Cynnwys

- Main points

- Statistician’s comment

- Summary

- The CPIH historical series provides long-term insight into price trends

- Presenting the historical CPIH alongside macroeconomic indicators presents a fuller picture of the UK economy

- Input producer prices continue to reflect exchange rate changes and world prices for crude oil

- Property mortgage transaction volumes fell sharply in 2007 and 2008 reflecting credit conditions

- Authors

1. Main points

The 12-month growth rate of the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) was 2.2% in November 2018, unchanged from October 2018.

The input Producer Price Index (input PPI) grew by 5.6% in the 12 months to November 2018, slowing from 10.3% in the 12 months to October 2018.

The output Producer Price Index (output PPI) grew by 3.1% in the 12 months to November 2018, down from 3.3% in the 12 months to October 2018.

The historical series shows the 12-month growth rate of CPIH peaked at 9.2% between September and December 1990 following sustained economic growth and rapid house price growth in the late 1980s.

Trends in input PPI continue to reflect exchange rate changes and world prices for crude oil.

Property mortgage transaction volumes fell sharply in 2007 and 2008 reflecting tightening credit conditions, and have yet to recover to their 2006 volumes.

2. Statistician’s comment

Commenting on today’s inflation figures, Head of Inflation Mike Hardie said:

“Inflation was little changed as falling petrol prices, thanks to a substantial drop in the cost of crude oil, were offset by rises in tobacco prices following the duty changes announced in the Budget.

“House price growth continued to slow with the smallest annual rise seen in over five years, led by price falls across London.”

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Summary

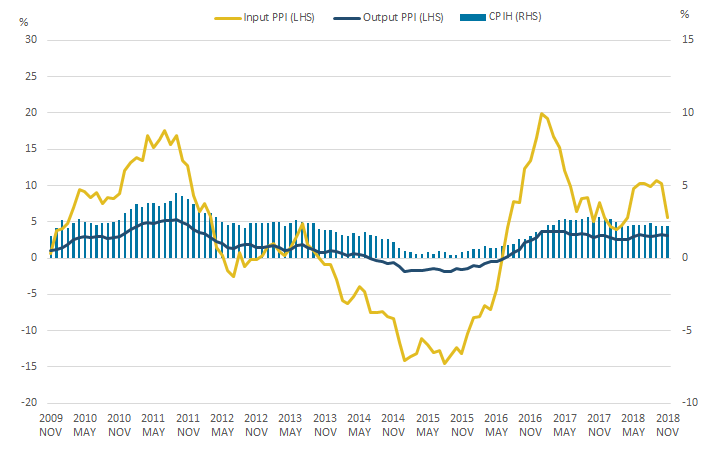

Figure 1 shows that the 12-month growth rate of the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) was 2.2% in November 2018, unchanged from October 2018.

The largest downward contributions to change in the 12-month rate came from falls in petrol prices and across a variety of recreational and cultural goods and services, principally games, toys and hobbies, and cultural services. These downward effects were offset by increased tobacco prices and, to a lesser extent, price rises in a variety of other categories, for example, accommodation services and passenger sea transport.

The input Producer Price Index (input PPI) grew by 5.6% in the 12 months to November 2018, slowing from 10.3% in the 12 months to October 2018. All product groups made a negative contribution to the fall in the annual rate, excluding other imported materials with a positive contribution of 0.02 percentage points. Crude oil provided the largest downward contribution of 3.86 percentage points.

The output Producer Price Index (output PPI) grew by 3.1% in the 12 months to November 2018, down from 3.3% in the 12 months to October 2018. The largest downward contribution to the decrease in the annual rate came from petroleum products, with a negative contribution of 0.28 percentage points.

Figure 1: 12-month growth rates for input Producer Price Index (PPI) (left-hand side), output PPI (left-hand side), and Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers' housing costs (CPIH) (right-hand side)

UK, November 2009 to November 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 1: 12-month growth rates for input Producer Price Index (PPI) (left-hand side), output PPI (left-hand side), and Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers' housing costs (CPIH) (right-hand side)

.png (26.0 kB) .xlsx (22.1 kB)Notes:

- These data are also available within the Dashboard: Understanding the UK economy.

4. The CPIH historical series provides long-term insight into price trends

Last week (14 December 2018), Office for National Statistics (ONS) published a historical series of our lead measure of inflation, the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers' housing costs (CPIH), which extends the series back to 1988.

CPIH has previously been calculated back to 2005, which is the earliest year that suitable data sources are available for constructing a rental equivalence index. The CPIH historical series was produced using a modelled rental equivalence price index for 1988 to 2004. These data are classified as official statistics, which form part of a longer series for the CPIH, of which the latter part, from 2005 onwards, constitutes a National Statistic. However, there are limitations with constructing a historical series and, as such, caution should be applied when interpreting the estimates.

The historical series shows the 12-month growth rate of CPIH peaked at 9.2% between September and December 1990 following sustained economic growth and rapid house price growth in the late 1980s. The contributions to CPIH offer further insight into price trends. Figure 2 shows the contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH for January 1989 to December 2004. Figure 3 shows the contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH for January 2005 to November 2018.

Figure 2: Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH (historical series)

UK, January 1989 to December 2004

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Contributions may not sum due to rounding.

- The “other” component includes: alcoholic beverages and tobacco; furniture, household equipment and maintenance; health; communication; restaurants and hotels; and miscellaneous goods and services.

Download this chart Figure 2: Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH (historical series)

Image .csv .xlsDuring the economic downturn of the early 1990s, all categories of goods and services contributed positively to the 12-month CPIH growth rate. Sterling was depreciating in the months after the economic downturn. This meant that relatively import-intensive categories of goods and services (including food and non-alcoholic beverages, and energy items) contributed more to the CPIH rate over this period since depreciation of the pound sterling tends to raise the cost of imports.

Generally, until the late 1990s the largest contribution (excluding the “other” category, which combines components) to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH was from owner occupiers’ housing costs, peaking at 2.35 percentage points in December 1990. During the latter years presented in Figure 2, the largest contribution came from housing costs including water, gas, electricity and other fuels, and excluding the owner occupiers’ housing costs component. Within this component, the largest increase in prices between 1998 to 2005 was water supply, which increased by 228.1%. The smallest price increase was seen by materials for maintenance and repair, which increased by 39.3% over the same period.

Figure 3: Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH

UK, January 2005 to November 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Contributions may not sum due to rounding.

- The “other” component includes: alcoholic beverages and tobacco; furniture, household equipment and maintenance; health; communication; restaurants and hotels; and miscellaneous goods and services.

Download this chart Figure 3: Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH

Image .csv .xlsFigure 3 shows the 12-month growth rate of CPIH has remained positive over the period, reaching its lowest point of 0.2% in September 2015 and peak of 4.8% in September 2008.

A range of factors impact the 12-month growth rate of CPIH including changes to the inverted sterling effective exchange rate. Components with higher import intensity (including energy prices which contribute to the transport, and housing, water, gas, electricity and other fuels components) have particularly reflected exchange rate changes. There is a possible lagged effect as exchange rate changes take time to feed through into renewed contracts. Additionally, changes in world commodity prices and domestic pressures also exert considerable influence on the consumer price of energy. For example, the price of Brent crude oil in pounds sterling, which is a relatively volatile series, influences trends in the fuels and lubricants component of CPIH. Recently, changes in the US dollar price of crude oil has also driven price changes in the energy components.

Changes in the contribution made by food and non-alcoholic beverages are broadly reflective of changes in the exchange rate over the period. As food and non-alcoholic beverage prices are relatively import intensive – at least 25% of the price of each component of food and non-alcoholic beverages is accounted for by either direct or indirect imports – they can be quite responsive to movements in the exchange rate.

Similar to the historical series, owner occupiers’ housing costs and housing, water, gas, electricity and other fuels were amongst the largest contributors to the 12-month growth rate of CPIH. Owner occupiers’ housing costs increased by 25% between January 2005 and November 2018.

Transport has been volatile in the period since January 2006, peaking at a positive contribution of 1.35 percentage points in March 2010 and a negative contribution of 0.35 percentage points in January 2015. Since December 2016, transport has generally remained the largest contributor, peaking during the period at 0.80 percentage points in February 2017. Transport services includes passenger transport by railway, road, air, and sea and inland waterway, all of which use fuels as an input and therefore face costs that vary with world prices for crude oil. This may account for the increased contribution from transport services from late 2016. Large movements in the contributions from transport services in March and April of each year reflect the change in the timing of Easter and its effects on air fares.

The contribution from education significantly increased in October 2012 after the changes to tuition fees were cleared by Parliament following the vote by peers in the House of Lords in 2010. In October 2012, education contributed 0.30 percentage points to CPIH compared with the previous month where it contributed 0.05 percentage points. The price index for the education component of CPIH increased by 186.9% between January 2005 and November 2018.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Presenting the historical CPIH alongside macroeconomic indicators presents a fuller picture of the UK economy

Figure 4 shows quarter-on-previous year’s quarter growth rate, for example, the growth from Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 1988 to Quarter 1 1989 for gross domestic product and the 12-month growth rate for CPIH for Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 1989 to Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2004.

Figure 4: Quarter-on-previous year’s quarter growth rate of GDP and 12-month growth rate of CPIH

UK, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 1989 to Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2004

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: Quarter-on-previous year’s quarter growth rate of GDP and 12-month growth rate of CPIH

Image .csv .xlsGDP is the value of all goods and services produced in the economy. The extent to which GDP growth creates inflationary pressures in the economy depends on how close the economy is to operating at full capacity. For an economy operating close to full capacity, increases in GDP are more likely to lead to increases in the wages offered by firms. This is due to the reduced pool of unemployed workers in the labour market that firms can draw from. The higher wages offered by firms result in “cost-push” inflation, as firms pass on the increased labour costs to consumers as higher prices of goods and services. Individuals have more money to spend due to increased wages, resulting in “demand-pull” inflation where aggregate demand expands faster than aggregate supply. These factors create inflationary pressures, though there may be a lag as the effect of economic growth on wages takes time to affect prices.

Figure 4 shows GDP quarter-on-previous year’s quarter growth began to decline from Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 1989, turning negative in Quarter 4 1990 at negative 0.2% growth. This coincided with the peak in 12-month growth rate of CPIH (9.2%). Quarter 4 1990 also marked the start of the economic downturn as quarterly growth rates remained negative for the second consecutive quarter. Negative quarter-on-previous year’s quarter GDP growth continued until Quarter 2 1992, negatively peaking at negative 1.8% in Quarter 2 1991. During the same quarter, 12-month CPIH growth was relatively high at 7.7%. As the economy emerged from the economic downturn, CPIH continued to steadily decline. After the recession, there were three peaks in quarter-on-previous year’s quarter GDP growth: 4.3% in Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 1994, then 4.5% in Quarter 2 1997 and 4.7% in Quarter 2 2000. Modest 12-month growth in CPIH was experienced during these quarters.

The 12-month growth rate of CPIH can also be compared with the UK House Price Index (HPI). Figure 5 shows the 12-month growth rates from January 1989 to December 2004.

Figure 5: 12-month growth rate of CPIH and UK HPI

UK, January 1989 to December 2004

Source: Office for National Statistics, HM Land Registry

Download this chart Figure 5: 12-month growth rate of CPIH and UK HPI

Image .csv .xlsThe UK HPI captures changes in the value of residential properties including asset prices. CPIH measures consumption and so asset prices are excluded. UK HPI and CPIH therefore follow different trends over time, but both may be affected by specific events. For example, an economic downturn may reduce house prices but also reduces the cost of consuming those services, captured by the owner occupiers’ housing costs component of CPIH.

Figure 5 shows in January 1989, the 12-month growth rate in the UK HPI was highest at 30.2% for the period 1989 to 2004. The 12-month growth rate of the UK HPI fell to 2.9% in January 1990, before turning negative, to negative 1.6% in April 1990. The decline of CPIH from its peak in September to December 1990 coincided with sustained negative growth in the 12-month UK HPI growth rate until September 1993.

The base rate can also be compared with CPIH. The base rate is the interest rate on money held by commercial banks in the Bank of England.

The base rate is one of the main monetary policy levers used to control inflation in the UK, since commercial banks usually pass on changes in the base rate to customers. For instance, an increase in the base rate raises the cost of borrowing and increases the interest paid to customers for saving. This leads to changes in customers’ borrowing and savings behaviour and exerts downward pressure on inflation. These behavioural effects explain why the base rate can be used to control inflation.

Figure 6 shows the 12-month growth rate of CPIH and the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), and the base rate over the period.

Figure 6: 12-month growth rate of CPIH and CPI, and the base rate

UK, January 1989 to December 2004

Source: Office for National Statistics, Bank of England

Download this chart Figure 6: 12-month growth rate of CPIH and CPI, and the base rate

Image .csv .xlsFigure 6 shows a strong positive correlation between the base rate and CPIH and CPI; when CPIH or CPI is high the base rate tends to also be high. Following the price instability of the 1980s, the base rate peaked at 14.9% in October 1989. It remained at 14.9% for 12 months, whilst the UK continued to experience high inflation.

The base rate was not used exclusively for inflation targeting prior to September 1992. The government adopted a discretionary approach with the base rate being set to achieve the government’s overall economic objectives (including price stability). One month after the UK left the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, the UK government adopted inflation targeting in October 1992. The inflation target was set between 1% and 4% for the Retail Prices Index excluding mortgage interest payments (RPIX), later moving to a target of 1.5% or less as measured by the RPIX.

The Bank of England (BoE) was given operational independence over monetary policy in May 1997, with the decision coming into force in June 1998. The BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee was tasked with setting the base rate such that the government’s target inflation rate of 2.5% RPIX was achieved. This target then changed to 2% CPI in December 2003.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Input producer prices continue to reflect exchange rate changes and world prices for crude oil

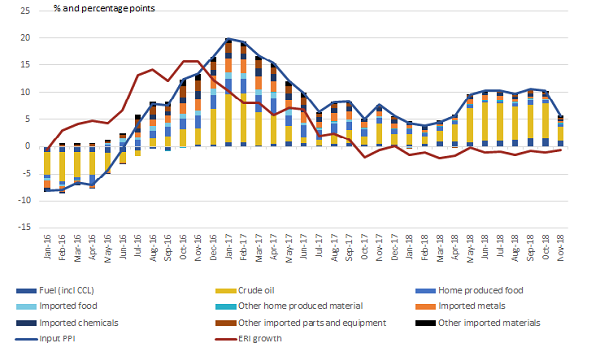

Figure 7 shows the contributions each of the components to the input Producer Price Index (PPI) have made to the 12-month growth rate, between January 2016 and November 2018. It also shows 12-month growth rates in the inverted sterling effective exchange rate (ERI) over the same period.

Figure 7: Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of input PPI and the inverted sterling effective exchange rate

UK, January 2016 to November 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics, Bank of England

Notes:

- Contributions may not sum due to rounding.

Download this image Figure 7: Contributions to the 12-month growth rate of input PPI and the inverted sterling effective exchange rate

.png (80.3 kB) .xlsx (22.2 kB)Since July 2016, input producer prices have been increasing on the year, peaking at a 12-month growth rate of 19.9% in January 2017. Since June 2017, the 12-month growth has ranged between around 5% to 10%. More recently, the 12-month growth rate in input PPI has fallen from 10.3% in October 2018 to 5.6% in November 2018. Figure 7 shows the growth rate trends to broadly follow the inverted sterling effective exchange rate.

Figure 7 shows the recent changes to the 12-month growth rate in input PPI are driven mainly by the contributions of crude oil to the headline rate. Whilst crude oil remained a large contributor, following the depreciation of sterling in the period following June 2016, all other imported components cumulatively have made a larger contribution to input PPI until August 2017. Crude oil contributions fell over much of the first half of 2017, reflecting a gradual strengthening of sterling and a decrease in world prices for Brent crude oil. The contribution has since increased and has remained the largest contributor to the 12-month growth rate of input PPI since August 2017, peaking at 6.99 percentage points in June 2018 and reflecting the gradual increases in crude oil prices (from $49.94 per barrel in August 2017 to $76.73 per barrel in October 2018).

Crude oil contributed 2.57 percentage points to the 12-month growth rate of input PPI in November 2018 compared with 6.38 percentage points in October 2018. The decline in the contribution reflects slower growth in the price of crude oil, which rose 15.5% on the year to November 2018, down from 40.4% in October 2018.

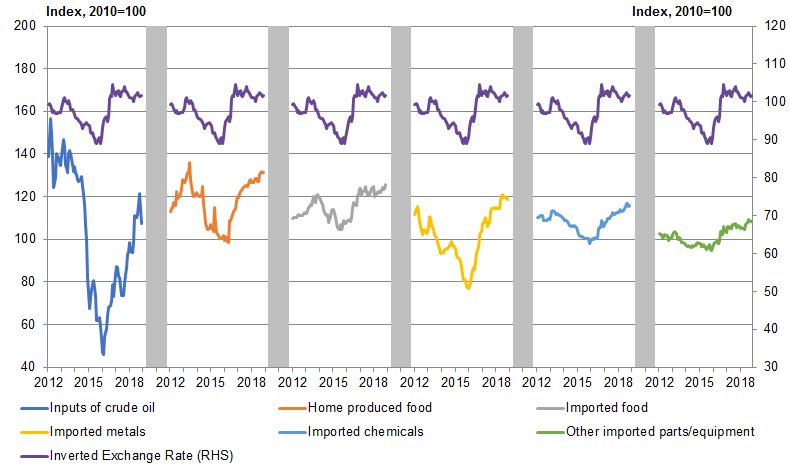

Figure 8 shows the relationship between crude oil and five other selected components of the input PPI and the inverted effective sterling exchange rate.

The price paths of the inputs, such as crude oil and imported metal, that are used to produce commodity-based manufacturing products have been trending more closely to changes in the exchange rate between January 2012 and November 2018 than prices of other imported parts and equipment. The UK input prices for these imported commodities reflect changes in both world prices and the exchange rate.

Figure 8: Inverted sterling effective exchange rate (right-hand side) and selected input Producer Price Indices (left-hand side) by product

UK, January 2012 to January 2018

Source: Office for National Statistics, Bank of England

Download this image Figure 8: Inverted sterling effective exchange rate (right-hand side) and selected input Producer Price Indices (left-hand side) by product

.png (36.0 kB) .xls (35.8 kB)Crude oil inputs appear to trend with the exchange rate less than imported metals and chemicals as the world price of crude oil is relatively volatile and therefore accounts for more of the change in input prices over the period. The 2016 to 2018 increases in the prices of Brent crude oil also reflect changes in the US dollar price feeding through into the sterling price. However, as imported inputs make up around two-thirds of the aggregate input PPI series, the exchange rate has a relatively strong influence on overall input PPI. The price of Brent crude oil decreased by nearly 20% between October 2018 and November 2018. This decrease was not reflected as strongly in the crude oil input PPI due to recent exchange rate effects.

Both food produced in the UK and imported food follow broadly changes in the exchange rate. This may reflect the nature of the food industry in the UK as food items can be fairly easily substituted between imports and domestic produce. There is also limited scope to expand or reduce quickly domestic supply to meet changes in demand in the short-term. Prices for food produced in the UK (specifically agricultural prices) may also reflect world prices as global competition means prices tend to follow similar trends.

The price paths of the inputs used in the manufacture of other parts and equipment, such as motor vehicles, trend less with movements in the sterling effective exchange rate compared with other input PPI series. The manufacture of these goods uses a wider range of intermediate inputs than needed to produce more commodity-based outputs. Overseas pricing strategy, competition and supply chain relationships, as well as the exchange rate, will therefore have a range of effects on input prices for these products and may mute the relationship between these series and the effective sterling exchange rate.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Property mortgage transaction volumes fell sharply in 2007 and 2008 reflecting credit conditions

Figure 9 uses mortgage transaction data from the Financial Conduct Authority to show mortgage transaction volumes for first-time buyers, former owner occupiers and re-mortgagers. The most recent quarterly data shown are for Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2018. Figure 9 also shows movements in property sales volumes between April 2005 and the most recent data; August 2018.

Figure 9: Mortgage and property transaction volumes

UK, April 2005 to August 2018

Source: Source: Financial Conduct Authority, HM Land Registry, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- Sales volumes are shown monthly. Quarterly mortgage transactions are averaged resulting in a monthly value which is shown for the first month of each quarter.

- Sales volumes do not equal the sum of the mortgage volumes. Sales volumes data include cash purchases and exclude remortgages. The Financial Conduct Authority also provide data on mortgages purchased by the council or by registered social landlord tenants exercising their right to buy, and purchased by those classified as “other” or “not known”. These groups are excluded from Figure 9.

Download this chart Figure 9: Mortgage and property transaction volumes

Image .csv .xlsTrends in mortgage transactions have moved broadly in line with those for property sales volumes over the period. Both property sales and mortgage transaction volumes fell sharply in 2007 and 2008, during the financial crisis. Property sales volumes fell by almost 80% from 152,000 in June 2007 to 33,000 in January 2009.

This decline in property transactions likely reflects the tightening of credit conditions (PDF, 2.9MB), which occurred during and immediately following the financial crisis. It may reflect a contraction in the supply of secured lending with some lenders leaving the market. Borrowers with higher loan to value requirements have faced the greatest tightening in credit conditions. But, lenders remaining in the market have also reduced the availability of secured lending to households with loan-to-value ratios below 75% (PDF, 2.9MB). Previous analysis showed a sharp reduction in the number of transactions having loan-to-value ratios greater than 90% in 2008.

Sales volume data from the UK House Price Index (UK HPI) are only available from 2012 for both mortgage and cash (including all properties purchased without a mortgage regardless of the payment method) transactions. Therefore, we cannot directly assess whether the 2008 to 2009 decline in property transactions affected cash and mortgage transactions equally. In the period since 2012, the proportion of cash purchases has remained relatively stable at around 30%.

Between July 2007 and January 2009, new mortgage transaction volumes fell by around 72% and property sales volumes fell by around 76%. Mortgage transaction volumes fell more for former owner occupiers (at 74%) than for first-time buyers (68%). This weakening in demand was reflected in the fall in house prices at the time, with average property prices falling by around 18% between their pre-downturn peak in September 2007 and their lowest point in March 2009. Former owner occupiers may be less inclined to move to a new property if they have lost equity in their existing property, while first-time buyers may try to take advantage of the improved affordability of properties.

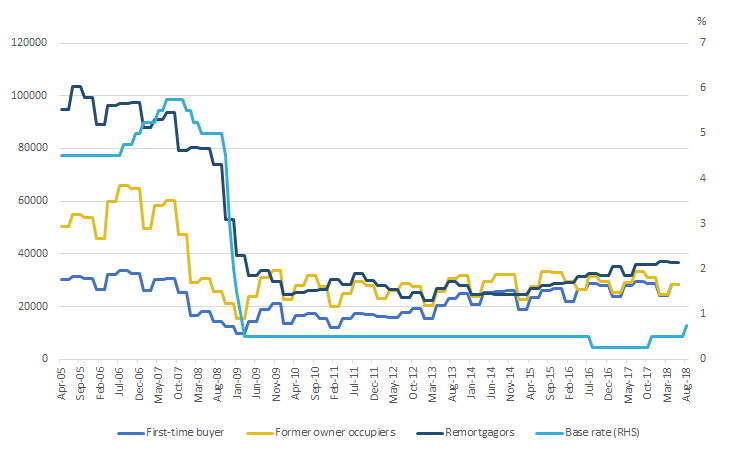

Figure 10 shows movements in transaction volumes for new mortgages for first-time buyers and former owner occupiers, and re-mortgage transaction volumes between April 2005 and August 2018. Movements in the Bank of England base rate are also shown.

Figure 10: Mortgage transaction volumes (left-hand side) and the Bank of England base rate (right-hand side)

UK, April 2005 to August 2018

Source: Financial Conduct Authority, Bank of England, HM land registry, Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- The chart shows the quarterly number of mortgage transactions averaged and repeated for each of the 3 months in the quarter.

Download this image Figure 10: Mortgage transaction volumes (left-hand side) and the Bank of England base rate (right-hand side)

.png (30.0 kB) .xlsx (21.0 kB)Mortgage transaction volumes and the Bank of England base rate fell sharply during the economic downturn. For new mortgages, this likely reflects market conditions and a similar fall in property sales. For re-mortgages, it may also be a reaction to movements in the Bank of England base rate. Although, changes in the base rate may not always be passed on as changes in the lending rates by lenders.

For existing home owners, when interest rates are high, re-mortgaging fairly regularly may appeal as a way to balance the cost of repayments and the predictability of monthly outgoings. A variable or tracker mortgage rate would risk sudden, possibly large, increases in mortgage payments as the base rate increased. Longer-term fixed rate mortgages would typically incur a higher mortgage rate to accommodate the risk of a base rate increase.

From March 2009 to July 2016, the base rate remained unchanged at 0.5%, which was 5.25 percentage points lower than its pre-downturn peak in July to November 2007. The low level of re-mortgages over this period may reflect consumers’ perceptions that the base rate was unlikely to change. Figure 11 shows the proportion of fixed rate mortgages generally increased between March 2009 and July 2016 with consumers opting for fixed rate mortgages on the lower base rate. The gradual increase in re-mortgage volumes from around 2015 may have reflected banks’ willingness to offer re-mortgage deals at lower interest rates, prompted by the lower base rate.

Following a reduction to 0.25% in August 2016, the base rate returned to 0.5% in November 2017 and rose again to 0.75% in August 2018. Figure 11 shows a continuation of the decline in the proportion of variable rate mortgages.

Figure 11: Mortgage transaction volumes by interest rate type

UK, Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2005 to Quarter 2 2018

Source: Financial Conduct Authority

Download this chart Figure 11: Mortgage transaction volumes by interest rate type

Image .csv .xlsFigure 11 shows in Quarter 2 2018, fixed rate mortgages covered around 95% of all mortgages, compared with around 46% in Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2010.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys