1. Main changes

Improvements for Blue Book 2023 include revisions to the measurement of a small number of multinational enterprises, reflecting a better measurement of their activities.

This work contributes to a better understanding and measurement of the impact of "globalisation" on the National Accounts and balance of payments.

Because of the small number of businesses involved so far there is no significant impact on total gross domestic product (GDP), however even at this early stage, these improvements have led to changes across a range of transactions and products that affect GDP, most noticeably on trade in goods and services.

2. Overview of globalisation in the context of the UK National Accounts

The scale and reach of international supply chains is nothing new. However, in recent decades globalisation has taken advantage of improvements in communications and transport, among others, to enable more complex relationships with greater impact. For the Office for National Statistics, this requires a greater understanding of the operations of multinational enterprises and trade across borders to ensure we continue to measure the National Accounts according to internationally agreed standards.

The purpose of this article is to describe the methods and guidance underpinning changes made to account for globalisation in Blue Book 2023.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Economic ownership

An important concept for understanding this work is the principle of economic ownership. It describes how we think of the ownership of goods and assets. Economic ownership belongs where the associated economic benefits and risks lie. In most cases, a change in economic ownership occurs at the same time as a change in legal ownership. However, some exceptions do apply, for example the economic and legal owner of leased assets may differ.

National Accounts guidance has responded relatively recently to this measurement challenge, for example around trade in goods. Previously, when goods crossed a boundary, a change of ownership was directly implied.

The United Nations System of National Accounts 2008 (SNA 2008) (PDF, 9,299KB) recognised complex supply chains required a more insightful view of ownership:

"A3.155 The 2008 SNA recommends that imports and exports should be recorded on a strict change of ownership basis.

"That is, flows of goods between the country owning the goods and the country providing the processing services should not be recorded as imports and exports of goods. Instead, the fee paid to the processing unit should be recorded as the import of processing services by the country owning the goods and an export of processing services by the country providing it."

This change, in principle, was also included in the International Monetary Fund Balance of Payments Manual version 6 (BPM6) (PDF, 3,038KB) and carried through, for example, to the European System of Accounts 2010 (ESA10) (PDF, 6,558 KB). Much of our work has been led by the United Nations Guide to Measuring Global Production 2015 (PDF, 5,215 KB).

The reporting of transactions when economic ownership changes follow company accounts reporting standards. This is because Financial Reporting Standard (FRS) 5, and subsequently 102, require accounts to reflect the substance of a transaction and not just the legal form of a transaction.

This is important for understanding the impact of increasingly complex global supply chains and geographic fragmentation of manufacturing. A UK-based entity can have economic ownership of goods located abroad, and similarly an overseas entity can have economic ownership in the UK.

Measuring transactions when economic ownership changes is particularly important for international trade. The primary data source for UK trade in goods estimates are HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) overseas trade in goods statistics (OTS), compiled from customs declaration data. Customs declaration data measure physical movements across the UK border effectively, and in most cases, this is correlated well with a change in economic ownership. However, there are circumstances where it will capture a physical import or export of goods but there is no change in economic ownership. There will also be cases where it will miss a transaction entirely if it does not cross a UK border.

Some existing high-level adjustments sourced from the International Trade in Services survey are applied to estimate the impact of economic ownership. However, our proof-of-concept work suggests these could be improved to ensure we fully account for changes in economic ownership. There is, however, currently no data source that fully captures economic ownership. Our work for annual National Accounts 2023 has focused on improving our measurement of changes in economic ownership at an individual business level, using company accounts as well as data and intelligence gathered by our Large Cases Unit (LCU).

The choice of businesses was based on knowledge from the LCU, where they were aware of globalisation issues, had a pre-existing relationship, and where the businesses were potentially significant to the UK economy. The input and co-operation of our chosen UK businesses has also been vital in developing our understanding and enabling us to make these changes.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Manufacturing models

Companies will employ a variety of models to enable them to manufacture goods. They may choose to manufacture in house, outsource manufacturing to a third party, or use a combination of both. Outsourcing to a third party could allow a manufacturer to save on cost and have access to capacity or a capability they do not have in house.

We take an interest when these types of manufacturing arrangements are outsourced and offshored, because it can lead to a difference in the treatment of goods that cross borders depending on its economic ownership.

The chosen manufacturing model also has implications for the industry an entity is classified to and their measurement.

We recognise that the exact nature of the contracts may not fit the stylized examples, but we will describe two cases and their treatment: factoryless goods production, and toll manufacturing.

Factoryless goods production

This is an arrangement where the directing business, or principal, outsources the entire production process to another business that acts as a contract manufacturer. This includes the purchase of raw materials by the contract manufacturer. The principal is described as a factoryless goods producer (FGP). The input of the principal is the intellectual property, blueprints, or designs of the product.

A principal acting as an FGP is seen as a merchant and should be classified to the wholesale industry because it is purchasing the completed goods with the intention to resell it. Manufacturing does not take place while the goods are under their economic ownership. The contract manufacturer will be classified to their relevant manufacturing industry according to the type of good.

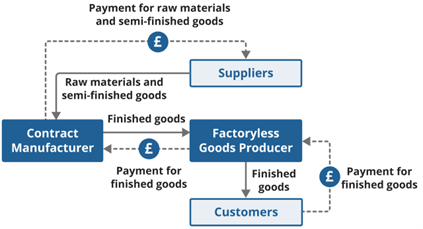

Figure 1: Example of a factoryless goods producer arrangement

Download this image Figure 1: Example of a factoryless goods producer arrangement

.png (35.3 kB)As an example of how this may work across borders, a UK-based FGP contracts an overseas contract manufacturer to manufacture a good according to their specifications. The contract manufacturer purchases all raw materials. The finished goods are purchased only by the FGP and sold in the UK and across the world.

When National Accounts and balance of payments transactions are measured at the point economic ownership changes occur, the following balance of payments transactions should be recorded:

goods purchased from the overseas contract manufacturer for sale in the UK should be considered an import to the UK from the country of the contract manufacturer

goods purchased from the overseas contract manufacturer for sale overseas should be a negative export with the country of the contract manufacturer, as they are considered goods under merchanting

the sale of goods overseas should be considered as an export of goods under merchanting from the UK to the country where the goods are sold

Most trade in goods transactions are recorded on a gross basis. Purchase of goods from overseas are recorded as imports and the sale of goods overseas are recorded as exports. However, goods under merchanting are recorded on a net basis. This means the purchase of goods are recorded as a negative export and the sale of goods are recorded as a positive export.

A more detailed explanation of goods under merchanting and its treatment is described in paragraphs 10.41 to 10.44 of the International Monetary Fund Balance of Payments Manual version 6 (BPM6) (PDF, 3,038KB).

The difference in price between the purchase and the sale earned by an FGP may be higher compared with a more traditional merchanting arrangement by a wholesaler. This is because the selling price may also include intangible contributions by the FGP, such as intellectual property.

In instances where this activity is large and the sale occurs in a different country to the location of the contract manufacturer, it can, at a detailed level, leave country by-product exports as a negative overall value. This is because the purchase (a negative export) is recorded with one country, and the sale (a positive export) is recorded with a different country.

Alternatively, where the contract manufacturer is based in the UK and the FGP overseas, the sale of the good from the contract manufacturer to the FGP should be captured as an export of goods from the UK to the country of the contract manufacturer. This happens regardless of the goods crossing the UK border.

Toll manufacturing

An alternative form of outsourcing to the FGP arrangement is toll manufacturing. In contrast to making use of a contract manufacturer, in this relationship the principal retains a greater level of control over the supply chain by providing all raw materials and components to a contracted toll manufacturer. The toll manufacturer supplies the plant, machinery, and labour to perform a manufacturing service on those materials.

The principal retains ownership of the raw materials, intellectual property, and finished goods throughout the process, while the toll manufacturer receives a service fee.

The principal in a toll manufacturing arrangement should be classified to the relevant manufacturing industry according to the type of good.

Companies using the toll manufacturing model may have different characteristics to traditional manufacturers, for example, low manufacturing employment. This means it may be difficult to identify them as manufacturers and can lead to them being misclassified to a service industry. One such example has been found as part of our proof-of-concept work.

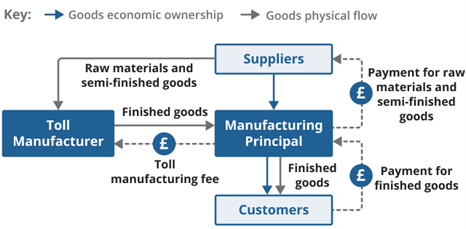

Figure 2 provides a visual example of a simple toll manufacturer model.

Figure 2: Example of a toll manufacturing arrangement

Download this image Figure 2: Example of a toll manufacturing arrangement

.png (42.1 kB)As an example of how this may work across borders, a UK-based manufacturing principal contracts an overseas toll manufacturer to carry out manufacturing services on their raw materials to produce a finished good. The finished goods are sold in the UK and across the world.

When National Accounts and balance of payments transactions are measured at the point economic ownership changes occur, the following balance of payments transactions should be recorded:

goods produced by the overseas toll manufacturer and sold outside the UK should be considered an export of goods from the UK to the country where the goods are sold

goods that return to the UK from the overseas toll manufacturer should not be considered an import of goods, as the goods are already under the economic ownership of the UK when it crosses the border

raw materials and semi-finished goods purchased outside the UK and used by the toll manufacturer as part of the production process should be considered an import of goods to the UK from the country the raw materials are purchased from

raw materials and semi-finished goods purchased in the UK and moved overseas to supply the overseas toll manufacturer as part of the production process should not be considered an export of goods

the service fee paid to the overseas toll manufacturer should be recorded as an import of services of the goods manufactured to the UK from the country of the toll manufacturer

Changing perspective, and considering a UK company as the toll manufacturer for a manufacturing principal based overseas:

goods manufactured by the UK toll manufacturer and sold in the UK should be considered an import of goods to the UK from the country of the overseas manufacturing principal

goods manufactured by the UK toll manufacturer and sold overseas should not be considered an export regardless of it crossing the UK border

raw materials and semi-finished goods purchased in the UK by the overseas manufacturing principal should be considered an export of goods from the UK to the country of the manufacturing principal, even if the goods physically remain within the UK

raw materials and semi-finished goods owned by the overseas manufacturing principal entering the UK should not be considered an import, because they remain under the ownership of the overseas manufacturing principal

the service fee paid to the UK toll manufacturer should be recorded as an export of services of the goods manufactured from the UK to the country of the overseas manufacturing principal

5. Intellectual property

It is through the control of intellectual property that businesses, and particularly multinational enterprises (MNEs), have the flexibility to choose their appropriate manufacturing model. Intellectual property (IP) refers to an original intangible creation, for example a story, invention, artistic work, or symbol. Ownership of intellectual property is protected by, for example, patents, copyright, and trademarks. These protections enable people and businesses to exploit their intellectual property for benefit.

Intellectual property, such as a patent, could be exploited by using it directly or licensing it out for production. If it is licensed out the owner should usually receive royalties in return. This could be to third party entities or to other companies within the same global group.

Of the IP held in the UK, some will be produced here through research & development or the creation of artists. Other intellectual property will be moved here because unlike physical assets, it is easy to move ownership of IP in to or out of a country. This means a MNE can centre their IP in one location as a global or regional hub. In such cases, it is likely there would be large international trade in services flows associated with this. Understanding how we capture payments associated with IP has been an important feature of our research and will continue to be explored in the future.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Future developments

A further article in September 2023 will provide more insight surrounding the improvements we have made. It will also outline our approach to product and industry reviews, as well as our strategic way forward on continuing to improve our estimation and understanding of the impact of globalisation.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Cite this article

Office for National Statistics (ONS), released 3 July Month 2023, ONS website, article, Globalisation in the context of the UK National Accounts: Blue Book 2023