Cynnwys

- Main points

- Introduction

- Current account overview

- Trade

- Primary income

- Examination of the UK’s stock position

- An examination of the rate of return

- Geographic analysis of UK foreign assets

- Geographic analysis of UK liabilities to foreign investors

- Geographic analysis of the UK’s net IIP

- Authors, editor and production team

- Background notes

1. Main points

The deterioration in the current account balance in recent years, leading to a record deficit of 5.4% as a percentage of nominal GDP in 2015, was largely due to UK earnings on assets overseas falling relative to the earnings of foreign investors in the UK.

In 2015, the UK recorded the largest current account deficit as a percentage of GDP among the G7 economies.

UK exports grew faster than world exports in 2015, for the first time since 2006. Within this the UK has seen increased trade activity in goods with non-EU countries, with their share exceeding that of EU countries in the last four years.

The decline in the primary income balance in recent years has been due to both; the stock of assets that the UK holds abroad falling relative to the stock of assets held by foreign investors in the UK; and the rate of return the UK receives on its assets abroad slightly falling while the rate of return earned by foreign investors in the UK slightly rising.

On a functional category basis, the deterioration in the investment income balance has been due to a fall in direct investment earnings and a worsening of earnings on portfolio investment

In recent years, the UK’s external position has deteriorated, showing a net liability position of 14.4% as a percentage of nominal GDP in 2015.

Roughly 45% of the UK’s investment abroad is in Europe, with around 35% of holdings in the Americas. UK liabilities show a similar picture with just over half of investment into the UK coming from Europe, while around 33% coming from the Americas.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Introduction

This section of the Pink Book provides an examination of recent trends, important movements and international comparisons for a range of information contained within the Pink Book. All international data have been sourced from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) on 19 July 2016.

The balance of payments measures the economic transactions of the UK with the rest of the world. These transactions can be broken down into 3 main accounts: the current account, the capital account and the financial account. The current account comprises the trade in goods and services account, the primary income account and secondary income account. The balance on these accounts is known as the current account balance.

To elaborate on the conceptual framework, a current account balance is in surplus if overall credits exceed debits and in deficit if overall debits exceed credits. Closely related to the balance of payments is the international investment position series of statistics. The international investment position measures the levels of financial investment with the rest of the world, inward and outward. Developments in these measures are of substantial importance in assessing the degree of external balance that the UK experiences. For instance, external macroeconomic shocks can be transmitted rapidly to the UK economy through investment choices of both UK and foreign investors, as well as through changes in assets prices and fluctuations in the exchange rate. These shocks could have a wider effect on the whole economy than would be implied through trade and investment links alone.

This commentary gives an analytical overview of the UK’s current account and its constituent parts. It focuses primarily on the trade account and primary income account to assess both their changing roles in the deterioration of the current account balance. There is also a further decomposition of the international investment positions (mainly trends in direct investment) and their subsequent rates of return, to assess their contribution in the decline of primary income in recent years.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Current account overview

To assess recent developments in the UK’s external position, Figure 1 breaks down the current account balance into its constituent parts – the trade balance, the primary income balance (which comprises of investment income, compensation of employees and other primary income), and the secondary income balance that captures transfers between the UK and other countries (for example official payments to and receipts from EU institutions and other international bodies). It shows that the UK has recorded a current account deficit every year since 1995. From 1998 to 2008 the deficit widened, peaking at 3.5% of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) in 2008. In subsequent years, the deficit narrowed slightly but widened thereafter. Latest figures show the current account deficit widening to 5.4% of nominal GDP in 2015, representing the largest deficit (in annual terms) since records began in 1948. This deterioration in performance can be partly attributed to the recent weakness in the primary income balance: due to UK earnings on assets overseas falling relative to the earnings of foreign investors in the UK.

Figure 1: UK current account balance and constituent parts as a percentage of nominal GDP, 1995 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1: UK current account balance and constituent parts as a percentage of nominal GDP, 1995 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsAlthough previous deteriorations in the current account balance have been driven by a fall in the balance on trade, the recent deterioration is a consequence of a sharply lower primary income balance - largely driven by a fall in investment income which accounts for the vast majority of primary income. The primary income balance also reached a record annual deficit in 2015 of 2% of nominal GDP; a figure that is mainly attributed to a fall in UK residents’ earnings from investment abroad, and broadly stable foreign resident earnings on their investments in the UK.

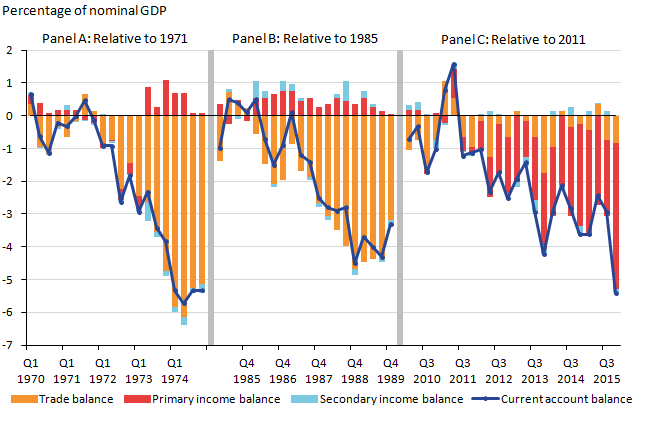

Figure 2 compares contributions to the fall in the current account balance since 2011 (Panel C) to previous occurrences in the 1970s (Panel A) and 1980s (Panel B). The first two panels show that previous declines – of 5.3% and 3.3% of GDP respectively – were mainly driven by the balance of trade. In contrast, the latest decline of the current account of 5.4% of GDP since 2011 has been driven by a decline of the primary income balance.

Figure 2: Contributions to the deterioration in the UK current account relative to selected calendar years, percentage of nominal GDP

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 2: Contributions to the deterioration in the UK current account relative to selected calendar years, percentage of nominal GDP

.png (31.3 kB) .xls (33.3 kB)From an international perspective, there have been striking divergences in the relative performance of current accounts among the major developed economies. Figure 3 compares the current account balance as a proportion of GDP in the G7 economies (USA, Japan, UK, Germany, France, Italy and Canada) for the two most recent calendar years with that in 2007. This highlights how the external position of major economies has evolved following the economic downturn in 2008 and 2009.

Figure 3 shows that 3 of the 7 economies (including the UK) have experienced deteriorating current account balances relative to 2007; however the UK recorded the largest current account deficit among these economies in 2015 at 5.4% of GDP. This also represented a worsening position relative to 2014. In contrast, Germany experienced the largest current account surplus in 2015 (8.5% of GDP). Of the 7 countries, Germany, Italy, France and the USA are the economies that saw an improvement on their current account balance as a share of GDP in 2015 relative to 2007.

Figure 3: Current account balances of the G7 economies, 2007, 2014 and 2015, percentage of nominal GDP

Source: Office for National Statistics and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Notes:

- Data for Japan in 2007 is sourced from the Japanese Cabinet Office.

Download this chart Figure 3: Current account balances of the G7 economies, 2007, 2014 and 2015, percentage of nominal GDP

Image .csv .xls4. Trade

The UK’s trade balance – the difference between exports and imports – has been in deficit (imports higher than exports) since 1998. The UK currently runs a deficit in trade in goods – which is partly offset by a surplus in trade in services. Data for 2015 suggests that the goods deficit widened to 6.9% of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) from 6.7% in 2014, while the surplus in services remained broadly unchanged at 4.7% over the same period.

Figure 4: UK trade in goods and services balance, current prices, 1995 to 2015, percentage of nominal GDP

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: UK trade in goods and services balance, current prices, 1995 to 2015, percentage of nominal GDP

Image .csv .xlsThe value of UK exports of goods to non-EU countries has exceeded goods exports to the EU in the last four years (2012 to 2015). UK goods exports to non-EU countries were valued at £151 billion while goods exports to the EU stood at £134 billion in 2015. Figure 5 shows that UK goods exports to non-EU countries have grown at a faster rate than UK goods exports to the EU, with the former averaging 5.8% each year since 1999. Over the years prior to and during the economic downturn, the share of goods exports accounted for by non-EU countries gradually rose, to the extent that it now accounts for over half of goods exports. The value of goods exports to EU countries fell in 2012 and has been subdued since, falling by 3.4% and 2.7% in 2014 and 2015 respectively. This coincided with the heightened uncertainty in the euro area in 2012, and highlights the relative economic performances of the UK’s trading partners since then, with much weaker demand growth in the EU markets and much stronger demand growth in the non-EU markets. This might suggest that the extent of overseas demand for UK products may have been limited by prevailing global economic conditions.

Figure 5: UK goods exports to the EU and non-EU areas, percentage of total UK goods exports, current prices, 1999 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 5: UK goods exports to the EU and non-EU areas, percentage of total UK goods exports, current prices, 1999 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsThe level of total UK trade in goods as a proportion of total trade in goods and services has been gradually declining since 1986 after peaking at 75% in 1985. This is consistent with the rising share of UK trade in services (44% of total trade in 2015) – indicative of the UK’s relative strength in services activities. UK exports of services to the EU have grown by 7% on average each year since 2000 while exports of services to non-EU countries have grown by 7.3% on average each year over the same period (2000 to 2015).

The rise in the share of services is largely driven by total professional and management consulting services particularly business management and management consulting (these are grouped into the “other business services” category in Figure 6). Total professional and management services now account for 9.5% of UK export services, up by 4.2 percentage points compared to 1999. However, the UK’s strength in services remains driven by financial services which accounted for 22.5% of UK services exports in 2015- which grew by 3.1%. Latest ONS data suggests that the largest positive contribution to services exports growth in 2015 came from other business services which made a 4.4 percentage point contribution, of which 3.4 percentage points was attributed to technical, trade related and other business services. Technical, trade related and other business services accounted for 19.6% of services exports in 2015.

Figure 6: UK trade in services export and import proportions by type, current prices, 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 6: UK trade in services export and import proportions by type, current prices, 2015

Image .csv .xlsFigure 7 shows growth of UK goods and services exports compared with world export growth and weighted world GDP growth. The latter involves weighting the GDP growth in each partner country by their relative share of UK exports. These statistics should be interpreted with care as they aggregate diverse conditions in a large number of different markets. It shows that UK exports growth broadly tracks weighted GDP growth for other countries, with higher demand from abroad broadly translating to higher export growth. UK export growth has dropped below world export growth in most years but was higher in 2015.

Figure 7: Annual change in world export growth, weighted world GDP growth and UK export growth, chained volume measure as percentage, 1995 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics and International Monetary Fund

Download this chart Figure 7: Annual change in world export growth, weighted world GDP growth and UK export growth, chained volume measure as percentage, 1995 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsUK trade in goods and services with the EU involves some bilateral surpluses (Ireland and in some years the Netherlands) and some deficits, as seen in Figure 8. The most substantial bilateral deficit within the EU is with Germany, which increased by 46.6% in 2015 (£25 billion) relative to 2007. The UK trade balance with respect to Germany has been in deficit in the past decade with the largest record seen in 2015. In contrast, the UK’s trade balance with Ireland has been in surplus all through from 1999, while UK trade with the Netherlands has experienced both deficits and surpluses during this period. It is worth noting the impact that the “Rotterdam effect” can have on trade in goods, further details of which can be found in the background notes, section 5, understanding the data. The UK trade deficit with EU countries as a whole is currently valued at £69 billion, a 17.9% deterioration compared with 2014.

Figure 8: UK trade in goods and services balance with the EU and selected EU countries, 1999 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 8: UK trade in goods and services balance with the EU and selected EU countries, 1999 to 2015

Image .csv .xls

Figure 9: UK trade in goods and services balance with selected non-EU countries, 1999 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 9: UK trade in goods and services balance with selected non-EU countries, 1999 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsAmong the non-EU countries, the UK has seen rising surpluses in trade with the USA in recent years, with a level of £39 billion in 2015, slightly below the record level of £40 billion seen in 2013 (Figure 9). The UK however, has experienced a growing trade deficit with China since 1999, although this has broadly stabilised since 2010 - it currently stands at £23 billion.

Figure 10 compares the trade balance as a proportion of GDP in the G7 economies (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, USA and UK) for the calendar year 2015 with that of 2014 and 2007. A number of other G7 economies (Canada, France, Japan and USA) have also recorded persistent trade deficits while Germany and Italy currently achieve a surplus. Figure 10 shows that 4 of the 7 economies (the UK included) experienced an improvement in their trade balance relative to 2007. However the UK and Canada were the only countries that saw a worsening in their trade balance between 2014 and 2015 (-2.1% of GDP for the UK and -2.3% of GDP for Canada).

Figure 10: G7 trade balance, percentage of nominal GDP, 2007, 2014 and 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Bureau for Economic analysis and Cabinet Office

Notes:

- Data for Japan has been sourced from the Cabinet Office.

- Data for the USA has been sourced from the Bureau for Economic analysis.

Download this chart Figure 10: G7 trade balance, percentage of nominal GDP, 2007, 2014 and 2015

Image .csv .xls5. Primary income

Figure 2 showed how the deterioration in the current account balance has become less attributable to the trade balance and more attributable to the decline in the primary income balance. This suggests that UK earnings on assets overseas fell in value relative to the earnings of foreign investors in the UK. Figure 11 shows the main drivers of the primary income balance. This is a net concept, so it factors in the income flows to and from the UK on our assets and liabilities with the rest of the world. It shows that the recent deterioration in the primary income balance can be attributed to the decline in the direct investment income balance and net income earned on debt securities.

Figure 11: Contribution to the UK primary income balance as percentage of nominal GDP, current price, 1997 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- “other” includes: Other primary income, reserve assets and compensation of employees.

Download this chart Figure 11: Contribution to the UK primary income balance as percentage of nominal GDP, current price, 1997 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsThe fall in the balance on primary income reflects a combination of different effects, including a relative fall in the rates of return on UK assets held overseas. As set out in previous analysis, the balance on primary income largely depends on the relative quantities of assets held by UK investors overseas and overseas investors in the UK, and the relative rates of return that they earn on their respective portfolios. All else being equal, larger holdings of UK assets by overseas investors will tend to decrease the balance on primary income. Similarly, a relative rise in the rate of return earned by foreign investors on UK assets will tend to decrease the balance on primary income.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Examination of the UK’s stock position

With UK residents investing in overseas assets at a slower rate compared to their foreign counterparts, there has also been a worsening of the UK’s International Investment Position (IIP). The UK’s IIP comprises of UK assets (UK residents’ holdings of overseas assets), and UK liabilities (foreign owned assets in the UK); with the Net International Investment Position (NIIP) simply being the difference between them. The five functional categories of the NIIP are: direct investment (defined as a lasting interest in an enterprise in another economy, with a large degree of influence and ownership of at least 10% equity), portfolio investment (equity investments representing less than 10% of the equity of an enterprise and debt instruments), financial derivatives (derivatives are dependent on other assets), other investment (investment other than direct and portfolio investment) and reserve assets.

Figure 12 outlines the contribution to the UK’s NIIP during the past two decades. Since 1995, the NIIP has consistently represented a net liability position, with the exception of a brief net asset position in 2008. However, in recent years, the UK’s external position has deteriorated further, with latest estimates showing a net liability position of around 14.4% of nominal GDP in 2015. This broadly represents the accumulated deficits that the UK has accrued with the rest of the world and gives an indication of the degree of external balance that the UK experiences. An article exploring the changes in the IIP between 1999 and 2014 is also available on our website.

Historically, the UK has offset mostly negative net portfolio and other investment with much larger positive net direct investment positions. A larger deficit on portfolio investment and increased overseas holdings of UK foreign direct investment (FDI) assets in the UK combined with lower UK holdings of FDI abroad, account for the majority of the recent fall in the NIIP.

Figure 12: Contribution to UK net international investment position as percentage of nominal GDP, 1995 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Financial derivatives data collected from 2004.

Download this chart Figure 12: Contribution to UK net international investment position as percentage of nominal GDP, 1995 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsFigure 13 focuses on the UK’s FDI position in detail, and shows asset and liability stocks as well as the net figure as a percentage of nominal GDP. Prior to 2012, the UK’s net FDI positions were markedly above zero as UK investors held more overseas assets (UK assets) than overseas investors holdings of UK assets (UK liabilities). The gap between these two positions has converged in subsequent years, with the stocks of UK assets and that of UK liabilities being broadly similar at 74.7% and 74.3% of GDP respectively, recording the lowest FDI net position (0.4% of GDP in 2015) since records began. The UK’s net FDI position reduced from a net asset position of 31.6% in 2008 to a net asset position of only 0.4% of nominal GDP, in 2015.

Figure 13: UK long-run FDI assets, liabilities and net stocks, as percentage of nominal GDP, 1995 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 13: UK long-run FDI assets, liabilities and net stocks, as percentage of nominal GDP, 1995 to 2015

Image .csv .xls7. An examination of the rate of return

While the total value of UK investors’ holdings of overseas assets has fallen relative to the value of holdings in the UK by overseas investors, the fall in the rate of return on UK assets overseas may have also played an important role in the widening of the deficit on the primary income balance (earning on investments). Outlined in the above section, a fall in the rate of return earned by UK investors (overseas investors) will tend to decrease (increase) the balance on investment income. For a detailed look at the developments in these measures, Figure 14 shows the rates of return received by UK and overseas investors for three different forms of asset classes: direct investment, portfolio investment and other investments. More information on rates of return can be found in the background notes, section 5, understanding the data. It shows that prior to 2008, UK residents generated a higher rate of return on their direct and portfolio investments abroad than foreign investors generated on their UK investments.

Figure 14: Rates of return: direct, portfolio and other investments assets and liabilities, percentage, 1997 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 14: Rates of return: direct, portfolio and other investments assets and liabilities, percentage, 1997 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsHowever, in the period coinciding with the further marked deterioration in the primary income balance (2012 to 2015), the rates of return on direct investments have now converged and overseas investors now generate a higher rate of return on direct investments than their UK counterparts. This might reflect a range of factors such as, the relative strength of the UK economy to the overseas economies in which UK assets are based, fluctuations in the exchange rate and the industries in which the UK is invested.

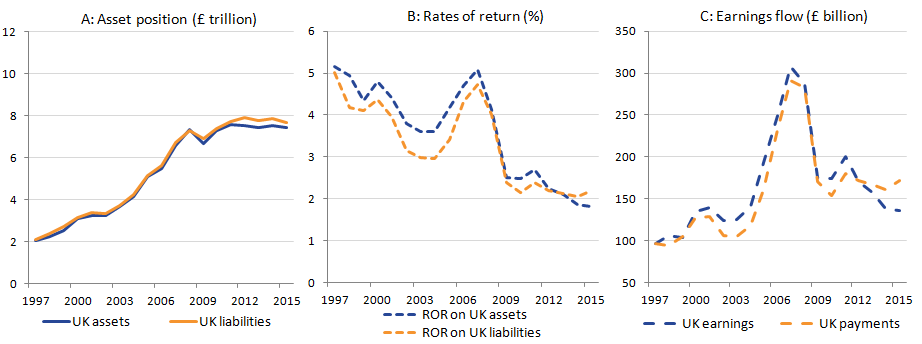

Figure 15 summarises the main factors that appear to be driving the recent decline in the primary income balance. Firstly, the gap between the stock of assets that the UK holds abroad and the stock of assets held by foreign investors in the UK has widened in recent years. This is likely to be the result of a combination of currency effects and relative movements in FDI flows which have had a greater impact on the stock of UK assets held abroad. Secondly, the rate of return that the UK receives on its assets abroad has fallen slightly, while the rate of return earned by foreign investors on assets in the UK has risen slightly. This likely reflects the relative strength of the UK economy, in particular relative to the euro area, where a large fraction of the UK’s overseas assets are based. Both of these factors have driven a growing wedge between UK earnings abroad and foreign earnings in the UK, as shown in Panel C.

Figure 15: Assets (£ trillion), rates of return (%) and earnings (£ billion) for UK assets overseas and overseas assets in the UK, 1997 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 15: Assets (£ trillion), rates of return (%) and earnings (£ billion) for UK assets overseas and overseas assets in the UK, 1997 to 2015

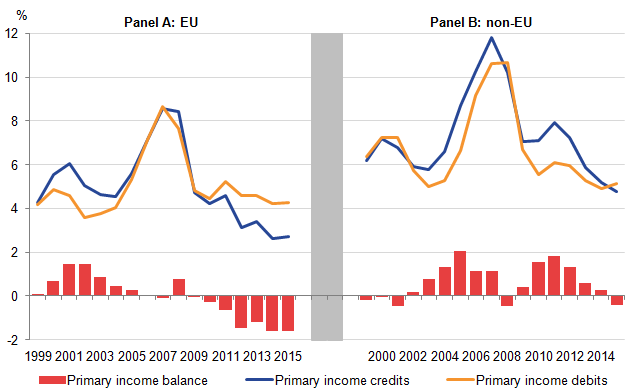

.png (33.6 kB) .xls (30.2 kB)Figure 16 shows the UK’s primary income balance with the EU and non-EU. Credits refer to income earned by UK residents on assets abroad while debits refer to income earned by foreign residents from UK assets. It shows that since 2009 the primary income balance with the EU started to decline, as income received by UK residents on EU assets slowed, while income received by EU residents stayed broadly stable. In 2015, the UK’s net primary income with the EU stood at -1.6% of GDP, unchanged from 2014.

Figure 16: UK primary income balance with the EU and non-EU areas, percentage of nominal GDP, 1999 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 16: UK primary income balance with the EU and non-EU areas, percentage of nominal GDP, 1999 to 2015

.png (24.4 kB) .xls (30.7 kB)The UK’s primary income balance with non-EU countries has also deteriorated in recent years. Between 2011 and 2015, UK residents’ earnings on non-EU assets declined at a faster rate compared to non-EU resident income, while the latest data for 2015 shows that the UK’s primary income balance with non-EU countries is in deficit for the first time since 2008.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Geographic analysis of UK foreign assets

As previously mentioned, the amount of earnings from investments is determined by the amount invested and the associated rate of return. Analysing levels and the rates of return on investments that the UK holds can shed some light on the reasons behind the decrease in earnings the UK is currently experiencing from its investments abroad. This section focuses on direct, portfolio and other investment assets, given that there is no direct income associated with financial derivative investments.

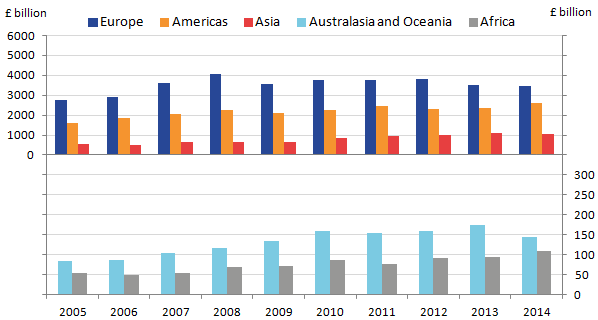

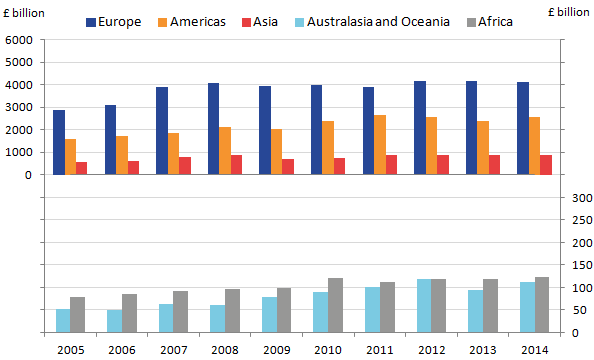

Roughly 45% of the UK’s investment abroad is in Europe with around 35% of holdings in the Americas (Figure 17). The holdings in the Americas are very much dominated by investment in the United States of America which is the single largest country that the UK invests in, fluctuating around 25% of UK asset holdings. Given that UK investments in Asia represent 13% of total UK assets, these 3 continents account for more than 90% of all UK overseas investments. While the majority of UK investments are held in what might be considered the developed markets of Europe, the Americas and Asia, Figure 18, shows that they realise the smallest return on investment.

Figure 17: UK foreign assets by continent, £ billion, 2005 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 17: UK foreign assets by continent, £ billion, 2005 to 2014

.png (9.7 kB) .xls (29.7 kB)Reviewing rates of return on UK assets abroad since 2006, Figure 18 shows how rates of return have not recovered following the global financial crisis of 2008/2009. Only Africa, Australasia and Oceania and to a lesser extent Asia showed some recovery in the years immediately after the crisis, but have since declined to similar rates of return seen from European and American investments. Overall this decline in UK earnings from abroad is due to a levelling off of investment abroad combined with lower rates of return, due to a combination of continued low interest rates and evidence of lower profits from direct investment ventures.

Figure 18: Rate of return on UK foreign assets by continent, percentage, 2006 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 18: Rate of return on UK foreign assets by continent, percentage, 2006 to 2014

Image .csv .xls9. Geographic analysis of UK liabilities to foreign investors

The UK’s liabilities show a similar picture to UK assets abroad with the majority of inward investment coming from Europe (around 52% of total liabilities) and the Americas (around 33%). Again the USA is the largest single counterparty holding around 26% of UK liabilities.

Figure 19: UK liabilities to foreign investors by continent, £ billion, 2005 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 19: UK liabilities to foreign investors by continent, £ billion, 2005 to 2014

.png (15.4 kB) .xls (30.2 kB)Figure 20 displays the rates of return paid to foreign investors in the UK.

Figure 20: Rate of return on UK liabilities by continent, percentage, 2006 to 2014

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 20: Rate of return on UK liabilities by continent, percentage, 2006 to 2014

Image .csv .xlsAs could be expected, foreign investors in the UK receive broadly similar rates of return on their investments. The minor differences are due to an investors' appetite for risk and how they arrange their portfolio of investments between asset classes. The returns earned by European investors are slightly higher due to the amount of their direct investment in the UK which is around half of all direct investment in the UK.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys10. Geographic analysis of the UK’s net IIP

The UK has held a net liability position for some time with the rest of the world. However, the net IIP with individual continents are a mixture of net liability and net asset positions. The UK has consistently held a net liability position with Europe. This liability position has significantly increased in recent years, reaching £679 billion in 2014. The net IIP position with the Americas has fluctuated between a net asset and net liability position throughout the time period, while a net liability position with Asia switched to a net asset position in 2010 and has remained an asset position in recent years. Given the UK has a net liability position with the rest of the world, even with consistent rates of return, the UK would be paying the rest of the world more on their investments held in the UK than it receives from its investments abroad. Given the evidence that in recent years UK rates of return on investments abroad are lower relative to foreign rates of return on investment in the UK, then this further explains why there has been a significant deterioration in the UK’s balance on investment income.