | 57,828 | 50,236 |

| Robbery of business property | 7,934 | 8,182 | 5,789 | 5,754 |

| Robbery of personal property | 83,076 | 66,923 | 52,039 | 44,482 |

| Robbery rate per 1,000 population | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | ||||

| Notes: | ||||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics | ||||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police) | ||||

| 3. Appendix table A4 provides detailed footnotes and further years | ||||

Download this table Table 6a: Police recorded robbery - number and rate of offences [1,2,3]

.xls (90.6 kB)

Table 6b: Police recorded robbery - percentage change [1,2,3]

| England and Wales | |||

| Percentage change | |||

| April 2014 to March 2015 compared with: | |||

| Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | |

| Robbery offences | -45 | -33 | -13 |

| Robbery of business property | -27 | -30 | -1 |

| Robbery of personal property | -46 | -34 | -15 |

| Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office | |||

| Notes: | |||

| 1. Police recorded crime data are not designated as National Statistics | |||

| 2. Police recorded crime statistics based on data from all 44 forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police) | |||

| 3. Appendix table A4 provides detailed footnotes and further years | |||

Download this table Table 6b: Police recorded robbery - percentage change [1,2,3]

.xls (90.6 kB)These offences are concentrated in a small number of metropolitan forces with nearly half (44%) of all offences recorded in London, and a further 20% in the Greater Manchester, West Midlands and West Yorkshire police force areas combined (Table P1). The geographic concentration of robbery offences means that trends across England and Wales tend to reflect what is happening in these areas, in particular the Metropolitan Police force area. The latest figures for the Metropolitan Police force area show that the number of robberies for the year ending March 2015 was 21,907, a decrease of 22% from the previous year (Tables P1-P2). This continues the downward trend that began in the year ending March 2013, following a period of increases between 2009 and 2012. The fall in the number of robbery offences in the Metropolitan police force area in the year ending March 2015 accounts for 84% of the total fall in robbery in England and Wales. The Greater Manchester and West Midlands forces account for a further 11%.

The small number of robbery victims interviewed in any single year means that CSEW estimates are prone to fluctuation. However, the CSEW estimate of 90,000 robbery offences in the year ending March 2015 is a decrease (46%) from the 166,000 offences estimated for the previous year and follows several years of falling estimates. The current estimate is 74% lower than the level seen in the 1995 when crime peaked on the survey (Tables 7a and 7b).

Table 7a: CSEW robbery - number, rate and percentage of incidents [1,2]

| England and Wales | |||||

| Adults aged 16 and over | |||||

| Interviews from: | |||||

| Jan '95 to Dec '95 | Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '143 | Apr '14 to Mar '153 | |

| Thousands | |||||

| Number of robbery incidents | 339 | 247 | 320 | 166 | 90 |

| Robbery incidence rate per 1,000 adults | 8 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| Percentage | |||||

| Percentage of adults that were victims of robbery once or more | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Unweighted base - number of adults | 16,337 | 45,118 | 44,559 | 35,371 | 33,350 |

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Appendix table A1, A2, A3 provide detailed footnotes and data for further years | |||||

| 2. Figures are based on analysis of a small number of victims and should be interpreted with caution | |||||

| 3. Base sizes for data since the years ending March 2014 and March 2015 are smaller than previous years, due to sample size reductions introduced in April 2012 | |||||

Download this table Table 7a: CSEW robbery - number, rate and percentage of incidents [1,2]

.xls (30.2 kB)

Table 7b: CSEW robbery - percentage change and statistical significance [1,2]

| England and Wales | ||||||||

| Adults aged 16 and over | ||||||||

| April 2014 to March 2015 compared with: | ||||||||

| Jan '95 to Dec '95 | Apr '04 to Mar '05 | Apr '09 to Mar '10 | Apr '13 to Mar '14 | |||||

| Percentage change and significance3 | ||||||||

| Number of robbery incidents | -74 | * | -64 | * | -72 | * | -46 | * |

| Robbery incidence rate per 1,000 adults | -76 | * | -67 | * | -73 | * | -46 | * |

| Percentage point change and significance3,4 | ||||||||

| Percentage of adults that were victims of robbery once or more | -0.5 | * | -0.3 | * | -0.4 | * | -0.1 | * |

| Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales, Office for National Statistics | ||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||

| 1. Appendix table A1, A2, A3 provide detailed footnotes and data for further years | ||||||||

| 2. Figures are based on analysis of a small number of victims and should be interpreted with caution | ||||||||

| 3. Statistically significant change at the 5% level is indicated by an asterisk | ||||||||

| 4. The percentage point change presented in the tables may differ from subtraction of the 2 percentages due to rounding | ||||||||

Download this table Table 7b: CSEW robbery - percentage change and statistical significance [1,2]

.xls (30.2 kB)Notes for robbery

In the 2014/15 survey, analysis showed that 51% of CSEW robbery offences were reported to the police. Further information can be found in Table D8 in Annual trend and demographic tables, 2014/15 (381.5 Kb Excel sheet).

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Sexual offences

It is difficult to obtain reliable information on the volume of sexual offences as it is known that reporting rates for these type of offences are relatively low compared with other types of offence1. Although the changes in police recorded crime figures may indicate an increased willingness of victims to report sexual offences, they may also reflect changes in recording rather than actual victimisation. For these reasons, caution should be used when interpreting trends in these offences.

Police recorded crime figures showed an increase of 37% in all sexual offences for the year ending March 2015 compared with the previous year (up from 64,229 to 88,219; Table 8a). This is the highest level recorded, and the largest annual percentage increase, since the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in April 2002. Increases in offences against both adults and children have contributed to this rise. Increases were seen in all police forces; Table P2 (296.5 Kb Excel sheet) .

The rises in the volume of sexual offences recorded by the police should be seen in the context of a number of high-profile reports and inquiries which is thought to have resulted in police forces reviewing and improving their recording processes. These include:

the investigation by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) and HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate (HMCPSI)2 in 2012, which highlighted the need to improve the recording and investigation of sexual offences

concerns about the recording of sexual offences, for example in evidence presented to the Public Administration Select Committee (PASC) inquiry into crime statistics3 and arising from other high profile cases