Yn yr adran hon

- Overview

- Methodology

- Sexual orientation

- Gender identity

- Ethnic group

- Annex 1: Research methods used in evaluation of topics for the 2021 Census

- Annex 2: Summary of research undertaken for sexual orientation topic, December 2017 to November 2018

- Annex 3: Summary of research undertaken for gender identity topic, December 2017 to November 2018

- Annex 4: Summary of research undertaken for ethnic group, December 2017 to November 2018

- Annex 5: Sikh names research report 2018

1. Overview

Today (14 December 2018), the government has published a White Paper with its response to the recommendations Office for National Statistics (ONS) has made for the content of the 2021 Census. This report provides links to previously published research and recommendations and provides details of the additional research that supports the recommendations announced today.

Background

In May 2016, ONS published its response to the 2021 Census topic consultation in The 2021 Census – Assessment of initial user requirements on content for England and Wales: Response to consultation (PDF, 796.4KB). Within this report we provided details of topics where a final decision had been made to recommend whether those topics should or should not be included in the census. The report also listed those topics where further research was required before a final decision on the recommendation could be made. These topics were number of rooms, sexual identity (later changed to sexual orientation), gender identity, volunteering and supervisory status. We also stated that we were exploring administrative data potential for income, year last worked and armed forces.

In October 2017, we announced that we would be recommending a question on armed forces veterans. The exploration of administrative data had shown that the administrative data would not provide comprehensive data on those that left the forces before 1983 or on dependants of those who have been, or are in, the armed forces.

In December 2017, we published a 2021 Census topic research report, in which we confirmed that we would recommend the 2021 Census should not include questions on year last worked, volunteering or the number of rooms in the accommodation. We recommended that the year last worked question be replaced with a question asking if the person worked within the last year as this was all that was required to derive the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC).

The information in this update covers the remaining topics where a recommendation on inclusion has not been previously announced and which appear in the White Paper recommendations for the 2021 Census. These were sexual orientation and gender identity. It also covers research carried out since December 2017 to finalise recommendations on the tick-boxes for the ethnic group question, which has already been recommended for inclusion. We also report on our recommendations regarding supervisory status.

The recommendations put forward are based on extensive research and assessment using evaluation criteria that were set out in the May 2016 census topic consultation report (PDF, 796.4KB). These are copied in Section 2, Table 1. Those criteria consider a number of factors, which include:

alternative sources of data

data quality

public acceptability

respondent burden

financial concerns

questionnaire mode

Sexual orientation

In the December 2017 update, we reported that results from testing on this topic had been very positive. We also identified the need for more research to help us improve data quality and for further engagement with important stakeholders.

The focus of the work done since the December 2017 update has been on refining the question. The aim is to ensure the best quality data are produced that will meet users’ data requirements, while at the same time minimising the burden on respondents. The results of this testing and engagement work are described in Section 3, and the methodology is outlined in Annex 2.

We’re recommending the inclusion of a sexual orientation question in the 2021 Census. Testing has shown that it would be acceptable (to include this question on the census) and that it will deliver good quality data with minimal effect on overall response and respondent burden.

To improve acceptability and minimise burden, we’ve recommended that the question should:

only be asked of persons aged 16 years and over

explicitly ask respondents’ sexual orientation (rather than relying on the response options to tell the respondent what the question is about)

list “straight” before the equivalent term “heterosexual” in the first response option

include a write-in box for the “other” response option

include a “prefer not to say” response option

Our findings have shown the inclusion of a “prefer not to say” option would increase the number of people responding to the sexual orientation question. We believe the new question on sexual orientation should be voluntary. That is, nobody will need to tell us their sexual orientation if they don't want to. The government and UK Statistics Authority will consider how to ensure this is the case.

Gender identity

The December 2017 update outlined our progress in understanding the concepts around the topic of gender identity as well as the testing done to date on potential question designs. We said that we would continue to consider whether and how to collect information on gender identity, alongside collecting information on sex in terms of “male” and “female”.

We had undertaken testing of the public acceptability of including this topic in the 2021 Census but had not yet developed a question that accurately collected the information required. The approaches to data collection considered and the results of testing and engagement work are described in Section 4, and the methodology is outlined in Annex 3.

We’ve concluded that neither a sex nor a gender question alone can meet the user need. Adding a question about gender identity or asking if a respondent is transgender is publicly acceptable and would meet most of the user need.

In relation to the sex question, to maintain or improve data quality we’ve recommended:

the wording of the sex question and available response options should remain the same

there should be a guidance note on the sex question stating that a gender identity question will follow later

In order to collect robust data on gender identity, that is publicly acceptable and meets user needs, we’ve recommended that the question should:

only be asked of persons aged 16 years and over

be separate to the question on sex

include a write-in box to allow individuals to record their gender identity where this is not male or female

include a “prefer not to say” response option

Similar to sexual orientation, we believe the new question on gender identity should be voluntary. That is, nobody will need to tell us their gender identity if they don't want to. The government and UK Statistics Authority will consider how to ensure this is the case.

Ethnic group

In December 2017, we identified four groups for which we needed to undertake further work before we could decide whether to recommend any new tick-boxes within the ethnic group question. We recognise the needs from all four groups. The groups were: Roma, Somali, Sikh and Jewish.

In the December 2017 update, we said that we would engage further with stakeholders to assess commonality of views within these four groups. We also said we would undertake further research to assess whether the inclusion of new tick-boxes would collect sufficient quality information to meet the user need.

The results of testing and engagement work are described in Section 5, and the methodology is outlined in Annex 4.

Against our publicly stated criteria, we have concluded that an additional response option of Roma be included. This has been assessed as having the strongest case for inclusion. The testing and research work also shows us that addition of a “Roma” tick-box within the “White” category is acceptable to the community, and the placement near “Gypsy or Irish Traveller” would mean that respondents could easily find it.

In contrast, the focus groups held for Sikhs, Somalis and Jewish showed that adding a tick-box would not be acceptable due to singling out specific countries of ancestral origin, or religious backgrounds.

To meet user needs whilst remaining publicly acceptable, we’ve recommended that the question should:

include a tick-box for “Roma” within the “White” category under “Gypsy or Irish Traveller”

include an option for those selecting “African” within the “Black, African, Caribbean or Black British” category to write in a more specific ethnic background

Online, the question will be split into two stages to reduce respondent burden and, for both online and paper versions, the readability of the question will be increased by removing slashes between terms.

In addition, online “search-as-you-type” functionality will help to ensure that people can tell us how they wish to identify themselves. The ethnic group question has previously included a write-in option, to allow respondents to self-identify as they wish when a tick-box is not available. With the online questionnaire, a comprehensive list of suggestions, including “Somali”, “Sikh” and “Jewish”, will be available. Respondents will, however, still be able to state identities not listed.

Supervisory status

The response to the 2021 Census topic consultation stated that we would further investigate whether and how to collect data on supervisory status. The purpose of supervisory status data is to allow the derivation of National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) and Approximated Social Grade, and to improve the coding of occupation data.

In December 2017, we outlined our progress on exploring options for deriving NS-SEC without supervisory status. We collaborated with academics to explore options for deriving NS-SEC that still meet users’ need for continuity without the need for supervisory status data. Academics used Labour Force Survey data and the Standard Occupational Classification 2010: SOC 2010 to estimate the impact of moving to a census-specific NS-SEC derivation matrix. The census-specific matrix correctly derived 92.6% of the 13 operational categories.

We’ve concluded that the reduction of the quality of NS-SEC if supervisory status is removed is too great. Therefore, we’re recommending that supervisory status is collected in 2021.

Full list of topics

The final list of topics we recommend collecting in the 2021 Census is detailed in this section. Work will continue until early 2019 to finalise the wording of questions and their position on the questionnaire, and to optimise the design for both online and paper collection.

For households

Relationships within the household

Type of accommodation

Self-containment of accommodation

Number of bedrooms

Type of central heating

Tenure and type of landlord (if renting)

Number of cars or vans

For communal establishments

- Type of establishment (including who it caters for and who is responsible for managing it)

For residents in communal establishments

- Position within the establishment

For visitors in households

- Name

- Sex

- Date of birth

- Location of usual residence

For residents in households and communal establishments

Name

Date of birth

Sex

Marital/legal civil partnership status

Ethnic group

National identity

Amount of unpaid care provided

General health

Long-term health problem or disability

Qualifications

Long-term international migration

Short-term international migration

Address one year ago

Citizenship (via passport held)

Religion

Welsh language skills (in Wales only)

Main language used

English language proficiency

Economic activity

Occupation

Industry

Method of transport to place of work

Supervisory status

Address of place of work

Address and type of second residence

Second residence

Students’ term-time address

Armed forces

Gender identity

Sexual orientation

2. Methodology

Evaluation method

The census is a compulsory exercise carried out on a household enumeration basis; each respondent is currently required to complete all relevant questions on the questionnaire except the question on religion.

As such, it’s important that there’s a clear basis for determining whether topics are included. The basis for the evaluation of topics for the 2021 Census is broadly the same as was successfully used to design the 2011 Census. However, we’ve made some changes to make the evaluation criteria stronger and more transparent, and to reflect the move to a primarily online census.

The evaluation criteria consists of three groups. Each topic or subtopic has been continually evaluated against the criteria within each of the groups, shown in Table 1, since the publication in May 2016 of our response to the 2021 Census topic consultation. This includes consideration of any legal obligations on us to collect information.

The evaluation criteria, and the evaluation of each topic against the criteria, are described in the 2016 consultation response.

| User requirement | Other consideration – impact on | Operational requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Data quality | Maximising coverage or population bases |

| Small geographies or populations | Public acceptability | Coding of derived variables and adjustment for non-response |

| Alternative sources | Respondent burden | Routing and validation |

| Multivariate analysis | Financial concerns | |

| Continuity and comparability | Questionnaire mode |

Download this table Table 1: Evaluation criteria

.xls .csvThe user requirements criteria are critical. Topics must carry a strong and clearly defined user need. A robust case is required for any topic to be included in the 2021 Census.

The “other considerations” criteria have predominately been used in conjunction with the user requirements assessment to steer the development of the census questions and questionnaire. The impact of overall respondent burden has been assessed within this set of criteria, as have design and layout constraints for the online census questionnaire. This includes considerations of the layout of questions on different sizes of mobile device.

Research and testing methods

In developing or updating questions for the 2021 Census, we’ve used a variety of different research methods. Broadly speaking, the research methods we’ve used can be categorised into qualitative and quantitative methods.

Qualitative methods are used to gain insight into a respondent’s understanding or interpretation of a question or concept. They are particularly useful in identifying problems with a question or question design. They will usually involve a smaller number of respondents and their purpose is not to give a representative picture of a population.

Quantitative methods are primarily used to make inferences about a population and to evaluate data quality issues. They will usually involve a survey, with data being captured using different modes (paper, online or interviewer administered) as appropriate.

A list of the research methods used in the development of the 2021 Census questionnaire is shown in Table 2. A full description of each of these research methods appears in Annex 1.

| Qualitative research methods | Quantitative research methods |

|---|---|

| Focus groups | Small-scale individual online surveys |

| Informal interviews at community events | Small-scale individual online omnibus surveys |

| Group discussions at community events | Large-scale multi-modal household surveys (replicating census context) |

| Cognitive interviews |

Download this table Table 2: Summary of research methods used in developing the 2021 Census questionnaire

.xls .csvFurther research and testing plans

For some topics, additional testing is still required to develop a question that meets user needs, is acceptable to the public and relevant communities, and is easy to answer. Remaining testing across topics includes:

considering question placement within the questionnaire

reviewing instructions and guidance

testing online validation and “search-as-you-type” for write-in options

When developing new or reworded questions, we also need to develop a version in Welsh for use in Wales. We’ve already conducted a process to develop questions in Welsh. We’ve conducted focus groups and cognitive in-depth interviews with members of the public to review some questions in Welsh. We’ve commissioned an external research agency with Welsh-speaking research staff to undertake cognitive testing of the full suite of proposed questions both on paper and online, in the Welsh language. Final recommendations for the Welsh question designs are for National Assembly for Wales approval.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys3. Sexual orientation

Background

In our response to the 2021 Census topic consultation, we identified a clear need among data users for improved information on sexual orientation in relation to:

policy development

service provision and planning

equality monitoring

resource allocation

reflecting change in society

We highlighted that the Equality Act 2010 makes it unlawful to discriminate against people because of sexual orientation in relation to provision of goods and services, employment, or vocational training. Furthermore, the Act introduces a public sector Equality Duty, which requires that public bodies consider all individuals when shaping policy, delivering services and interacting with their own employees. They must also have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations between different people when carrying out their activities.

No other country has yet included a question on sexual orientation in their national census. However, both Scotland and Northern Ireland are considering a sexual orientation question for their 2021 Censuses.

National Records for Scotland (NRS) has recently published a sexual orientation topic update (PDF, 839KB). NRS’s research and testing has been positive and a sexual orientation question has been proposed for inclusion in the 2021 Census in Scotland.

In their topic consultation, Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) identified a user need for information on sexual orientation. NISRA outlined that more work was needed to understand the user requirements for this topic and how the user need could be met. No final recommendations have been made about collecting information on sexual orientation in Northern Ireland.

In the response to the topic consultation for the 2021 Census in England and Wales, we also assessed the topic against other criteria. Despite a high user need, our assessment, carried out in 2016, indicated that a sexual orientation question may have a high impact on data quality and public acceptability. We have not previously included such a question on the census. As such, concerns were around:

impact on overall census response

quality and completeness of response to the sexual orientation question

difficulties in, and appropriateness of, statistically estimating (or imputing) answers for non-response to the question

ability to answer the question on the behalf of others in their household (that is, by proxy)

To assess these concerns, we developed a research and testing plan that consisted of the following:

inclusion of a question in the 2017 Census Test across England and Wales

a public acceptability survey in England and Wales

development of statistics from our social surveys

In December 2017, we provided a comprehensive update on these, which set out the research and the 2017 Census Test work. In that update we said:

“We have identified some further research which may improve quality further and will be undertaking further engagement with key stakeholders. These last activities, alongside space constraints on a paper questionnaire, will inform our decision on whether to recommend inclusion of a question on sexual orientation in the 2021 Census.”

The focus of the remaining work done since the December 2017 update has been on refining the question to ensure the best quality data are produced. The aim is to meet users’ data requirements, while at the same time, minimising the burden on respondents. Included in this work was an exploration of different methods to make the question voluntary and inclusion of explicit reference to the topic, sexual orientation, within the question wording.

Stakeholder engagement

We have worked with stakeholders to identify the correct terminology for the question and to decide what the appropriate age group is to ask these questions of.

Engagement with other collectors of sexual orientation information has also shown the umbrella term “sexual orientation” is favoured. For example, the NHS has since developed the Sexual Orientation Monitoring Standard and Stonewall now provides guidance on collecting information on sexual orientation (PDF, 4.53MB).

The terminology used to label the Government Statistical Service (GSS) Harmonised Principle question was also updated in May 2018 to “sexual orientation” to make it in line with the protected characteristic defined in the Equality Act 2010 (sexual orientation).

Additionally, we’ve reordered the terms within the response option for those who are heterosexual so that it reads “Straight / heterosexual”, as this aided respondent understanding within this population. We worked with lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) organisations to ensure this was considered acceptable within the LGB community.

In May 2018, we held a meeting with important stakeholders to test the assumption that the minimum age at which the sexual orientation question should be asked in the 2021 Census is age 16 years. In general, there was support for asking the question to those aged 16 years and over only. Two important justifications agreed by the stakeholders for this decision relate to data quality. First, responses for children under the age of 16 years are likely to be completed by the householder on their behalf. The householder may not know the child’s sexual orientation, which will reduce the quality, and therefore usefulness, of the data collected. Secondly, children under the age of 16 years may not yet know their sexual orientation and this becomes more likely the younger the child. At age 16 years, children reach the age of consent and the minimum age for marriage. They can therefore in most cases be assumed to know their own sexual orientation by that age.

However, it was highlighted that there’s still likely to be under-reporting of the LGB+1 population among those aged 16 to 18 years because, as with children aged under 16 years, the householder will generally complete the questionnaire on their behalf.

Further discussions with government departments indicated that age 16 years and over is an appropriate age range for collecting information on sexual orientation. In 2017, NHS England and LGBT Foundation published guidance on collecting sexual orientation information within all health services in England and stated that the guidance is applicable to all patients or service users aged 16 years and over (see Sexual Orientation Monitoring: Full Specification from NHS England for more information). During 2017, the Government Equalities Office (GEO) ran a survey to understand the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people living in the UK. To participate, respondents needed to be aged 16 years and over (see Government Equalities Office, National LGBT survey, 2017).

The Government Statistical Service Harmonised Principle on sexual orientation also recommends that the question should be asked to those aged 16 years and over.

Alternative sources

One of the main criteria underpinning the decision to include a new question in the census, is whether the user need can be met through different data sources. Were other alternative data sources available, the case for including a question could be insufficient. We’ve therefore continued to examine the feasibility of using administrative data and alternative sources to obtain information on sexual orientation to meet user need.

In 2017, we published Experimental Statistics on sexual identity drawn from the Annual Population Survey (APS). Although this provided estimates of sexual identity for the UK, constituent countries, and English regions, it is not possible to produce robust estimates for all local authorities.

Other data sources examined included the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) and the British National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). In both cases, the population coverage was too limited to meet user needs.

In terms of administrative data, we have explored vital statistics and registration data on marriages and civil partnerships, NHS health records, and Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA) data. None of these sources could meet the user need of estimating the lesbian, gay and bisexual population at small geographies.

The Government Equalities Office (GEO) conducted a national LGBT Survey in July 2017. The online survey ran for 12 weeks and received 108,100 valid responses from individuals aged 16 years and over who were living in the UK and self-identified as LGBT or intersex. Whilst this survey can provide information on the size of different groups that make up the LGBT population within this sample, it is of limited use in terms of making inferences about the wider population. This is because of the method used to construct the sample (it was not a sample of the general population).

From this work we’ve found no sources of sexual orientation information from administrative data and alternative data that we can use to meet the full user need, mainly because they do not provide coverage of the whole population at small geographies. As estimates, the data sources that do exist do not provide sufficient information for service providers to carry out targeted work at local authority level in England and Wales.

Research and testing

Since December 2017, we’ve undertaken further research on the topic of sexual orientation. Details of this research are described in Annex 2.

As mentioned in the December 2017 update, we’ve tested whether using a “prefer not to say option” is the best way to make the sexual orientation question voluntary. Previous qualitative research and the quantitative public acceptability survey indicated that including this option would make the question more acceptable.

We conducted a large-scale quantitative test of 13,673 households across England and Wales (Annex 2: A). This tested three forms of the question:

one with a “prefer not to say” option for the response

one with an instruction that the question was voluntary

one with neither a “prefer not to say” option or a voluntary instruction

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of the three samples, each with a different design of the sexual orientation question.

This test found that the sample with the “prefer not to say” option (Group 1) had the highest response to the survey (34.8%) and the lowest incidence of failure to answer the question (Table 3), although neither of these differences were statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. For the Group 1 sample, 2.3% of respondents identified as LGB. This proportion is very similar to that of the 2017 Census Test (2.4%) and the 2016 Annual Population Survey (2.0%) (Table 4).

Across all three samples, only one respondent dropped out when they reached the sexual orientation question. This indicated that this question did not stand out compared with other questions. A similar conclusion was drawn from the 2017 Census Test, whereby the online drop-off rate was similar to that of other identity questions such as ethnic group.

| Sample group | Group 1: ”Prefer not to say” response option | Group 2: Instruction that the question was voluntary | Group 3: Neither instruction nor response option |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response to survey (%) | 34.8 | 33.0 | 33.2 |

| Non-response to the sexual orientation question (%) | 1.6 | 7.8 | 2.4 |

| Distribution of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) population (%) | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Base (responding households) | 1,578 | 1,490 | 1,504 |

Download this table Table 3: Testing sexual orientation privacy options

.xls .csv

| Annual Population Survey 2016 (%) | 2017 Census Test (%) | Quantitative test November 2017 to January 2018 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question design | Voluntary | Voluntary | “Prefer not to say” option |

| Questionnaire mode | Interviewer led, face-to-face and telephone | Self completion , paper and online | Self completion, paper and online |

| Heterosexual or straight | 93.4 | 88.7 | 93.5 |

| Gay or lesbian | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Bisexual | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Other, please specify | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Prefer not to say | - | - | 2.3 |

| Don’t know or refuse, or missing | 4.1 | 8.4 | 1.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Download this table Table 4: Distribution of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) population

.xls .csvAlongside the research exploring a “prefer not to say” option, we carried out qualitative and quantitative research to further investigate public acceptability, data quality, and respondent burden.

Our qualitative work (Annex 2: B) suggests that including a question on sexual orientation would not impact overall response to the census. When asked what they would do if they saw the question on the census, none of the participants said they would definitely not answer it and no one said they would stop completing the form.

Participants were also asked whether they found a question on sexual orientation acceptable. Several participants were in favour of its inclusion, considering it as inclusive and a standard question they regularly encounter. However, there were some negative responses, questioning the relevance of the question in a census context and why it needed to be labelled. These conclusions validate earlier findings.

Across our quantitative tests, there are consistencies in respondents’ write-in responses for the “Other, write in” option. “Asexual” and “pansexual” were the most frequently written valid responses in our large-scale quantitative test (Annex 2: A). These responses have been used in other tests and it’s our intention to include these as examples in our guidance for this question. Within the write-in responses, there were a small number of incidences of respondents providing “mischievous” answers – these were classified as non-response.

The other two quantitative tests were online surveys (Annex 2: C and D). With these tests, there was no expectation of providing an accurate distribution of the LGB population in England and Wales because of the sampling methods used. The intention of these tests was to assess respondent burden and public acceptability of a sexual orientation question.

The August 2018 test (Annex 2: D) was used to analyse the time taken for respondents to record an answer, which is an accepted measure for how burdensome or difficult a respondent finds it to complete a question. The results showed the average time taken was in line with other questions of similar length, for example, a question on general health.

Both omnibus tests indicate that respondents find a question on sexual orientation acceptable. There was no difference in the number of persons who stopped completing the survey at the sexual orientation question when compared with other questions in either omnibus. Furthermore, there were no more than three incidences of “mischievous” answers in these tests.

Differences in response by mode (online or paper) were found in the 2017 Census Test (see December 2017 report for more detail) whereby non-response to the sexual orientation question was higher for individuals answering on paper compared with online. The same effect was found in the quantitative test (Annex 2: A), where respondents were significantly less likely to answer the question if they completed the survey on paper. It is our intention to undertake further research into mode effects in the lead up to the 2021 Census.

Summary

Since December 2017, we’ve engaged with stakeholders and continued our research to understand how we can further improve data quality.

We’re recommending the inclusion of a sexual orientation question in the 2021 Census in England and Wales. Testing has shown that it would be acceptable to include a sexual orientation question in the census and that it will deliver good-quality data with minimal effect on overall response and respondent burden. To improve acceptability and minimise burden, we’ve recommended that the question should only be asked of persons aged 16 years and over. We’re continuing to look at how we can mitigate the effect mode has on this question.

Our findings have shown the inclusion of a “prefer not to say” option would increase the number of people responding to the sexual orientation question. We believe the new question on sexual orientation should be voluntary. That is, nobody will need to tell us their sexual orientation if they don't want to. The government and UK Statistics Authority will consider how to ensure this is the case.

Notes for: Sexual orientation

- LGB+ is used to refer to persons who define their sexuality as lesbian, gay, bisexual or in another way such as queer, asexual and pansexual.

4. Gender identity

Background

The 2021 topic consultation identified a need for data on gender identity for policy development and service planning; especially in relation to the provision of health services for the transgender population. The introduction of the Equality Act 2010 further strengthens the user requirement for those with the protected characteristics of gender reassignment.

Some members of the public also reported that they were unable to complete the 2011 Census accurately as it included the current Government Statistical Service (GSS) harmonised sex question, which only has two categories: “male” and “female”. While acknowledging the need to consider change, a major concern was not to damage the information already collected through the “male” or “female” sex question, which is an essential variable that feeds into population projections. These projections underpin decision-making, planning and resource allocation across central and local government. The research was focused to ensure that we fully understood this issue.

In 2011, Scotland and Northern Ireland also used the GSS Harmonised Principle for collecting data on sex.

National Records of Scotland (NRS) recently published its sex and gender identity topic report, which outlines the research and testing it has been undertaking for Scotland’s Census 2021. This report states that NRS has been testing several different question approaches and in their Plans for Scotland’s Census 2021: September 2018 (PDF, 804.5KB) report, it states that a transgender status question is being proposed.

In its 2021 Census topic consultation, the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) identified a user need for information on gender identity. NISRA outlined that more work was needed to understand the user requirements for this topic and how they could be met. NISRA has not made any final recommendations about collecting information on gender identity.

In response to our own consultation, as well as publishing a topic report, we published a Gender identity research and testing plan (published in May 2016). It outlined next steps including engaging with relevant stakeholders, learning from other national statistical agencies and identifying alternative data collection options. Within the plan, we also committed to undertaking a review of the 2009 Transgender Data Position Paper. Since then, we’ve published a Gender identity update (published in January 2017), which detailed changes and progress around the topic of gender identity and covered our plans for researching the topic further.

This is a developing area of research in many countries. Currently, no European country collects gender identity data in their census. However, India, Nepal, Australia and New Zealand have provided various options for individuals to respond to the sex question other than selecting a binary option in their previous censuses. We’re working closely with other statistics agencies to understand the different approaches possible for collecting information on gender identity.

The December 2017 census topic update outlined our progress in understanding the concepts around the topic of gender identity, as well as the testing done to date on potential question designs. Our assessment at that time was that we would continue to consider whether and how to collect information on gender identity, alongside collecting information on sex in terms of “male” and “female”.

Stakeholder engagement

In the December 2017 update, we discussed our work since the topic consultation to further understand the user needs around the topic of gender identity. We said that we understood that there is a consistent data need for a transgender population estimate, including individuals of all ages, and a respondent need for being able to self-identify. We’ve been balancing this data need with the high-priority data need for information on sex in terms of “male” and “female” and ensuring there is no risk to the quality of data collected on this.

We’ve also engaged with the Government Equalities Office (GEO) to understand the changing legal and policy context around the topic, for example, the development of the LGBT Action Plan 2018.

In May 2018, a meeting was held with important stakeholders to test the assumption that the minimum age at which the gender identity question should be asked on the 2021 Census is age 16 years. In general, there was support for asking the question to those aged 16 years and over only.

The main justification for making this decision for the 2021 Census relates to data quality. Responses for children aged under 16 years are likely to be completed by the householder, which in most cases is a parent. The householder may not know the child’s gender identity, which will reduce the quality, and therefore usefulness, of the data collected.

However, it was highlighted that there’s still likely to be under-reporting of gender identities that differ to the sex registered at birth among those aged 16 to 18 years because, as with children aged under 16 years, the householder will generally complete the questionnaire on their behalf.

Alternative sources

In the December 2017 update, we said we would identify alternative options for meeting the user requirement for data. This is because, as discussed for the sexual orientation question, one of the main criteria underpinning the decision to include a new question on the census is whether the user need can be met through different data sources.

We’ve confirmed that there are currently no administrative sources that record transgender, including non-binary, identities for the whole population, and, therefore we cannot meet the user need through administrative data.

We’ve also previously assessed that, given the predicted small size of this population, it would be hard to meet the user needs through sample surveys. However, while we are still exploring options to use sample surveys, it is unlikely that this will be achieved ahead of the 2021 Census.

Research and testing

Since December 2017, we’ve undertaken further research on the topic of gender identity. Details of this research are described in Annex 3. When we reported on this topic in December 2017, three question approaches had been tested. These were:

approach 1 – the 2011 Census sex question

approach 2 – the 2011 Census sex question with the addition of “other’’

approach 3 – a two-step question design with separate sex and gender identity questions

We concluded that none of the three question approaches would fully meet the requirement for a reliable estimate of the transgender population and we committed to further question development and testing.

We’ve now concluded that we should not change the sex question from 2011 because it would risk the quality of data collected on sex as “male” and “female”, which are imperative for population estimates. We also concluded that a two-step question design, such as in approach 3, was the most acceptable. As a result of this, we looked at including a guidance note on the sex question to indicate that a separate gender question would follow later. We also further developed the second question to give transgender people the opportunity to self-define their identity.

This led us to a fourth question approach:

- approach 4 – a two-step question design, with a binary sex question that includes an explanation that a separate gender question is asked later, and a gender identity question with an open response option to be asked of those aged 16 years and over

The question also included a “prefer not to say” response option, bringing it in line with the approach being taken on the sexual orientation question. That is, nobody will need to tell us their gender identity if they don't want to.

Our qualitative research, which has focused on approaches 3 and 4, confirmed that asking a gender identity question on the 2021 Census is broadly acceptable. Our qualitative testing (Annex 3: A and B) has identified that this acceptability is linked to several factors.

The write-in response option

Acceptability is increased with the inclusion of the write-in response option as it allows people the freedom to write how they personally identify. This is important because the language related to this topic is developing and there are a variety of identities with which people may want to identify.

The minimum age at which the question will be asked

Participants in our research were concerned about parents providing a response on behalf of other household members aged 15 years or under. Having an age limit of age 16 years and over was more acceptable.

The increased privacy of being able to request an individual form

This added function means that respondents do not have to disclose their gender identity to others in their household. The option to request an individual form to respond in private also reduces the concern around this.

The “prefer not to say” response option

The inclusion of a “prefer not to say” response option made the question more acceptable, as it meant there is a way for someone to not disclose their transgender history. This is particularly important for those who have a Gender Recognition Certificate who may not want to disclose their transgender history.

The guidance note on the sex question

We added a guidance note to the sex question stating that there would be a separate question on gender. This was important as it lets transgender, including non-binary, participants know they will be able to identify their gender later. It also helped them to understand how they should answer the sex question. Respondents also liked that we had established a difference between sex and gender. There were no associated problems with the guidance amongst participants who were cisgender, that is, participants whose sex and gender were the same. On the whole, they either did not read the guidance note or understood why it was included without it impacting on their ability to respond easily.

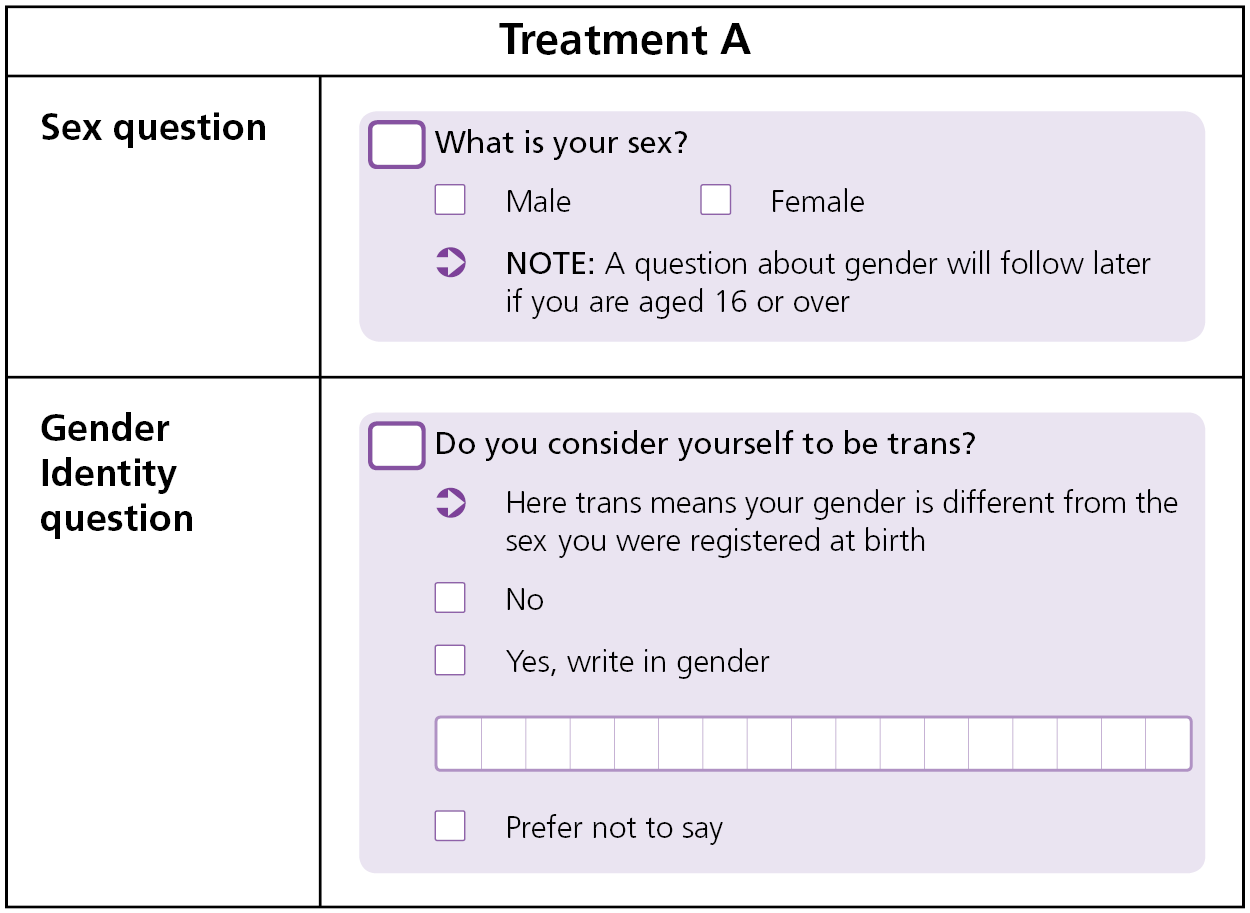

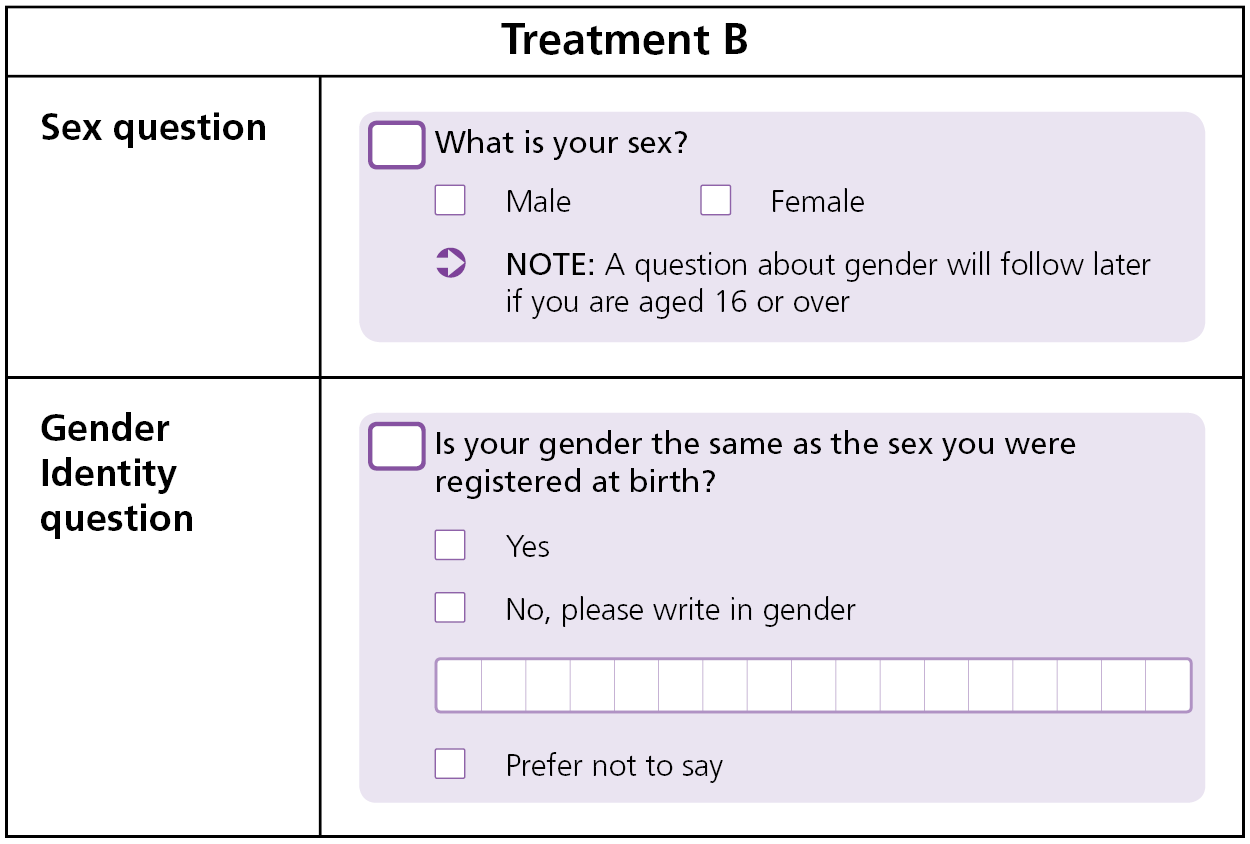

Within question approach 4, there are two alternative question wordings being considered. We’re undertaking a large-scale quantitative test (Annex 3: C) to help understand the effect of the remaining two options for question wording on response rates and data quality, along with public acceptability testing of different questions. The fieldwork stage of this is complete and we’re in the process of collating and analysing the data. This report includes initial findings from this test. The different question approaches and wordings tested can be seen in Figures 1 to 3.

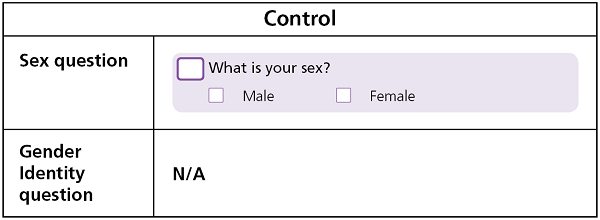

Figure 1: Sex and gender identity questions, control group

Download this image Figure 1: Sex and gender identity questions, control group

.png (18.1 kB)Figure 2: Sex and gender identity questions, treatment A

Download this image Figure 2: Sex and gender identity questions, treatment A

.png (40.3 kB)Figure 3: Sex and gender identity questions, treatment B

Download this image Figure 3: Sex and gender identity questions, treatment B

.png (36.0 kB)The public acceptability questions in this large-scale quantitative test complement the findings from the qualitative research (Annex 3: A and B) and from earlier quantitative testing that was reported on in the December 2017 update. Respondents were asked whether they thought it was acceptable to include a gender identity question in the census. Over 66% of respondents for treatment A, and over 84% of respondents for treatment B, thought that asking a transgender status question was acceptable (see Figures 2 and 3 for treatment questions).

The data quality also reflects the public acceptability of these questions. For example, we found that the inclusion of a gender identity question did not increase the overall non-response of the survey. The control and both treatment groups had an overall response rate of between 33.7% and 34.9%. There was also no difference in the proportion of returns online and on paper across the three groups. This response rate was higher than we would expect for a voluntary, self-completion, mixed-mode (paper and online) survey with no field follow-up. This gives weight to the robustness of these results.

Added to this, only 0.1% of those in each of the sample groups stopped completing the survey altogether at the gender identity question. Taking these results into account, we do not anticipate any impact on response to the whole census as a result of including a gender identity question.

A further indicator of acceptability is the level of non-response for a particular question. In this case, non-response to the gender identity question was slightly higher for treatment group A than treatment B, but was generally in line with other similar questions. This shows that people are generally willing to provide an answer for a gender identity question. The two versions of the gender identity question used in the large-scale quantitative test included a “prefer not to say” response option. This response was included as a way of giving respondents the choice to not answer the question if they did not want to. The only other question in the test where this response option was included is the question on sexual orientation. In the large-scale quantitative test, we found that there were lower levels of “prefer not to say” responses to the gender identity question than for sexual orientation. This is further evidence of the level of acceptability of this topic.

The large-scale quantitative test (Annex 3: C) was also used to analyse the time taken for respondents to record an answer. This is an accepted measure for how burdensome or difficult a respondent finds it to complete a question. Both treatment A and B versions of the gender identity questions tested took around the same amount of time to complete as comparable questions with similar levels of complexity (for example, main language). We also looked at the impact of adding additional guidance to the sex question (signposting that a separate gender question would be asked later). We found that the time taken to complete the version of the sex question with the guidance was only slightly greater than the time taken to complete the sex question without the guidance.

Summary

Since December 2017, we have engaged with stakeholders and continued our research and testing to identify an approach to collecting information on gender identity in the 2021 Census that:

is acceptable

helps address the respondent need

is easy to understand

is easy to answer

collects the required information to meet user needs

We’re recommending the inclusion of a gender identity question that collects information on those whose gender is different from their sex assigned at birth in the 2021 Census. The research and testing has shown that it would be acceptable and would have minimal effect on overall response and respondent burden. To improve acceptability and minimise burden, we’ve recommended that the question should only be asked of persons aged 16 years and over and should include a “prefer not to say” response option. We have not found any effect caused by mode of collection (paper or online) on the data collected.

We believe the new question on gender identity should be voluntary. That is, nobody will need to tell us their gender identity if they don't want to. The government and UK Statistics Authority will consider how to ensure this is the case.

We’re working closely with both NRS and NISRA to ensure that UK outputs for sex in terms of “male” and “female” will be harmonised.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys5. Ethnic group

Background

The 2021 topic consultation (PDF, 796KB) identified a continued need for data on ethnic group in order to understand inequality, inform and monitor policy development, allocate resources and plan services. Our response to the topic consultation set out details of the research to be undertaken for this topic.

We committed to undertake a review of the ethnic group response options, involving a consultation with stakeholder groups that have expressed an interest in this question. We also confirmed we would use similar methodology to that used prior to the 2011 Census. The prioritisation evaluation considered user need, alternative sources, data quality, public acceptability and comparability with the previous census.

In July 2017, we updated users on our progress towards designing the 2021 Census questionnaire, with a series of roadshow events in Birmingham, Cardiff, London and Newcastle. In the update on ethnic group, we stated that the current assessment was to maintain the response options previously used in the 2011 Census.

Following this we received correspondence from multiple data users, and as a direct result held a Population and Public Policy Forum on census topics in December 2017. In our response to the feedback from this forum we said:

“We need to continue to understand the views of all these communities. We also need to ensure we balance the needs of many different needs while making it easy for respondents to answer these questions.”

In the December 2017 update, we identified four groups where we needed to undertake further work before we could decide whether to recommend any new response options. We recognise the needs from all four groups. We’ll meet the user needs of the groups in different ways. The groups are:

Roma

Somali

Sikh

Jewish

We also confirmed that we were not planning any further work on the other 51 requests for new response options that were put forward. For people covered by these requests, the online “search-as-you-type” capability will help to ensure they can tell us how they wish to identify their ethnicity.

We also said:

“In order to finalise our views on the ethnic group categories, we need to engage further with stakeholders to assess commonality of views within different communities, undertake further research to assess whether the inclusion of new categories will collect sufficient quality information to meet the user need and that our conclusions are compliant with our legal obligations”.

Since December 2017, we’ve continued to work with stakeholders and have accepted further evidence of the user need. We’ve also evaluated effect on data quality, public acceptability and clarity (respondent burden) of the potential use of tick-boxes for the four identified groups.

This work had two streams. These were engagement with stakeholders with a need for data for one or more of the groups and testing to understand how respondents from each of these communities would interact with a tick-box if it were to be added. The details of the research are described in Annex 4.

The qualitative work included a series of focus groups (Annex 4: A). Our aim was to get an in-depth understanding of the issues and to explore the impact of the inclusion or non-inclusion of a tick-box for each community. This took into consideration how acceptable each response option was and what impact its inclusion would have on data quality and clarity. We procured independent qualitative research to undertake these focus groups. This research was conducted for ONS by Kantar Public. The report, Focus groups to consider the addition of possible new tick-boxes, is available on the Kantar Public website.

This research was supplemented by further qualitative work including:

informal interviews at Roma community events (Annex 4: B and E)

focus groups to understand the impact on the Gypsy or Irish Traveller community of potentially adding a “Roma” tick-box (Annex 4: C); this research was conducted for ONS by Kantar Public and the report, Gypsy Irish Traveller Question Testing, is available on the Kantar Public website. Kantar conducted two further pieces of research on our behalf, focus groups to consider the addition of possible new tick boxes and Colour Terms & Categorisation Question Testing.

cognitive interviews with Black, African, Caribbean or Black British participants to understand the best way to obtain more detailed data on ethnically Somali individuals (Annex 4: F)

Following the qualitative work, we undertook a small-scale online survey to understand the acceptability in a general population sample of different ethnic group response options. These included the four proposed new tick-boxes (Annex 4: D). This showed that respondents were confident answering the ethnic group question and comfortable with the tick-boxes being considered.

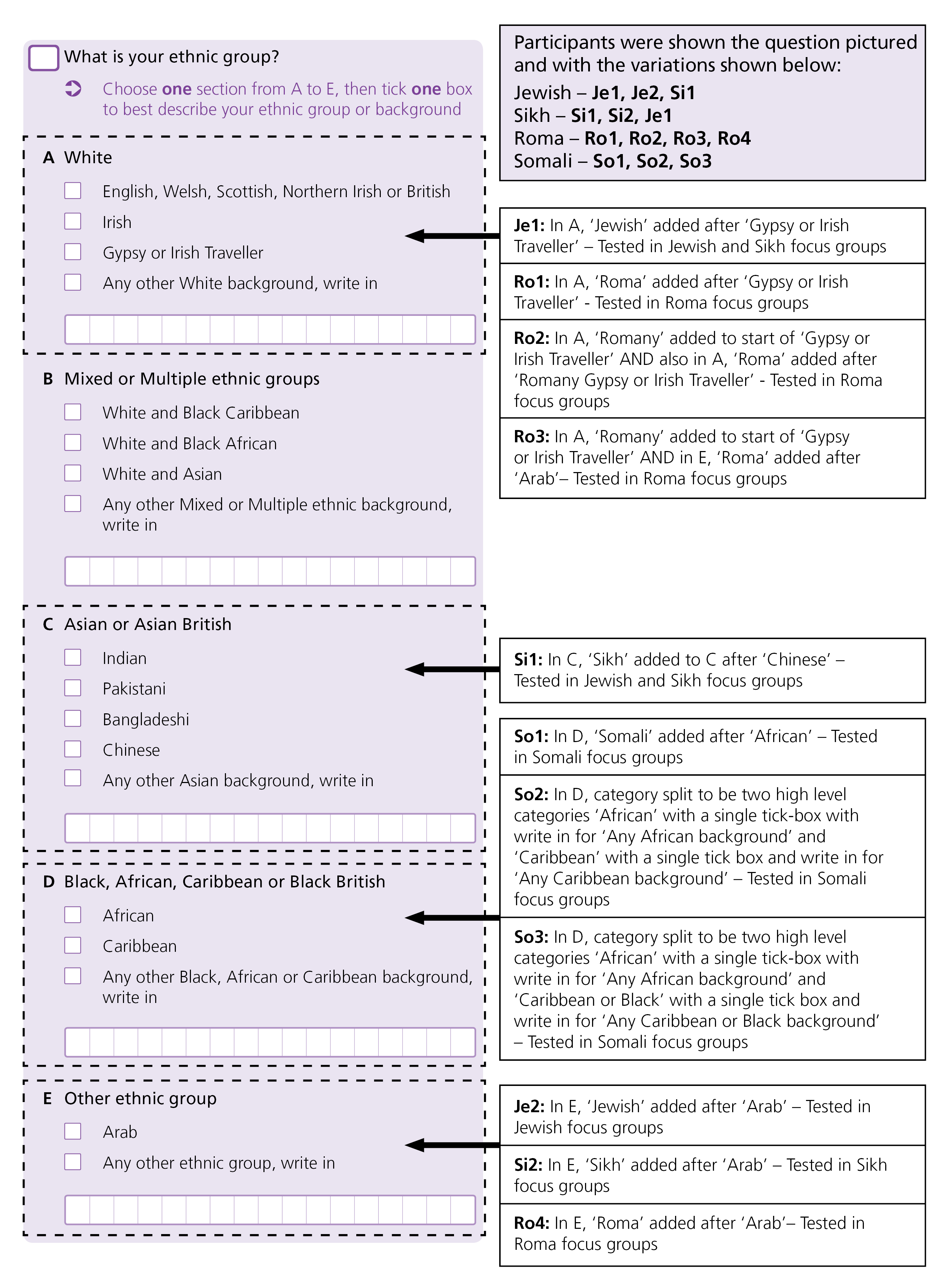

The stakeholder engagement and testing results are discussed below for each group in turn. Figure 4 illustrates the different variations in the design of the ethnic group question that were used in this test.

Stakeholder engagement and correspondence received has not provided evidence that would increase the strength of user need already identified for Somali, Sikh or Jewish. Some evidence provided strengthened the case to add a “Roma” tick-box.

The strength of overall need was assessed using our prioritisation methodology. The strongest case is for data on Roma, followed by Somali, Sikh and Jewish.

Figure 4: Ethnic group question variants tested in qualitative focus groups

Download this image Figure 4: Ethnic group question variants tested in qualitative focus groups

.png (360.7 kB)Roma: Stakeholder engagement

We’ve further engaged with the Roma community to understand the impact of adding a “Roma” tick-box and to further our understanding of the community’s needs. This has resulted in additional confirmation that data on Roma are lacking and that Roma data are of policy interest, particularly in terms of the improvement of local lettings policies. Similarly, there are service delivery and resource allocation interests, centred around a need for Roma data in school place planning, planning housing developments and meeting language requirements. For example, the NHS has highlighted that data available suggest this group experiences considerably worse health, and lower life expectancy, than average.

In addition, further evidence has been evaluated since December 2017 that increases the strength of user need for a “Roma” tick-box. This relates to a need to understand the Roma community’s higher unemployment rates and lower educational outcomes compared with other communities for policy development and equality monitoring.

Within the community there is consistent support for a “Roma” tick-box. Community support networks and volunteers are welcoming of a tick-box and keen to support its use in the 2021 Census. Roma was considered the most appropriate term to use for the Roma community. Gypsy and more specific Roma terminology (such as Rumungre or Sinti) was not considered appropriate or acceptable for the Roma community. Community support officers were willing to support the community through engagement activities to encourage involvement in the 2021 Census.

Roma: Research and testing

The qualitative work included a series of focus groups, details of which can be found in Annex 4: A. Within the Roma focus groups, participants were shown different variations of the ethnicity question (Figure 4), which were:

the 2011 version with slightly updated design to improve readability

“Romany Gypsy or Irish Traveller” tick-box in White and Roma tick-box included in Other

“Romany Gypsy or Irish Traveller” tick-box in White and Roma tick-box included in White

“Roma” included in Other

“Roma” included in White

Terms used to indicate identity are particularly sensitive for the Roma community. Participants felt that the use of the word “Gypsy” was highly offensive to them and they felt that they were being asked to incorrectly identify themselves. Participants were much happier with the addition of a visible “Roma” tick-box, which would give them the option to record their ethnic group correctly. The placement of a “Roma” tick-box under the White high-level category was acceptable, with participants feeling that they should be placed in close proximity to the “Gypsy or Irish Traveller” tick-box.

Roma participants were much less likely to have previously encountered the census, and were less familiar with the ethnic group question than other ethnic groups, due to having migrated relatively recently. Consequently, Roma responses to an ethnic group question without a “Roma” tick-box are wide-ranging. Responses included Romani, different nationalities, and expressing both Roma and a specific national identity together.

Without a “Roma” tick-box, or when a “Roma” tick-box is less prominently visible within the question, participants tended to answer incorrectly, for example choosing the tick-box for “Gypsy or Irish Traveller” and writing in Roma. Participants rationalised that this was where they should respond on the basis that Roma are often referred to as Gypsies. With Roma placed under the Other high-level category, some participants would miss it completely when responding to the question.

A “Roma” tick-box included in the White high-level category was highly visible to respondents, and immediately followed the “Gypsy or Irish Traveller” tick-box. This meant respondents were much more likely to see and use the tick-box even if they did not necessarily identify as White.

The proximity with the “Gypsy and Irish Traveller” tick-box helped to resolve confusion over whether they should identify as Gypsies. Whilst recognising that Gypsies and Roma are not the same, some participants did express an affinity to this other ethnic group and their shared experiences, feeling that it made sense for the two response options to be adjacent.

These conclusions were supported by informal interviews and group discussions that we had previously held with Roma participants (Annex 4: B, 4: D). In these earlier focus groups, participants felt that both the term Roma and a “Roma” tick-box were acceptable and they also expressed discomfort with the term Gypsy. It was explained that they identify strongly as Roma, not Gypsy, but it is commonplace for Roma to be referred to as Gypsies and there are a few who still identify as such.

In the absence of a “Roma” tick-box, Roma participants were uncertain as to which high-level category to respond within. This uncertainty included whether they should write in Roma or a nationality instead, and whether Gypsy or Irish Traveller was intended to apply to them. Roma participants identified with and used the “Roma” tick-box, resolving confusion as to how and where they should respond.

Somali: Stakeholder engagement

We have engaged with the Somali community to understand the impact of adding a “Somali” tick-box, for example acceptability of terminology, and to further our understanding of their needs. Somali community representatives and stakeholders had a strong consensus that better data for the ethnically Somali population is needed because Somalis are experiencing significant disadvantage in several areas of life including employment, housing, health and education.

The engagement also highlighted the large number of ethnic identities currently encapsulated within the current African response option.

No objections to the word Somali were raised and the community representatives would support a tick-box, so long as respondents did not have to choose between an African and a Somali identity. In addition, there was some concern that this could cause suspicion if Somali is the only African ethnicity to have a tick-box.

Somali: Research and testing

Within the Somali and Black African focus groups, participants were shown different variations of the ethnicity question (see Figure 4), which were:

the 2011 version with slightly updated design to improve readability

“Somali” tick-box included in Black, African, Caribbean or Black British

splitting of African and Caribbean with no colour terminology and examples

splitting of African and Caribbean with colour terminology and examples

Focus groups were conducted with Somali and Black African (with no Somali heritage) participants, with both groups being consulted separately about the introduction of a Somali response option.

The addition of the tick-box enabled participants to locate Somali and identify with their chosen identity – this was particularly useful for those participants with lower English literacy levels.

Set against this, the inclusion of a “Somali” tick-box raised suspicions amongst Somali participants with higher literacy levels, and Black African participants, about why Somali was being singled out. This also raised suspicions about fairness and segregation amongst some of the participants. These participants expressed suspicion as to why the data on ethnic Somali respondents were needed, with some commenting that this reflected a history of discrimination against the Somali population.

Some participants expressed pride in identifying with a “Somali” tick-box, commenting that the UK government now recognised Somalis as an important group in England and Wales. This sentiment was not shown by Somali participants with higher literacy levels or who were more politically engaged. The positioning of Somali under the high-level category of African caused confusion for some participants about which response option to choose. Having both a Somali and African identity was important for participants and the inclusion could lead to participants to multi-tick as some felt that choosing between the two identities was too difficult.

Many participants expressed a desire to identify as African as this was an important part of their ethnic identity. Yet participants often felt they were denied this identity by other groups of African heritage who suggested they were “not really African” due to differences of language, hair and religion.

Due to these acceptability issues with adding a “Somali” tick-box, we investigated the best way to achieve a more detailed breakdown of African ethnic groups without adding such a tick-box. During cognitive interviews (see Annex 4: F for further details), participants discussed two approaches, which were:

“African” modified to “African, write in”, with a write-in box specifically for that response option

“African” modified to “African, write in below”, with the respondent directed to the existing write-in box for the “Any other Black, Black British or Caribbean background, write in” response option

With the introduction of “African, write in below” participants were able to provide more information on their African identity.

The design of the new question captured more detail on African identities. We’ll engage with communities to raise awareness of this modification to the question allowing them to express a Somali or other African identity.

Sikh: Stakeholder engagement

We’ve extensively engaged with the Sikh community to understand the impact of adding a “Sikh” tick-box and to further our understanding of their needs. This included discussion of interaction between the religious affiliation and ethnic group questions.

The further engagement led to reiteration of the needs raised during the topic consultation and ethnic group follow-up survey. These provided strong evidence that Sikhs are experiencing significant disadvantage in multiple areas of life, including employment, pay and educational attainment. There is some evidence of need for data on Sikhs for resource allocation and service delivery. However, the examples given often relate to being religiously Sikh, for example applications for free schools and to plan for the development of Gurdwaras and related facilities.

There are differing views within the Sikh population as to whether a specific tick-box should be added to the 2021 Census ethnic group question. The views on each side are passionately held. Discussions conducted with the community do not, therefore, fully support a “Sikh” ethnic group tick-box. However, suggestions have been provided on how Sikh engagement could be maximised, for example, by providing materials in Punjabi and communicating the importance of census data in resource allocation and service planning.

We received information from a survey of Gurdwaras enquiring about acceptance of a “Sikh” ethnic group tick-box, which showed a high acceptance for inclusion. The survey gave us more insight into the views of leaders of Sikh groups, alongside our other research. Independent research was undertaken for us to further understand the acceptability of the Sikh response option within the ethnic group question.

Additionally, the Sikh Federation UK suggested we investigate whether it’s possible to use Sikh names identified in the 2011 Census as a way of expanding our understanding of the Sikh population in England and Wales. The research undertaken focused on those who didn’t respond to the census religion question or who said they had no religion, and attempted to estimate how many of those people might be part of a wider Sikh community. Despite the limitations of this research, it does add further context to the debate around the size of population who might potentially self-identify as Sikh. Based on the assumptions we made, up to a further 20,000 persons from the non-responders to the religion question and up to a further 33,300 persons who recorded having no religion could be added to this group. These estimates represent upper limits, based on the assumptions made. Full details of this research are provided in Annex 5.

Sikh: Research and testing

Within Sikh focus groups, participants were shown different variations of the ethnicity question, which were:

the 2011 version with slightly updated design to improve readability

a “Sikh” tick-box included in the Asian section

a “Sikh” tick-box included in the Other section

a “Jewish” tick-box included in the White section

The focus groups found that whilst respondents did not always fully identify with the response options available, they did not feel burdened by completing the question in the absence of a “Sikh” tick-box. Many were accustomed to completing an ethnic group question, and felt they had sufficient space to self-identify by using the write in option if they did not wish to use the existing tick-boxes.

There’s some evidence that being Sikh is an important part of ethnic identity, but this was observed within a particular demographic (older male participants), rather than being a theme consistent across all participants. The vast majority, however, felt that a “Sikh” tick-box was inappropriate. Many younger participants were more concerned about expressing the British aspect of their ethnic identity, rather than a Sikh element.

The younger participants felt that whilst being Sikh was a core part of their identity, it was not part of their ethnic identity, and to suggest otherwise was viewed as unacceptable and confusing. They considered it unfair that not all other religions were included within the question design and were therefore not given an opportunity to assert their religious identity here, too. They also saw the inclusion as an attempt to segregate them from other aspects of their identity, for example their Asian or Indian heritage.

The addition of a “Sikh” tick-box, and consequent conflict between choosing either Sikh or Indian as a response option, was confusing and burdensome to participants. Both Sikh and Indian heritage were important aspects of their identity and being placed in a position where they had to choose between the two was difficult. Consequently, some respondents were ticking both the “Indian” and “Sikh” tick-boxes, which may lead to lower quality data being outputted due to automated processing counting one response only.

Taking all this into account, our view is that the needs can be met through the following:

continued inclusion of a religion question, with a specific Sikh response option

development of “search-as-you-type” capability which will make it easier to specify as one wishes in the “other” box within the ethnicity topic for those who wish to use it

flexible data outputs which will allow analysis of those who define their religious affiliation as Sikh (through the religion response option) and those who define their ethnic group as Sikh through the use of the “search-as-you-type” capability on the online ethnic group question

increase in the analytical offering and outputs for all ethnic groups

estimation of the Sikh population from all sources to assess the numbers who may declare themselves of Sikh background

utilisation of the Digital Economy Act 2017 to undertake data-linking for research purposes that will ensure that data on the Sikh population is available across public services, not just census-collected data – we will work with Departments across Government to ensure this happens not just for the census but on an ongoing basis

updates to our guidance on harmonisation to ensure that public bodies are fully aware of their duties to record information on the Sikh community

work with members of the Sikh population to encourage wider participation in the census and to raise awareness of the options of writing in their identity in the ethnic group question

development of an online flexible dissemination system where users can specify the data they need and define their own queries to build tables

We have also offered to:

work with local authorities and provide analysis to help them better serve the different religious communities in their areas

work with communities to ensure the data are easily made available to decision-makers and used

Jewish: Stakeholder engagement

We’ve engaged with Jewish community representatives to understand the impact of adding a “Jewish” tick-box and to further our understanding of the community’s needs. They raised concerns around the possibility that inclusion of a “Jewish” ethnic group tick-box could change how respondents react to the religious affiliation question.

This led to reconsideration by stakeholders of the need raised during the topic consultation and ethnic group follow-up survey, as the continuity of the religious affiliation data was of greater importance.

Jewish: Research and testing

Within the Jewish focus groups, participants were shown different variations of the ethnicity question, which were:

the 2011 version with slightly updated design to improve readability

a “Jewish” tick-box included in the White section

a “Jewish” tick-box included in the Other section

a “Sikh” tick-box included in the Asian section

Generally, participants would not tick the box under the ethnic group question. The addition of a “Jewish” tick-box was highly unacceptable and raised concerns about discrimination among participants. The inclusion of a Jewish ethnic group tick-box was perceived as a negative attempt to “single out” the Jewish population and evoked comparisons to World War 2 Germany.

Some participants described personal experiences of anti-Semitism and discrimination, and said they were already reluctant to disclose their Jewish identity in certain social situations. This meant that most participants were uncomfortable with the idea of recording Jewish identity as an ethnicity on an official form.

In terms of issues of quality, testing with the focus groups suggested that adding a “Jewish” tick-box may cause confusion about where respondents should be expressing their Jewish identity. This could result in disparities within the data collection.

Summary

We recognise the need from all four areas and will meet the needs from these in different ways.

Our assessment has evidenced that Roma has the strongest case for an additional tick-box. The stakeholder engagement and correspondence has produced no strengthening of user need for Jewish, Sikh or Somali but there has been some strengthening of an additional user need for a breakdown of the Black African category.

The testing and research work leads us to the same conclusion. Addition of a “Roma” tick-box within the White category is acceptable to the Roma community, and the placement near Gypsy or Irish Traveller means that respondents would easily find it. In contrast, the focus groups for the other groups showed that adding a tick-box would not be acceptable due to singling out specific countries of ancestral origin, or religious backgrounds.

In the 2021 Census the ethnic group question will be broadly similar to that used in 2011. The two main changes recommended are:

include a tick-box for Roma within the White category next to Gypsy or Irish Traveller

include an option for those selecting African within the Black African, Caribbean or Black British category to write in a more specific ethnic background

Online, the question will be split into two stages to reduce respondent burden and, both online and on paper, the readability of the question will be increased by removing slashes between terms.

Online “search-as-you-type” capability will also help to ensure people can tell us how they wish to identify themselves. The ethnic group question has always included a write in option, to allow respondents to self-identify as they wish when a tick-box isn’t available. With the online questionnaire, a comprehensive list of suggestions, including Somali, Sikh and Jewish will be available. Respondents will, however, continue to be able to state identities not listed.

Respondents will also be supported in completing the questionnaire in a variety of languages, including, for example, Polish, Punjabi and Somali. Census engagement activities aiming to promote completion of the questionnaire will also have a focus on people from a wide range of different ethnic groups. For example, we’ll assist Roma organisations to provide support for local communities and to raise awareness of the Roma response option.

We’ll continue to consider how to estimate the Sikh population using alternative data sources. This could allow assessment of the numbers who may declare themselves of Sikh background but not through the religion question.

We’ll increase the analytical offering and outputs for all ethnic groups, through flexible outputs.

More widely, the UK Statistics Authority will strengthen the harmonisation guidance on the collection of data on religion alongside ethnicity data across government.

Nôl i'r tabl cynnwys6. Annex 1: Research methods used in evaluation of topics for the 2021 Census

| Research method | Stage of development | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative research methods | ||

| Focus groups | Generating ideas Evaluating respondent understanding and acceptability | Several respondents are brought together to discuss a research topic as a group under the direction of a moderator. Focus groups provide an opportunity for direct and explicit discussion, often used to highlight the research issue. |

| Informal interviews and group discussions at community events | Generating ideas Evaluating respondent understanding and acceptability | The process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic location, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting their well-being. Usually short, informal, qualitative interviews held at community events to gather views and opinions on a topic (for example, the wording of census questions and response options) often relevant to the people in attendance at the event. |

| Cognitive interviews | Evaluating respondent understanding and acceptability | A form of in-depth interviewing with a small number of respondents with explicit attention paid to the mental processes respondents use when answering survey questions. This helps us identify if there are any problems with a question or question design and gain an insight into the source of any difficulty experienced by respondents. |

| Quantitative research methods | ||