Cynnwys

- Main points

- Statistician’s comment

- Summary

- Core consumer inflation remained unchanged in May 2019 while non-core inflation fell slightly

- A fall in the growth of crude oil prices in May 2019 has been driven by price movements a year ago

- Annual growth in rents and house prices in London have risen slightly

- Authors

1. Main points

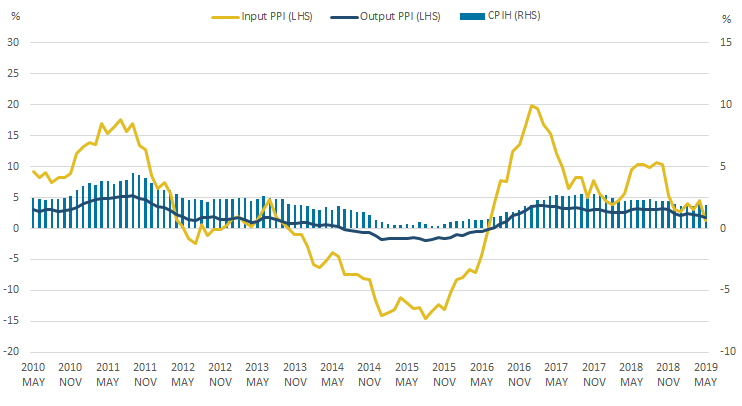

The 12-month growth rate of the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) fell to 1.9% in May 2019, down from 2.0% in April 2019.

The output Producer Price Index (output PPI) grew by 1.8% in the 12 months to May 2019, down from 2.1% in the 12 months to April 2019.

The input Producer Price Index (input PPI) grew by 1.3% in the 12 months to May 2019, down from 4.5% in the 12 months to April 2019.

The fall in consumer price growth was driven largely by non-core components, with growth in core inflation remaining unchanged since April 2019.

Base effects are driving the latest change in the 12-month growth rate of crude oil in input PPI.

Annual growth in private rental prices in London was 0.9%, its highest rate since September 2017.

2. Statistician’s comment

Commenting on today’s inflation figures, Head of Inflation Mike Hardie said:

“Inflation eased in May, as travel prices such as air fares fell back after their Easter highs in April. The overall rate of inflation has remained steady since the beginning of the year.

“Annual house price growth remained subdued but was strong in Wales, which showed a pronounced increase on the month. In London, house prices continued to fall over the year but rental price growth there strengthened.”

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Summary

Figure 1 shows that the 12-month growth rate of the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) was 1.9% in May 2019, down from 2.0% in April 2019. The largest downward contributions to change in the 12-month rate came from transport, predominantly transport services, with a further small downward contribution from alcohol and tobacco. These downward effects were partially offset by small upward contributions from a variety of categories, including recreation and culture, restaurants and hotels, food and non-alcoholic beverages, and furniture, household equipment and maintenance.

The output Producer Price Index (output PPI) grew by 1.8% in the 12 months to May 2019, down from 2.1% in the 12 months to April 2019. Petroleum products made the largest downward contribution to the change in the 12-month growth rate, while food products and tobacco and alcohol had an upward effect.

The input Producer Price Index (input PPI) grew by 1.3% in the 12 months to May 2019, down from 4.5% in the 12 months to April 2019. None of the components made a positive contribution to the change in the annual input rate, with crude oil making the largest downward contribution.

Figure 1: The 12-month growth rates of CPIH, input PPI and output PPI all fell between April and May 2019

12-month growth rates for input PPI and output PPI (left-hand side), and CPIH (right-hand side), UK, May 2010 to May 2019

Source: Office for National Statistics – Producer Price Index and Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers' housing costs

Notes:

- These data are also available within the Dashboard: Understanding the UK economy.

Download this image Figure 1: The 12-month growth rates of CPIH, input PPI and output PPI all fell between April and May 2019

.png (24.7 kB) .xlsx (21.9 kB)4. Core consumer inflation remained unchanged in May 2019 while non-core inflation fell slightly

The Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH)1 can be split into two broad categories of inflation – core and non-core. Core CPIH strips out some of the most volatile components of CPIH to show underlying trends in the rest of the basket. Core components account for around 84% of the CPIH basket, with non-core components making up the remaining 16%. The non-core series consists of food and non-alcoholic beverages, alcoholic beverages and tobacco, and electricity, gas, and other fuels, and fuels and lubricants, the latter two groupings collectively labelled as “energy”.

In May 2019, the 12-month growth rate of CPIH was 1.9%, down slightly from 2.0% in April 2019. This change was driven by the change in the 12-month growth rate of non-core CPIH, which also fell, from 3.4% in April 2019 to 3.3% in May 2019, while core inflation remained unchanged at 1.7%.

Over recent months, core inflation has been relatively flat, with the 12-month growth rate staying at 1.8% from September 2018 to March 2019 before falling slightly to 1.7% in April and May 2019. By contrast, the 12-month growth rate of non-core CPIH has risen sharply in recent months, from a low of 1.6% in January 2019 to 3.4% in April 2019. This follows a period of falling growth in the non-core series, however, reflecting the underlying volatility of non-core components.

In January 2019, the 12-month growth rate of non-core CPIH was lower than the 12-month growth rate of core CPIH for the first time since December 2016. Figures 3 and 4 explore the drivers of movements in the contributions of core and non-core CPIH to all items CPIH.

Figure 2: Non-core CPIH has been growing more quickly than core CPIH in recent months

12-month growth rates for all items CPIH, core CPIH and non-core CPIH, UK, January 2016 to May 2019

Source: Office for National Statistics – Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs

Notes:

- Non-core CPIH includes: food and non alcoholic beverages; alcoholic beverages and tobacco; electricity, gas, liquid fuels, solid fuels; and fuels and lubricants.

Download this chart Figure 2: Non-core CPIH has been growing more quickly than core CPIH in recent months

Image .csv .xlsFigure 3 shows the contributions that each of the components of non-core CPIH have made to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH in each month since January 2016. All three components of non-core CPIH have made positive contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH since February 2017.

Energy has shown the largest variation in its contribution to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH over the period, with its contribution ranging from negative 0.38 percentage points in March 2016 to positive 0.54 percentage points in October 2018. Recent movements in non-core CPIH have been driven largely by energy, which has seen large movements, while contributions from food and non-alcoholic beverages, and alcoholic beverages and tobacco have been relatively stable in recent months.

Consumer prices for gas and electricity have been subject to regulatory changes in recent months, with the introduction of a price cap in January 2019 and a change in the cap in April 2019.

Figure 3: Energy has generally been the largest contributor of all the non-core components and is the biggest driver of movements in non-core CPIH

Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of all items CPIH from non-core CPIH components, UK, January 2016 to May 2019

Source: Office for National Statistics – Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs

Notes:

- Energy includes: electricity, gas, liquid fuels, solid fuels and fuels and lubricants.

Download this chart Figure 3: Energy has generally been the largest contributor of all the non-core components and is the biggest driver of movements in non-core CPIH

Image .csv .xlsAlcoholic beverages and tobacco has made consistently positive contributions to the 12-month growth rate over the period and has seen the least volatility in its contributions, which have ranged from 0.02 percentage points in June 2016 to 0.19 percentage points in November 2018.

Figure 4 shows contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH from the components of core CPIH since January 2016. The net contribution from core components of CPIH has been positive throughout the period and has shown relatively little variation compared with non-core CPIH.

For most of the period, housing and water has made the largest contribution to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH. The only other components that have made larger contributions in individual months are transport (excluding motor fuels), and recreation and culture.

Figure 4: The contributions of transport, and recreation and culture have generally been increasing throughout the period

Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of all items CPIH from core CPIH components, UK, January 2016 to May 2019

Source: Office for National Statistics – Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs

Notes:

- Housing and water is the component housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels excluding gas, electricity and other fuels, which are part of the non-core component energy.

- Transport excludes fuels and lubricants.

- The “other” component includes: health; communication; education and miscellaneous goods and services.

Download this chart Figure 4: The contributions of transport, and recreation and culture have generally been increasing throughout the period

Image .csv .xlsTransport has made increasing contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH over much of the period and is one of the more volatile components of core CPIH. Although this transport component excludes fuels and lubricants, which are included in the energy component of non-core CPIH, it contains other elements, such as transport services, that are also affected by movements in prices for fuels and likely account for its volatility.

The component that has seen the largest variation in its contribution to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH over the period is recreation and culture, which has ranged from a contribution of negative 0.02 percentage points in March 2016 to positive 0.43 percentage points in August 2018. Volatility in recreation and culture is driven largely by computer games, which see large variations in chart prices when new games are released.

Notes for: Core consumer inflation remained unchanged in May 2019 while non-core inflation fell slightly

- The Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) differs from the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) through its inclusion of costs associated with owning, maintaining and living in one’s own home, known as owner occupiers’ housing costs (OOH), as well as Council Tax. Rental equivalence is used to estimate the cost associated with living in one’s own home.

5. A fall in the growth of crude oil prices in May 2019 has been driven by price movements a year ago

The 12-month growth rate of the crude oil component of the input Producer Price Index (PPI) fell to negative 2.9% in May 2019, down from positive annual growth of 8.8% in April 2019. This is despite the fact that prices for the crude oil component actually rose slightly between April and May 2019. Similar base effects were seen last month in the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH).

The 12-month growth rate of prices depends on their movements in the current month and in the same month a year ago. This allows like-for-like comparisons to be made without seasonal price movements having large effects on the growth rate but, for volatile components like crude oil, this can lead to even greater volatility in price growth rates as prices, and their movements, may be very different from one year to the next.

Figure 5 shows movements in the 12-month growth rate for the crude oil component of input PPI and the contributions to the 12-month growth rate from current month price movements and the base effect, which reflects how prices moved a year ago.

Figure 5: A fall in crude oil price growth in May 2019 has been driven by price movements a year ago when prices were increasing more quickly

12-month growth in the crude oil component of input PPI, by current month and base effects, UK, January 2018 to May 2019

Source: Office for National Statistics – Producer Price Index

Download this chart Figure 5: A fall in crude oil price growth in May 2019 has been driven by price movements a year ago when prices were increasing more quickly

Image .csv .xlsCrude oil made by far the largest downward contribution to the change in the 12-month growth rate of input PPI between April and May 2019. This reflects not only that prices were lower in May 2019 than in May 2018, but also that prices rose more sharply between April and May 2018 than they did between April and May 2019.

Price growth for crude oil has been relatively low in recent months but has ticked up somewhat from the negative current month effects seen in November and December 2018. This may reflect the decision by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), in December 2018, to cut production of crude oil, removing 1.2 million barrels a day from the market. Crude oil prices are volatile in general and subject to a range of factors including global political tensions, as seen this week in the Gulf of Oman.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Annual growth in rents and house prices in London have risen slightly

Annual growth in the Index of Private Housing Rental Prices (IPHRP) in London rose to 0.9% in May 2019, its highest rate since September 2017. This continues the trend of gradually increasing annual growth since December 2018 but follows six months from May to October 2018 where rental prices were falling on the year.

Increasing rental prices suggest that demand for rental properties is likely to be outstripping supply. This is likely due to increasing tenant demand in London (PDF, 593KB), as reported by the Royal Institution for Chartered Surveyors (RICS) in September 2018. The demand for and supply of rental properties is also linked to movements in the housing market, as landlords decide whether to buy or sell rental properties and potential renters weigh up the relative affordability of renting or purchasing a property.

Figure 6 shows movements in the annual growth rate for house prices and rental prices in London. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) rent measure, the IPHRP, is a “stock” measure of rents – capturing price information for the entire private rented sector. The UK House Price Index (HPI), by contrast, is a “flow” measure, capturing only the part of the housing market that is changing as newly marketed properties are bought and sold. For this reason, we would expect the HPI series to reflect changes in the wider housing market more quickly than the IPHRP series.

Figure 6: Annual growth in the Index of Private Housing Rental Prices (IPHRP) in May 2019 was the highest since September 2017

12-month growth rates in house prices and private housing rental prices, London, January 2014 to May 2019

Source: Office for National Statistics – Index of Private Housing Rental Prices, HM Land Registry – UK House Price Index

Notes:

- The latest data available for house price growth are April 2019.

Download this chart Figure 6: Annual growth in the Index of Private Housing Rental Prices (IPHRP) in May 2019 was the highest since September 2017

Image .csv .xlsAnnual house price growth in London rose slightly in April 2019 but remained negative for the 14th consecutive month at negative 1.2%. This continues a broadly downward trend in London house price growth that started in 2014.

This fall in house prices may mean that purchasing a property is more affordable for first-time buyers who would otherwise be renting, thereby reducing demand for rental properties. But the fall also needs to be seen in the context of historically high price growth in London, which, prior to its recent downturn, peaked at over 20% annual growth in August 2014. Prices in April 2019 are still over 33% higher than they were in January 2014 and may remain unaffordable for many would-be first-time buyers.

Falling house prices are also likely to affect the supply of properties for sale, as homeowners who may otherwise choose to sell their property are put off by the prospect of a lower sale value. In May 2019, RICS reported that stock on sales agents’ books fell to a new low at a national level. This may reduce the options for potential buyers even if the available properties become more affordable.

Landlords face different considerations to owner-occupiers and there is evidence to suggest that some are leaving the market, possibly reflecting recent legislative changes as well as falls in rental returns. London has historically had a relatively large rental market, with buy-to-let properties making up a higher proportion of property sales than in other parts of the country, so the effect of legislative changes may have a larger impact in London than elsewhere.

Overall, RICS report that tenant demand is slowly increasing, while landlord instructions remain low. As such, recent low house price growth and rental price growth likely reflects general weakness in the market rather than oversupply.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys