1. Main points

New estimates of labour productivity suggest that changes in the aggregate mix of activity in the UK economy – as well as lower productivity growth in telecommunications, manufacturing and finance industries – account for a large proportion of the UK’s recent productivity slowdown.1

New estimates of regional labour productivity suggest wide differences across the UK: the five sub-regions of London made up the top five areas by labour productivity, while predominantly rural areas in England and Wales had among the lowest levels of labour productivity in 2016.

The volume index of capital services for the UK market sector grew by 1.9% in 2016 – little changed on 2014 and 2015, but lower than in the decade leading up to the economic downturn.

Experimental estimates indicate that current price investment in intangible assets was £134.2 billion in 2015, compared with £141.7 billion for investment in tangible assets over the same period; this is the first time since 2000 that investment in tangible assets has been higher than investment in intangible assets.

An international review of best practice in the production of productivity statistics published as part of this bulletin suggests that ONS’ performance is comparable with other national statistical institutes, but this varies depending on the measure; the report provides important insights to shape the next stage of our development programme and suggests that our current plans will make ONS a relatively strong performer in this group.

Note for: Main points

- Recent research by ONS has identified that there is scope for improvement to the telecommunications producer price deflator used in the output measure. If implemented, it appears likely this would increase the output and productivity of the telecommunications sector. However, as telecommunications are inputs into other industries, there are likely to be equal and offsetting falls in output and productivity across a number of other sectors that used this service as an intermediate input. This change may therefore affect the performance of telecommunications compared with the other sectors, whilst leaving the overall aggregate productivity picture broadly unaffected.

2. Detailed industry estimates of labour productivity

As part of our ongoing development programme, we have been working to extend the range and detail of the labour productivity statistics that we publish. In April 2017, we published the first estimates of quarterly regional labour input consistent with the UK’s headline labour productivity metrics. In July 2017, we published experimental labour productivity data at a more detailed level of industrial granularity for the 2009 to 2017 period, as well as the first industry-by-region labour productivity metrics for the UK consistent with headline data. In October 2017, we published updated estimates of the UK’s labour productivity performance relative to the other G7 economies, as well as the first data on international comparisons of labour productivity by industry.

These developments have provided significantly more information to enable users and policy-makers to better understand recent trends in UK labour productivity growth and this release continues this run of new developments. In particular, in this release we have extended the time series of our detailed-industry labour productivity dataset back to 1997. These data include labour productivity data for 66 different industry groupings and for around 50 “division” level industries from the Standard Industrial Classification 2007: SIC 2007, presenting a much more detailed picture of productivity over the past 20 years than was previously available.

The main development that has enabled the publication of these longer time series at a more detailed industrial level concerns the treatment of data at and around the change in the industrial classification – from SIC 1992 to SIC 2007 – which took place between 2008 and 2009. Changes in industrial classifications are critical if economic statistics are to track economic and technological developments in the economy: capturing new activities as they emerge in distinct categories, increasing the level of detail available for maturing industries and, where necessary, grouping activities that are shrinking as a proportion of the UK economy. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) follows international best practice in this regard, ensuring that the different datasets that we produce are internationally comparable.

However, changes in the industrial classification can create challenges for production of coherent, detailed, historical time series of data. In particular, the Labour Force Survey data that feed into the calculation of labour productivity were based on SIC 1992, before switching to SIC 2007 from 2009 onwards. To deliver a single, coherent labour productivity dataset for the full time series, our current system uses a simple “one-to-one” mapping to convert historical data to the new industrial classification. While this is sufficient for a high level of industry aggregation, a more detailed method was needed to produce a historical set of data at the 66 industry level. To address this, a proportional mapping methodology has been developed and implemented for the experimental lower-level series. The methodology for our higher-level National Statistics has been left unchanged. More detail on this change is available in the companion article published alongside this release, but it considerably improves the time series quality of low-level industry labour inputs.

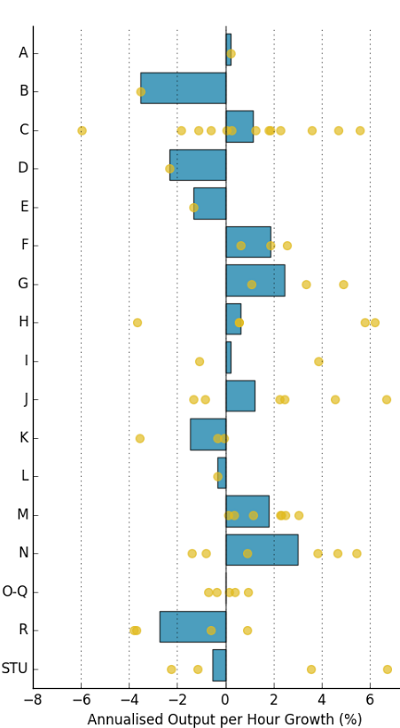

The importance of this finer industry detail is highlighted in Figure 1, which shows that even over long periods, productivity growth can differ substantially within industry groupings. Figure 1 shows the annualised compound average growth rates of labour productivity between Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2009 and Quarter 1 2017, for both industry sections (an aggregated industry breakdown – the bars), and the lower, division-level components of those industries (the points). In some industries – for example, construction (F) – the labour productivity growth of the components is similar to that of the division as a whole. However, for a majority – including manufacturing (C), transportation and storage (H), telecommunications (J), and administrative and support services (N) – the section level growth rate reflects a mixture of very different performances at the lower level.

Figure 1: Annualised output per hour growth per industry

UK, seasonally adjusted, Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2009 to Quarter 3 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- A: Agriculture, forestry and fishing; B: Mining and quarrying; C: Manufacturing; D: Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; E: Water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities; F: Construction; G: Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; H: Transportation and storage; I: Accommodation and food service activities; J: Information and communication; K: Financial and insurance activities; L: Real estate activities; M: Professional, scientific and technical activities; N: Administrative and support service activities; O-Q: Public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities; R: Arts, entertainment and recreation; and STU: Other service activities; activities of household and extra-territorial organisations and bodies.

Download this image Figure 1: Annualised output per hour growth per industry

.png (67.8 kB) .xls (26.6 kB)As a result of this work, it is now possible to produce a more granular picture of which industries are driving the slowdown in productivity growth since the economic downturn. As set out previously, growth in whole economy labour productivity can be decomposed into contributions from each industry – reflecting the effect that productivity growth within an industry has on the UK’s aggregate performance – as well as an allocation effect. This allocation effect captures changes in the mix of different industries in the UK economy overall, in terms of both shares in value added and shares of labour input. For instance, if the share of labour input used by a low-productivity (high-productivity) industry increases through time at the expense of high-productivity (low-productivity) industries, then the UK’s aggregate performance will weaken (strengthen), independent of the growth rates of productivity within specific industries. In other words, productivity in each individual industry could increase, but overall productivity could still fall if sufficient labour moved from higher to lower productivity industries.

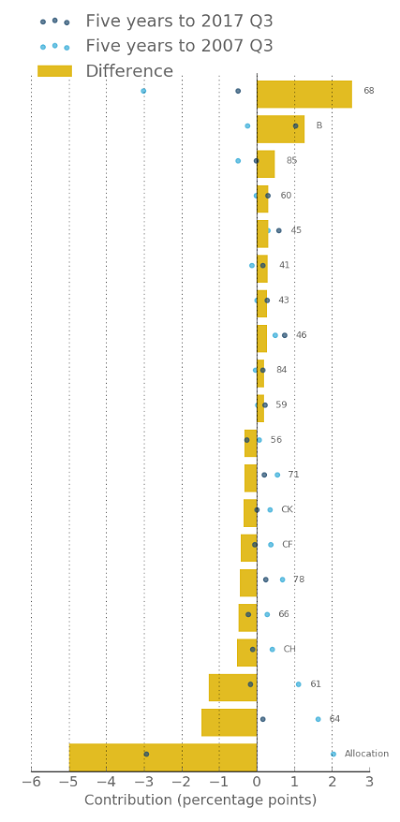

By comparing the contributions to labour productivity growth of specific industries prior to the downturn with the equivalent contributions to growth following the downturn, the change in contributions can be used to help explain the slowdown of whole economy productivity growth. This is shown in Figure 2, which uses the new, longer time series of labour productivity to compare contributions to growth in the five years to Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2007 (the light points) with contributions to growth in the five years to Quarter 3 2017 (the dark points). The differences between these points are shown as bars and these represent the change in the contribution of each industry to aggregate labour productivity growth over this period. Industries are ordered from those whose contribution increased the most, to those whose contribution was most reduced. The same is also done for the allocation effect. To highlight the important results, only the top 10 and bottom 10 contributors are shown.

Figure 2: Contribution to whole economy output per hour growth, 10 highest and 10 lowest contributors

UK, seasonally adjusted, five years to Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2007 and five years to Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- 68: Real estate activities; B: Mining and quarrying; 85: Education; 60: Programming and broadcasting activities; 45: Wholesale and retail trade and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; 41: Construction of buildings; 43: Specialised construction activities; 46: Wholesale trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles; 84: Public administration and defence; compulsory social security; 59: Motion picture, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing activities; 56: Food and beverage service activities; 71: Architectural and engineering activities; technical testing and analysis; CK: Manufacture of machinery and equipment n.e.c.; CF: Manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations; 78: Employment activities; 66: Activities auxiliary to financial services and insurance activities; CH: Manufacture of basic metals and metal products; 61: Telecommunications; and 64: Financial service activities, except insurance and pension funding.

Download this image Figure 2: Contribution to whole economy output per hour growth, 10 highest and 10 lowest contributors

.png (69.4 kB) .xls (20.5 kB)This analysis highlights a number of important results. Firstly, at this level of detail1, the allocation effect accounts for 5 percentage points of the 7.1 percentage points slowdown in productivity between the two periods. This means that changes in the mix of industries in which individuals are employed accounts for the largest proportion of the slowdown in growth in recent years. Rather than adding to labour productivity growth as it did over the five years to Quarter 3 2007, the allocation effect held back output per hour growth over this period. Secondly, the slowdown in measured productivity growth in several industries plays an important role in explaining the slowdown in the UK’s aggregate performance in recent years. In particular, the telecommunications2, finance, and manufacturing industries made considerable contributions over this period. Thirdly, despite the more recent period being characterised as the “productivity puzzle”, several industries made an enlarged contribution to aggregate productivity growth over this period. In particular, the stronger growth of labour productivity in real estate (which strengthened from an annual rate of output per hour growth of negative 4.8% between Quarter 3 2002 and Quarter 3 2007 to negative 0.7% per year between Quarter 3 2012 and Quarter 3 2017), and mining and quarrying (which strengthened from negative 2.7% to positive 9.4% over the same period) enabled these industries to make a more positive contribution to aggregate output per hour growth. This work highlights that trends at an aggregate level can mask a diverse array of experiences – which our development work aims to bring to light.

Notes for: Detailed industry estimates of labour productivity

Note that because they depend on movements between different industries, analyses of this kind are scale dependent: the larger the number of industries used, the larger the size of the allocation effect, as there are more categories for workers to “move between”. This explains the discrepancy in the size of the allocation effect for different levels of aggregation.

Recent research by ONS has identified that there is scope for improvement to the telecommunications producer price deflator used in the output measure. If implemented, it appears likely this would increase the output and productivity of the telecommunications sector. However, as telecommunications are inputs into other industries, there are likely to be equal and offsetting falls in output and productivity across a number of other sectors that used this service as an intermediate input. This change may therefore affect the performance of telecommunications compared with the other sectors, whilst leaving the overall aggregate productivity picture broadly unaffected.

3. Regional labour productivity

Alongside these new estimates of more detailed industry-level labour productivity, we are also publishing new, experimental estimates of labour productivity for NUTS1, NUTS2 and NUTS3 (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) sub-regions of the UK, selected UK city regions and English Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs).

These estimates are based on a new, improved methodology for calculating regional economic output known as “balanced” regional gross value added (GVA(B)). This measure “balances” the income and production approaches to measuring the economy into a single estimate at a regional level and has been introduced to replace the previous method, which calculated regional GVA based on the income method alone.

These new data suggest that labour productivity varies widely across the UK. Figure 3 shows the NUTS2 sub-regions with the highest levels of labour productivity in 2016, indexed to the UK average. Inner London West had the highest level of labour productivity in 2016, some 46% above the UK average. The other four NUTS2 sub-regions of London are also shown in Figure 3, while the highest labour productivity level outside of London was in Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire (15% above the UK average). Just two NUTS2 sub-regions in Scotland and one in the north of England are represented: overall, 11 out of the 40 NUTS2 areas had labour productivity above the UK average.

Figure 3: Gross value added per hour worked – highest ranking UK NUTS2 sub-regions

Unsmoothed, current prices, 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 3: Gross value added per hour worked – highest ranking UK NUTS2 sub-regions

Image .csv .xlsBy contrast, no NUTS2 sub-regions in London or the South East are represented among the lowest-performers. Figure 4 shows the NUTS2 sub-regions with the lowest nominal labour productivity levels. Most of the places with the lowest productivity levels were relatively rural areas of the country, for example, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly, Lincolnshire, and West Wales and The Valleys, which supports the results of recent ONS analysis. The lowest productivity in a predominantly urban sub-region occurred in South Yorkshire.

Figure 4: Gross value added per hour worked – lowest ranking UK NUTS2 sub-regions

Unsmoothed, current prices, 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 4: Gross value added per hour worked – lowest ranking UK NUTS2 sub-regions

Image .csv .xlsSimilar data have also been calculated and published for the 168 NUTS3 sub-regions of England, Scotland and Wales. At this smaller geographical scale, the size of the differences between the highest and lowest sub-regional productivities is considerably larger, reflecting wider variation in the prevalence of different types of activity in different areas of the UK. In 2016, the sub-region with the highest labour productivity (Tower Hamlets, London) had a productivity level 2.6 times greater than the sub-region with the lowest labour productivity (Powys, Wales).

Alongside these current price estimates for 2016, we have also produced the first regional and sub-regional estimates of labour productivity in real terms. These estimates are experimental and have been derived for NUTS1 and NUTS2 areas using the new real GVA (B) data. The “real” GVA (B) data were produced by deflating the current price estimates for 112 industries using national industry deflators: these data consequently adjust nominal regional value added for national price trends in the output of industries present in each region. Ideally, we would use regional prices to deflate each industry rather than national deflators. However, while we are investigating the possibility of providing increased information on regional prices in the future, such data are not currently available. In their absence, this new methodology still represents a considerable step forward.

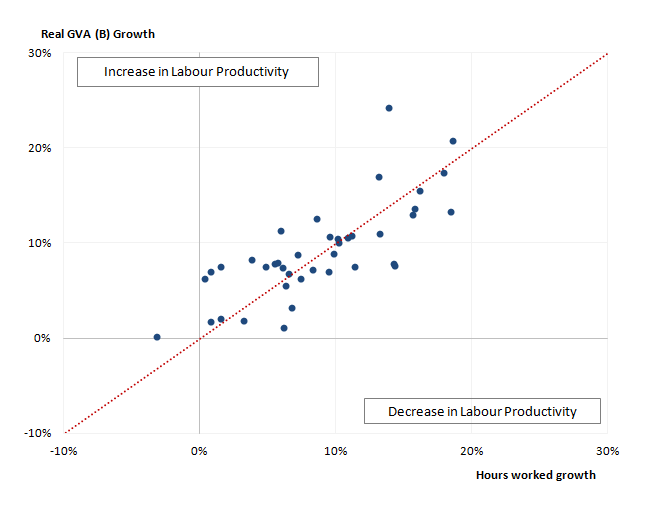

The main strength of these new, experimental data is that they can be used to show time series changes in regional labour productivity growth, which the previously published, nominal series could not. For example, Figure 5 plots total real GVA (B) growth against growth in total hours worked for the 40 NUTS2 sub-regions of the UK for the period 2011 to 2016. For sub-regions plotted above (below) the 45-degree line, real GVA growth is estimated to have been faster (slower) than the growth of total hours worked, and these sub-regions have consequently seen productivity rise (fall) over this period. Figure 5 indicates that only half of the sub-regions (20 out of 40) experienced real productivity growth over this period. For the remaining 20 areas, which include a majority of the English sub-regions, real productivity levels were lower in 2016 than in 2011.

Figure 5: Total growth in real gross value added compared with total growth in hours worked for NUTS2 sub-regions of the UK

2011 to 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this image Figure 5: Total growth in real gross value added compared with total growth in hours worked for NUTS2 sub-regions of the UK

.png (15.8 kB) .xls (101.4 kB)These differences in productivity growth over this period reflect quite marked differences in real GVA and labour input growth across sub-regions. For example, in Inner London West, GVA and hours worked grew by 21% and 19% respectively between 2011 and 2016, while in East Yorkshire and Northern Lincolnshire, GVA growth was zero while hours worked fell by 3% over the same period. These GVA and hours worked data show that very different economic pathways occurred in the two regions over this period, even though both ultimately resulted in very small changes in each area’s respective labour productivity levels over this period.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys4. Volume index of capital services

Increasing the depth of the labour productivity data that we publish has been an important focus of our development work, as has increasing the range and coverage of our data. As part of this release, we have published new, more detailed estimates of the volume index of capital services (VICS), which is an important factor in explaining the productivity performance of different industries.

In a conventional production function, firms combine factors of production – usually labour and capital – to deliver output. Labour input is usually measured in terms of hours worked, jobs or employment, while two measures of capital are in common use. The first is the capital stock, which measures the value of capital accumulated for production, including physical assets such as machinery, vehicles and buildings, and intangible assets such as software, and research and development. This measure of capital is a wealth measure – capturing the value of all the assets available for productive use. However, while the value of available assets for production is important, the preferred measure of capital input for production is capital services: the value that a given asset contributes to production each period. While the capital stock values a machine, for instance, at its resale value, capital services measure the value of the contribution of a machine to the productive process. Under certain assumptions, these services are equal in value to the rental that a firm would pay for the use of an equivalent asset for a given period. It is these capital services that firms combine with labour input to deliver output.

These experimental data have been developed considerably since their last release and indicate that the contribution of capital to production grew at similar rates in 2014, 2015 and 2016 – albeit lower than during the pre-downturn period. The current VICS estimates are compiled for the UK market sector, for 62 component industries (as compared with 10 industries previously) and for 13 asset categories. VICS are also now compiled quarterly rather than annually, up to and including Quarter 2 (Apr to June) of 2017. For the UK market sector as a whole, the new estimates show that the volume of capital services grew by 1.9% in 2016, which is similar to the growth rates in 2015 and 2014 but lower than average growth in the decade leading up to the economic downturn. Provisional estimates for the first two quarters of 2017 suggest that capital services continued to grow at roughly 2% on a year-on-year basis.

As shown in Figure 6, capital services have continued to grow since the economic downturn in many industries, albeit at a slower rate in most industries than in the pre-downturn period. Only manufacturing (C), transportation and storage (H), and information and communications (J) have experienced a contraction in capital services since 2009. However, all but two industries – the utilities industries (D and E) and agriculture (A) – have seen the growth of VICS slow during the post-downturn period. This slowing of growth has been particularly marked in the services industries.

Figure 6: Average annual growth of capital services, 1997 to 2009 and 2009 to 2016

UK, market sector and selected industry components

Source: Office for National Statistics

Notes:

- A: Agriculture, forestry and fishing; B: Mining and quarrying; C: Manufacturing; DE: Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply and water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities; F: Construction; G: Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; H: Transportation and storage; I: Accommodation and food service activities; J: Information and communication; K: Financial and insurance activities; L: Real estate activities; M: Professional, scientific and technical activities; N: Administrative and support service activities; P: Education; Q: Health; and RSTU: other services.

Download this chart Figure 6: Average annual growth of capital services, 1997 to 2009 and 2009 to 2016

Image .csv .xlsThese variations in the growth rate of capital services across industries can be combined with changes in the level of labour input to provide insights into changes in labour productivity. All else equal, the larger (smaller) the value of capital services per hour worked, the greater (lower) the productive potential of each worker. As a result, changes in the capital services to labour ratio can be instructive for labour productivity. Figure 7 presents the indices of capital services, labour input (in the form of productivity hours) and the capital services to labour ratio, for the aggregate market sector.

Figure 7: Aggregate capital and labour indices

UK, market sector, Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 1997 to Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2017

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 7: Aggregate capital and labour indices

Image .csv .xlsThis analysis indicates that aggregate capital services increased sharply relative to labour input in the years up to 2008, resulting in an increase in the capital services to labour ratio. Over this period, labour productivity growth appears to have been supported by the growing availability of capital services per hour worked. This effect reached its peak in 2009. During the economic downturn, capital services fell slightly but hours worked fell much faster, causing the capital services to labour ratio to increase quite markedly, peaking in Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2010. However, this increase almost entirely reversed over the 2010 to 2014 period, as hours worked first recovered and then surpassed their pre-downturn level. This “capital shallowing” – firms increasing their labour input more sharply than their capital services – tends to hold back labour productivity. The capital services to labour ratio has been broadly unchanged since 2014, at roughly the level reached immediately prior to the economic downturn. The effect of these changes in capital to labour ratios on productivity will be examined in more detail in the Multi-factor productivity release, planned for publication in April 2018.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Intangible assets

Alongside these new estimates of capital services, we are also publishing the intermediate results of our ongoing work programme to develop statistics on investment in intangible assets in the UK. Intangible assets – which are also known as knowledge assets or intellectual capital – have played a prominent role in recent debates on productivity. Following the framework created by Corrado, Hulten and Sichel (2005) and previously estimated for the UK by Goodridge, Haskel and Wallis (2014), we have developed these estimates to support the debate in the UK, to provide input for discussions about future statistical regulations and for the purposes of productivity analyses. While some intangible assets are already included in official estimates of investment (such as software, and research and development) other assets are not (such as branding, design, and organisational capital). These new data provide an update to previous estimates of investment in the broader set of assets in the UK market sector to 2015.

Our findings suggest that current price investment in intangible assets was £134.2 billion in 2015, compared with £141.7 billion for investment in tangible assets (such as transport equipment, buildings and structures, and machinery and equipment) over the same period. This is the first time since 2000 that investment in tangible assets has been higher than investment in intangible assets (Figure 8). Over the longer term, investment in intangible assets grew more quickly ahead of the economic downturn and was more resilient between 2008 and 2010. However, while tangible investment fell more sharply during the economic downturn, it has since seen a relatively strong recovery. The largest intangible asset investments were in training, organisational capital, software, and research and development. These figures include a broader set of intangible assets than is currently included in international guidance on the measurement of investment in the national accounts – these additional assets account for approximately two-thirds of total intangible investment in recent years, adding £88.3 billion in 2015 to the £45.9 billion that is already capitalised.

Figure 8: Investment by asset class

Current prices, UK, 1997 to 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Download this chart Figure 8: Investment by asset class

Image .csv .xlsOur analysis also shows that some industries invest more in intangible assets as a proportion of total investment relative to other industries. These include the professional and scientific activities industry, which is dominated by spending in research and development, and the financial services industry, which is driven by spending on organisational capital. Production industries tend to invest least in intangible assets relative to their tangible investments, especially the agriculture, forestry and mining industries, and the utilities industry.

We have published these experimental figures as a first stage of our work to inform the debate around the role of intangible assets in the UK economy. While there are no current plans to incorporate these estimates into the national accounts, further development work is planned to feed into discussions on future international statistical regulations and to provide inputs for future experimental growth accounting work. This will enable us to analyse the effect on growth and productivity of measuring a broad range of intangible assets. Further work in this area will explore appropriate price indices and depreciation rates for these assets.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. International review of best practice in the publication of productivity statistics

Alongside this release, we are publishing a report on international best practice in the production of productivity statistics. This report, commissioned by Office for National Statistics (ONS) from the economic consultants, London Economics and DIW Econ, examines the productivity measures that are published by other national and international statistical organisations (NISOs) around the world and includes information on the range, timeliness, detail and frequency of the productivity data they produce. The report summarises the productivity publications of 21 NISOs and includes information on their detailed labour-, capital- and multi-factor productivity estimates.

This report finds that the UK has strengths in the measurement of labour productivity, but there are some areas where we can improve further to be best in class; that we are among the small number of NISOs to have published estimates of capital productivity; and that the work on multi-factor productivity ONS has been under-taking will make us amongst the best in the world for this statistic.

The primary aim of this report was to provide ONS with evidence on international best practice in the production and publication of productivity statistics. This was to identify areas in which ONS is performing comparatively well and to highlight practice from which we could learn. In particular, as we approach the conclusion of the two-year development plan that we set out in July 2016, this report provides important input for ONS’s future plans.

Specifically, this output gives us a sense of where the global frontier of productivity measurement lies and what is required to raise our current practice to that of the world-leaders. The results of this report and the implications for our longer-term development work will both be the subject of discussions at our user group, to be held in late March 2018. If you are interested in attending this event, please contact Productivity@ons.gov.uk.

The report finds that against this international yard-stick, ONS’s performance varies by measure. In our publication of labour productivity, our estimates are:

mid-pack in terms of their production speed – ONS’s flash estimate of productivity (published 45 days after the end of the quarter to which they relate) is faster than equivalent estimates in Australia (60 days), Canada (67) and Sweden (60), but slower than in the US (35) and France (31)

mid-pack in terms of their industrial granularity – ONS currently produces estimates for combinations of 50 individual industries and aggregations thereof; this compares favourably with Australia (16 industries), Italy (35) and the Netherlands (38), but is considerably less than in the US (380 industries) and Canada (322)

the UK is close to the global frontier in terms of regional labour productivity – ONS is among only six NISOs included in the survey to produce estimates of labour productivity for different regions

the UK is among only three countries that produce industry-by-region estimates of labour productivity

The report also highlights that there is room for improvement in the multi-factor productivity (MFP) estimates that ONS currently produces. At present, we publish multi-factor productivity on an annual basis – around 460 days after the end of the period to which the data relate, and among the slowest of the NISOs recorded here. ONS’s current MFP release is also among the most aggregated on an industrial scale of the organisations surveyed for this report: offering estimates of MFP for 10 industries, as compared with 35 in Italy, 39 in Canada and 145 in the US.

The report also notes that ONS is among the small number of NISOs to have published estimates of capital productivity – which estimates the value of output generated per unit of capital input used in production.

The report consequently provides some support for the analytical and development work that ONS has been undertaking over the past two years. In April 2017, we published the first estimates of quarterly regional labour input consistent with the UK’s headline labour productivity metrics. In July 2017, we published experimental labour productivity data at a more detailed level of industrial granularity for the 2009 to 2017 period, as well as the first industry-by-region labour productivity metrics for the UK consistent with headline data.

In October 2017, we published updated estimates of the UK’s labour productivity performance relative to the other G7 economies, as well as the first data on international comparisons of labour productivity by industry. This release extends this run of developments – including the first real regional labour productivity measures and an extended time series for our more detailed industry level estimates.

The weaknesses in the area of MFP to which the report alludes also provide further justification for the development programme that we have been undertaking and which will come to fruition in the coming months. In July and October 2016, we published estimates of quality-adjusted labour input (QALI) – an important ingredient for MFP – using a new, experimental methodology which will increase the industrial granularity of QALI to close to 60 individual industries on a quarterly basis. Alongside this release, we have published the first experimental volume index of capital services (VICS) results on a quarterly basis for a detailed breakdown of close to 60 industries.

Both developments will support a new quarterly growth accounting release from April 2018, which we hope will eventually provide MFP information at a lag of just 90 days after the period to which it relates for around 50 industries. This will move ONS from the very back of the timeliness pack to the very front and shift our level of industrial granularity from the very bottom, to around the middle of the pack.

While these improvements are considerable and will deliver a significant improvement, we recognise that there remains more to be done to transform our suite of productivity data to be comparable with among the best in the world. To this end, we plan to study the contents of this report in detail and to use its results alongside feedback from users to publish a Productivity Development Plan in April 2018. This will reflect on the advances made since the last development plan in July 2016.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys