1. Acknowledgements

Authors: Sami Hamroush, Matthew Luff, Andrew Banks, and Michael Hardie.

The authors would like to acknowledge contributions from Chloe Gibbs, Claire Dobbins, Laura Pullin, Rachel Jones, Matthew Dickinson, Aled Jones, and Blue Mansfield.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys2. Main points

The current account deficit continued to widen in 2015, reaching a record high of 5.2% of nominal gross domestic product (GDP).

The increase in the current account deficit in 2015 marks the fourth consecutive annual deterioration since 2011, more than 80% of which is attributable to falls in net foreign direct investment (FDI) earnings.

Falling FDI credits over this period explain just under 80% of the decline in net FDI earnings, with the remainder explained by increases in debits.

There are a number of factors that may be responsible for this recent deterioration – however, it is likely that the performance of multinational companies and commodity prices have played a central role.

The majority of the decline in FDI credits is attributable to the largest 25 multinational companies, while the rise in debits is more diverse.

The contrasting performance in credits and debits partly reflects the fact that UK FDI assets are exposed to movements in global commodity prices – most notably crude oil.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Introduction

The UK current account has remained in deficit for over three decades. The period between 1999 and 2005 saw the deficit narrow from 2.5% to 1.2% of nominal gross domestic product (GDP), before widening in the years leading up to the 2008-09 economic downturn. Despite an improvement immediately following the downturn, the current account deficit has deteriorated from 1.7% of GDP in 2011 to an annual record 5.2% in 2015, according to the latest published estimates (Balance of payments for the UK: Oct to Dec and annual 2015, 31 March 2016).

Whereas the increases in the UK current account deficit during the mid-1970s and late 1980s were largely due to deteriorating trade balances, more recently the decline has been driven by direct investment income; this accounts for more than 80% of the increase in the deficit since 2011. Figure 1 shows that direct investment earnings have declined from a surplus of 3.3% of nominal GDP in 2011 to a deficit of 0.2% in 2015.

The FDI data for 2013 and 2014 presented in this paper make use of the recent FDI publication, which included first estimates for 2014 from the annual FDI survey and revised estimates for 2013. These will be incorporated into the next edition of Balance of Payments for the UK: Jan to March 2016, on 30 June 2016. Therefore FDI and current account balance statistics presented in this paper for 2013 and 2014 are indicative Balance of Payments estimates1, and will differ from those published as part of today’s Balance of Payments release. These indicative estimates assume all other components of the current account for 2013 and 2014 will remain unchanged. Further information on the coherence between statistics presented in the FDI publication and Balance of Payments was published in December: Foreign Direct Investment, Coherence between Balance of Payments Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2015 and the FDI 2014 Bulletin.

Figure 1: Components of the UK current account balance as a percentage of nominal GDP, 2009 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- FDI and current account figures for 2013 and 2014 make use of data from the recent FDI publication and are therefore indicative estimates.

Download this chart Figure 1: Components of the UK current account balance as a percentage of nominal GDP, 2009 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsNotes for Introduction

- Indicative Balance of Payments statistics presented in this article do not include newly revised estimates of holding of property. Further information can be found via this link. Users are advised that these revised estimates have no impact on FDI earnings and therefore the Current Account; however there is an impact on FDI assets and liabilities.

4. The continued decline in direct investment earnings

UK FDI earnings have made a positive contribution to the UK current account since 1997, partly offsetting negative contributions from the other major components. However, the positive contribution of FDI earnings has fallen since 2011, turning negative in 2015. Figure 2 presents the UK’s net FDI earnings, along with the underlying credits and debits. Credits refer to earnings on UK assets abroad, and debits for earnings made by a non-resident enterprises on assets held in the UK. Between 2011 and 2015, UK net FDI earnings deteriorated by £57.0 billion to a deficit of £3.5 billion. A decline in FDI credits over this period explains nearly 80% of the deterioration in net FDI earnings, with the remainder explained by increases in debits.

Figure 2: FDI credits, debits and earnings balance, 2009 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 2: FDI credits, debits and earnings balance, 2009 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsThe decline in net FDI earnings between 2014 and 2015 marks the fourth consecutive annual decline since 2011, continuing a broadly similar rate. Figure 3 shows the consistent decline of UK credits continued on a quarterly basis throughout 2015 – reaching £11 billion in Q4. Despite a decline in UK debits throughout Q2 and Q3, a recovery in Q4 coupled with falling FDI credits resulted in a negative FDI balance of £5 billion in Q4; a record low for UK net FDI earnings.

Figure 3: FDI credits, debits and earnings balance, Q1 2015 to Q4 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 3: FDI credits, debits and earnings balance, Q1 2015 to Q4 2015

Image .csv .xlsChanges in FDI earnings can reflect a change in the rate of return, a change in the stock of investment, or a combination of the two. As highlighted in previous analysis, the decline in FDI credits since 2011 has been entirely driven by a fall in the rate of return UK investors achieved on their overseas investments. In contrast, increases in FDI debits have been due to increased investment – potentially due to the more resilient rates of return achieved in the UK.

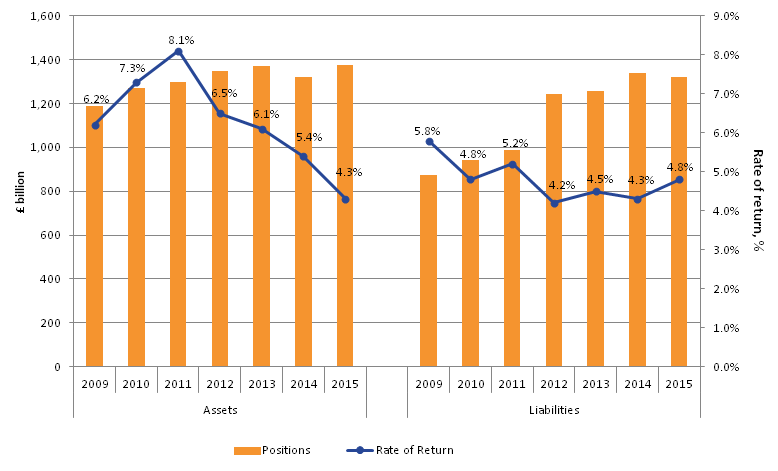

Figure 4 presents the rates of return of UK FDI assets and liabilities alongside the value of the stocks of investment. The value of FDI assets are relatively stable compared with liabilities between 2011 and 2015, increasing from £1,297.1 billion to £1,376.6 billion. Although the value of FDI assets has been stable, the rate of return has not; following a continuing downward trend from 8.1% in 2011 to 4.3% in 2015.

Figure 4: FDI positions and rates of return, 2009 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Rates of return are calculated by dividing earnings by positions.

Download this image Figure 4: FDI positions and rates of return, 2009 to 2015

.png (36.5 kB) .xlsx (15.0 kB)In contrast to assets, FDI liabilities experienced a notable increase from £986.5 billion to £1,322.1 billion between 2011 and 2015. The rise in liabilities does, however, appear to have softened in the most recent period, with the value in 2015 declining by £18.5 billion compared with 2014 – the first annual decline recorded since 2009.

The rate of return achieved on liabilities is more resilient than assets, falling from 5.2% in 2011 to 4.8% in 2015. The stark difference in performance between the rates of return of assets and liabilities, in conjunction with increased investment into the UK, explains the deterioration in the net FDI earnings.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Performance of the largest FDI investments

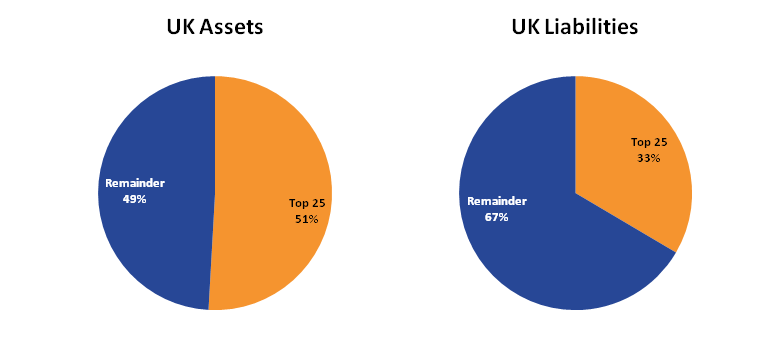

As highlighted in previous analysis by ONS, a small number of the largest multinational companies account for a large proportion of FDI earnings, and their performance has been a key factor in the deterioration of the UK current account. Figure 5 presents the proportion of FDI assets and liabilities accounted for by the largest 25 multinational companies1 and the remainder. The size of the company is defined by the net book value of its FDI assets. The top 25 are selected in each year for assets and liabilities independently, therefore the composition of multinational companies can change; although it should be noted that they are largely consistent over the period. The largest 25 multinational companies account for just over half of UK direct investment abroad, but only a third of direct investment into the UK. Therefore UK assets are more dependent upon the performance of large multinational companies than liabilities.

Figure 5: Proportion of UK assets and liabilities accounted for by the largest 25 multinational companies and the remainder, 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 5: Proportion of UK assets and liabilities accounted for by the largest 25 multinational companies and the remainder, 2015

.png (16.6 kB) .xlsx (14.2 kB)Figure 6 presents the UK credits and debits from the largest 25 multinational companies and the remainder. Credits from the 25 largest multinational companies undertaking FDI investment abroad has fallen from a peak of £58 billion in 2011 to £24 billion in 2015. Credits from the remaining multinational companies have also fallen but to a lesser extent, from £47 billion to £35 billion over the same period. The role of the largest 25 multinational companies investing in the UK is less notable, accounting for only £11 billion of UK debits in 2011, which then increased to £13 billion in 2015. The contribution of the remaining multinational companies is much larger, increasing from £40 billion to £50 billion over the same period.

Figure 6: UK credits and debits accounted for by the largest 25 multinational companies and the remainder, 2011 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 6: UK credits and debits accounted for by the largest 25 multinational companies and the remainder, 2011 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsThe importance of the largest 25 multinationals companies for UK FDI assets continued throughout 2015 – their contribution to UK credits fell from £10.4 billion in Q1 to £3.5 billion in Q4, as shown in Figure 7. In contrast, the contribution of the remaining multinational companies was broadly stable between Q1 and Q4, despite a stronger Q2 and Q3. Despite the largest 25 multinational companies investing in the UK impacting negatively on UK credits, the impact is considerably smaller for UK debits, which fell from £4.2 billion in Q1 2015 to £2.6 billion in Q4 2015.

Figure 7: UK credits and debits accounted for by the largest 25 multinational companies and the remainder, Q1 2015 to Q4 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Seasonal adjustments are applied evenly across all firm sizes

Download this chart Figure 7: UK credits and debits accounted for by the largest 25 multinational companies and the remainder, Q1 2015 to Q4 2015

Image .csv .xlsNotes for the Performance of the largest FDI investments

- The top 25 excluding banks, bank holding companies and property companies

6. The impact of commodity prices on FDI

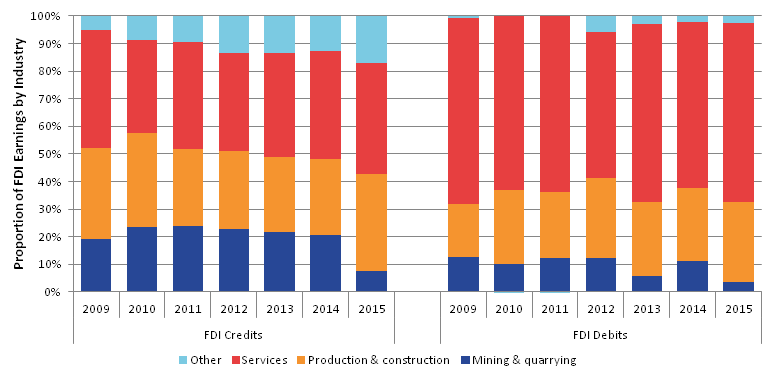

One explanation of the contrast in performance between UK FDI credits and debits is the industrial composition of assets and liabilities. Figure 8 presents total FDI earnings by the industry they are produced in1, and highlights some notable differences. On the assets side, the proportion of credits accounted for by the mining & quarrying industries2 has averaged around 22.9% between 2009 and 2014, before falling to 7.4% in 2015. In contrast, the proportion of debits accounted for by mining & quarrying is more than half that of credits, averaging 10.7% between 2009 and 2014, before falling to 3.4% in 2015.

The asymmetric industrial composition of assets and liabilities may help explain why the performance of credits has been weaker than debits since 2011. The impact of economic events, such as a decline in commodity prices, will differ depending on the industry in question.

A further distinction between FDI assets and liabilities is the proportion of debits that is accounted for by the services industries; services have accounted for approximately 62.6% of debits on average between 2009 and 2015, compared to 38.3% for credits.

Figure 8: Industrial composition of UK FDI earnings, 2009 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 8: Industrial composition of UK FDI earnings, 2009 to 2015

.png (28.4 kB) .xlsx (14.8 kB)Figure 9 presents the Commodity Fuel Index3, produced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which collates information on a range of commodity prices, most notably crude oil. Commodity prices remained broadly stable between 2011 and 2013, before declining in 2014 and 2015.

Figure 9: World commodities fuel prices index, 2011=100, 2009 to 2015

Source: International Monetary Fund

Notes:

- Commodity Fuel (energy) Index includes Crude oil (petroleum), Natural Gas, and Coal Price Indices, simple annual average.

Download this chart Figure 9: World commodities fuel prices index, 2011=100, 2009 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsTraditionally the amount the UK has generated from its overseas mining & quarrying assets has far exceeded the amount overseas investors earned from their UK based mining & quarrying investments. During their peak in 2011, FDI credits from mining & quarrying reached £24.9 billion, almost four times the amount of debits. This can be attributed to both a larger UK-owned market abroad and a higher rate of return received from high yielding assets, as the largest and most easily accessible natural resources are based outside of the UK.

A larger value of assets compared with liabilities makes UK FDI credits more exposed than debits to movements in global oil prices; UK FDI credits are likely to benefit when commodity fuel prices increase, and be adversely affected when they fall. This is evident in the recent fall in oil prices, especially between 2013 and 2015, when a 48.1% fall in commodity fuel prices coincided with UK FDI credits within the industry falling 75.3%.

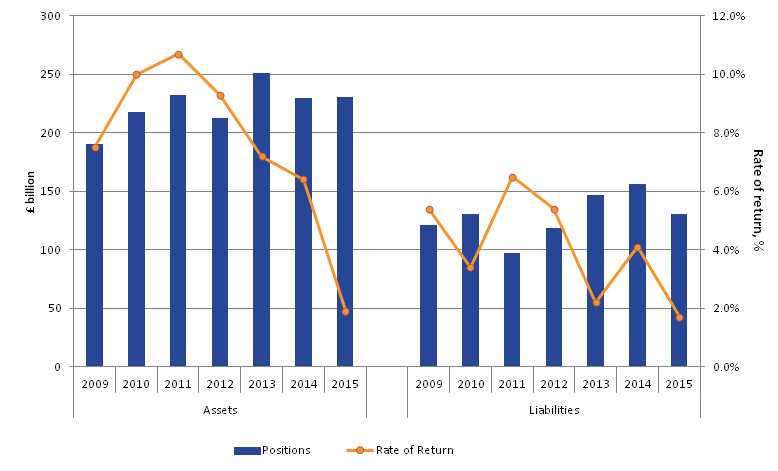

UK FDI credits from the mining & quarrying industries have experienced a notable decline between 2011 and 2015, falling by more than 80% to £4.5 billion over the period. The decline in credits over this period is almost fully explained by a fall in the rate of return, from a peak of 10.7% in 2011 to 1.9% in 2015. In contrast, the stock of assets held within the industry has remained relatively stable, falling slightly from £231.9 billion to £230.8 billion between 2011 and 2015.

Figure 10: Stock of mining & quarrying assets & liabilities and rates of return, 2009 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 10: Stock of mining & quarrying assets & liabilities and rates of return, 2009 to 2015

.png (35.3 kB) .xlsx (15.0 kB)FDI debits from mining & quarrying industries also fell between 2011 and 2015; however, their decline was notably smaller than credits in both absolute and percentage terms, falling by £4.1 billion (-65.1%) over the period, compared with the £20.4 billion fall in credits (-81.9%).

As already discussed, the smaller decline in absolute terms is due to the UK owning a larger stock of FDI assets in mining & quarrying compared with the stock of investment overseas investors own in the UK, therefore making the UK more exposed to changing commodity prices. However, the smaller change in percentage terms is likely to reflect two factors. First, although there is some evidence that rates of return have followed a broadly downward trend between 2011 and 2015, the fall was from a lower starting place, 6.5% compared with 10.7%. This reflects that the UK’s overseas assets within this industry have yielded better returns than liabilities. Second, the rate of return generated by mining & quarrying liabilities has been lower and more volatile compared to assets. This is potentially due to the more challenging nature of North Sea oil extraction; mining & quarrying production in the UK has followed a broadly downward trend in output since 1997.

Movements in commodity prices can have varying degrees of impact depending on the industry. For example, the earnings of producers of raw and refined oil are likely to be negatively affected by a fall in prices, as earnings in such industries rely on the unit sale price of their products. In contrast, industries that consume a large amount of raw and refined product as part of the production process may benefit from lower input costs and, all else being equal, potentially higher profit margins. However, it should be noted that a range of other factors, such as competitiveness and global demand, can also impact profitability. Figures 11 and 12 decompose UK assets and liabilities into four ‘oil intensity’ categories: producers of raw and refined oil, and low oil intensity, medium oil intensity and high oil intensity industries. It is reasonable to assume that a fall in oil prices may negatively impact the earnings of the first category, but benefit the latter two4.

The production of raw and refined oil products accounted for 16.7% of UK assets on average over the period compared with 11.2% of UK liabilities. Therefore a larger proportion of UK assets are likely to be negatively exposed to the fall in oil prices that occurred from late 2014 onwards. In contrast, medium and high oil intensity industries made up a smaller proportion of UK assets (46.8%) compared with UK liabilities (57.2%) – these industries are likely to benefit from a fall in oil prices as such a change may result in lower input costs and therefore increased profitability.

The larger proportion of UK assets accounted for by raw & refined oil producers makes UK investors abroad more likely to be adversely affected by a fall in oil prices. In contrast, a larger proportion of UK liabilities accounted for by medium and high oil intensity industries makes overseas investors more likely to benefit from a fall in oil prices. Therefore, the UK’s overall FDI earnings balance is likely to be adversely affected by a fall in oil prices.

Figure 11: Composition of FDI assets by SIC oil intensity, percentage of total, 2009 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 11: Composition of FDI assets by SIC oil intensity, percentage of total, 2009 to 2015

Image .csv .xls

Figure 12: Composition of FDI liabilities by SIC oil intensity, percentage of total, 2009 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 12: Composition of FDI liabilities by SIC oil intensity, percentage of total, 2009 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsTo further examine the impact of falling global commodity prices, Figure 13 and Figure 14 present the percentage change of an FDI weighted commodity price index5, alongside the percentage change of UK credits and debits generated from industries that produce either raw or basic materials6, plus the percentage change of total FDI credits & debits. As expected, the relationship between the commodity price index and credits & debits generated from raw and basic materials producers is stronger than its relationship with total FDI credits & debits. However, when focusing on FDI earnings from this particular industry subset, the relationship is stronger for UK credits. Both follow a downward trend, similar to the associated price indices, although the relationship is considerably stronger for UK investment abroad.

The contrast in the relationship between UK FDI credits and debits with world commodity prices is likely to reflect that UK assets comprise a larger proportion of high yielding producers of raw and basic materials compared with UK liabilities.

Figure 13: Percentage change in total UK credits, selected commodity based UK credits, and commodities prices index, 2010 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 13: Percentage change in total UK credits, selected commodity based UK credits, and commodities prices index, 2010 to 2015

Image .csv .xls

Figure 14: Percentage change in total UK debits, selected commodity based UK debits and commodities prices index, 2010 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 14: Percentage change in total UK debits, selected commodity based UK debits and commodities prices index, 2010 to 2015

Image .csv .xlsNotes for The impact of commodity prices on FDI

- Industry groupings used in this section are provided in Table 1 in the annex.

- Mining & Quarry refers to section B according to Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) 2007

- Commodity Fuel (energy) Index includes Crude oil (petroleum), Natural Gas, and Coal Price Indices, simple annual average.

- The oil intensity of an industry is defined by the percentage of crude petroleum, natural gas, metal ores, coke and refined petroleum products in total industry intermediate consumption (2015 Input-output supply and use tables).

- This has been calculated using the weighted shares of assets/liabilities for industries in which appropriate commodity prices are available (further detail of the SIC and price indices used can be found in the annex).

- See Tables 2 and 3 in annex for a list of industries and their corresponding commodity price index.