1. Summary

This article sets out the sources and methods used to construct estimates of productivity in publicly funded education, most recently presented in Public service productivity estimates: total public service, UK: 2014.

It contains:

- a summary of the data sources used

- a breakdown of how we calculate estimates of productivity in education

- a description of recent methodological changes

- a discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of this approach

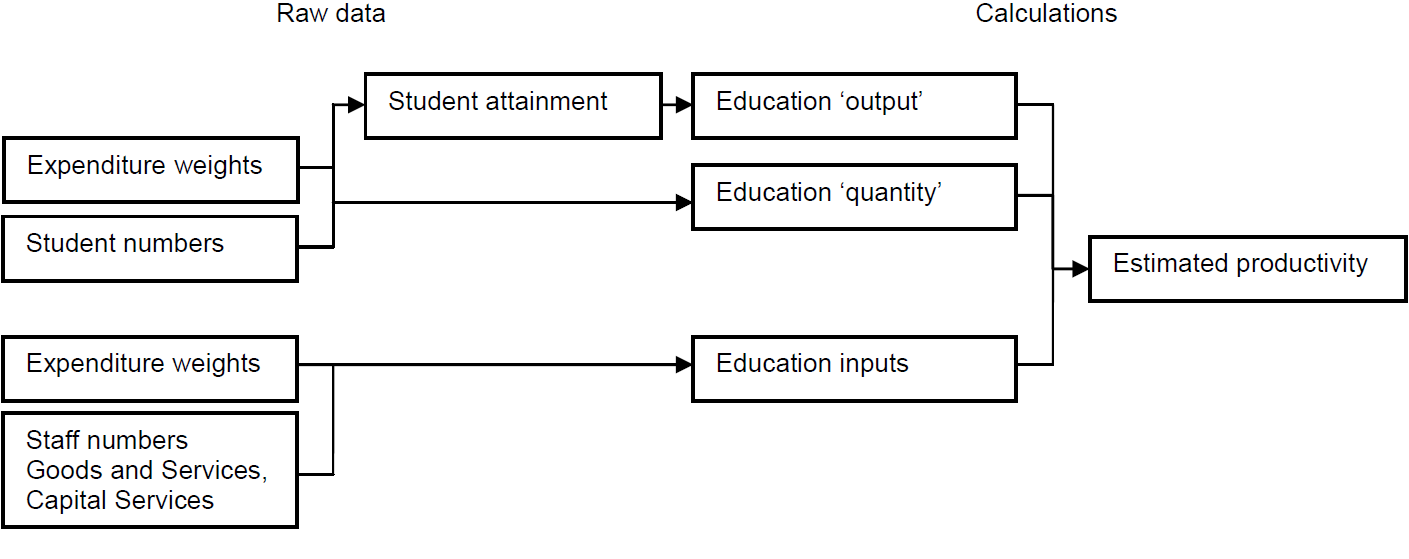

At the most aggregate level, our estimates of education productivity are based on the ratio of output to inputs. Adopting p, O and I to indicate productivity, output and inputs respectively, and including a subscript t for time-periods:

Estimates of the volume of education output are calculated using the number of students in several learning sectors. Data are gathered from central government and the devolved administrations for 8 different education sectors, including schools, the Higher Education training of teachers and health professionals and Further Education. Changes in the number of students in each sector are adjusted for absence and quality, weighted by their share in aggregate education expenditure and converted into a single volume of education output series.

Estimates of the volume of education inputs are calculated using data on education expenditure and direct measures of school inputs. Data are gathered on:

- labour input

- goods and services purchased by central and local government

- capital services

As with education output, an aggregate index of inputs is produced by weighting the growth of each component by their respective share in aggregate education expenditure.

The methodology for calculating aggregate education inputs, output and productivity involves several stages. An overview of the process is provided in Figure 1.

This note focuses on measuring productivity in publicly funded education. As a consequence, non-state funded schools and Higher Education, other than the training of teachers and some health professionals, are excluded from our estimates.

Figure 1: Overview of production process

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 1: Overview of production process

.png (34.7 kB)2. Education output

We publish 2 estimates of publicly-funded education delivered in the UK from 1997 onwards, on an annual basis. The first of these, quantity output, reflects changes in the numbers of students, attendance and their respective shares in aggregate expenditure. The second, quality-adjusted output, adjusts the quantity series for changes in the level of attainment. Both measures use data on student numbers and expenditure in 8 education sectors across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland to create chained volume estimates of education delivered.

The 8 sectors are all publicly-funded and comprise:

- pre-schools

- publicly funded Private, Voluntary and Independent (PVI) pre-school places

- primary schools including academies

- secondary schools including academies and city technology colleges

- special schools

- Further Education (FE)

- Higher Education training of teachers (Initial Teacher Training (ITT))

- Higher Education training of health professionals

The coverage of education estimates in the Public service productivity estimates: total public service, UK: 2014 broadly follows the treatment of education within the National Accounts methodological framework. The primary difference in coverage arises from the separate inclusion of Further Education (FE). These productivity estimates include FE as a stand-alone sector and includes all adult FE which is publicly funded.

The measure of education quantity is calculated using data on student numbers and expenditure in each of the 8 learning sectors listed above. Table 1 provides information about the sources of these data. Further information is available in the statement of administrative data sources.

Table 1: Sources of education output data: 1997 to 2014

| England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | ||

| Schools | Students | DfE | WG | SG | DENI |

| Expenditure | DfE | WG | SG | - | |

| Attainment | DfE | WG | SG | - | |

| Initial Teacher Training | Students | DfE | WG | SFC | DELNI |

| Expenditure | DfE | WG | SFC | DELNI | |

| Health Professional Training | Students | DH | WG | SG | DoHNI |

| Expenditure | DH | WG | SG | DoHNI | |

| Further Education | Students | SFA/BIS | WG | SFC | Department for the economy |

| Expenditure | EFA | WG | SFC | - | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

| 1. DfE: Department for Education, DH: Department of Health, SFA/BIS: Skills Funding Agency/Department formerly known as Business, Innovation and Skills, EFA: Education Funding Agency | |||||

| WG: Welsh Government | |||||

| SG: Scottish Government, SFC: Scottish Funding Council | |||||

| DENI: Department of Education Northern Ireland, DELNI: Department for Employment and Learning Northern Ireland, DoHNI: Department of Health Northern Ireland | |||||

| 2. Student data are provided on an academic year basis, while expenditure data are provided on a financial year basis. Data in academic and financial years are converted to calendar years by applying a cubic spline process. | |||||

Download this table Table 1: Sources of education output data: 1997 to 2014

.xls (27.6 kB)As government funded education is provided for free, it is considered a non-market output. The methodology used to produce estimates of non-market output is governed by ESA (2010), SNA (2008) and is set out in Atkinson (2005). As there is no effective price index for education, a volume-based approach is used to estimate education quantity, the methodology for which can be broken into several steps:

Time series data for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland are compiled examining the number of students and the level of expenditure in each educational sector. Pupil numbers in primary, secondary and special schools is adjusted to account for student absence.

A chain-linked Laspeyres volume index of output is produced for each educational sector at a UK level such that:

where:

- i, j and t index educational sectors, geographical areas and time respectively

- li,t is a chain-linked Laspeyres index of education quantity

- ai,j,t is the number of students

- xi,j,t is the level of expenditure in current price terms

- output in the initial period, t=0, is set equal to 100

A UK-level, chain-linked Laspeyres volume index of education quantity is calculated using the individual sector indices and relative cost weights, such that:

where:

- i and t index educational sectors and time respectively

- Lt is a chain-linked aggregate UK Laspeyres index of education quantity

- li,t is a chain-linked Laspeyres index of education quantity

- xi,t is the level of expenditure in current price terms

- output in the initial period, t=0, is set equal to 100

The result of this process is a chain-linked, UK-level, Laspeyres index of education quantity. There are several equivalent methods of generating this result. In particular, this approach is equivalent to first calculating the indices for geographical areas and then aggregating over educational sectors. Appendix A demonstrates that this approach is also equivalent to a methodology which weights activity by unit costs.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Quality adjustment

Estimates of education quantity produced by chain-linked Laspeyres indices above reflect changes in the quantity of education delivered, but take no account of changes in the quality of education services provided. Following Atkinson (2005), we incorporate additional steps to explicitly account for changes in the quality of provision in estimates of education output1.

In Public service productivity estimates: total public service, UK: 2014, output in primary and secondary schools is adjusted using the average point score (APS) per student in GCSE level examinations which are normally taken during the student’s eleventh year of schooling. From 2008, Level 2 attainment (L2) is used for England instead of APS. The reason was the significant increase in APS between 2008 to 2009 and 2011 to 2012 that could partly be attributed to increases in the number of non-GCSE examinations taken because of changes in the type of examinations, which counted towards performance. Education output in Scotland – where the Standard exams are taken in place of GCSEs – is quality-adjusted using the APS associated with these examinations. Growing average point scores are deemed to reflect greater scholastic attainment arising from improvements in the quality of education delivered.

The delivered quantity of Initial Teacher Training (ITT) courses is also adjusted for quality. In this case, the proportion of students who achieve Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) each year is used as a quality indicator.

As exam performance varies across geographical areas, the quality-adjustment is applied to primary and secondary school output in each country separately. The APS at GCSE level up to 2008 and the L2 from 2008 for England as well as the APS at GCSE level for Wales are provided by the Department for Education and the Welsh government respectively. The APS associated with the standard exams in Scotland are provided by the Scottish government. For reasons of data comparability and availability, the level of education quantity in primary and secondary schools in Northern Ireland is quality-adjusted using the APS and the L2 of English schools. ITT quantity in each geographical area of the UK is adjusted using the QTS award rate for England, which is also provided by the Department for Education. Here the assumption is made that changes in quality in ITT in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland follows the trend in England.

Estimates of quality-adjusted output are produced in a similar manner to quantity measures of delivered education. As before, the process is carried out in several steps:

Time-series data are compiled using:

- the number of students

- the level of expenditure in each educational sector

- the APS and/or the L2 at GCSE level for England and Wales, the APS for standard examinations in Scotland and the ITT QTS award rate in England

The quality adjustment measures for schools and ITT are converted into indices such that:

where:

- APS refers to APS or Level 2 attainment depending on which quality-adjustment is used As before, qi,t=0=1

A chain-linked Laspeyres volume index of quality-adjusted output is produced for each educational sector such that:

where:

- i, j and t index educational sectors, geographical areas and time respectively

- li,tQ is a chain-linked Laspeyres index of quality-adjusted education output

- ai,j,t is the number of students

- qi,t is the level of quality achieved in delivery

- xi,j,t is the level of expenditure in current price terms

- output in the initial period, t=0, is set equal to 100

- for educational sectors which are not quality-adjusted, qi,t~=q~i,t-1~=q~i,t=0=1

As before, a UK-level, chain-linked Laspeyres volume index of quality-adjusted output is calculated using the individual sector indices and the relative cost weights, such that:

where:

- i and t index educational sectors and time respectively

- LtQ is a chain-linked, aggregate UK, Laspeyres index of quality-adjusted education output

- li,tQ is a chain-linked Laspeyres index of quality-adjusted education output

- xi,t is the level of expenditure in current price terms

- output in the initial period, t=0, is set equal to 100

Notes for Quality adjustment:

- See Atkinson (2005) for a summary of the conceptual arguments surrounding the quality adjustment of non-market services.

4. Education inputs

We publish estimates of publicly funded education inputs in the UK from 1997 onwards. The inputs index is an aggregate of labour, goods and services and capital, broken down by the accountable level of government as follows:

- local authority labour

- central government labour

- local authority goods and services

- central government goods and services

- capital services

Changes in these components are weighted together using their relative shares in total government expenditure on education, to form a chain-linked Laspeyres volume index. This is the same approach used to calculate the output series which is described in Section 2 above.

Table 2 provides information about the sources of data used in education estimates in the Public service productivity estimates: total public service, UK: 2014. Further information is available in the statement of administrative data sources.

Table 2: Sources of education inputs data: 1997 to 2014

| Description | Source | |

| School Staff Numbers | ||

| England | Department for Education | |

| Wales | Welsh Government | |

| Scotland | Scottish Government | |

| Northern Ireland (teaching staff only) | Department of Education Northern Ireland | |

| Teacher Hours & Earnings | ||

| England & Wales | Department for Education | |

| Scotland & Northern Ireland | ONS Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings | |

| Earnings data for school support staff | ONS Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings | |

| Labour, Goods & Services & Capital Expenditure | ||

| Local authority Labour expenditure | Expenditure: ONS National Accounts | |

| Deflator: ONS National Accounts | ||

| Central government Labour expenditure | Expenditure: ONS National Accounts | |

| Deflator: ONS Average Earnings Index (public sector/education) | ||

| Goods & Services expenditure incurred by Local Authorities | Expenditure: ONS National Accounts, | |

| Deflator: Derived from s251 LA expenditure summary (England) | ||

| Goods & Services expenditure incurred by Central government | Expenditure: ONS National Accounts | |

| Deflator: Composite derived from ONS National Accounts | ||

| Capital services | ONS Consumption of fixed capital | |

| Source: Office for National Statistics | ||

| Notes: | ||

| 1. LA: Local Authority | ||

| 2. Data in academic and financial years are converted to calendar years by applying a cubic spline process | ||

Download this table Table 2: Sources of education inputs data: 1997 to 2014

.xls (28.2 kB)Labour

The majority of labour input is measured directly using teacher and school support staff numbers disaggregated into occupational groups such as head teachers, classroom teachers and teaching assistants. Teacher numbers for England and Wales are also adjusted for actual hours worked. Teacher and support staff numbers are multiplied by average salaries to give implied total expenditure on school staff. Annual rates of growth in staff numbers (by occupational group) are weighted together using their relative shares in school staff expenditure, to form a chain-linked Laspeyres volume index. This is the same statistical technique as used for the output series (described in Section 2 above).

For each of the UK’s 4 countries, separate input indices are calculated for teaching and support staff. These are weighted together using their relative expenditure shares to give an overall schools labour index for each country. The UK schools labour index is then calculated by weighting together the 4 country indices using their relative shares in total UK school staff expenditure.

A small proportion of labour input is measured indirectly using deflated expenditure. This relates to administrative work carried out by staff in central government. A proportion of Further Education (FE) expenditure is also included, to represent FE labour input.

It is assumed that administrative labour input from local authorities moves in the same way as school staff input, as insufficient data are available to separately measure local authority administrative labour.

An overall UK labour input index is calculated by combining the direct and indirect components, using central and local government shares in employee-remuneration expenditure.

Goods and Services

Goods and services are measured indirectly using deflated expenditure; calculations are at a UK level. This expenditure comprises the following components:

- goods and services expenditure incurred by local authorities (for example, schools equipment, energy costs, pre-school education provided by the Private, Voluntary and Independent sector)

- goods and services expenditure incurred by central government (for example, office costs, Higher Education courses for health professionals, Initial Teacher Training)

- Further Education (local and central government procurement)

A composite Paasche deflator is calculated for both local and central government expenditure on goods and services using expenditure breakdowns from schools and central government and identifying appropriate deflators for each expenditure category.

An overall goods and services index is calculated by combining the above components, using central and local government shares in total goods and services expenditure.

Capital

Capital is measured using the ONS consumption of fixed capital series. This represents the flow of services provided by the capital stock within the education system each year, which primarily comprises buildings. Data for both central and local government capital is included. This is converted to an index to be aggregated to the total inputs index.

Total inputs

A chain-linked Laspeyres volume index of total inputs (across educational sectors and geographical areas) is calculated using the individual components and their relative cost weights, such that:

where:

- i and t index inputs components and time respectively

- Lt is a chain-linked aggregate UK Laspeyres index of education inputs

- fi,t is the volume of input by component

- xi,t is the level of expenditure in current price terms

- output in the initial period, t=0, is set equal to 100

5. Revisions to methodology

There has been 1 data source change since the Public Service Productivity Estimates: Education 2013. The ONS Volume Index of Capital Services (VICS), which used a 5-year moving average of the constant price, is no longer available and was replaced with the ONS consumption of fixed capital series.

Two methods changes were introduced in the Public Service Productivity Estimates: Education 2013 described in the Methods Changes in the Public Service Productivity: Education 2013 regarding the treatment of academies and the change of quality-adjustments for England from 2008.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Worked examples

To provide a sense of how education developments affect the calculation of inputs, output and productivity, we have produced a simplified spreadsheet model of the process. We have published this spreadsheet alongside this document; see Appendix B for worked examples. This spreadsheet includes information about a fictional education system in a country with 2 geographical areas (East and West), 2 educational sectors (Lower and Upper), and 2 inputs to production (labour and goods and services). As such, it retains many of the complexities of education estimates in the Public service productivity estimates: total public service, UK: 2014, while the reduced number of dimensions makes it more easily understood.

The objective of the worked example is to demonstrate how educational developments affect the calculation of productivity. Using the example allows the growth rates of key series to be changed, for example:

- the growth rates of student numbers (output)

- the growth rates of inputs

- the rate of change in student attainment (quality-adjustment)

The effect of changes can then be observed in the inputs, output and productivity estimates. Those who are interested in the more detailed calculation steps can also follow these using the included worksheets. This section introduces the example’s simplifying assumptions. The results of 3 customised scenarios devised using the accompanying spreadsheet are described in Appendix B.

At the most aggregate level, changes to inputs and output have a largely predictable impact on productivity; if inputs rise without a corresponding increase in output, productivity declines. If output increases without a corresponding rise in inputs, productivity goes up. However, the precise impact of a specific change for example, a 10% increase in the number of teachers, depends on the input mix and the relative size of different educational sectors in different parts of the country. Changes which affect higher weighted inputs, in larger educational sectors will have a greater impact on overall productivity than changes affecting lesser weighted inputs, in relatively small educational sectors.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys7. Stakeholder needs

We actively seek feedback from stakeholders of our public service productivity statistics in order to inform its future work priorities. We are particularly interested in views on the value of these statistics to inform policy debates and research projects. The Quality and Methodology Information (QMI) for the total productivity article 2014 includes a section on stakeholder needs and perceptions.

In addition, we have produced a document containing a series of frequently asked questions that provides stakeholders with a short explanation of the key concepts relating to public service productivity estimates: frequently asked questions, including how they relate to other issues such as “efficiency” and “value for money”. This document also provides an overview of methods used to create the statistics and guidance on how they should be used.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys8. Strengths and limitations

The approach adopted by education estimates in the Public service productivity estimates: total public service, UK: 2014 is designed to provide accurate, consistent and timely estimates of productivity in publicly funded education in the UK. It covers activity in 8 educational sectors. However, there are several areas which are the subject of continuing improvement efforts. These can be categorised as data issues, methods of quality-adjustment, institutional differences and timing. The following sections briefly review each of these areas.

Data issues

One of the challenges of producing the statistics is the production of estimates of education inputs and output which are comparable across countries, sectors and through time. This represents a significant data processing challenge, as the relevant series are published at different times of year, on different annual bases and often measure significantly different quantities across countries. Additional complexities arise from shifts in policy or educational innovations, as the existing published series may be modified to reflect new priorities.

We adopt a range of policies designed to ensure the comparability of the data series through time. Firstly, data are requested directly from the Department for Education and the devolved administrations in a format which ensures that both the most recent data and any revisions are included in the final estimates. Secondly, the data request is designed to match, as closely as possible, across geographical areas. Thirdly, where a complete time-series is not available, or where the coverage of an established indicator has been changed, we make a set of assumptions designed to estimate the missing data.

Methods of quality adjustment

The quality adjustments applied to education output in education estimates in the Public service productivity estimates: total public service, UK: 2014 are based on the Average Point Score (APS) or Level 2 attainment (L2) of students in exams at the end of their eleventh year of schooling, and the proportion of students on Initial Teacher Training (ITT) courses who attain Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) each year.

The behaviour of the quality-adjustment based on the APS attained by students in GCSE and equivalent examinations has changed as the coverage of this indicator has evolved over time. The Wolf Report (2011), for example, presents evidence on the impact of vocational qualifications on school performance measures in England. As a result, the Department for Education announced significant reforms to the classification of examinations and school performance measures which took effect in 2014. In 2015, when we published the 2013 productivity estimates, we replaced APS data in England with L2 data for years 2008 to 2013 to reflect this change. This is the current method used for quality-adjustment in England.

To further address this and other data issues, we have undertaken to review alternative methods of quality adjustment, with a view to generating a new method of accounting for changes in the standards of delivered education in the UK.

Institutional differences

Alongside issues arising from missing data or from conceptual problems of quality-adjustment, there are a small number of problems which arise from differing education policies and data collection across different jurisdictions within the UK. Of these, the most high-profile concerns differences in examination systems at the end of school year 11, between students in Scotland and students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

While students in the rest of the UK sit GCSE or equivalent examinations at the end of their eleventh year of school, in Scotland students sit “Standard Grade” examinations. The 2 systems differ both in terms of the tariff points awarded to students who achieve at different levels and in terms of the trend in average point scores through time. Specifically, while English average point scores have risen steadily between 2005 and 2010; students in the Scottish system have seen a much slower rate of increase.

Differences in institutional arrangements between jurisdictions represent a significant issue for comparability across geographical areas of the UK. The impact of these differences in the future depends on the extent of policy reforms in the devolved administrations. We are monitoring these developments.

Timing

The timing of data releases on student and teacher numbers and education expenditure represents a constraint to both more frequent and timelier publications of productivity in publicly-funded education. We will keep the timeliness of the productivity articles under review in consultation with stakeholders.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys