Cynnwys

- Main points

- Things you need to know about this release

- What is the balance of payments and international investment position?

- Current account deficit widens as total trade deficit deteriorates

- UK total trade deficit drives widening of current account in 2018

- Explore UK trade country data for 2018 with our interactive tools

- Primary income deficit widens slightly in 2018 following a significant recovery in 2017

- How FDI has impacted on the current account

- Investment geography analysis – where do we invest?

- How do we finance our current account deficit?

- UK international investment position net liability widens because of investment flows into the UK by foreign investors and sterling appreciation

1. Main points

- The UK current account deficit widened to 4.3% of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018, from a deficit of 3.5% of GDP in 2017, and remains high by historical standards.

- This was driven mostly by the widening in the trade deficit from 1.2% to 1.8% of GDP in 2018 – the largest trade deficit since 2010; in addition, there was a slight widening to the deficits on both primary income and secondary income, which reached 1.3% and 1.2% respectively.

- The UK financial account recorded a net inflow of £77.2 billion in 2018, equivalent to 8.3% of GDP, as foreign residents invested £177.7 billion in the UK offset partially by UK residents investing £100.6 billion overseas.

- The net international investment position (IIP) widened slightly to £224.2 billion at the end of 2018, equivalent to 10.5% of nominal GDP.

2. Things you need to know about this release

There have been a number of changes and improvements implemented at the start of 2018, which has led to a number of revisions between 1997 and 2017. For more information on these changes please see our earlier article released on 30 August 2019.

Introduced in this Pink Book is a new method for compiling the geographic breakdown of the international investment position. The updated method uses new source data to ensure the most appropriate functional categories breakdown and, for the first time, includes reserve assets in the geographic data, in line with international manuals. Currently, source data are only available for 2018 but we aim to produce a consistent time series for Pink Book 2020.

For more detail on the methodology of the balance of payments please see our Quality and Methodology Information report.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. What is the balance of payments and international investment position?

The balance of payments summarises transactions between residents of a country and non-residents during a period. The Pink Book summarises the economic transactions of the UK with the rest of the world over time. It can be broken into three components: the current account, the capital account and the financial account.

The current account shows the flows of goods and services that comprise international trade, the cross-border income flows associated with the international ownership of financial assets, and current transfers between residents and non-residents. The sum of the balances on these accounts is known as the current account balance.

The capital account consists of capital transfers and the acquisition or disposal of non-produced, non-financial assets.

The sum of the current account balance and capital account balance indicates whether the economy is a net lender to the rest of the world (in surplus) or a net borrower from the rest of the world (in deficit).

The financial account shows the net acquisition or net incurrence of financial assets and liabilities, and is the counterpart to the current account and capital account. It records how the country is financing its borrowing from, or lending to, the rest of the world.

The international investment position (IIP) records the stock position of these financial investments. It shows at the end of the period the value of the stock of financial assets of residents of an economy that are claims on non-residents and the value of the stock of financial liabilities of residents of an economy to non-residents. The difference between the assets and liabilities in the IIP represents either a net claim on, or a net liability to, the rest of the world.

This bulletin gives an analytical overview of the main components of the current account, focusing on the components of primary income and trade. There is also geography analysis looking at the rate of return on investments in different continents. We also have an additional geography map, which showcases the published international investment position map with the UK’s largest trading partners. There is analysis on the financial account and how the UK has financed its current account deficit before and after the economic downturn. Finally, there is analysis on the IIP, which breaks down the elements that make up the IIP.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Current account deficit widens as total trade deficit deteriorates

To assess recent developments in the UK’s external position, Figure 1 breaks down the current account balance into the constituent parts – trade balance, primary income balance and secondary income balance, as a percentage of nominal gross domestic product (GDP). The UK’s current account has been in deficit since 1984, reaching a record level in 2016 of 5.2% of GDP. While the deficit narrowed in 2017 to 3.5%, a deterioration in the trade deficit has led to the current account deficit widening again in 2018 to 4.3%.

The trade deficit widened to 1.8% of GDP (£37.7 billion, a record in cash terms). For further analysis on trade, please see Section 5, UK total trade deficit drives widening of current account in 2018. There was also a slight widening to the deficits on both the primary income balance and secondary income balance to 1.3% and 1.2% respectively in 2018.

Figure 1: UK current account deficit widens to 4.3% of nominal gross domestic product in 2018

Contributions to the change in the UK current account balance as a percentage of GDP, 1984 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 1: UK current account deficit widens to 4.3% of nominal gross domestic product in 2018

Image .csv .xlsOver the long-term we can see that the current account deficit has been influenced mostly by the movements in the trade balance and primary income balance, particularly when it has switched between a surplus and deficit.

The UK’s current account deficit has widened in recent years. The UK recorded the largest deficit in 2018 among other G7 economies at 4.3% of GDP. The UK, Canada and United States are the largest current account deficit holders amongst other advanced economies. In contrast, Germany holds the largest current account surplus at 7.3% of GDP, which is followed by Japan at 3.5% (Figure 2). All advanced economies saw a deterioration on their current account balance as a share of GDP in comparison with 2017.

Figure 2: UK holds the largest current account deficit amongst other advanced economies

Current account balances of the G7 economies 2018, as percentage of GDP

Source: Office for National Statistics, International Monetary Fund

Download this chart Figure 2: UK holds the largest current account deficit amongst other advanced economies

Image .csv .xls5. UK total trade deficit drives widening of current account in 2018

In 2018, the global economy experienced several headwinds. The Bank of England highlights some of these challenges, including: a broad-based slowdown in global economic growth; the imposition of tariff-barriers between two of the biggest economies (United States and China) impacting negatively on global business confidence; while, closer to home, political uncertainties remained.

What impact did all this have on our latest estimates of the UK’s trade balance in 2018, as published in this Pink Book?

The UK trade deficit widened to 1.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018, from 1.2% in 2017, its highest since 2010. As Figure 3 shows, this was due mainly to the UK’s trade surplus with non-European Union (non-EU) countries narrowing to 1.3% of GDP (from 1.9% in 2017) – its narrowest since 2012. The UK’s trade deficit with EU countries remained unchanged in 2018 at 3.1% of GDP.

Figure 3: UK’s trade surplus with non-EU countries in 2018 at its narrowest since 2012

Trade balances as a percentage of nominal gross domestic product, UK, geographic breakdown, 1999 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 3: UK’s trade surplus with non-EU countries in 2018 at its narrowest since 2012

Image .csv .xlsIn nominal terms, the total trade deficit (including goods and services) widened by £12.6 billion to £37.7 billion in 2018. Of that £12.6 billion widening, £10.7 billion was because of the narrowing of the trade surplus with non-EU countries, of which £5.3 billion was because of the widening of the trade deficit with European countries not in the EU (Other Europe), as Figure 4 shows.

As a percentage of GDP, the UK’s trade deficit with European countries not in the EU in 2018 was 0.6% of GDP, its widest since 2012 (when it was 0.9%). The main driver was trade with Russia, in which there was a widening in the trade deficit from £0.8 billion in 2017 to £3.9 billion in 2018. This was due mainly to the value of fuel imports from Russia rising, in line with rising oil prices throughout 2018.

Figure 4: A widening of the trade deficit with European countries not in the EU was the main contributor to the widening UK trade deficit in 2018

Contributions to the change in the UK total trade balance in 2018, geographic breakdown

Source: Office for National Statistics - Balance of payments

Download this chart Figure 4: A widening of the trade deficit with European countries not in the EU was the main contributor to the widening UK trade deficit in 2018

Image .csv .xlsAnother way to look at the overall trade balance is to determine the type of trade driving the deficit (that is, goods or services).

As Figure 5 shows, the widening of the total trade deficit in 2018 to 1.8% of GDP was due mainly to a narrowing of the trade in services surplus to 4.9% (from 5.3% in 2017) and a slightly wider trade in goods deficit of 6.7% of GDP (from 6.6% in 2017).

Figure 5: A narrowing trade in services surplus contributed to the widening total trade deficit in 2018

Trade balances as a percentage of nominal gross domestic product, UK, by trade type, 1999 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 5: A narrowing trade in services surplus contributed to the widening total trade deficit in 2018

Image .csv .xlsIn nominal terms, the trade in services surplus narrowed by £6.1 billion to £104.7 billion in 2018, compared with the previous year. As Figure 6 shows, the main contributors to this narrowing were the following types of services:

- transport services (surplus narrowed by £3.2 billion, due mainly to a £1.3 billion increase in spending on air transport services by UK passengers)

- intellectual property (surplus narrowed by £2.1 billion, due mainly to a £1.6 billion contraction on the value of exported distribution services of audio-visual and related products)

- other business services (surplus narrowed by £1.7 billion, due mainly to a £2.4 billion contraction in the exports of other business services between affiliated enterprises)

- travel services (deficit widened by £1.7 billion, due mainly to a £0.8 billion contraction in the export of business travel services)

The main component partly offsetting the narrowing trade in services surplus was a £1.4 billion increase of the insurance and pension services surplus in 2018, due mainly to a £1.1 billion increase in direct insurance exported.

Figure 6: An increase in the amount of transport services imported was the main contributor to the narrowing of the trade in services surplus

Contributions to the annual change in the trade in services balance in 2018, by service type

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 6: An increase in the amount of transport services imported was the main contributor to the narrowing of the trade in services surplus

Image .csv .xlsIn nominal terms, the trade in goods deficit widened by £6.5 billion in 2018, compared with the previous year. As Figure 7 shows, the main contributors to the widening deficit were the following types of goods:

- coal, gas and electricity (deficit widened by £3.2 billion, due mainly to a £2.7 billion increase in the value imported)

- food, beverages and tobacco (deficit widened by £1.1 billion, due mainly to a £0.9 billion increase in the value imported)

- semi-manufactured goods (deficit widened by £1.1 billion, due mainly to a £1.6 billion increase in the value imported)

The only component partly offsetting the widening trade in goods deficit was finished manufactured goods, as the value of ships and aircraft imported fell by £3.6 billion.

Figure 7: An increase in the amount of coal, gas and electricity imported was the main contributor to the widening of the trade in goods deficit

Contributions to the annual change in the trade in goods balance in 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 7: An increase in the amount of coal, gas and electricity imported was the main contributor to the widening of the trade in goods deficit

Image .csv .xlsA third way of looking at the trade balance is to determine which direction of trade is driving the deficit (that is, exports or imports).

Figure 8: UK exports fell by 0.4 percentage points of GDP while the value of UK imports increased by 0.2 percentage points

Trade balances as a percentage of nominal gross domestic product UK, by trade direction, 1999 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 8: UK exports fell by 0.4 percentage points of GDP while the value of UK imports increased by 0.2 percentage points

Image .csv .xlsAs Figure 8 shows, the widening of the trade deficit to 1.8% of GDP in 2018 was because of the value of UK exports falling by 0.4 percentage points and the value of UK imports increasing by 0.2 percentage points.

In nominal terms, the total trade deficit widened by £12.6 billion in 2018, due mainly to the value of imports rising at a faster rate (£25.7 billion) than exports (£13.1 billion).

Figure 9: Imports of oil and transport services were the main contributors to the rising value of total imports in 2018

Breakdown by goods and services of contributors to change in total imports, 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 9: Imports of oil and transport services were the main contributors to the rising value of total imports in 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 10: Imports from EU countries made up almost half of the total rise in UK imports in 2018

Geographic origin of total UK imports, 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 10: Imports from EU countries made up almost half of the total rise in UK imports in 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 11: Exports of oil and financial services were the main contributors to the rising value of total exports in 2018

Breakdown by goods and services of contributors to change in total exports, 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 11: Exports of oil and financial services were the main contributors to the rising value of total exports in 2018

Image .csv .xls

Figure 12: Exports to EU countries made up 77% of the total rise in UK exports in 2018

Geographic destination of total UK exports, 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 12: Exports to EU countries made up 77% of the total rise in UK exports in 2018

Image .csv .xls6. Explore UK trade country data for 2018 with our interactive tools

Explore the 2018 trade in goods data using our interactive tools. Our data break down UK trade in goods with 234 countries by 125 commodities.

Use our map to get a better understanding of what goods the UK traded with a particular country. Select a country by hovering over it or using the drop-down menu.

Embed code

Notes:

For more information about our methods and how we compile these statistics, please see Trade in goods, country-by-commodity experimental data: 2011 to 2016. Users should note that the data published alongside this release are official statistics and no longer experimental.

These data are our best estimate of these bilateral UK trade flows. Users should note that alternative estimates are available, in some cases, through the statistical agencies for bilateral countries or through central databases such as UN Comtrade.

Interactive maps denote country boundaries in accordance with statistical classifications set out within Appendix 4 of the Balance of Payments (BoP) Vademecum (PDF, 1.1MB).

What about trade in a particular commodity? Use our interactive tools to understand UK trade of a particular commodity in 2018.

Select a commodity from the drop-down menu or click through the levels to explore the data.

Embed code

Embed code

Recent developments now mean you can explore our detailed trade in services data with our interactive tool.

Embed code

What about trade in a particular service type? Use our interactive tools to understand UK trade of a particular service type.

Select a service type from the drop-down menu, or click through the levels to explore the data.

Embed code

Embed code

7. Primary income deficit widens slightly in 2018 following a significant recovery in 2017

Primary income includes investment income, compensation of employees and other primary income. In 2018, the deficit on primary income widened slightly as payments to the rest of the world on investment income increased slightly more than the increase in income received by the UK.

Figure 13 shows that the widening of the primary income deficit in 2018 was because of an increase in debits – that is, money paid out by the UK – to 11.3% of gross domestic product (GDP).

Figure 13: The primary income deficit widened slightly to 1.3% of nominal gross domestic product in 2018

UK primary income balance as a percentage of nominal GDP, 1997 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 13: The primary income deficit widened slightly to 1.3% of nominal gross domestic product in 2018

Image .csv .xlsInvestment income can be broken down further by type of investment:

- foreign direct investment (which is an investment into a company in which the investor has at least 10% or more of the ordinary shares or voting stock and therefore has a controlling influence over the company)

- portfolio investment (which is where the investor does not have any controlling influence, holding less than 10% of the equity capital and debt securities such as corporate bonds)

- other investment (mostly made up of deposits and loans)

- reserve assets (which are short-term assets that can be very quickly converted into cash such as holdings of monetary gold and convertible currencies)

Historically, investment income has been the largest component of primary income, with foreign direct investment being the most volatile element. Figure 14 shows the breakdown of the investment income balance from 1997 to 2018.

Figure 14: The total investment income deficit widened slightly to 1.3% of GDP in 2018 from 1.1% in 2017

Breakdown of UK investment income balance, as percentage of nominal GDP, 1997 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 14: The total investment income deficit widened slightly to 1.3% of GDP in 2018 from 1.1% in 2017

Image .csv .xlsThe foreign direct investment income balance narrowed to 0.9% of GDP in 2018 from 1.5% in 2017, as UK foreign-owned businesses became more profitable. Offsetting this partially were the portfolio income deficit narrowing from 2.3% of GDP in 2017 to 2.0% in 2018, due mostly to increased earnings by the UK on foreign debt securities, and the other investment deficit narrowing from 0.4% of GDP in 2017 to 0.3% in 2018.

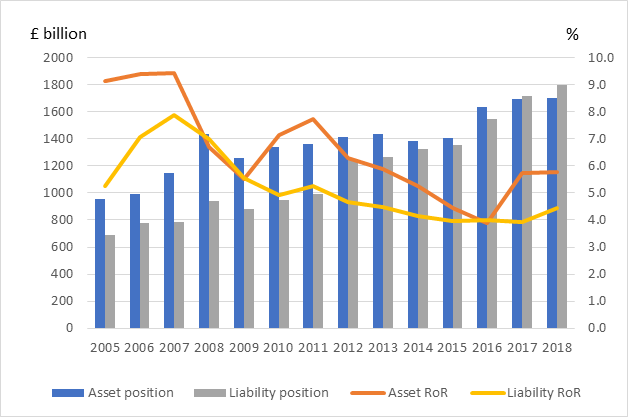

We can also analyse investment performance from the point of view of rates of return. Figure 15 shows that rates of return for both investments in the UK and those abroad continued their recovery in 2018. The rates of return earned on investments in the UK increased from 2.4% in 2017 to 2.6% in 2018, maintaining a better rate of return than that earned on UK investments abroad, which also increased from 2.2% in 2017 to 2.4% in 2018. As such, the net rate of return was unchanged in 2018 and remains negative.

Figure 15: The rates of return earned on investments in the UK increased from 2.4% in 2017 to 2.6% in 2018

Rates of return: UK assets and liabilities¹ , percentage, 1997 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Notes:

- Direct, portfolio and other investments.

- Rates of return are calculated using the average of opening and closing stock positions.

Download this chart Figure 15: The rates of return earned on investments in the UK increased from 2.4% in 2017 to 2.6% in 2018

Image .csv .xls8. How FDI has impacted on the current account

The balance on UK foreign direct investment (FDI) earnings is an important component of the current account, impacting the balance of payments.

FDI earnings can be separated from the other components of primary income in order to assess the influence that FDI has on the current account balance. This is shown in Figure 16, where primary income excludes FDI but includes all other components: earnings from portfolio investment, other investment and reserve assets. The balance on FDI earnings has consistently been in surplus, contributing positively to the current account balance. However, the surplus has narrowed considerably since 2011; falling from a high of £53.5 billion in 2011 to its lowest recorded point of £1.0 billion in 2016.

Figure 16: Foreign direct investment surplus, a main component of the current account, narrowed by £11.1 billion in 2018

UK current account balance and components, 1997 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 16: Foreign direct investment surplus, a main component of the current account, narrowed by £11.1 billion in 2018

Image .csv .xlsThe long-term trend in both UK FDI credits and debits saw the annual earnings of both follow an upward trend from 1997, until the economic downturn in 2008 and 2009. Following the crisis, FDI credits and debits forged different paths (Figure 17). FDI credits rebounded in 2010 and 2011 but then declined to the point of almost converging in 2016 with debits, which had been on a steady upward trend since 2010. The £1.0 billion surplus in 2016 was the narrowest since records began.

The surplus on FDI earnings increased considerably in 2017, increasing by £30.0 billion from 2016. This was a result of FDI credits (earnings on direct investment abroad by UK investors) increasing significantly from £59.0 billion in 2016 to £95.4 billion in 2017. Whereas, FDI debits (earnings on direct investment in the UK by overseas investors) increased to a lesser extent, from £58.0 billion in 2016 to £64.4 billion in 2017.

In 2018, the surplus on FDI earnings narrowed to £19.9 billion from £31.1 billion in 2017 (a fall of £11.1 billion). This was a result of FDI debits increasing more than FDI credits – FDI debits increased by £13.7 billion between 2017 and 2018, whereas credits increased to a lesser extent, by just £2.6 billion.

Figure 17: Surplus on foreign direct investment earnings in 2018 narrowed because the value of FDI debits increased by more than that of credits from 2017

UK FDI credits, debits and balance, 1997 to 2018, £ billion

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 17: Surplus on foreign direct investment earnings in 2018 narrowed because the value of FDI debits increased by more than that of credits from 2017

Image .csv .xlsTwo factors can drive changes in earnings:

- rate of return, for example, interest rates

- level of investment, for example, investing more

Figure 18 shows the UK’s FDI assets and liabilities, and their implied rate of returns, which helps us understand why earnings have changed over time. As seen, the asset levels were relatively unchanged between 2012 and 2015. However, the implied rate of return on UK assets declined over the same period suggesting that earnings were declining because of foreign investments becoming less profitable. The rate of return recovers in 2017 and further still in 2018 to reach 5.8%, making it comparable with that of 2013 (5.9%) suggesting increasing profitability.

This contrasts with the evidence seen for the UK’s FDI liabilities and debits. Despite debits increasing from 2011, Figure 18 shows a declining rate of return, only picking up again in 2018. The explanation for growing debits is the increasing investment by non-residents into the UK as shown by the increasing liabilities. This is confirmed in Figure 22, which shows persistent FDI flows into the UK.

Figure 18: Implied rate of return on UK assets increased slightly in 2018 to 5.6%

UK FDI assets and liabilities (£ billion) and the implied rate of return (%), 2005 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this image Figure 18: Implied rate of return on UK assets increased slightly in 2018 to 5.6%

.png (37.4 kB) .xlsx (26.9 kB)Further analysis of FDI can be found in our UK foreign direct investment: trends and analysis series. The latest edition was published in July 2019, covering the provisional estimate for 2017, the role of exchange rates, and mergers and acquisitions activity in FDI, and experimental statistics from linking FDI microdata with other information.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. Investment geography analysis – where do we invest?

The rate of return that investors receive on their investment is likely to influence investment flows. Usually, investors will be attracted to investments in countries where the rate of return is high, but that is not the only factor that plays into investors’ decision-making. Other factors such as how safe the investment is seen to be also influences the decision. Figures 19 and 20 show the rate of return for UK investments abroad and foreign investments in the UK, broken down by continent.

The rate of return for UK investments abroad increased in every continent in 2018. The highest rate of return for UK investments abroad was in Africa, which increased to 5.2%, while Australasia and Oceania at 4.5% came second in terms of highest return for the UK. The rate of return on UK investments abroad has historically been higher in Africa, whereas in the Americas the UK’s rate of return has been lowest, reflecting how developed the economies are on these continents. Despite enjoying the highest rates of return, the UK, by value, invests the least in Africa.

The rates of return for UK investments in Europe, the Americas and Asia continue to lag since the economic downturn.

Figure 19: Highest rate of return for UK investments abroad came from Africa with an increase of 1.5 percentage points in 2018 to reach 5.2%

Rate of return on UK foreign assets by continent, percentage, 2008 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 19: Highest rate of return for UK investments abroad came from Africa with an increase of 1.5 percentage points in 2018 to reach 5.2%

Image .csv .xlsFigure 20 shows the rate of return on UK liabilities by continent for 2008 to 2018. The rate of return on foreign investments in the UK also increased for each continent in 2018. The largest rate of return was on investment in the UK from Europe at 2.7%. This was closely followed by investment from Asia at 2.6% and the Americas at 2.5%.

Figure 20: Largest rate of return on investments in the UK was on investments held by residents of Europe at 2.7%

Rate of return on UK liabilities by continent, percentage, 2008 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 20: Largest rate of return on investments in the UK was on investments held by residents of Europe at 2.7%

Image .csv .xlsWith the majority of investment flows to and from the UK happening with countries in the European Union (EU), it is interesting to look at these countries in more detail and see how the breakdown of EU investments have changed over recent years.

Use the interactive map to see how investment stocks have changed with different EU countries. Simply hover over the country.

Embed code

10. How do we finance our current account deficit?

Throughout this section when we refer to investments, we use the three main types of investments (direct, portfolio and other) excluding derivatives, employee stock options and reserve assets.

In the run-up to the economic downturn in 2008, the current account deficit was being funded by net investments made into the UK, which were higher than UK net investments abroad. During this time, investments into the UK were made up mainly of other investments: this included more liquid forms of investment such as deposits and loans.

Since the economic downturn, investment flows became more volatile, with some years showing net sales of foreign investments (Figure 21). In recent years, the UK’s current account deficit has returned to being funded by net investment flows into the UK outpacing net investment overseas.

Figure 21: Net inward investment flows to the UK were relatively low in 2018 decreasing from 2017 (23.7% of GDP) to 8.3% of GDP

UK inward and outward financial flows as a percentage of nominal GDP, 1997 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 21: Net inward investment flows to the UK were relatively low in 2018 decreasing from 2017 (23.7% of GDP) to 8.3% of GDP

Image .csv .xlsNet inward investment flows into the UK decreased substantially from 23.7% in 2017 to 8.3% in 2018. This was due mainly to a decrease in other investments from 10.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017 to 0.1% of GDP in 2018.

Figure 22 shows the net inward financial flows as a percentage of nominal GDP, 1997 to 2018. It shows that FDI inflows dropped in 2018 to 1.3%, from 4.6% in 2017. In contrast, investment in UK debt securities increased and was the main investment vehicle used by non-residents in 2018 at a value equivalent to 6.6% of GDP.

Figure 22: Foreign direct investment, which has been a consistent contributing factor to the inflows of investment into the UK, decreased in 2018

UK net inward financial flows as a percentage of nominal GDP, 1997 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 22: Foreign direct investment, which has been a consistent contributing factor to the inflows of investment into the UK, decreased in 2018

Image .csv .xls11. UK international investment position net liability widens because of investment flows into the UK by foreign investors and sterling appreciation

The international investment position (IIP) measures the stock of assets and liabilities at the end of period, and is the sum of the opening balance, financial flows and other changes (including price changes, currency changes and so on).

All else remaining the same, the widening in the current account deficit means the UK is more reliant on incurring net financial liabilities to finance its borrowing from the rest of the world and therefore the net liability would be expected to widen. However, there can also be revaluation effects and other changes in volumes, that do not reflect movements in financial transactions.

The net IIP widened marginally in 2018 to £224.2 billion, from £208.1 billion in 2017 (equivalent to 10.5% and 10.0% of gross domestic product (GDP) respectively, see Figure 23). The widening was because of total liabilities increasing by £201.7 billion to £11,221.4 billion while total assets only increased by £185.7 billion to £10,997.3 billion.

Figure 23: The net IIP marginally widened in 2018 to £224.2 billion equivalent to 10.5% of GDP

UK net IIP as a percentage of nominal gross domestic product, 1997 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 23: The net IIP marginally widened in 2018 to £224.2 billion equivalent to 10.5% of GDP

Image .csv .xlsThroughout this section when we refer to investments, we use the three main types of investments (direct, portfolio and other) excluding financial derivatives and employee stock options and reserve assets. This is because it is possible to estimate the impact of both currency and price changes on the three main types of investments.

Financial flows are one of the main factors driving the change in the UK’s assets and liabilities. The variations in stock not only reflect the accumulation of new assets and liabilities but also the disposal or revaluation of existing ones and changes in the sterling exchange rate. Changes in exchange rates affect the sterling value of UK assets abroad as they are denominated mainly in foreign currencies. Another factor that could impact upon the revaluation of these assets and liabilities is equity price movements, which can impact on the value but not the underlying volume.

Volatile currency changes have been the driving factors behind the changes in the UK’s assets and liabilities since the European Union referendum in 2016. This reflects that a significant proportion of the UK’s external liabilities is denominated in a foreign currency. As such, currency movements impact upon the sterling value of the UK’s IIP.

Figure 24 shows the total annual change in the UK’s IIP assets from 2001 to 2018. It shows that, of the £111.8 billion increase in the value of UK assets in 2018, £68.7 billion was because of new investment. Currency effects had a positive impact of £307.4 billion as sterling depreciated and partially offsetting these, price changes had a negative impact of £130.2 billion. The impact from price changes reflects the fact that global stock markets retreated to close the year at a lower point than at which they opened the year. According to the analysis, this decrease in prices ended six continuous years of increasing values.

Figure 24: An increase of £111.8 billion in the value of UK assets in 2018

Total annual change in annual UK IIP assets broken down into impacts, 2001 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 24: An increase of £111.8 billion in the value of UK assets in 2018

Image .csv .xlsWe can also analyse why the UK’s IIP liabilities increased more than assets over 2018. Likewise with assets, exchange rate movements affect the UK’s liabilities as well. This is because of the UK’s large financial sector with which foreign investors deposit large amounts of foreign currency. Figure 25 shows the total annual changes in the UK’s liabilities by impacts in 2001 to 2018.

Of the £160.3 billion increase in the value of UK liabilities in 2018, £177.7 billion was because of new investment into the UK, currency changes had a positive impact of £203.5 billion and price change had a negative impact of £200.9 billion, reflecting movements in UK equities.

Figure 25: An increase of £160.3 billion in the value of UK liabilities in 2018

Total annual change in annual UK IIP liabilities broken down into impacts, 2001 to 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics – Balance of Payments

Download this chart Figure 25: An increase of £160.3 billion in the value of UK liabilities in 2018

Image .csv .xlsNote: To obtain the exchange rate impact, we have calculated currency changes by calculating sterling exchange rate movements against a basket of currencies. Similarly, price movements are modelled using a combination of stocks and bond indices including end-quarter share prices for the Dow Jones, Euro Stoxx, FT-SE and Nikkei exchanges (for more information see article on the UK’s international investment position, 2016). An update of the analysis on UK’s IIP over the years will be published in the near future.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys