Cynnwys

- Main points

- Things you need to know about this release

- Labour productivity down for second consecutive quarter

- Output per hour up in services but down in manufacturing

- Unit labour costs grow for the ninth consecutive quarter

- Links to related statistics

- What’s changed in this release?

- Quality and methodology

1. Main points

UK labour productivity, as measured by output per hour, is estimated to have fallen by 0.1% from Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2017 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017; over a longer time-period, labour productivity growth has been lower on average than prior to the economic downturn.

Labour productivity grew in services but fell in the manufacturing industries; services productivity grew by 0.2% on the previous quarter, while manufacturing productivity fell by 1.3%.

Earnings and other labour costs growth outpaced productivity growth, resulting in unit labour cost (ULC) growth of 2.4% in the year to Quarter 2 2017.

2. Things you need to know about this release

This release reports labour productivity estimates for Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017 for the whole economy and a range of industries, together with estimates of unit labour costs. Productivity is important as it is considered to be a driver of long-run changes in average living standards.

This edition forms part of our quarterly productivity bulletin, which also includes an overarching commentary, quarterly estimates of public service productivity, and articles on productivity-related topics and data.

Labour productivity is calculated by dividing output by labour input. Output refers to gross value added (GVA), which is an estimate of the volume of goods and services produced by an industry, and in aggregate for the UK as a whole. Labour inputs in this release are measured in terms of workers, jobs (“productivity jobs”) and hours worked (“productivity hours”).

Alongside this release, we have published experimental estimates of current price labour productivity at a more detailed level for the first time.

This release also reports estimates of unit labour costs (ULCs), which capture the full labour costs – including social security and employers’ pension contributions – incurred in the production of a unit of economic output. Labour costs make up around two-thirds of the overall cost of production of UK economic output. Changes in labour costs are therefore a large factor in overall changes in the cost of production. If increases in labour costs are not reflected in the volume of output, this can put upwards pressure on the prices of goods and services – sometimes referred to as “inflationary pressure”. ULCs are therefore a closely watched indicator of inflationary pressure in the economy.

The equations for labour productivity and ULCs can be found in the “Quality and methodology” section of this release.

The output statistics in this release are consistent with the latest Quarterly National Accounts published on 29 September 2017. Note that productivity in this release does not refer to gross domestic product (GDP) per person, which is a measure that includes people who are not in employment.

The labour input measures used in this release are consistent with the latest labour market statistics as described further in the “Quality and methodology” section of this bulletin. Data in this release reflect revisions to GVA and income data incorporated in the latest Quarterly National Accounts.

Unless otherwise stated all figures are seasonally adjusted.

The next labour productivity bulletin (released 5 January 2018) will include a number of small methodological changes previously consulted upon and agreed at a user group held earlier this year. More information on these will be included alongside the next bulletin.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Labour productivity down for second consecutive quarter

Labour productivity on an output per hour basis – our headline measure – fell by 0.1% in Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017. This fall left productivity for Quarter 2 2017 slightly below the peak achieved in Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2007 immediately prior to the economic downturn. Productivity for Quarter 2 2017 was 0.6% below the post-downturn peak that occurred in Quarter 4 2016.

A fall of 0.1% contrasts with a long period of average productivity growth prior to the economic downturn, and represents a continuation of the UK's “productivity puzzle”. This term refers to the relative stagnation of labour productivity since the recent economic downturn. This is in contrast with patterns following previous UK economic downturns where productivity initially fell, but subsequently bounced back to the previous trend rate of growth. There is wide and varied economic debate regarding the causes of this puzzle and further analysis of recent UK productivity trends can be found in the January 2016, May 2016 and June 2016 Economic Reviews, as well as in several standalone articles including: What is the productivity puzzle?, The productivity conundrum, explanations and preliminary analysis, and The productivity conundrum, interpreting the recent behaviour of the economy.

This puzzle is shown in Figure 1, which presents two alternative measures of productivity – output per hour and output per worker – alongside their projected 1994 to 2007 trends. Following years of steady growth, each measure peaked in Quarter 4 2007 and fell during the economic downturn. However, due to a strong labour market performance accompanying a relatively weak recovery in output growth, productivity has not returned to its pre-downturn trend. Productivity in Quarter 2 2017, as measured by output per hour, was 17.2% below its pre-downturn trend – or, equivalently, productivity would have been 20.8% higher had it followed this pre-downturn trend1.

Figure 1: Output per hour and output per worker, UK

Seasonally adjusted, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 1994 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1: Output per hour and output per worker, UK

Image .csv .xlsFigure 2 breaks down the growth in productivity between Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 and Quarter 2 2017 into contributions from different industry groupings and an “allocation effect” due to changes in the share of output and labour in each grouping. All else being equal, stronger (weaker) productivity growth in any given industry, or a movement of output and labour towards (away from) higher productivity industries will tend to raise (reduce) aggregate productivity growth.

Non-financial services are the main positive contributor to productivity growth over this period, partly offset by negative contributions from non-manufacturing production and finance. The negative allocation effect – suggesting that output and labour have been moving away from higher to lower productivity industries in recent years – partly captures the falling share of output in mining and quarrying, which has among the highest levels of productivity of UK industry; partially a result of the falling reserves of oil and gas in the North Sea. Although negative for the period as a whole, the allocation effect was initially positive following the downturn, but turned negative in recent years.

Figure 2: Contributions to growth of whole economy output per hour

Seasonally adjusted, cumulative quarterly changes, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Non-manufacturing production refers to: agriculture, forestry and fishing; mining and quarrying; electricity, gas, steam and air-conditioning supply; and water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities.

Download this chart Figure 2: Contributions to growth of whole economy output per hour

Image .csv .xlsNotes for: Labour productivity down for second consecutive quarter

- Differences between these two measures are due to differences in the denominator used in the calculation. Using the actual output per hour series as the denominator, rather than the trend series, results in a higher percentage gap. This is due to the actual series being lower than the trend series post-downturn.

4. Output per hour up in services but down in manufacturing

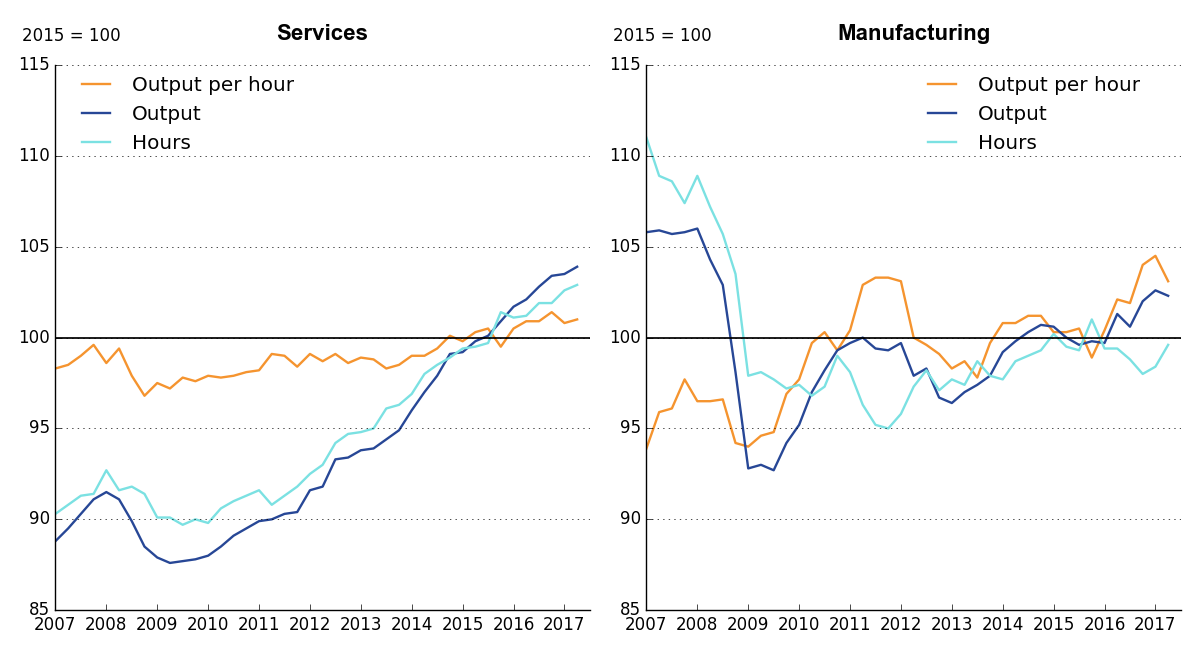

Services output per hour grew by 0.2% in Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017, with output growth outpacing growth in hours worked. In contrast, manufacturing output fell while hours grew so labour productivity in manufacturing declined by 1.3% during the quarter.

Figure 3 examines longer-term trends, showing output per hour and its components since Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008. Services are represented in the left-hand side panel, while manufacturing is represented in the right-hand side panel. Manufacturing output per hour has been more volatile than services in recent years. This reflects a degree of divergence in manufacturing between gross value added (GVA) and hours, most noticeable in 2009 and 2011 to 2012, whereas in services GVA and hours follow fairly similar trends.

Figure 3: Components of services and manufacturing productivity measures

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2007 to Quarter 2 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 3: Components of services and manufacturing productivity measures

.png (87.3 kB) .xls (22.5 kB)5. Unit labour costs grow for the ninth consecutive quarter

Unit labour costs (ULCs) reflect the full labour costs, including social security and employers’ pension contributions, incurred in the production of a unit of economic output. Changes in labour costs are a large factor in overall changes in the cost of production. If increased costs are not reflected in increased output, for instance, this can put upward pressure on the prices of goods and services – sometimes referred to as “inflationary pressure”. ULCs grew by 2.4% in the year to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017, reflecting a larger percentage increase in labour costs per hour than output per hour.

Figure 4 shows changes in ULCs since Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 on a quarter on same quarter a year earlier basis. The bars represent the contribution to changes in ULCs from changes in labour costs per hour and changes in output per hour. Holding other factors constant, increasing output per hour reduces ULCs – as total labour costs remain constant while output rises. As a result, output per hour has its sign reversed in Figure 4. In this presentation, positive (negative) output per hour growth has a negative (positive) effect on ULC growth.

While growth in ULCs has been broadly positive since the onset of the economic downturn, averaging around 1.5% since Quarter 1 2008, there has been substantial variation during this period. During the recent economic downturn, ULCs began to grow at a relative high rate, reaching a peak of 6% by the end of the downturn in Quarter 2 2009 and remaining elevated until Quarter 1 2010. Figure 4 shows that the initial increase in ULC growth during the downturn was driven by falling output per hour, but from Quarter 2 2009 onwards, increasing labour costs per hour were the driving factor. Following the downturn, growth in ULCs began to slow, eventually becoming negative in Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2010.

Following a period of low or negative growth, ULC growth has grown by between 2% and 4% over the past year. This increase broadly reflects higher hourly labour cost growth, with little offsetting output per hour growth.

Figure 4: Whole economy unit labour costs and their compositions, growth on quarter a year ago

Seasonally adjusted, UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2008 to Quarter 2 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Labour costs per hour estimates will differ from those in our Index of Labour Costs per Hour bulletin, due to differences in methodology.

Download this chart Figure 4: Whole economy unit labour costs and their compositions, growth on quarter a year ago

Image .csv .xls7. What’s changed in this release?

This release reflects revisions to gross value added and income data resulting from quarterly national accounts, affecting all time periods. Revisions to the Short-Term Employment Survey affect hours and jobs in Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2017. Revisions to seasonal adjustment affect all periods.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Quality and methodology

The measure of output used in these statistics is the chain volume (real) measure of gross value added (GVA) at basic prices, with the exception of the regional analysis in Table 9, where the output measure is nominal GVA (NGVA). These measures differ because NGVA is not adjusted to account for price changes; this means that if prices were to rise more quickly in one region than the others, then the measures of productivity for that region could show relative growth in productivity compared to other regions purely as a result of the price changes.

Labour input measures used in this bulletin are known as “productivity jobs” and “productivity hours”. Productivity jobs differ from the workforce jobs (WFJ) estimates, published in Table 6 of our labour market statistical bulletin, in three ways:

to achieve consistency with the measurement of GVA, the employee component of productivity jobs is derived on a reporting unit (RU) basis, whereas the employee component of the WFJ estimates is on a local unit (LU) basis

productivity jobs are scaled so industries sum to total Labour Force Survey (LFS) jobs – note that this constraint is applied in non-seasonally adjusted terms; the nature of the seasonal adjustment process means that the sum of seasonally adjusted productivity jobs and hours by industry can differ slightly from the seasonally adjusted LFS totals

productivity jobs are calendar quarter average estimates, whereas WFJ estimates are provided for the last month of each quarter

Productivity hours are derived by multiplying employee and self-employed jobs at an industry level (before seasonal adjustment) by average actual hours worked from the LFS at an industry level. Results are scaled so industries sum to total unadjusted LFS hours, and then seasonally adjusted. Labour productivity is then derived using growth rates for GVA and labour inputs in line with the following equation:

Industry estimates of average hours derived in this process differ from published estimates (found in Table HOUR03 in the labour market statistics release), as the HOUR03 estimates are calculated by allocating all hours worked to the industry of main employment, whereas the productivity hours system takes account of hours worked in first and second jobs by industry.

Whole-economy unit labour costs (ULCs) are calculated as the ratio of total labour costs (that is, the product of labour input and costs per unit of labour) to GVA. Further detail on the methodology can be found in Revised methodology for unit wage costs and unit labour costs: explanation and impact.

The equation for growth of ULCs can be calculated as follows:

Manufacturing unit wage costs are calculated as the ratio of manufacturing average weekly earnings to manufacturing output per filled job. On 28 November 2012 we published Productivity measures: sectional unit labour costs, describing new measures of ULCs below the whole-economy level, and proposing to replace the currently published series for manufacturing unit wage costs with a broader and more consistent measure of ULCs.

A research note, Sources of revisions to labour productivity estimates, is available.

The Labour Productivity Quality and Methodology Information report contains important information on:

- the strengths and limitations of the data and how it compares with related data

- uses and users of the data

- how the output was created

- the quality of the output including accuracy of the data