Cynnwys

- Main points

- Things you need to know about this release

- Producer price inflation summary

- Following the recent strengthening of sterling, input costs have continued to fall back from their peak

- The rate of increase in factory gate prices appears to be stabilising now that manufacturing input costs have largely fallen month-on-month since January

- Price falls for coke and refined petroleum products have been offset by rising prices for food products and computers, electrical and optical equipment

- Improvements to the Import and Export Price Indices (IPI and EPI) and Services Producer Price Indices (SPPI): June 2017

- Links to related statistics

- Quality and methodology

1. Main points

The rate of increase in factory gate prices appears to be stabilising now that manufacturing input costs have largely fallen month-on-month since January.

The annual rate of factory gate price inflation (output prices) remained at 3.6% for the third consecutive month and slowed on the month to 0.1%, from 0.4% in March and April.

The annual rate of inflation for materials and fuels (input prices) fell back to 11.6% in May, continuing its decline from 19.9% in January 2017 following the recent strength of sterling.

Recent price declines for coke and refined petroleum products leaving the factory gate have been offset by rising prices for food products and computers, electrical and optical equipment.

2. Things you need to know about this release

The factory gate price (output price) is the amount received by UK producers for the goods that they sell to the domestic market. It includes the margin that businesses make on goods, in addition to costs such as labour, raw materials and energy, as well as interest on loans, site or building maintenance, or rent.

The input price measures the price of materials and fuels bought by UK manufacturers for processing. It includes materials and fuels that are both imported or sourced within the domestic market. It is also not limited to materials used in the final product, but includes what is required by businesses in their normal day-to-day running, such as fuels.

Index numbers shown in the main text of this bulletin are on a net sector basis. The index for any industry relates only to transactions between that industry and other industries; sales and purchases within industries are excluded.

Indices relate to average prices for a month. The full effect of a price change occurring part way through any month will only be reflected in the following month’s index.

All index numbers exclude VAT. Excise duty (on cigarettes, manufactured tobacco, alcoholic liquor and petroleum products) is included, except where labelled otherwise.

Each Producer Price Index (PPI) has two unique identifiers: a 10-digit index number, which relates to the Standard Industrial Classification code appropriate to the index and a 4-character alpha-numeric code, which can be used to find series when using the time series dataset for PPI.

Every 5 years, producer price indices are rebased and weights updated to reflect industry changes.

Figures for the latest 2 months are provisional and the latest 5 months are subject to revisions in light of (a) late and revised respondent data and (b) for the seasonally adjusted series, revisions to seasonal adjustment factors are re-estimated every month. A routine seasonal adjustment review is normally conducted in the autumn each year.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Producer price inflation summary

Figure 1: Input PPI and output PPI, May 2002 to May 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 1: Input PPI and output PPI, May 2002 to May 2017, UK

Image .csv .xlsOver the past 15 years, the input Producer Price Index (PPI) has experienced large peaks and troughs and strong overall growth, driven by global movements in prices for crude oil and commodities (Figure 1). Between May 2002 and May 2017, input prices increased 72%, mainly fuelled by crude oil prices that rose 127% over the period. Output prices increased 31% across the same period.

Comparing prices today with those prior to the downturn peak in June 2008, input prices were 1.1% lower in May 2017, while output prices were up 12.4% across the period.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Following the recent strengthening of sterling, input costs have continued to fall back from their peak

Table 1: Input prices, index values, growth rates and percentage point changes: May 2016 to May 2017

| UK | |||||

| All materials and fuels purchased (K646) | |||||

| Change in the | |||||

| PPI Index | 1-month | 12-month | 12-month rate | ||

| (2010=100) | rate | rate | (percentage points) | ||

| 2016 | May | 94.8 | 2.3 | -4.3 | 2.8 |

| Jun | 96.4 | 1.7 | -0.5 | 3.8 | |

| Jul | 99.5 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.7 | |

| Aug | 99.8 | 0.3 | 7.8 | 3.6 | |

| Sep | 100.2 | 0.4 | 7.6 | -0.2 | |

| Oct | 104.6 | 4.4 | 12.4 | 4.8 | |

| Nov | 104.0 | -0.6 | 13.5 | 1.1 | |

| Dec | 106.5 | 2.4 | 16.6 | 3.1 | |

| 2017 | Jan | 108.0 | 1.4 | 19.9 | 3.3 |

| Feb | 108.0 | 0.0 | 19.3 | -0.6 | |

| Mar | 107.5 | -0.5 | 16.8 | -2.5 | |

| Apr | 107.2 | -0.3 | 15.6 | -1.2 | |

| May | 105.8 | -1.3 | 11.6 | -4.0 | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Series are not seasonally adjusted. | |||||

Download this table Table 1: Input prices, index values, growth rates and percentage point changes: May 2016 to May 2017

.xls (20.0 kB)The latest figures suggest an overall easing of input cost pressures in the manufacturing sector. In the 12 months prior to February 2017 prices rose every month bar one, which led manufacturers to raise prices for goods leaving the factory gate; however, recent month-on-month falls mean input costs overall are now below the level they were back in December 2016.

The annual rate fell for the fourth month in a row in May 2017 representing an 8.3 percentage point decline from January 2017. The fall of 4.0 percentage points in May compares to a 2.6 average percentage point movement between May 2016 and April 2017. The only larger movements were in July and October 2016 when prices were growing rapidly as exchange rate movements were passed through.

We have now also seen 3 months of falling prices month-on-month. The 1.3% month-on-month decline in May represents an acceleration of this trend and has led to price levels overall, as defined by the index value, being lower than they were back in December 2016 when the index stood at 106.5.

Table 2: Imported materials and fuels purchased and sterling effective exchange rate, index values, growth rates and percentage point change to the 12-month rate: May 2016 to May 2017

| UK | ||||||||||||

| Imported materials and fuels purchased (K64F) | Sterling effective exchange rate - month average | |||||||||||

| PPI Index (2010=100) | 1-month rate | 12-month rate | Change in the 12-month rate(percentage points) | 1-month rate | 12-month rate | |||||||

| 2016 | May | 92.9 | 1.1 | -2.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 | -5.1 | |||||

| Jun | 94.7 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 3.3 | -2.0 | -7.8 | ||||||

| Jul | 98.5 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | -6.5 | -14.9 | ||||||

| Aug | 98.8 | 0.3 | 9.2 | 3.2 | -1.3 | -16.2 | ||||||

| Sep | 99.0 | 0.2 | 8.9 | -0.3 | 0.4 | -14.3 | ||||||

| Oct | 103.5 | 4.5 | 14.0 | 5.1 | -5.1 | -18.4 | ||||||

| Nov | 101.9 | -1.5 | 14.6 | 0.6 | 2.7 | -17.9 | ||||||

| Dec | 103.7 | 1.8 | 17.4 | 2.8 | 2.1 | -14.5 | ||||||

| 2017 | Jan | 106.0 | 2.2 | 20.2 | 2.8 | -1.6 | -13.0 | |||||

| Feb | 105.5 | -0.5 | 19.2 | -1.0 | 0.8 | -10.4 | ||||||

| Mar | 106.1 | 0.6 | 17.0 | -2.2 | -1.3 | -10.7 | ||||||

| Apr | 105.4 | -0.7 | 14.7 | -2.3 | 2.2 | -7.8 | ||||||

| May | 103.9 | -1.4 | 11.8 | -2.9 | 0.5 | -9.2 | ||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||||||||||||

| The sterling effective exchange rate source: Bank of England | ||||||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||||

| 1. Series are not seasonally adjusted. | ||||||||||||

| 2. The sterling effective change rate measures the changes in the strength of sterling relative to a basket of other currencies | ||||||||||||

| 3. The sterling effective exchange rate is only indicative of the rates applied to producer prices. This is because the sterling effective exchange rate is a trade weighted index that represents all UK trade, whereas producer prices reflect transactions in the production sector. | ||||||||||||

Download this table Table 2: Imported materials and fuels purchased and sterling effective exchange rate, index values, growth rates and percentage point change to the 12-month rate: May 2016 to May 2017

.xls (22.5 kB)Imported materials and fuels account for around two-thirds of input PPI in terms of index weight, suggesting the UK manufacturing sector imports most of the materials and fuels it uses in the manufacturing process. The devaluation of sterling that started in early 2016 has therefore fed through to higher input costs for the UK manufacturing sector. Since October 2016, however, when the sterling effective annual rate was down 18.4%, we have seen this rate ease off to a decline of 9.2% in May 2017, which has translated into falling prices for imported materials and fuels.

Table 3: Input prices, growth rates: May 2017

| UK | ||

| Product group | Percentage change | |

| 1-month | 12-month | |

| rate | rate | |

| Fuel including Climate Change Levy | 0.1 | 6.7 |

| Crude oil | -7.6 | 20.0 |

| Home food materials | 0.0 | 13.1 |

| Imported food materials | 1.1 | 12.8 |

| Other home-produced materials | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| Imported metals | -2.8 | 21.1 |

| Imported chemicals | -0.3 | 9.7 |

| Imported parts and equipment | -0.1 | 7.1 |

| Other imported materials | -0.2 | 8.9 |

| All manufacturing | -1.3 | 11.6 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||

Download this table Table 3: Input prices, growth rates: May 2017

.xls (25.1 kB)

Figure 2: Input PPI, contribution to 1-month and 12-month growth rate, May 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 2: Input PPI, contribution to 1-month and 12-month growth rate, May 2017, UK

Image .csv .xlsFigure 2 shows contributions by industry to the monthly and annual rate of input price inflation. Crude oil provided the largest upward contribution to the annual rate and the largest downward contribution to the monthly rate. Crude oil prices fell 7.6% in May (Table 3) and have mostly fallen month-on-month since January 2017.

Home food materials and imported metal prices provided the second and third largest contributions to the annual rate, with 1.91 and 1.55 percentage points respectively.

The annual rate for home food materials, although positive for the past 13 months, fell to 13.1% in May 2017 (Table 3) from 25.0% in April, which was the highest annual increase since July 2008. The main contributors to the rise in home food materials were domestic products used in crop and animal production.

The annual rate of growth for imported metals has also fallen back from an all-time record high of 37.2% in January 2017. In May 2017, prices rose 21.1% on the year, although fell 2.8% on the month, which is the second monthly decline in prices since June 2016. The recent strengthening of sterling is the most likely factor for slowing growth. For further analysis on metal prices please refer to section 4 of the February Producer Price Inflation release.

Figure 3: Input PPI, contribution to change in the annual rate, May 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 3: Input PPI, contribution to change in the annual rate, May 2017, UK

Image .csv .xls5. The rate of increase in factory gate prices appears to be stabilising now that manufacturing input costs have largely fallen month-on-month since January

Table 4: Output prices, index values, growth rates and percentage point changes: May 2016 to May 2017

| UK | |||||

| All manufactured products (JVZ7) | |||||

| Change in the | |||||

| PPI Index | 1-month | 12-month | 12-month rate | ||

| (2010=100) | rate | rate | (percentage points) | ||

| 2016 | May | 106.6 | 0.1 | -0.5 | 0.0 |

| Jun | 106.9 | 0.3 | -0.2 | 0.3 | |

| Jul | 107.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | |

| Aug | 107.3 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | |

| Sep | 107.6 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.4 | |

| Oct | 108.3 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.9 | |

| Nov | 108.4 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.3 | |

| Dec | 108.7 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 0.5 | |

| 2017 | Jan | 109.3 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 0.7 |

| Feb | 109.5 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 0.1 | |

| Mar | 109.9 | 0.4 | 3.6 | -0.1 | |

| Apr | 110.3 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 0.0 | |

| May | 110.4 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 0.0 | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. Series is not seasonally adjusted. | |||||

Download this table Table 4: Output prices, index values, growth rates and percentage point changes: May 2016 to May 2017

.xls (28.7 kB)The latest figures suggest the recent period of rapidly increasing factory gate prices may have come to an end. The annual rate of inflation for goods leaving the factory gate was unchanged at 3.6% in May 2017 and has remained largely flat since January 2017. Month-on-month inflation slowed to 0.1% in May following increases of 0.4% in March and April.

Table 5: Output prices, growth rates: May 2017

| UK | ||

| Product group | Percentage Change | |

| 1-month | 12-month | |

| rate | rate | |

| Food products | 0.9 | 5.6 |

| Tobacco and alcohol (incl. duty) | 0.1 | 3.2 |

| Clothing, textile and leather | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Paper and printing | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Petroleum products (incl. duty) | -2.3 | 9.1 |

| Chemical and pharmaceutical | 0.0 | 4.8 |

| Metal, machinery and equipment | 0.1 | 4.0 |

| Computer, electrical and optical | 0.0 | 3.5 |

| Transport equipment | 0.1 | 3.6 |

| Other manufactured products | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| All manufacturing | 0.1 | 3.6 |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||

Download this table Table 5: Output prices, growth rates: May 2017

.xls (25.6 kB)

Figure 4: Output PPI, contribution to 1-month and 12-month growth rate, May 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: Output PPI, contribution to 1-month and 12-month growth rate, May 2017, UK

Image .csv .xlsAll industries showed upward contributions to the annual rate. Food products had an annual growth rate of 5.6% (Table 5) and showed an upward contribution of 0.85 percentage points to the PPI output annual rate (Figure 4). The largest contributor to growth was dairy products, which increased 18.7% on the year. The annual growth rate for food products has been positive since October 2016, following 29 months of falling prices. For further analysis on food prices please refer to section 6 of this release and section 4 of the January Producer Price Inflation release.

Petroleum products provided the second largest upward contribution to the annual rate with 0.62 percentage points, driven mainly by an increase in the prices of diesel and gas oil.

Transport equipment also showed a large annual increase of 3.6% (Table 5), driven mainly by prices within the manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers. For further analysis of prices within the manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers please refer to section 4 of the March Producer Price Inflation release.

Figure 5: Output PPI, contribution to change in the annual rate, May 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 5: Output PPI, contribution to change in the annual rate, May 2017, UK

Image .csv .xls6. Price falls for coke and refined petroleum products have been offset by rising prices for food products and computers, electrical and optical equipment

Figure 6: Annual rate of PPI factory gate inflation and contributions to the rate, May 2015 to May 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Contributions to the annual change rate may not add up to the rate exactly due to rounding.

Download this chart Figure 6: Annual rate of PPI factory gate inflation and contributions to the rate, May 2015 to May 2017, UK

Image .csv .xlsFigure 6 shows the annual rate of factory gate price inflation along with contributions to the rate. Following the return to positive growth in July 2016, the rate increased month-on-month until January 2017. Since then the rate has been relatively flat, falling 0.1 percentage points to 3.6% in March and then remaining at that level.

However, while the headline rate has flattened since January, the balance of contributions across industries has changed. Falling prices within the coke and refined petroleum industry have been offset by rising prices from food producers and manufacturers of computers, electrical and optical equipment.

Since February 2017, contributions from the coke and refined petroleum industry have fallen. By May 2017, the industry was no longer the largest contributor to the annual rate despite being the largest contributor for 20 of the 25 periods between May 2015 and May 2017.

The fall in prices is likely due to falling prices for inputs of crude oil, which represent an important cost in the production of coke and refined petroleum products. Prices for inputs of crude oil into manufacturing have largely fallen month-on-month since January 2017 and were down 7.6% in May (Table 3).

The fall in crude oil prices is a result of the combined effect of falling US dollar prices for crude on the world market and the impact of sterling appreciating against the dollar since October 2016. In dollar terms, crude oil prices have fallen from an average of $55 per barrel in January 2017 to around $50 in May. According to average monthly exchange rates published by the Bank of England (BoE), sterling has appreciated 4.9% against the dollar since October 2016. All else equal, an appreciation of sterling against the dollar leads to dollar-traded commodities such as crude oil becoming cheaper in sterling terms.

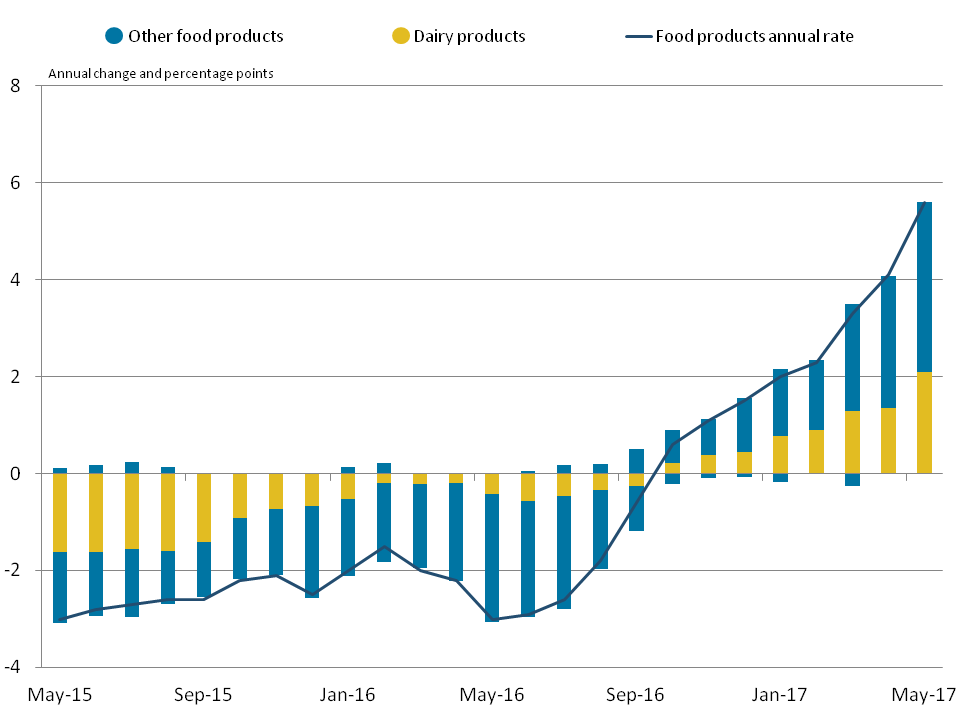

Figure 7: Annual rate of factory gate inflation for food producers and contributions to the rate, May 2015 to May 2017, UK

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 7: Annual rate of factory gate inflation for food producers and contributions to the rate, May 2015 to May 2017, UK

.png (11.3 kB) .xls (11.1 kB)Figure 7 shows the annual rate of factory gate price inflation for food producers, along with the contribution to the rate from dairy products. Since November 2016, dairy products have been the largest contributor to the annual rate of inflation for food producers. In May 2017, prices were up 18.7% on the year and 4.7% on the month, the fastest rate of growth since June 2008 and October 2007 respectively.

The rise in prices for dairy products is mostly a result of supply and demand issues related to UK milk production, although rising input costs, particularly energy prices, might also be a factor. The same price pressures are also present across the EU, which may have put further pressure on UK prices. According to the latest figures from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), UK milk production was down 3.2% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2017. The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (ADHB) put the fall down to poor weather and grazing conditions.

In terms of the EU, Eurostat reported that production of raw milk was down 2.3% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2017 and that prices in January 2017 grew at their fastest rate for 2 years.

The next largest factor offsetting falling prices in the coke and refined petroleum industry came from rising prices set by manufacturers of computers, electrical and optical equipment. This may be a result of higher input costs for electrical components following the overall devaluation of sterling over the past 2 years.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Improvements to the Import and Export Price Indices (IPI and EPI) and Services Producer Price Indices (SPPI): June 2017

Please note that we have made some changes to the scheduled programme of sample improvement release dates that was announced in November 2016. The sample updates will be introduced in phases starting with updates to the Export Price Index (EPI) in July 2017 (June 2017 period).

The changes relate to when some of the sample updates for specific divisions are scheduled to be introduced; Table 1 (Sample Improvement Release Dates) within the November 2016 article, which can be accessed via the link above, has now been updated to reflect these changes.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys9. Quality and methodology

The PPI Quality and Methodology Information document contains important information on:

- the strengths and limitations of the data and how it compares with related data

- users and uses of the data

- how the output was created • the quality of the output including the accuracy of the data

If you would like more information about the reliability of the data, a PPI standard errors article was published 20 March 2017. The article presented the calculated standard errors of the Producer Price Index (PPI) during the period January 2016 to December 2016, for both month-on-month and 12-month growth.

Guidance on using indices in indexation clauses has been published. It covers producer prices, services producer prices and consumer prices.

An up-to-date manual for the PPI, including the import and export index, is now available. PPI methods and guidance provides an outline of the methods used to produce the PPI as well as information about recent PPI developments.

Gross sector basis figures, which include intra-industry sales and purchases, are shown in PPI dataset Tables 4 and 6.

The detailed input indices of prices of materials and fuels purchased by industry (PPI dataset Table 6) do not include the Climate Change Levy (CCL). This is because each industry can, in practice, pay its own rate for the various forms of energy, depending on the various negotiated discounts and exemptions that apply.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys